The Book of American Negro Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the De Grummond Collection Sarah J

SLIS Connecting Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 9 2013 A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection Sarah J. Heidelberg Follow this and additional works at: http://aquila.usm.edu/slisconnecting Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Heidelberg, Sarah J. (2013) "A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection," SLIS Connecting: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 9. DOI: 10.18785/slis.0201.09 Available at: http://aquila.usm.edu/slisconnecting/vol2/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in SLIS Connecting by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Collection Analysis of the African‐American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection By Sarah J. Heidelberg Master’s Research Project, November 2010 Performance poetry is part of the new black poetry. Readers: Dr. M.J. Norton This includes spoken word and slam. It has been said Dr. Teresa S. Welsh that the introduction of slam poetry to children can “salvage” an almost broken “relationship with poetry” (Boudreau, 2009, 1). This is because slam Introduction poetry makes a poets’ art more palatable for the Poetry is beneficial for both children and adults; senses and draws people to poetry (Jones, 2003, 17). however, many believe it offers more benefit to Even if the poetry that is spoken at these slams is children (Vardell, 2006, 36). The reading of poetry sometimes not as developed or polished as it would correlates with literacy attainment (Maynard, 2005; be hoped (Jones, 2003, 23). -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study. -

RIVERFRONT CIRCULATING MATERIALS (Can Be Checked Out)

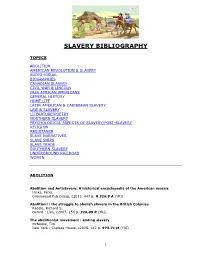

SLAVERY BIBLIOGRAPHY TOPICS ABOLITION AMERICAN REVOLUTION & SLAVERY AUDIO-VISUAL BIOGRAPHIES CANADIAN SLAVERY CIVIL WAR & LINCOLN FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS GENERAL HISTORY HOME LIFE LATIN AMERICAN & CARIBBEAN SLAVERY LAW & SLAVERY LITERATURE/POETRY NORTHERN SLAVERY PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF SLAVERY/POST-SLAVERY RELIGION RESISTANCE SLAVE NARRATIVES SLAVE SHIPS SLAVE TRADE SOUTHERN SLAVERY UNDERGROUND RAILROAD WOMEN ABOLITION Abolition and Antislavery: A historical encyclopedia of the American mosaic Hinks, Peter. Greenwood Pub Group, c2015. 447 p. R 326.8 A (YRI) Abolition! : the struggle to abolish slavery in the British Colonies Reddie, Richard S. Oxford : Lion, c2007. 254 p. 326.09 R (YRI) The abolitionist movement : ending slavery McNeese, Tim. New York : Chelsea House, c2008. 142 p. 973.71 M (YRI) 1 The abolitionist legacy: from Reconstruction to the NAACP McPherson, James M. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, c1975. 438 p. 322.44 M (YRI) All on fire : William Lloyd Garrison and the abolition of slavery Mayer, Henry, 1941- New York : St. Martin's Press, c1998. 707 p. B GARRISON (YWI) Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the heroic campaign to end slavery Metaxas, Eric New York, NY : Harper, c2007. 281p. B WILBERFORCE (YRI, YWI) American to the backbone : the life of James W.C. Pennington, the fugitive slave who became one of the first black abolitionists Webber, Christopher. New York : Pegasus Books, c2011. 493 p. B PENNINGTON (YRI) The Amistad slave revolt and American abolition. Zeinert, Karen. North Haven, CT : Linnet Books, c1997. 101p. 326.09 Z (YRI, YWI) Angelina Grimke : voice of abolition. Todras, Ellen H., 1947- North Haven, Conn. : Linnet Books, c1999. 178p. YA B GRIMKE (YWI) The antislavery movement Rogers, James T. -

Catalogue 143 ~ Holiday 2008 Contents

Between the Covers - Rare Books, Inc. 112 Nicholson Rd (856) 456-8008 will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept Visa, MasterCard, American Express, Discover, and Gloucester City NJ 08030 Fax (856) 456-7675 PayPal. www.betweenthecovers.com [email protected] Domestic orders please include $5.00 postage for the first item, $2.00 for each item thereafter. Images are not to scale. All books are returnable within ten days if returned in Overseas orders will be sent airmail at cost (unless other arrange- the same condition as sent. Books may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. ments are requested). All items insured. NJ residents please add 7% sales tax. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany order if you are Members ABAA, ILAB. unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions Cover verse and design by Tom Bloom © 2008 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. Catalogue 143 ~ Holiday 2008 Contents: ................................................................Page Literature (General Fiction & Non-Fiction) ...........................1 Baseball ................................................................................72 African-Americana ...............................................................55 Photography & Illustration ..................................................75 Children’s Books ..................................................................59 Music ...................................................................................80 -

Black Women in Massachusetts, 1700-1783

2014 Felicia Y. Thomas ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ENTANGLED WITH THE YOKE OF BONDAGE: BLACK WOMEN IN MASSACHUSETTS, 1700-1783 By FELICIA Y. THOMAS A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Deborah Gray White and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Entangled With the Yoke of Bondage: Black Women in Massachusetts, 1700-1783 By FELICIA Y. THOMAS Dissertation Director: Deborah Gray White This dissertation expands our knowledge of four significant dimensions of black women’s experiences in eighteenth century New England: work, relationships, literacy and religion. This study contributes, then, to a deeper understanding of the kinds of work black women performed as well as their value, contributions, and skill as servile laborers; how black women created and maintained human ties within the context of multifaceted oppression, whether they married and had children, or not; how black women acquired the tools of literacy, which provided a basis for engagement with an interracial, international public sphere; and how black women’s access to and appropriation of Christianity bolstered their efforts to resist slavery’s dehumanizing effects. While enslaved females endured a common experience of race oppression with black men, gender oppression with white women, and class oppression with other compulsory workers, black women’s experiences were distinguished by the impact of the triple burden of gender, race, and class. This dissertation, while centered on the experience of black women, considers how their experience converges with and diverges from that of white women, black men, and other servile laborers. -

Remembering Slavery in Massachusetts

Margot Minardi. Making Slavery History: Abolitionism and the Politics of Memory in Massachusetts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. 240 pp. $49.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-19-537937-2. Reviewed by Jeff Fortney Published on H-CivWar (March, 2012) Commissioned by Hugh F. Dubrulle (Saint Anselm College) According to Margot Minardi in Making Slav‐ Historical narratives written by Jeremy Belk‐ ery History, the history of the American Revolu‐ nap and other early historians in the wake of the tion taught in classrooms for generations, com‐ Revolution emphasized the extent to which aboli‐ plete with a runaway slave as frst martyr and an tionism based on “popular sentiment” ended slav‐ African poet as international celebrity, “owes as ery in Massachusetts--while ignoring the large much to Massachusetts activists and historians in number of “Bay Staters (who) did not share his the nineteenth century as it does to Crispus At‐ [Belknap’s] antislavery views” (p. 20). Further tucks or Phillis Wheatley themselves” (p. 12). Mi‐ complicating this issue were accounts of census nardi embraces the framework of historical mem‐ takers instructed to conduct their counts in such a ory to revisit “the fundamental question of recent way that slaves would not be recorded in the 1790 social history--‘who makes history?’”--including census. Moreover, a law passed in 1788 banning who disappeared, who reappeared, and what this “African or negro” people from living in Massa‐ meant for understanding ideology and identity in chusetts undermined the historical concept of lib‐ Massachusetts (p. 11). Over the course of fve erty for all races espoused in Belknap’s historical chapters, Minardi investigates stories about slaves narrative (p. -

William Cooper Nell. the Colored Patriots of the American Revolution

William Cooper Nell. The Colored Patriots of the American ... http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/nell/nell.html About | Collections | Authors | Titles | Subjects | Geographic | K-12 | Facebook | Buy DocSouth Books The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, With Sketches of Several Distinguished Colored Persons: To Which Is Added a Brief Survey of the Condition And Prospects of Colored Americans: Electronic Edition. Nell, William Cooper Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities supported the electronic publication of this title. Text scanned (OCR) by Fiona Mills and Sarah Reuning Images scanned by Fiona Mills and Sarah Reuning Text encoded by Carlene Hempel and Natalia Smith First edition, 1999 ca. 800K Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1999. © This work is the property of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It may be used freely by individuals for research, teaching and personal use as long as this statement of availability is included in the text. Call number E 269 N3 N4 (Winston-Salem State University) The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH digitization project, Documenting the American South. All footnotes are moved to the end of paragraphs in which the reference occurs. Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as entity references. All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and " respectively. All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively. -

Slave Advertising in the Colonial Newspaper: Mirror to the Dilemma

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 285 152 CS 210 475 AUTHOR Bradley, Patricia TITLE Slave Advertising in the Colonial Newspaper: Mirror to the Dilemma. PUB DATE Aug 87 NOTE 52p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (70th, San Antonio, TX, August 1-4, 1987). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) -- Information Analyses (070) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Advertising; Black Culture; Black History; *Colonial History (United States); *Cultural Context; Media Research; Minority Groups; *Newspapers; Racial Discrimination; Regional Attitudes; *Slavery; Social Differences; Social History IDENTIFIERS *Advertisements; Editorial Policy; *Journalism History ABSTRACT To explore racial attitudes from the colonial period of the United States, a study examined advertising practices regarding announcements dealing with black slaves in colonial newspapers in Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryllnd, Virginia, and South Carolina. Careful scrutiny revealed no relationship between the editorial stance of a newspaper and the amount of slave advertising the newspaper carried. Overall the ads suggest that the northeast attitude toward slavery was that it was a not necessarily permanent status necessary to a functioning society rather than a condition based on racist assumptions or inherent deficiencies of the black race. Examination of ads showed that slave advertising fell into two categories: slaves for sale and runaways with regional characteristics. Findings also showed that sale advertisements emphasized the skillfulness of the individual slave rather than a passive, dependent personality, while runaway ads were couched in negative terms--that is, the slave was given to alcohol abuse, or considered artful and deceitful for having run away. -

Cherished Possessions: a New England Legacy. Educator's Resource Guide

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 481 926 SO 035 405 AUTHOR Peters, Amy L. TITLE Cherished Possessions: A New England Legacy. Educator's Resource Guide. PUB DATE 2003-00-00 NOTE 73p.; A Traveling Exhibition from the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities. Prepared by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA) (Boston, Massachusetts) . Color images may not reproduce adequately. AVAILABLE FROM Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 141 Cambridge Street, Boston, MA 02114. Tel: 617-227-3956; Web site: http://www.spnea.org/. For full text: http://www.spnea.org/ schoolprograms/educatorsresource.htm. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Art Education; *Design Crafts; Elementary Secondary Education; *Exhibits; *Fine Arts; *Geographic Regions; Heritage Education; Instructional Materials; Material Culture; Primary Sources; Resource Materials; Social Studies; Thematic Approach; United States History IDENTIFIERS Antiques; *Artifacts; *New England ABSTRACT The exhibition, "Cherished Possessions: A New England Legacy," consists of approximately 200 objects drawn from the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities collection of fine and decorative arts. Each item in the exhibition has been selected for its ability to tell a story and to place the history of that item within the larger history of the region and the nation. This educator's resource guide is designed to help teachers make the most of a visit to the exhibition. The guide allows teachers to focus on specific themes within the exhibition that relate to their classroom teaching. Five thematic sections give students a view of different time periods in U.S. -

Exploration of Black Voices in Literature

Exploration of Black Voices in Literature -Twinsburg High School proposal for elective course beginning 21-22 school year- Daneé Pinckney Table of Contents Course Description…………………………………………………………………………….....4 Essential Questions……………………………………………………………………………....5 Units of Coverage Unit 1: Early African Kingdoms and Atlantic Slave Trade…………………………...6 Unit 2: Slavery in the United States Unit 3: Civil War and Reconstruction Unit 4: The Rise and Fight of the Black Middle Class Unit 5: Contemporary Issue of Blacks in America Grammar…………………………………………………………………………………………..8 Additional Notes…………………………………………………………………………………..9 Course Description This is an elective literature course examining the history and culture of African Americans in the United States beginning with early African literary tradition and onward through the modern African-American experience in an interdisciplinary design. The course addresses the literary and artistic contributions of early Africans and African-Americans to American culture. Students will recognize the range and variety of the writing of African-Americans throughout history and into contemporary literature and will be able to identify the ways that this literature responds to historical and social events. Through close consideration of verbal and literary modes, including, but not limited to: African retentions, oral traditions, signifying, folklore, and music, the course will explore the creation of the unique African American literary voice, and how it has affected both African Americans’ understandings of themselves, as well as the ways in which they have historically been understood in the American popular imagination. In an effort to critically map the genealogies of this tradition we will be interrogating not only the historical and political contexts of the works, but also the ways in which issues of gender, sexuality, and class specifically inform the works. -

Frontpiece, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral by Phillis Wheatley, 1773 PRIMARY SOURCE

Museum of the American Revolution Frontpiece, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral by Phillis Wheatley, 1773 PRIMARY SOURCE PHOTOGRAPH Frontpiece, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral by Phillis Wheatley, 1773 Featuring Portrait of Phillis Wheatley, attributed to Scipio Moorhead Museum of the American Revolution In 1753, at the age of 7 or 8, a young girl was kidnapped from the Senegambia region of West Africa (now The Gambia and Senegal) and shipped to Boston, Massachusetts. Renamed Phillis, after the name of the ship that carried her, she was purchased by a Boston tailor named John Wheatley as a present for his wife, Susanna. They gave her their last name. In keeping with their religious beliefs, the Wheatleys taught her to read and write English, and – after noticing her creative and intellectual abilities – encouraged her in her writing of poetry, even sending her work to local newspapers. In the 1770s, they began seeking a publisher to print a book of her poems. However, many people did not believe that an enslaved person, or a person of African descent in general, was intelligent enough or creative enough to actually write poetry. Wheatley had to convince a dozen of Boston’s most prominent men that she had truly written the poems, but even with a letter of support written by them, Boston publishers refused to print it. Wheatley was taken to London by her owner’s son Nathaniel, where a publisher agreed to work with them. Wheatley became the first African woman in North America to be a published author. Somehow, by the time Wheatley returned to Boston, the Wheatleys had been convinced to free her.