Optical and Mechanical Properties of Highly Transparent Glass-Flake Composites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

Molecular Materials for Nonlinear Optics

RICHARD S. POTEMBER, ROBERT C. HOFFMAN, KAREN A. STETYICK, ROBERT A. MURPHY, and KENNETH R. SPECK MOLECULAR MATERIALS FOR NONLINEAR OPTICS An overview of our recent advances in the investigation of molecular materials for nonlinear optical applications is presented. Applications of these materials include optically bistable devices, optical limiters, and harmonic generators. INTRODUCTION of potentially important optical qualities and capabilities Organic molecular materials are a class of materials such as optical bistability, optical threshold switching, in which the organic molecules retain their geometry and photoconductivity, harmonic generation, optical para physical properties when crystallization takes place. metric oscillation, and electro-optic modulation. A sam Changes occur in the physical properties of individual ple of various applications for several optical materials molecules during crystallization, but they are small com is shown in Table 1. pared with those that occur in ionic or metallic solids. The optical effects so far observed in many organic The energies binding the individual molecules together materials result from the interaction of light with bulk in organic solids are also relatively small, making organic materials such as solutions, single crystals, polycrystal molecular solids mere aggregations of molecules held to line fIlms, and amorphous compositions. In these materi gether by weak intermolecular (van der Waals) forces . als, each molecule in the solid responds identically, so The crystalline structure of most organic molecular solids that the response of the bulk material is the sum of the is more complex than that of most metals or inorganic responses of the individual molecules. That effect sug solids; 1 the asymmetry of most organic molecules makes gests that it may be possible to store and process optical the intermolecular forces highly anisotropic. -

2 Types of Noncrystalline Polymers

2 Types of Noncrystalline Polymers 1. Glassy polymer highly interpenetrated/entangled 2. Rubbery polymers random Gaussian coils Glass Transition Temperature εij Two viewpoints: • Increasing T: When kT > magnitude of εij, the thermal fluctuations can overcome local intermolecular bonds and the frozen (“glassy”) structure becomes “fluid-like”. • Decreasing T: As the temperature is lowered and T approaches Tg, the viscosity increases to ∞ and the material becomes “solid” Free Volume Theory of Tg Free volume, VF – extra space beyond what is present in an ordered crystalline packing (beyond the interstitial volume). VF(T) ≡ V(T) – V0(T) • V0 is occupied specific volume of atoms or molecules in the xline state and the spaces between them: ~ VXL. V(T) α • VF increases as T increases due to the Rate of cooling l difference in the thermal expansion V (T) αg XL coefficients (αg vs αl). FAST SLOW • V0(T) ≈ VXL(T) ↔ can take αg ≈αXL dV •V(T) = V (T ) + (T-T ) F T > T F F g g dT g Tg T • define fractional free volume, fF:Vf/V fF(T) = fF(Tg) + (T-Tg)αf αf = αl – αg Viewpoint: Tg occurs when available free volume drops below critical threshold for structural rearrangement [VITRIFICATION POINT], structure “jams up”. Tg Values of Amorphous Materials Table of representative amorphous solids, their bonding types, and their glass transition temperatures removed due to copyright restrictions. See Table 2.2 in Allen, S. M., and E.L. Thomas. The Structure of Materials. New York, NY: J. Wiley & Sons, 1999. Tg for Selected Polymers Glass Transition Temperature -

Characteristics of Thermosetting Polymer Nanocomposites: Siloxane-Imide-Containing Benzoxazine with Silsesquioxane Epoxy Resins

polymers Communication Characteristics of Thermosetting Polymer Nanocomposites: Siloxane-Imide-Containing Benzoxazine with Silsesquioxane Epoxy Resins Chih-Hao Lin 1 , Wen-Bin Chen 2, Wha-Tzong Whang 1 and Chun-Hua Chen 1,* 1 Department of Materials Science and Engineering, National Chiao Tung University, Hsinchu 300093, Taiwan; [email protected] (C.-H.L.); [email protected] (W.-T.W.) 2 Material and Chemical Research Laboratories, Industrial Technology Research Institute, Chutung, Hsinchu 31040, Taiwan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +886-3513-1287 Received: 16 September 2020; Accepted: 26 October 2020; Published: 28 October 2020 Abstract: A series of innovative thermosetting polymer nanocomposites comprising of polysiloxane-imide-containing benzoxazine (PSiBZ) as the matrix and double-decker silsesquioxane (DDSQ) epoxy or polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) epoxy were prepared for improving thermosetting performance. Thermomechanical and dynamic mechanical characterizations indicated that both DDSQ and POSS could effectively lower the coefficient of thermal expansion by up to approximately 34% and considerably increase the storage modulus (up to 183%). Therefore, DDSQ and POSS are promising materials for low-stress encapsulation for electronic packaging applications. Keywords: polysiloxane-imide-containing benzoxazine; polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane epoxy; double-decker silsesquioxane epoxy; polymer nanocomposite 1. Introduction Compared with pristine polymer nanocomposites, hybrid organic–inorganic nanocomposites comprising of functional polymers as the matrix and nanoscale inorganic constituents have attracted greater interest in both academia and industry because of their tunable and generally more favorable thermal, mechanical, electrical, and barrier properties [1–3]. Upgrading current thermosetting polymers has become critical because of their utilization in various applications. -

Contents 1 Properties of Optical Systems

Contents 1 Properties of Optical Systems ............................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Optical Properties of a Single Spherical Surface ........................................................................... 7 1.1.1 Planar Refractive Surfaces .................................................................................................... 7 1.1.2 Spherical Refractive Surfaces ................................................................................................ 7 1.1.3 Reflective Surfaces .............................................................................................................. 10 1.1.4 Gaussian Imaging Equation ................................................................................................. 11 1.1.5 Newtonian Imaging Equation.............................................................................................. 13 1.1.6 The Thin Lens ...................................................................................................................... 13 1.2 Aperture and Field Stops ............................................................................................................ 14 1.2.1 Aperture Stop Definition ..................................................................................................... 14 1.2.2 Marginal and Chief Rays ...................................................................................................... 14 1.2.3 Vignetting ........................................................................................................................... -

Coating System Guide for Chemical & Petrochemical Plants

Coating System Guide for Chemical & Sponsored by Petrochemical Plants Photo: Devoe High Performance Coatings Systems are alphabetized by first coat. Exterior Plant Exposure I Epoxy (1-2 coats)/Urethane I Epoxy/Epoxy 100% Solids Andek Corporation (101-250 g/L) A.W. Chesterton/ARC Composites (<100 g/L) Moderate to Severe Chemical, Coatings For Industry, Inc. (251-340 g/L) Blome International (<100 g/L) Complementary Coatings/DBA Insl-X (251-340 g/L) Corro-Shield International, Inc. Weathering, & UV Corchem Corporation (101-250 g/L) Denso North America Steel Coronado Paint (251-340 g/L) Duromar, Inc. (<100 g/L) Dampney Co., Inc. ENECON Corporation (<100 g/L) Endura Manufacturing Co. Ltd. (101-250 g/L) Gemite Products Inc. (<100 g/L) I Alkyd/Acrylic/Acrylic Devoe Coatings (AkzoNobel) (341-450 g/L) Euronavy Sauereisen, Inc. Diamond Vogel Paint Company (251-340 g/L) Gulf Coast Paint Mfg., Inc. (101-250 g/L) Mascoat Products (<100 g/L) Heresite Protective Coatings, Inc. (341-450 g/L) PolySpec L.P. / THIOKOL (<100 g/L) Highland International, Inc. QUESTMARK FLOORING ITW Futura Coatings (101-250 g/L) Superior Epoxies & Coatings (<100 g/L) KCC Corrosion Control Co., Ltd. Watson Coatings, Inc. Micor Company, Inc. (341-450 g/L) PPG Protective & Marine Coatings (<100 g/L) I Alkyd/Alkyd/Alkyd Richard’s Paint Mfg. Co., Inc. (341-450 g/L) Tnemec Company, Inc. Rust-Oleum Corporation (101-250 g/L) Watson Coatings, Inc. Sherwin-Williams (101-250 g/L) Wolverine Coatings Corporation Specialty Polymer Coatings, Inc. I Calcium Sulphonate I Epoxy/Epoxy Flake Filled/Epoxy Flake Filled Termarust Technologies (101-250 g/L) Tnemec Company, Inc. -

25 Geometric Optics

CHAPTER 25 | GEOMETRIC OPTICS 887 25 GEOMETRIC OPTICS Figure 25.1 Image seen as a result of reflection of light on a plane smooth surface. (credit: NASA Goddard Photo and Video, via Flickr) Learning Objectives 25.1. The Ray Aspect of Light • List the ways by which light travels from a source to another location. 25.2. The Law of Reflection • Explain reflection of light from polished and rough surfaces. 25.3. The Law of Refraction • Determine the index of refraction, given the speed of light in a medium. 25.4. Total Internal Reflection • Explain the phenomenon of total internal reflection. • Describe the workings and uses of fiber optics. • Analyze the reason for the sparkle of diamonds. 25.5. Dispersion: The Rainbow and Prisms • Explain the phenomenon of dispersion and discuss its advantages and disadvantages. 25.6. Image Formation by Lenses • List the rules for ray tracking for thin lenses. • Illustrate the formation of images using the technique of ray tracking. • Determine power of a lens given the focal length. 25.7. Image Formation by Mirrors • Illustrate image formation in a flat mirror. • Explain with ray diagrams the formation of an image using spherical mirrors. • Determine focal length and magnification given radius of curvature, distance of object and image. Introduction to Geometric Optics Geometric Optics Light from this page or screen is formed into an image by the lens of your eye, much as the lens of the camera that made this photograph. Mirrors, like lenses, can also form images that in turn are captured by your eye. 888 CHAPTER 25 | GEOMETRIC OPTICS Our lives are filled with light. -

Predicting Polymers' Glass Transition Temperature by a Chemical

polymers Article Predicting Polymers’ Glass Transition Temperature by a Chemical Language Processing Model Guang Chen 1 , Lei Tao 1 and Ying Li 1,2,* 1 Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, USA; [email protected] (G.C.); [email protected] (L.T.) 2 Polymer Program, Institute of Materials Science, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: We propose a chemical language processing model to predict polymers’ glass transition temperature (Tg) through a polymer language (SMILES, Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) embedding and recurrent neural network. This model only receives the SMILES strings of a polymer’s repeat units as inputs and considers the SMILES strings as sequential data at the character level. Using this method, there is no need to calculate any additional molecular descriptors or fingerprints of polymers, and thereby, being very computationally efficient. More importantly, it avoids the difficulties to generate molecular descriptors for repeat units containing polymerization point ‘*’. Results show that the trained model demonstrates reasonable prediction performance on unseen polymer’s Tg. Besides, this model is further applied for high-throughput screening on an unlabeled polymer database to identify high-temperature polymers that are desired for applications in extreme environments. Our work demonstrates that the SMILES strings of polymer repeat units can be used as an effective feature representation to develop a chemical language processing model for predictions of polymer Tg. The framework of this model is general and can be used to construct structure–property relationships for other polymer properties. Citation: Chen, G.; Tao, L.; Li, Y. -

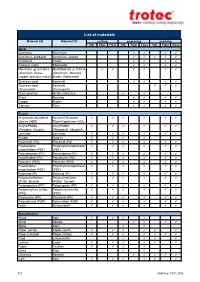

List of Materials

List of materials Material EN Material DE cutting engraving marking CO2 Fiber Flexx CO2 Fiber Flexx CO2 Fiber Flexx Metal Aluminum Aluminium Aluminum, anodized Aluminium, eloxiert Chromium Chrom Precious metal Edelmetall Metal foils up to 0.5mm Metallfolie bis zu 0,5mm (Aluminum, Brass, (Aluminium, Messing, Copper, precious metal) Kupfer, Edelmetall) Stainless steel Edelstahl Stainless steel Edelstahl (Thermark®) (Thermark®) Metal, painted Metall, lackiertes Brass Messing Copper Kupfer Titanium Titan Plastic Acrylonitrile butadiene Acrylnitril-Butadien- styrene (ABS) Styrol-Copolymer (ABS) Acrylic/PMMA Acryl/PMMA (Plexiglas, Altuglas, (Plexiglas®, Altuglas®, LaminatePerspex) LaminatePerspex®) Rubber Gummi Polyamide (PA) Polyamid (PA) Polybutylene Polybutylenterephthalat terephthalate (PBT) (PBT) Polycarbonate (PC) Polycarbonat (PC) Polyethylene (PE) Polyethylen (PE) Polyester (PES) Polyester (PES) Polyethylene Polyethylenterephthalat terephthalate (PET) (PET) Polyimide (PI) Polyimid (PI) Polyoxymethylene Polyoxymethylen (POM) -Delrin® (POM) - Delrin® Polypropylene (PP) Polypropylen (PP) Polyphenylene sulfide Polyphenylensulfid (PPS) (PPS) Polystyrene (PS) Polystyrol (PS) Polyurethane (PUR) Polyurethan (PUR) Foam Schaumstoff Miscellanious Wood Holz Mirror Spiegel Stone Stein Paper (white) Papier (weiß) Paper (colored) Papier (färbig) Food Lebensmittel Leather Leder -

Colorless and Transparent High – Temperature-Resistant Polymer Optical Films – Current Status and Potential Applications in Optoelectronic Fabrications

Chapter 3 Colorless and Transparent high – Temperature-Resistant Polymer Optical Films – Current Status and Potential Applications in Optoelectronic Fabrications Jin-gang Liu, Hong-jiang Ni, Zhen-he Wang, Shi-yong Yang and Wei-feng Zhou Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/60432 Abstract Recent research and development of colorless and transparent high-temperature- resistant polymer optical films (CHTPFs) have been reviewed. CHTPF films possess the merits of both common polymer optical film and aromatic high-temperature- resistant polymer films and thus have been widely investigated as components for microelectronic and optoelectronic fabrications. The current paper reviews the latest research and development for CHTPF films, including their synthesis chemistry, manufacturing process, and engineering applications. Especially, this review focuses on the applications of CHTPF films as flexible substrates for optoelectrical devices, such as flexible active matrix organic light-emitting display devices (AMOLEDs), flexible printing circuit boards (FPCBs), and flexible solar cells. Keywords: colorless polymer films, high temperature, synthesis, flexible substrates 1. Introduction Various polymer optical films have been widely applied in the fabrication of optoelectronic devices [1]. Recently, with the ever-increasing demands of high reliability, high integration, high wiring density, and high signal transmission speed for optoelectronic fabrications, the service temperatures of polymer optical films have dramatically increased [2, 3]. For instance, © 2015 The Author(s). Licensee InTech. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

3 About the Nature of the Structural Glass Transition: an Experimental Approach

3 About the Nature of the Structural Glass Transition: An Experimental Approach J. K. Kr¨uger1,2, P. Alnot1,3, J. Baller1,2, R. Bactavatchalou1,2,3,4, S. Dorosz1,3, M. Henkel1,3, M. Kolle1,4,S.P.Kr¨uger1,3,U.M¨uller1,2,4, M. Philipp1,2,4,W.Possart1,5, R. Sanctuary1,2, Ch. Vergnat1,4 1 Laboratoire Europ´een de Recherche, Universitaire Sarre-Lorraine-(Luxembourg) [email protected] 2 Universit´edu Luxembourg, Laboratoire de Physique des Mat´eriaux,162a, avenue de la Fa¨ıencerie, L-1511 Luxembourg, Luxembourg 3 Universit´eHenriPoincar´e, Nancy 1, Boulevard des Aiguillettes, Nancy, France 4 Universit¨atdes Saarlandes, Experimentalphysik, POB 151150, D-66041 Saarbr¨ucken, Germany 5 Universit¨at des Saarlandes, Werkstoffwissenschaften, POB 151150, D-66041 Saarbr¨ucken, Germany Abstract. The nature of the glassy state and of the glass transition of structural glasses is still a matter of debate. This debate stems predominantly from the kinetic features of the thermal glass transition. However the glass transition has at least two faces: the kinetic one which becomes apparent in the regime of low relaxation frequencies and a static one observed in static or frequency-clamped linear and non-linear susceptibilities. New results concerning the so-called α-relaxation process show that the historical view of an unavoidable cross-over of this relaxation time with the experimental time scale is probably wrong and support instead the existence of an intrinsic glass transition. In order to prove this, three different experimental strategies have been applied: studying the glass transition at extremely long time scales, the investigation of properties which are not sensitive to the kinetics of the glass transition and studying glass transitions which do not depend at all on a forced external time scale. -

Mechanical and Electrical Studies of Silicone Modified Polyurethane

Polymer Journal, Vol. 36, No. 10, pp. 848—855 (2004) Mechanical and Electrical Studies of Silicone Modified Polyurethane–Epoxy Intercrosslinked Networks y Arun ANAND PRABU and Muthukaruppan ALAGAR Department of Chemical Engineering, Anna University, Chennai-600 025, India (Received May 27, 2004; Accepted July 20, 2004; Published October 15, 2004) ABSTRACT: A series of intercrosslinked networks (ICNs) based on silicone modified polyurethane (PU)–epoxy resins were developed. In this study, epoxy resin (diglycidyl ether of bisphenol-A) was modified with PU prepolymer and hydroxyl-terminated polydimethylsiloxane (HTPDMS) using -aminopropyl triethoxysilane ( -APS) as silane cross linker and dibutyltindilaurate (DBTL) as catalyst to form ICNs. Aromatic polyamine adduct (A), diethylenetri- amine (B) and polyamidoamine (C) were used as epoxy curatives. The final products were obtained in the form of tough films. Changes in chemical structure during ICN formation, mechanical and electrical properties were investigated us- ing FT-IR spectra, tensile, impact and dielectric testing. The mechanical properties were enhanced with incorporation of PU (10 wt %) and silicone (10 wt %) due to the toughening of brittle epoxy matrices. Electrical properties showed a marginally decreasing trend with the incorporation of PU (0–20 wt %) influenced by the polar urethane linkages where- as silicone incorporation (10 wt %) showed an enhancement due to the presence of inorganic –Si–O–Si– linkage. Among the systems studied, the silicone (10 wt %) modified PU (10 wt %)–epoxy cured with ‘‘A’’ exhibited excellent mechanical and electrical characteristics and can be used as coatings and composites for industrial, electrical and ma- rine components. [DOI 10.1295/polymj.36.848] KEY WORDS Intercrosslinked Network / Epoxy / Polyurethane / Silicone / Coatings / Composites / Numerous polymeric resins based on epoxy, unsat- used in epoxy and polyurethane synthesis.