Disputation, Poetry, Slavery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti-Semitism: a History

ANTI-SEMITISM: A HISTORY 1 www.counterextremism.com | @FightExtremism ANTI-SEMITISM: A HISTORY Key Points Historic anti-Semitism has primarily been a response to exaggerated fears of Jewish power and influence manipulating key events. Anti-Semitic passages and decrees in early Christianity and Islam informed centuries of Jewish persecution. Historic professional, societal, and political restrictions on Jews helped give rise to some of the most enduring conspiracies about Jewish influence. 2 Table of Contents Religion and Anti-Semitism .................................................................................................... 5 The Origins and Inspirations of Christian Anti-Semitism ................................................. 6 The Origins and Inspirations of Islamic Anti-Semitism .................................................. 11 Anti-Semitism Throughout History ...................................................................................... 17 First Century through Eleventh Century: Rome and the Rise of Christianity ................. 18 Sixth Century through Eighth Century: The Khazars and the Birth of an Enduring Conspiracy Theory AttacKing Jewish Identity ................................................................. 19 Tenth Century through Twelfth Century: Continued Conquests and the Crusades ...... 20 Twelfth Century: Proliferation of the Blood Libel, Increasing Restrictions, the Talmud on Trial .............................................................................................................................. -

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution ROBERT J. TAYLOR J. HI s YEAR marks tbe 200tb anniversary of tbe Massacbu- setts Constitution, the oldest written organic law still in oper- ation anywhere in the world; and, despite its 113 amendments, its basic structure is largely intact. The constitution of the Commonwealth is, of course, more tban just long-lived. It in- fluenced the efforts at constitution-making of otber states, usu- ally on their second try, and it contributed to tbe shaping of tbe United States Constitution. Tbe Massachusetts experience was important in two major respects. It was decided tbat an organic law should have tbe approval of two-tbirds of tbe state's free male inbabitants twenty-one years old and older; and tbat it sbould be drafted by a convention specially called and chosen for tbat sole purpose. To use the words of a scholar as far back as 1914, Massachusetts gave us 'the fully developed convention.'^ Some of tbe provisions of the resulting constitu- tion were original, but tbe framers borrowed heavily as well. Altbough a number of historians have written at length about this constitution, notably Prof. Samuel Eliot Morison in sev- eral essays, none bas discussed its construction in detail.^ This paper in a slightly different form was read at the annual meeting of the American Antiquarian Society on October IS, 1980. ' Andrew C. McLaughlin, 'American History and American Democracy,' American Historical Review 20(January 1915):26*-65. 2 'The Struggle over the Adoption of the Constitution of Massachusetts, 1780," Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 50 ( 1916-17 ) : 353-4 W; A History of the Constitution of Massachusetts (Boston, 1917); 'The Formation of the Massachusetts Constitution,' Massachusetts Law Quarterly 40(December 1955):1-17. -

February 2021 L. KINVIN WROTH Résumé PRESENT POSITION

February 2021 L. KINVIN WROTH Résumé PRESENT POSITION Professor of Law Emeritus, 2017-date, Vermont Law School. 164 Chelsea Street, P.O. Box 96 South Royalton, Vermont 05068 Telephone: 802-831-1268. Fax: 802-831-1408 E-mail: [email protected] OTHER POSITIONS HELD Professor of Law, 1996-2017, Vermont Law School President, 2003-2004, and Dean, 1996-2004, Vermont Law School Professor of Law, University of Maine School of Law, 1966-1996 Dean, University of Maine School of Law, 1980-1990. Acting Dean, University of Maine School of Law, 1978-80. Associate Dean, University of Maine School of Law, 1977-78. Research Fellow, Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History, Harvard University, 1968-74 (concurrent with Maine appointment). Associate Professor of Law, University of Maine School of Law, 1964-66. Research Associate, Harvard Law School, 1962-64. Teaching Fellow/Assistant Professor of Law, Dickinson School of Law, 1960-62. Active duty, Lieutenant, USAF, 1954-57 (Intelligence Officer). PLACE AND DATE OF BIRTH Providence, Rhode Island, July 9, 1932 EDUCATION Moses Brown School, Providence, R.I., 1950 B.A., Yale, 1954 LL.B. (J.D.), Harvard, 1960 PUBLICATIONS Books: Coeditor, with Hiller B. Zobel, Legal Papers of John Adams, 3 vols., Harvard, 1965; paper, Atheneum, 1968; and on line at http://www.masshist.org/ff/browseVol.php?series=lja&vol=1, …vol=2,… vol=3. Coauthor, with Richard H. Field and Vincent L. McKusick, Maine Civil Practice, 2d edition, 2 vols., West, 1970, and 1972, 1974, 1977, and 1981 Supplements (with Charles A. Harvey, Jr., and Raymond G. McGuire). -

Three Lawyer-Poets of the Nineteenth Century

Three Lawyer-Poets of the Nineteenth Century M.H. Hoeflich Lawrence Jenab N TODAY’S POPULAR IMAGINATION, law- many of the most prominent American law- yers are a stolid group, with little imagi- yers also practiced the art of versification. nation or love of literature. Poets, on the That many antebellum American lawyers other hand, must all be like Dylan Thomas fancied themselves poets is not at all surpris- Ior Sylvia Plath, colorful and often tortured ing. Indeed, when one considers the history souls, living life to the fullest in the bohe- of the legal profession in England, Europe, mian quarters of Paris or New York City, not and the United States, one quickly discov- the drab canyons of Wall Street. When we ers that lawyers were often of a poetic turn. think of nineteenth-century poets, we tend Petrarch, one of the first Italian Renaissance to think of the omnivorous Walt Whitman, poets, was trained as a lawyer. In the early the romantic Lord Byron, or the sentimental eighteenth century, young lawyers used a Emily Dickinson. When we think of nine- collection of Coke’s Reports set in two-line teenth-century lawyers, however, we think couplets as an aide-memoire.² Later, some of of staid Rufus Choate or rustic Abe Lincoln. eighteenth-century England’s best-known Few of us can imagine a time or place in lawyers and jurists were also famed as poets. which lawyers were poets and poets lawyers, Sir William Blackstone’s first calling was not let alone when men could achieve fame as to the law but to poetry; his most famous both. -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

Lemuel Shaw, Chief Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court Of

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com AT 15' Fl LEMUEL SHAW I EMUEL SHAW CHIFF jl STIC h OF THE SUPREME Jli>I«'RL <.OlRT OF MAS Wlf .SfcTTb i a 30- 1 {'('• o BY FREDERIC HATHAWAY tHASH BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY 1 9 1 8 LEMUEL SHAW CHIEF JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME JUDICIAL COURT OF MASSACHUSETTS 1830-1860 BY FREDERIC HATHAWAY CHASE BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY (Sbe Slibttfibe $rrtf Cambribgc 1918 COPYRIGHT, I9lS, BY FREDERIC HATHAWAY CHASE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Published March iqiS 279304 PREFACE It is doubtful if the country has ever seen a more brilliant group of lawyers than was found in Boston during the first half of the last century. None but a man of grand proportions could have emerged into prominence to stand with them. Webster, Choate, Story, Benjamin R. Curtis, Jeremiah Mason, the Hoars, Dana, Otis, and Caleb Cushing were among them. Of the lives and careers of all of these, full and adequate records have been written. But of him who was first their associate, and later their judge, the greatest legal figure of them all, only meagre accounts survive. It is in the hope of sup plying this deficiency, to some extent, that the following pages are presented. It may be thought that too great space has been given to a description of Shaw's forbears and early surroundings; but it is suggested that much in his character and later life is thus explained. -

RIVERFRONT CIRCULATING MATERIALS (Can Be Checked Out)

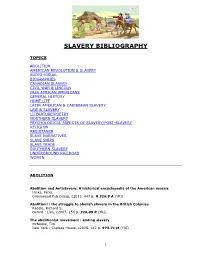

SLAVERY BIBLIOGRAPHY TOPICS ABOLITION AMERICAN REVOLUTION & SLAVERY AUDIO-VISUAL BIOGRAPHIES CANADIAN SLAVERY CIVIL WAR & LINCOLN FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS GENERAL HISTORY HOME LIFE LATIN AMERICAN & CARIBBEAN SLAVERY LAW & SLAVERY LITERATURE/POETRY NORTHERN SLAVERY PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF SLAVERY/POST-SLAVERY RELIGION RESISTANCE SLAVE NARRATIVES SLAVE SHIPS SLAVE TRADE SOUTHERN SLAVERY UNDERGROUND RAILROAD WOMEN ABOLITION Abolition and Antislavery: A historical encyclopedia of the American mosaic Hinks, Peter. Greenwood Pub Group, c2015. 447 p. R 326.8 A (YRI) Abolition! : the struggle to abolish slavery in the British Colonies Reddie, Richard S. Oxford : Lion, c2007. 254 p. 326.09 R (YRI) The abolitionist movement : ending slavery McNeese, Tim. New York : Chelsea House, c2008. 142 p. 973.71 M (YRI) 1 The abolitionist legacy: from Reconstruction to the NAACP McPherson, James M. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, c1975. 438 p. 322.44 M (YRI) All on fire : William Lloyd Garrison and the abolition of slavery Mayer, Henry, 1941- New York : St. Martin's Press, c1998. 707 p. B GARRISON (YWI) Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the heroic campaign to end slavery Metaxas, Eric New York, NY : Harper, c2007. 281p. B WILBERFORCE (YRI, YWI) American to the backbone : the life of James W.C. Pennington, the fugitive slave who became one of the first black abolitionists Webber, Christopher. New York : Pegasus Books, c2011. 493 p. B PENNINGTON (YRI) The Amistad slave revolt and American abolition. Zeinert, Karen. North Haven, CT : Linnet Books, c1997. 101p. 326.09 Z (YRI, YWI) Angelina Grimke : voice of abolition. Todras, Ellen H., 1947- North Haven, Conn. : Linnet Books, c1999. 178p. YA B GRIMKE (YWI) The antislavery movement Rogers, James T. -

The Idea of Medieval Heresy in Early Modern France

The Idea of Medieval Heresy in Early Modern France Bethany Hume PhD University of York History September 2019 2 Abstract This thesis responds to the historiographical focus on the trope of the Albigensians and Waldensians within sixteenth-century confessional polemic. It supports a shift away from the consideration of medieval heresy in early modern historical writing merely as literary topoi of the French Wars of Religion. Instead, it argues for a more detailed examination of the medieval heretical and inquisitorial sources used within seventeenth-century French intellectual culture and religious polemic. It does this by examining the context of the Doat Commission (1663-1670), which transcribed a collection of inquisition registers from Languedoc, 1235-44. Jean de Doat (c.1600-1683), President of the Chambre des Comptes of the parlement of Pau from 1646, was charged by royal commission to the south of France to copy documents of interest to the Crown. This thesis aims to explore the Doat Commission within the wider context of ideas on medieval heresy in seventeenth-century France. The periodization “medieval” is extremely broad and incorporates many forms of heresy throughout Europe. As such, the scope of this thesis surveys how thirteenth-century heretics, namely the Albigensians and Waldensians, were portrayed in historical narrative in the 1600s. The field of study that this thesis hopes to contribute to includes the growth of historical interest in medieval heresy and its repression, and the search for original sources by seventeenth-century savants. By exploring the ideas of medieval heresy espoused by different intellectual networks it becomes clear that early modern European thought on medieval heresy informed antiquarianism, historical writing, and ideas of justice and persecution, as well as shaping confessional identity. -

The Manifesto of the Reformation — Luther Vs. Erasmus on Free Will

203 The Manifesto of the Reformation — Luther vs. Erasmus on Free Will Lee Gatiss The clash between Martin Luther and Desiderius Erasmus over the issue of free will is ‘one of the most famous exchanges in western intellectual history’. 1 In this article, we will examine the background to the quarrel between these two professors, and two of the central themes of Luther’s response to Erasmus—the clarity of Scripture and the bondage of the will. In doing so it is critical to be aware that studying these things ‘operates as a kind of litmus test for what one is going to become theologically’. 2 Ignoring the contemporary relevance and implications of these crucially important topics will not be possible; whether thinking about our approach to the modern reformation of the church, our evangelism, pastoral care, or interpretation of the Bible there is so much of value and vital importance that it would be a travesty to discuss them without at least a nod in the direction of the twenty-first century church. From Luther’s perspective, as Gerhard Forde rightly says, this was not just one more theological debate but ‘a desperate call to get the gospel preached’. 3 This is a fundamentally significant dispute historically since it involved key players in the two major movements of the sixteenth century: Erasmus the great renaissance humanist and Luther the Reformation Hercules. 4 The debate between these two titans reveals not only the reasons behind ‘humanism’s programmatic repudiation of the Reformation’ 5 but also a clear view of the heartbeat of the Reformation itself since, as B. -

Catalogue 143 ~ Holiday 2008 Contents

Between the Covers - Rare Books, Inc. 112 Nicholson Rd (856) 456-8008 will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept Visa, MasterCard, American Express, Discover, and Gloucester City NJ 08030 Fax (856) 456-7675 PayPal. www.betweenthecovers.com [email protected] Domestic orders please include $5.00 postage for the first item, $2.00 for each item thereafter. Images are not to scale. All books are returnable within ten days if returned in Overseas orders will be sent airmail at cost (unless other arrange- the same condition as sent. Books may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. ments are requested). All items insured. NJ residents please add 7% sales tax. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany order if you are Members ABAA, ILAB. unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions Cover verse and design by Tom Bloom © 2008 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. Catalogue 143 ~ Holiday 2008 Contents: ................................................................Page Literature (General Fiction & Non-Fiction) ...........................1 Baseball ................................................................................72 African-Americana ...............................................................55 Photography & Illustration ..................................................75 Children’s Books ..................................................................59 Music ...................................................................................80 -

Black Women in Massachusetts, 1700-1783

2014 Felicia Y. Thomas ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ENTANGLED WITH THE YOKE OF BONDAGE: BLACK WOMEN IN MASSACHUSETTS, 1700-1783 By FELICIA Y. THOMAS A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Deborah Gray White and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Entangled With the Yoke of Bondage: Black Women in Massachusetts, 1700-1783 By FELICIA Y. THOMAS Dissertation Director: Deborah Gray White This dissertation expands our knowledge of four significant dimensions of black women’s experiences in eighteenth century New England: work, relationships, literacy and religion. This study contributes, then, to a deeper understanding of the kinds of work black women performed as well as their value, contributions, and skill as servile laborers; how black women created and maintained human ties within the context of multifaceted oppression, whether they married and had children, or not; how black women acquired the tools of literacy, which provided a basis for engagement with an interracial, international public sphere; and how black women’s access to and appropriation of Christianity bolstered their efforts to resist slavery’s dehumanizing effects. While enslaved females endured a common experience of race oppression with black men, gender oppression with white women, and class oppression with other compulsory workers, black women’s experiences were distinguished by the impact of the triple burden of gender, race, and class. This dissertation, while centered on the experience of black women, considers how their experience converges with and diverges from that of white women, black men, and other servile laborers. -

Remembering Slavery in Massachusetts

Margot Minardi. Making Slavery History: Abolitionism and the Politics of Memory in Massachusetts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. 240 pp. $49.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-19-537937-2. Reviewed by Jeff Fortney Published on H-CivWar (March, 2012) Commissioned by Hugh F. Dubrulle (Saint Anselm College) According to Margot Minardi in Making Slav‐ Historical narratives written by Jeremy Belk‐ ery History, the history of the American Revolu‐ nap and other early historians in the wake of the tion taught in classrooms for generations, com‐ Revolution emphasized the extent to which aboli‐ plete with a runaway slave as frst martyr and an tionism based on “popular sentiment” ended slav‐ African poet as international celebrity, “owes as ery in Massachusetts--while ignoring the large much to Massachusetts activists and historians in number of “Bay Staters (who) did not share his the nineteenth century as it does to Crispus At‐ [Belknap’s] antislavery views” (p. 20). Further tucks or Phillis Wheatley themselves” (p. 12). Mi‐ complicating this issue were accounts of census nardi embraces the framework of historical mem‐ takers instructed to conduct their counts in such a ory to revisit “the fundamental question of recent way that slaves would not be recorded in the 1790 social history--‘who makes history?’”--including census. Moreover, a law passed in 1788 banning who disappeared, who reappeared, and what this “African or negro” people from living in Massa‐ meant for understanding ideology and identity in chusetts undermined the historical concept of lib‐ Massachusetts (p. 11). Over the course of fve erty for all races espoused in Belknap’s historical chapters, Minardi investigates stories about slaves narrative (p.