Artists Quarantine with Their Art Collections “Looking at the Imagery Is Like Reviewing a Memory Bank.”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magee E-Mail PR

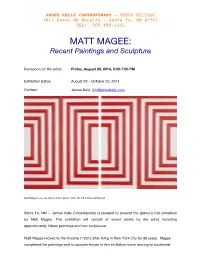

JAMES KELLY CONTEMPORARY - PRESS RELEASE 1611 Paseo de Peralta - Santa Fe, NM 87501 TEL: 505-989-1601 MATT MAGEE: Recent Paintings and Sculpture Reception for the artist: Friday, August 29, 2014, 5:00-7:00 PM Exhibition Dates: August 29 – October 25, 2014 Contact: James Kelly [email protected] Matt Magee, Locus, 2013, Oil on panel, 10 x 16-1/4 inches unframed. Santa Fe, NM -- James Kelly Contemporary is pleased to present the gallery’s first exhibition by Matt Magee. This exhibition will consist of recent works by the artist, including approximately fifteen paintings and four sculptures. Matt Magee moved to the Arizona in 2012 after living in New York City for 30 years. Magee completed the paintings and sculptures shown in this exhibition since moving to southwest two years ago. Magee worked as an archivist for Robert Rauschenberg for 18 years. Before that, as a young adult, he drove a seismic truck in Laredo, Texas, recording vibrations sent into the earth to collect data about underlying geologic formations. His paintings often resemble charts and graphs of collected information, or tablets and iPads with data read-outs. As an archivist, he filled in spreadsheets with inventory numbers and as an artist he fills in these very same grids with paint in works such as Ledger, Xantrion and Stillwater. These paintings also reference how light reflects off the surface of glass skyscrapers and water, and the life implicit behind the glass or under the water. The paint is the information. The pictorial language in Magee's work includes things both observed and imagined. -

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG a W I N G S F R O M T H E 1 9 6 0 S

Transfer Drawings from the 1960s Drawings from Transfer ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG Transfer Drawings from the 1960s ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG Transfer Drawings from the 1960s FEBRUARY 8– MARCH 17, 2007 41 EAST 57TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10022 FOREWORD For me, a roomful of Robert Rauschenberg's “Transfer” drawings from the 1960s evokes a powerful sense of dèjà vu. It's a complicated flash from the past, dense with images and newspaper headlines drawn from the events of the time. Saturn 5 rockets, Apache helicopters, ads for spark plugs, photos of astronauts mix with pictures of motorcycles, flashcubes, wristwatches and razor blades, all taken out of their original contexts and reworked into a web of startling new associations by an artist with a keen sense of popular history heightened by irony and a profound wit. Rauschenberg is like a mollusk in the sea of time, filtering and feeding upon everything that passes through his awareness and transforming it to suit his own ends, like an oyster secreting a pearl. He selects images from popular media as signifiers—telling icons of who we Americans are as a people, a nation and a culture. And the new linkages he creates make us question our assumptions about our identity: where did we come from, what do we really care about, where are we going? Rauschenberg's smart, deliberative art mirrors the American character: self-questioning and proud, defiant and wondering, but always hopeful. It is a great pleasure to re-familiarize the public with these drawings, important both artistically and historically. Many of them are being shown in the United States for the first time since they were originally exhibited in Paris at Galerie Ileana Sonnabend in 1968. -

William Gropper's

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas March – April 2014 Volume 3, Number 6 Artists Against Racism and the War, 1968 • Blacklisted: William Gropper • AIDS Activism and the Geldzahler Portfolio Zarina: Paper and Partition • Social Paper • Hieronymus Cock • Prix de Print • Directory 2014 • ≤100 • News New lithographs by Charles Arnoldi Jesse (2013). Five-color lithograph, 13 ¾ x 12 inches, edition of 20. see more new lithographs by Arnoldi at tamarind.unm.edu March – April 2014 In This Issue Volume 3, Number 6 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Fierce Barbarians Associate Publisher Miguel de Baca 4 Julie Bernatz The Geldzahler Portfoio as AIDS Activism Managing Editor John Murphy 10 Dana Johnson Blacklisted: William Gropper’s Capriccios Makeda Best 15 News Editor Twenty-Five Artists Against Racism Isabella Kendrick and the War, 1968 Manuscript Editor Prudence Crowther Shaurya Kumar 20 Zarina: Paper and Partition Online Columnist Jessica Cochran & Melissa Potter 25 Sarah Kirk Hanley Papermaking and Social Action Design Director Prix de Print, No. 4 26 Skip Langer Richard H. Axsom Annu Vertanen: Breathing Touch Editorial Associate Michael Ferut Treasures from the Vault 28 Rowan Bain Ester Hernandez, Sun Mad Reviews Britany Salsbury 30 Programs for the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre Kate McCrickard 33 Hieronymus Cock Aux Quatre Vents Alexandra Onuf 36 Hieronymus Cock: The Renaissance Reconceived Jill Bugajski 40 The Art of Influence: Asian Propaganda Sarah Andress 42 Nicola López: Big Eye Susan Tallman 43 Jane Hammond: Snapshot Odyssey On the Cover: Annu Vertanen, detail of Breathing Touch (2012–13), woodcut on Maru Rojas 44 multiple sheets of machine-made Kozo papers, Peter Blake: Found Art: Eggs Unique image. -

MATT MAGEE: RANDOM ORDER February 26–May 15, 2021

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MATT MAGEE: RANDOM ORDER February 26–May 15, 2021 VIRTUAL ARTIST TALK Friday, February 26, 2pm (MT) / 4pm (EST) With Print Curator Kylee Aragon Wallis SATELLITE SHOW AT RADIUS BOOKS February 26–May 15, 2021 Matt Magee, Burst, 2020, Gold Foil on Arches MATT MAGEE: LOOKING BACK (AND UP, DOWN AND SIDE TO SIDE) (February 2021) Zane Bennett Contemporary Art is delighted to announce Random Order by American conceptual and experimental artist Matt Magee. Random Order marks the first solo exhibition of Magee’s work at the gallery. A virtual artist talk between Magee and Print Curator Kylee Aragon Wallis will be held over Instagram Live on Opening Day, Friday, February 26 at 2pm (MT). An accompanying Satellite Show of works completed during the artist’s 2019 residency with Michael Woolworth in Paris will also be on view at the offices of Radius Books throughout the duration of Random Order. Magee’s monograph with Radius Books will also be available for purchase through the gallery. A book signing event in collaboration with Radius will be announced soon, to be held in early May. Random Order is currently open by appointment: email [email protected] or call (505) 982-8111 to schedule a masked visit. A selection of predominantly never-before-seen pieces that focus on the artist’s ongoing interest in playful permutations of bold forms and repurposed unconventional materials will be featured. Magee’s prolific and thoughtful output positively buzzes—like the grids and information systems he often visualizes—with forward-thinking ideas and art historical riffs. -

Media Contacts: for Immediate Release: August 23, 2016 EXPO

Media Contacts: EXPO CHICAGO Press Agency: Carly Leviton/Arielle Ismail, Carol Fox and Associates 773.969.5034/[email protected] 773.969.5043/[email protected] Taylor Maatman, FITZ & CO 646.589.0926/[email protected] David Ulrichs, David Ulrichs PR +4917650330135/[email protected] For Immediate Release: August 23, 2016 EXPO CHICAGO ANNOUNCES SELECTED ARTISTS FOR IN/SITU, IN/SITU OUTSIDE AND EXPO PROJECTS A Break in the Code, The 2016 IN/SITU Program Curated by Diana Nawi, and EXPO Projects To Be on Display at Fifth Edition Sept. 22 – 25, 2016 IN/SITU Outside, Presented in Collaboration with The Chicago Park District and The City of Chicago’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events, and OVERRIDE | A Billboard Project, to be Sited in Public Locations Throughout Chicago CHICAGO — EXPO CHICAGO, The International Exposition of Modern & Contemporary Art, announces the full program of artists selected for IN/SITU, EXPO Projects, IN/SITU Outside and OVERRIDE | A Billboard Project. IN/SITU, curated by Pérez Art Museum Miami Associate Curator Diana Nawi, features large-scale installations and site-specific work situated throughout Navy Pier’s Festival Hall, alongside EXPO Projects, featuring a curated selection of works organized by EXPO CHICAGO (Sept. 22 – 25, 2016). Selected from the 145 exhibiting galleries at EXPO CHICAGO, this year’s IN/SITU program, A Break in the Code, is anchored by the first piece specifically designed for EXPO CHICAGO, Bettina Pousttchi’s Rotunda (2016). Located above the center plaza of the show floor as a main focal point of the exposition, the plaza piece will be joined by highlights including Spencer Finch, Victoria Fu, Rodney McMillian, Julio César Morales and For Freedoms, among others. -

Magee PR.Pages

January 12, 2016 Contact: Viviette Hunt, Director, or Chelsea Wrightson, Gallery Assistant [email protected] 505.766.9888 Seven: A Survey of Paintings by Matt Magee FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 11–April 15 First Friday Gallery Reception: April 1, 6:00–8:00 pm Richard Levy Gallery is pleased to present Seven, a survey of paintings from the last seven years by Matt Magee. Counting the days in a week, seas, continents, and colors in a rainbow, Magee meditates on the number 7 both visually and sequentially in his work. Magee’s compositions are organizations of shapes that have been informed by personal history, numerology, and language. In his early years Magee found a sense of order from his father, a geologist and archaeologist, who took him on trips through the Southwest where he collected small objects along the way. As a young adult he worked on a seismic truck in Laredo, TX and recorded vibrations sent into the earth to determine underlying geologic formations. Later, Magee was the chief photo archivist for the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Throughout his life, he has established ways of collecting that now inform his painting practice. Magee’s painting style is minimal in concept, but his brushstrokes are expressive. Within these conceptual spreadsheets, abacuses, and hieroglyphics are reminders of the artist’s hand. His visual language relates to early hard-edge abstraction and finds inspiration in contemporary scientific, ecological, and technological ideas. Over a career spanning more than four decades, Magee has been a Josef and Anni Albers Foundation resident fellow, a New York Foundation for the Arts Painting Grant recipient, and a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant recipient. -

PAINTINGS and TEXTCAVATIONS New Work by MATT MAGEE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PAINTINGS AND TEXTCAVATIONS New work by MATT MAGEE November 5 – December 5, 2015 Opening Reception: Thursday, November 5, 6-8pm John Molloy Gallery is pleased to announce PAINTINGS & TEXTCAVATIONS: new work by Matt Magee, opening on November 5, 2015 with a reception for the artist from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. The show runs until December 5. Fresh from his second residency at the Anni & Josef Albers Foundation, Magee adds new materials and insights to his already impressive body of work. Drawing on the signposts of our age, from the literal signs we see on interstate highways to the texts we view on our phones, to the clusters of lights that crowd urban landscapes at night, Magee has synthesized these forms into his own vision of painting and assemblage. Whether in the age-old process of paint or ink on a blank surface or in a new process of cut-up aluminum cans arranged on a board or an orderly attachment of pebbles on boards, Magee's work makes us look at our world Matt Magee, Aluminum Circuit 3, 2015, aluminum on anew. Grounded in ancient traditions of map-making in aluminum sheet,, 15 ½ X 15 ½ inches framed Polynesia and Australia, Magee utilizes the common threads that cross cultural traditions to create a new way of seeing. Symbols permeate the exhibition. They are taken from daily life and gain new meaning through an exploration of their formal qualities. The format for INGOT is borrowed from the shape of Koranic verse at the Topkapi. STUDY FOR NARITA and STUDY FOR FRANKFORT are based on airport floorplans and WINDOW is informed by a window at the Hagia Sofia. -

Art on Paper Returns for Third Edition***

For Immediate Release Media Contact: Kelly Freeman, Director 212.518.6912 / [email protected] ***Art on Paper Returns for Third Edition*** The Celebrated Paper Fair Returns to Pier 36 in March 2017 featuring notable new and returning exhibitors New York, New York - January 16, 2017 - Art on Paper announces its return to Lower Manhattan’s Pier 36 for the fair’s anticipated third edition, taking place March 2 - 5, 2017. Over seventy-five top galleries from around the world will present paper-based art that explores, expands, and re-imagines the boundaries of what a work on paper can be alongside an innovative program of installations and special projects that will activate the fair’s public spaces. Joining fellow first time exhibitors including Pentimenti Gallery, JONATHAN FERRARA GALLERY, PDX Contemporary Art, Gallery Poulsen, Littlejohn Contemporary, Kraushaar Galleries, and Stoney Road Press, Tamarind Institute will exhibit lithographs by Tara Donovan, Nicola López, and Robert Pruitt. Art on Paper welcomes back notable returning exhibitors to the fair's third edition including Sasha Wolf Projects, Center Street Studio, Dolan/Maxwell, Margaret Thatcher Projects, Traywick Contemporary, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Other Criteria, all presenting significant projects exploring the boundaries of what a work on paper can be. Walter Maciel Gallery will return to present a large-scale, mixed media installation by Timothy Paul Myers, joining Nancy Hoffman Gallery exhibiting never before seen 1970's black and white photographs by Don Eddy, Forum Gallery exhibiting paper constructions by Cybèle Young and 1950's watercolor by Andrew Wyeth, Richard Levy Gallery showing work by Alex Katz, Hayley Rheagan, Polly Apfelbaum, and Matt Magee, and The Proposition exhibiting a solo presentation of watercolor on paper by Balint Zsako. -

Color Rhythms, a Group Exhibition of Artists Working in the Abstract

! ! FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE !April 25-May 30, 2014 Richard Levy Gallery is pleased to present Color Rhythms, a group exhibition of artists working in the abstract. This exhibition includes work by Anna Bogatin, Suzanne Caporael, Jeff Kellar, !and Matt Magee. Philadelphia-based artist Anna Bogatin finds inspiration for her meditative and meticulous drawings and paintings in the sky and the surface of the ocean. Her work achieves balance between elements of color and shape and largely refers to the patterning of nature. Born in the Ukraine, Bogatin has lived and worked as an artist in the United States since 1992 and has exhibited at the Philadelphia Museum of Arts and the Orange County Center for !Contemporary Art, among others. Inspired by thousands of miles of back roads traveled in the U.S. over a period of four years, Suzanne Caporael’s collages are constructed from cut-up New York Times articles collected along the way. Through explorations of color and form, these newspaper collages provide a glimpse into her creative process. For Caporael, these arrangements function as sketches and source material for future paintings, though most are never glued down. Her work is in the collections of the Carnegie Institute, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the High Museum !of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Whitney Museum of Art. Formal, cool, and reserved, Jeff Kellar’s paintings are bold, geometric compositions. His minimal abstractions comprise many layers of burnished clay pigment and resin on aluminum panels. Although rendered with precision, slight irregularities and textures in the work reveal the presence of the artist’s hand. -

If You Stay Busy You Have No Time to Be Unhappy

GREAT HALL If You Stay Busy You Have No Time To Be Unhappy 60. 61. 58. 59. 14. 13. 62. 57. 10. 11. 64. 9. 12. 65. 63. 67. 66. 68. 55. 69. 54. 52. 44. 41. 40. 56. 53. 51. 50. 49. 48. 47. 46. 45. 43. 42. 39. 38. 37. 36. 35. 16. 15. 8. 71. 70. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 24. 26. 27. 29. 32. 33. 73. 72. 17. 23. 25. 28. 30. 31. 34. 75. 74. 76. 77. 78. 4. 81. 80. 7. 79. 82. 5. 6. 3. 84. 83. 85. 2. 1. 1. Alex Von Bergen CBRE #2, 2017, Inkjet print on 4. Alois Kronschlaeger Basin and Range Model, 2013 vinyl, sign substrate, wood posts. 84 x 60 x 4” Wood, wire, latex. 3 x 4 x 2’ 2. Jessica James Lansdon Heraldry, 2017 Vinyl, 5. Wylwyn Dominic Reyes By the Roadside, 2017 nylon rope, acrylic. 10 x 60’ Steel, cable, found objects. 18 x 4 x 4’ 3. Andrew Shuta We are living in a recurring 6. Eli Burke Summerland, 2017 Mixed media. nightmare, 2017 MDF, plaster, plastic, paint, black 4 x 4 x 8’ light, extension cords, hoodie. 7. Danie Enriquez Spare Parts For Sale, 2017 26. Jim Damron Castle Eileen Donan from the Homemade Cold Porcelain, Sculpey, Plaster of Paris, South, 2015 Oil on MDF. 3 x 3” Acrylic paints, nail polish, ribbon, jewelry parts, wire. 27. Butt Johnson MOCA Street View, 2017 Marker on 18 x 10” paper. 6 x 7 ½” Will Peterson Lithocubus Prototype, 2013-2017 8. 28. Al Perry The Desert Scene, 2016 Watercolor on Aluminum frame, steel hardware, polypropylene paper. -

78 Psu FOOTBALL Key Moments

TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: THE COACHES SECTION 6: 2016 REVIEW SECTION 9: OPPONENTS Head Coach Tim Beck............................................... 2-4 2017 Results............................................................. 70 The MIAA ................................................................144 Assistant Head Coach David Weimers ...........................5 2017 Stats ............................................................70-75 The MIAA in the Playoffs ..........................................145 Defensive Coordinator Nate Dreiling .............................6 2017 MIAA Review ...................................................146 Matt Karleskint ...........................................................7 SECTION 7: HISTORY Yearly MIAA Standings .............................................147 Josh Lattimer .............................................................7 MIAA Records ...................................................148-152 John Pierce ................................................................8 Football History ....................................................76-77 Carl Roth ....................................................................8 Playoff History .......................................................... 77 Keeston Terry .............................................................9 Key Moments ........................................................78-79 SECTION 11: PITTSBURG State UNIVERSITY Steve Wells .................................................................9 Conference -

Fall 2020.Indd

The Print Club of New York Inc Fall 2020 fairs virtually again soon. President’s Greeting I’d also like to recognize the Club’s most recent and Kimberly Henrikson very first virtual event, our Annual Artist Talk with Victoria Burge, who produced this year’s Presentation Greetings PCNY Members, Print for our members. In addition, we were joined by t is Fall 2020, and our new membership year is under- Luther Davis from Powerhouse Arts, who was the Master way, albeit a bit differently than in past years. This Printer for Victoria’s print. My thanks to Allison Tolman year with the ongoing restrictions for gatherings due for making that happen and for insuring that it went as I smoothly as it did. I was pleased to see that for our first to concerns about COVID-19, as many other organizations have done, we also have made changes to much of our webinar and remote presentation, we had a strong show- outreach and programming to allow for remote participa- ing of attendees. The video has been shared out via email tion, relying more on web-based activities and communi- for those who could not attend or who wish to view it cations. I have been so impressed with the scope of ideas again. We’ll also be posting that to our website for refer- and willingness to try new things while taking on new ence. The prints will be distributed to members in the responsibilities from the board members of this Club. coming weeks, and as Luther pointed out, the inks used Their thoughtfulness and enthusiasm insure that we are produce a raised surface on the prints, giving them a sort doing all we can to provide our members with opportuni- of unique textural element.