Gifford Pinchot's Arkansas Adventure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George M. Leader, 1918-2013 Michael J

Gettysburg College Faculty Books 2014 George M. Leader, 1918-2013 Michael J. Birkner Gettysburg College Charles H. Glatfelter Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/books Part of the Cultural History Commons, Oral History Commons, Public History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Birkner, Michael J. and Charles H. Glatfelter. George M. Leader, 1918-2013. Musselman Library, 2014. Second Edition. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/books/78 This open access book is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. George M. Leader, 1918-2013 Description George M. Leader (1918-2013), a native of York, Pennsylvania, rose from the anonymous status of chicken farmer's son and Gettysburg College undergraduate to become, first a State Senator, and then the 36th governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. A steadfast liberal in a traditionally conservative state, Leader spent his brief time in the governor's office (1955-1959) fighting uphill battles and blazing courageous trails. He overhauled the state's corrupt patronage system; streamlined and humanized its mental health apparatus; and, when a black family moved into the white enclave of Levittown, took a brave stand in favor of integration. -

The Teacher and the Forest: the Pennsylvania Forestry Association, George Perkins Marsh, and the Origins of Conservation Education

The Teacher and The ForesT: The Pennsylvania ForesTry associaTion, GeorGe Perkins Marsh, and The oriGins oF conservaTion educaTion Peter Linehan ennsylvania was named for its vast forests, which included well-stocked hardwood and softwood stands. This abundant Presource supported a large sawmill industry, provided hemlock bark for the tanning industry, and produced many rotations of small timber for charcoal for an extensive iron-smelting industry. By the 1880s, the condition of Pennsylvania’s forests was indeed grim. In the 1895 report of the legislatively cre- ated Forestry Commission, Dr. Joseph T. Rothrock described a multicounty area in northeast Pennsylvania where 970 square miles had become “waste areas” or “stripped lands.” Rothrock reported furthermore that similar conditions prevailed further west in north-central Pennsylvania.1 In a subsequent report for the newly created Division of Forestry, Rothrock reported that by 1896 nearly 180,000 acres of forest had been destroyed by fire for an estimated loss of $557,000, an immense sum in those days.2 Deforestation was also blamed for contributing to the pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 79, no. 4, 2012. Copyright © 2012 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Wed, 14 Mar 2018 16:19:01 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms PAH 79.4_16_Linehan.indd 520 26/09/12 12:51 PM the teacher and the forest number and severity of damaging floods. Rothrock reported that eight hard-hit counties paid more than $665,000 to repair bridges damaged from flooding in the preceding four years.3 At that time, Pennsylvania had few effective methods to encourage forest conservation. -

Forestry Education at the University of California: the First Fifty Years

fORESTRY EDUCRTIOfl T THE UflIVERSITY Of CALIFORflffl The first fifty Years PAUL CASAMAJOR, Editor Published by the California Alumni Foresters Berkeley, California 1965 fOEUJOD T1HEhistory of an educational institution is peculiarly that of the men who made it and of the men it has helped tomake. This books tells the story of the School of Forestry at the University of California in such terms. The end of the first 50 years oi forestry education at Berkeley pro ides a unique moment to look back at what has beenachieved. A remarkable number of those who occupied key roles in establishing the forestry cur- riculum are with us today to throw the light of personal recollection and insight on these five decades. In addition, time has already given perspective to the accomplishments of many graduates. The School owes much to the California Alumni Foresters Association for their interest in seizing this opportunity. Without the initiative and sustained effort that the alunmi gave to the task, the opportunity would have been lost and the School would have been denied a valuable recapitulation of its past. Although this book is called a history, this name may be both unfair and misleading. If it were about an individual instead of an institution it might better be called a personal memoir. Those who have been most con- cerned with the task of writing it have perhaps been too close to the School to provide objective history. But if anything is lost on this score, it is more than regained by the personalized nature of the account. -

Native Plants and Genetics Program

United States Department of Agriculture Native Forest Service Pacific Northwest Plants & Region Genetics Program Accomplishments Volunteers plant at Maple Loop on the Methow, RD. Native seed processed at R6 Iris tenax from Willamette NF Fiscal Year 2015 Bend Seed Extractory ready for in production at NRCS sowing Corvallis Plant Material Center U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

The Shelterbelt “Scheme”: Radical Ecological Forestry and the Production Of

The Shelterbelt “Scheme”: Radical Ecological Forestry and the Production of Climate in the Fight for the Prairie States Forestry Project A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY MEAGAN ANNE SNOW IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Roderick Squires January 2019 © Meagan A. Snow 2019 Acknowledgements From start to finish, my graduate career is more than a decade in the making and getting from one end to the other has been not merely an academic exercise, but also one of finding my footing in the world. I am thankful for the challenge of an ever-evolving committee membership at the University of Minnesota’s Geography Department that has afforded me the privilege of working with a diverse set of minds and personalities: thank you Karen Till, Eric Sheppard, Richa Nagar, Francis Harvey, and Valentine Cadieux for your mentorship along the way, and to Kate Derickson, Steve Manson, and Peter Calow for stepping in and graciously helping me finish this journey. Thanks also belong to Kathy Klink for always listening, and to John Fraser Hart, an unexpected ally when I needed one the most. Matthew Sparke and the University of Washington Geography Department inspired in me a love of geography as an undergraduate student and I thank them for making this path possible. Thank you is also owed to the Minnesota Population Center and the American University Library for employing me in such good cheer. Most of all, thank you to Rod Squires - for trusting me, for appreciating my spirit and matching it with your own, and for believing I am capable. -

Pinchot Preserve Branford

MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE PINCHOT PRESERVE Plan developed by Caitlin Cusack for the Branford Land Trust and the Guilford Land Conservation Trust April,2008 Page I I. INTRODUCTION B. Statement of purpose The purpose of this plan is to guide the Branford Land Trust (BLT) and Guildford Land Conservation Trust (GLCT) in making future management decisions concerning the Pinchot Preserve that balances public use and enjoyment with the protection of the preserve's ecological and cultural integrity. The management plan describes the natural and cultural resources and management goals for the Pinchot property. Recommendations for management and restoration actions needed to preserve, protect, and restore the Preserve's natural habitats, significant species populations, and cultural resources are also included. C. General property description 1. Physical characteristics The 47-acre Pinchot Preserve is situated in a key location between the 300 acre preserved Quarry Property, Westwood Trails system, Towner Swamp and the salt marshes of Long Island Sound. As shown in Figure 1, the Pinchot Preserve is located off of Route 146 (Leetes Island Road) in the towns of Branford and Guilford, Connecticut. The Pinchot Preserve can be directly accessed off of Route 146. The parking lot is located east of the salt marsh right before Leetes Island Road crosses under the railroad tracks. The Pinchot Preserve is part of a larger Ill-acre Hoadley Creek Preserve system, which can be accessed at the north end by Quarry Road off of Route 146. The Pinchot Preserve's rolling terrain has a diversity of estuarine and upland habitats and natural features including mixed hardwood forest, a salt marsh, salt water panne, freshwater pond, and vernal pool. -

Bernhard Fernow Was Particularly Interested in the Development and Dissemination of Scientific Data on Forestry’S Environmental Impact and Economic Import

As the third chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry (1886–98), Bernhard Fernow was particularly interested in the development and dissemination of scientific data on forestry’s environmental impact and economic import. A prolific writer and energetic organizer, Fernow had a hand in the creation of local and state forestry associations as well as of forestry colleges in the U.S. and Canada, giving the profession a powerful boost in its formative years. Bernhard Fernow ON FOREST INFLUENCES AND OTHER OBSERVATIONS n 1898, Bernhard E. Fernow, third chief of the Division of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture, responded in 401 pages of detail to Secretary of IAgriculture James Wilson’s request for a statement of accomplishments during Fernow’s twelve-year tenure as agency head. His report—Forestry Investigations and Work of the Department of Agriculture—provides Service. The record reflects his substantial technical a rich reference to American forestry during the skills, including authoring three books, many arti- last two decades of the nineteenth century. cles, and translating German forestry reports into Fernow was born in 1851 in Germany English. The record also shows that he was ill- and was college educated in forestry. He suited by temperament to work in the polit- abandoned a promising forestry career ical arena of Washington, D.C., where real and immigrated to the United States in and imagined slights by superiors occurred 1876 to marry his American sweet- all too frequently. Being treated as an heart, becoming a U.S. citizen in 1882. “underling,” to use his term, was Fernow’s By that time, he was much involved in worst nightmare. -

The Twenty-Ninth Convention of the Pennsylvania Historical Association

THE TWENTY-NINTH CONVENTION OF THE PENNSYLVANIA HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION vYA\RI HooGFNB00M, Secretary R OL- GltiLY one hundred and twenty-five members and guests of the Pennsylvania Historical Association attended its Twenty-ninth Annual TMeeting at Bucknell University on Friday and Saturday, October 14 and 15, 1960. For most of those at- tending the convention, Friday began with a beautiful drive through some portion of Penn's woods. During and after registra- tion in the lobby of Roberts Hall old friends were greeted and new acquaintances were made. The opening luncheon session was held in the John Houghton liarri D1ining Room in Swartz Hall. J. Orin Oliphant, Professor of 11 istorv at Bucknell, presided, Douglas E. Sturm, Assistant I 'rofessor of Religion at Bucknell, delivered the invocation, and xRalph A. Cordier, President of the Pennsylvania Historical As- sociation. responded to the greetings of Bucknell's President, -Merle M. Odgers. The main address of this luncheon, given by Larry Gara. Professor of History at Grove City College, was entitled "William Still and the Underground Railroad." Gara pioiiited out that most accounts of the underground railroad accent the achievements of white abolitionists rather than those of Negro meumhei-s of V/ioilance Committees or of the fugitives themselves. l he neglected role of the Negro in the underground railway is graphically portrayed by the career of William Still. For fourteen years Still served the Pennsylvania Abolitionist Society and as a key member of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee spirited many slaves through Philadelphia. To emphasize the Negro's con- tribution, Still published the Unidergroitnd Rail Road in 1872. -

HISTORY of PENNSYLVANIA's STATE PARKS 1984 to 2015

i HISTORY OF PENNSYLVANIA'S STATE PARKS 1984 to 2015 By William C. Forrey Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Office of Parks and Forestry Bureau of State Parks Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Copyright © 2017 – 1st edition ii iii Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. vii CHAPTER I: The History of Pennsylvania Bureau of State Parks… 1980s ............................................................ 1 CHAPTER II: 1990s - State Parks 2000, 100th Anniversary, and Key 93 ............................................................. 13 CHAPTER III: 21st CENTURY - Growing Greener and State Park Improvements ............................................... 27 About the Author .............................................................................................................................................. 58 APPENDIX .......................................................................................................................................................... 60 TABLE 1: Pennsylvania State Parks Directors ................................................................................................ 61 TABLE 2: Department Leadership ................................................................................................................. -

All in the Family: the Pinchots of Milford Char Miller Trinity University

All in the Family: The Pinchots of Milford Char Miller Trinity University "Little that happened in [Gifford] Pinchot's childhood gave a hint of the calling he would follow," M. Nelson McGeary asserted in the prologue to his biography of the dynamic Progressive reformer. "Certainly the climate of his early upbringing encouraged acceptance of things as they were."' Strictly speaking, McGeary's assertion is true enough. Nowhere in James and Mary Eno Pinchot's voluminous correspondence is there even a hint that they expected their first born to make the mark he did on the United States in the early 20th-century: to become one of the central architects of the conser- vation movement while serving as first chief of the Forest Service; to help manage Theodore Roosevelt's Bull Moose campaign; or serve so successfully as a two-time governor of Pennsylvania. For a biographer to have evidence of such aspirations would have been astonishing-even in parents as ambitious for their children as were the Pinchots. Such a lack of documentary evidence thus turns McGeary's claim into one of those tropes that biographers occa- sionally employ to gloss over what seems unexplainable. Nonetheless, if it appears odd that Pinchot, who was raised in lavish sur- roundings should have matured into someone who apparently was delighted to enter the political arena and there to challenge "things as they were," per- haps the problem lies in the biographer's perspective. For the Pinchots were not at all surprised at the thrust and trajectory of their son's career in politics. -

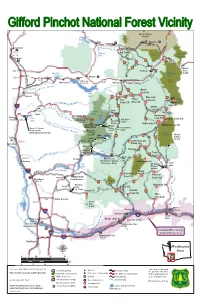

Gifford Pinchot National Forest Overview

Gifford Pinchot National Forest Vicinity ST507 Mount Rainier 14,410' Alder 7 Lake ST Glacier Elbe View Paradise !] ST123 Ashford !] ST706 ST5 Centralia !] !9 Exit 81 Mineral Big Creek William O. Exit 79 Lake CG Tatoosh Douglas Chehalis La Wis 52 !9 !] 9 Wis CG 985 984 47 9 ¤£12 White Exit 71 Packwood!] Pass 508 ST Mayfield Packwood 4,500' Lake Lake Exit 68 Salkum Morton !] ¤£12 !\ Cowlitz Valley Goat Riffe Lake £12 !@ Rocks Mossyrock Overlook ¤ Randle Ranger Station Exit 63 923 North Riffe 25 Fork CG 505 9 !9 Toledo ST Lake 76 !9 926 !9 9 Blue Lake 21 Tower 9 Iron Creek CG !9Walupt Creek CG Rock CG !9 Walupt Lake Lake CG ¨¦§5 925 Adams ST504 956 Bear Fork CG ST504 Coldwater Lake Meadow !9 Toutle Spirit 999 Horseshoe !] !\ Castle Silver !\ Lake Lake CG !9 Elk Pass 923 Killen Creek CG Rock Exit 49 Lake Elk Rock !9 Cascade 4,075' !9 3,760' !@ Peaks Olallie Lake CG !9 Johnston Ridge Windy Takhlakh Lake CG Observatory Mount St. Helens Ridge !\ Clearwater Visitor Center Mount St. 4,170' 3,200' Helens Mount (Washington State Parks) Lava 8,328' Mount Ape Canyon 925 9908 Adams Kelso Canyon 923 Adams Climber's 12,276' Exit 39 Bivouac !9 Lower Falls CG Longview & Day Use Ape Cave !9 924 Tillicum CG Trail of Swift Two Forests Reservoir Trout 988 !] 30 Creek CG McClellan 9 Exit 32 !9 Cougar Pine Creek !\ !9 Kalama Information Station Cultus Creek CG (Summers Only) Trout 503 Yale Mt.Adams ST Indian Lake Lake Ranger !@ Heaven Station 5 Lake Merwin Goose ¨¦§ Paradise !9 !9 Lake CG Peterson !@ Creek CG !9 !] Amboy MSHNVM Prairie CG ST141 Woodland Headquarters Trapper Exit 21 54 60 9 Creek 9 Moulton Oklahoma CG Yacolt Falls Beaver CG !9 Co. -

The Pinchots and the Greatest Good: How One Family Improved Social Justice and Civil Rights in America

The Pinchots and The Greatest Good: How One Family Improved Social Justice and Civil Rights in America The Pinchot family women; supported the arts; founded Liberties Bureau, a group of lawyers who has a long- and supported civil rights organizations; offered pro bono defense of cases that standing goal of campaigned tirelessly for the rights of protected basic civil liberties such as free conservation, workers, women, and children; and speech, free press, peaceful assembly, civil rights, much more. Few wealthy families of the liberty of conscience, and freedom from and social nineteenth century can point with pride search and seizure. The Little Civil justice. to such dedicated efforts on behalf of the Liberties Bureau eventually became the Gifford less fortunate. American Civil Liberties Union. Amos Pinchot was The U.S. Forest Service and its partners served on its Board until his death. not just a continue to explore this family’s efforts conservationist to improve the basic human rights that Cornelia Pinchot: and a forester— we enjoy today. Grey Towers National Cornelia, Gifford he was a trust Historic Site, Pinchot’s ancestral home Pinchot’s wife, buster, fearless Gifford Pinchot in Milford, PA, continues to deliver was a suffragette explorer, and a public programs and interpretive tours who helped get proponent of public electric power. He to thousands of visitors annually. women the fought the corruption in which the rich right to vote. and powerful dominated the agenda of These Pinchot family members continue She worked government. to inspire us and our visitors: tirelessly for Pinchot is known for reforming how Amos Pinchot: public good, forests in the United States were At the risk of helping to put managed and developed and for alienating himself an end to child advocating the conservation of the from his family labor, taking a stand Nation’s forest reserves through planned and his niche in against low pay Cornelia Pinchot use and renewal.