Evaluating the Effects of Varying Levels and Patterns of Green-Tree Retention: Experimental Design of the DEMO Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George M. Leader, 1918-2013 Michael J

Gettysburg College Faculty Books 2014 George M. Leader, 1918-2013 Michael J. Birkner Gettysburg College Charles H. Glatfelter Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/books Part of the Cultural History Commons, Oral History Commons, Public History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Birkner, Michael J. and Charles H. Glatfelter. George M. Leader, 1918-2013. Musselman Library, 2014. Second Edition. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/books/78 This open access book is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. George M. Leader, 1918-2013 Description George M. Leader (1918-2013), a native of York, Pennsylvania, rose from the anonymous status of chicken farmer's son and Gettysburg College undergraduate to become, first a State Senator, and then the 36th governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. A steadfast liberal in a traditionally conservative state, Leader spent his brief time in the governor's office (1955-1959) fighting uphill battles and blazing courageous trails. He overhauled the state's corrupt patronage system; streamlined and humanized its mental health apparatus; and, when a black family moved into the white enclave of Levittown, took a brave stand in favor of integration. -

Native Plants and Genetics Program

United States Department of Agriculture Native Forest Service Pacific Northwest Plants & Region Genetics Program Accomplishments Volunteers plant at Maple Loop on the Methow, RD. Native seed processed at R6 Iris tenax from Willamette NF Fiscal Year 2015 Bend Seed Extractory ready for in production at NRCS sowing Corvallis Plant Material Center U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

Pinchot Preserve Branford

MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE PINCHOT PRESERVE Plan developed by Caitlin Cusack for the Branford Land Trust and the Guilford Land Conservation Trust April,2008 Page I I. INTRODUCTION B. Statement of purpose The purpose of this plan is to guide the Branford Land Trust (BLT) and Guildford Land Conservation Trust (GLCT) in making future management decisions concerning the Pinchot Preserve that balances public use and enjoyment with the protection of the preserve's ecological and cultural integrity. The management plan describes the natural and cultural resources and management goals for the Pinchot property. Recommendations for management and restoration actions needed to preserve, protect, and restore the Preserve's natural habitats, significant species populations, and cultural resources are also included. C. General property description 1. Physical characteristics The 47-acre Pinchot Preserve is situated in a key location between the 300 acre preserved Quarry Property, Westwood Trails system, Towner Swamp and the salt marshes of Long Island Sound. As shown in Figure 1, the Pinchot Preserve is located off of Route 146 (Leetes Island Road) in the towns of Branford and Guilford, Connecticut. The Pinchot Preserve can be directly accessed off of Route 146. The parking lot is located east of the salt marsh right before Leetes Island Road crosses under the railroad tracks. The Pinchot Preserve is part of a larger Ill-acre Hoadley Creek Preserve system, which can be accessed at the north end by Quarry Road off of Route 146. The Pinchot Preserve's rolling terrain has a diversity of estuarine and upland habitats and natural features including mixed hardwood forest, a salt marsh, salt water panne, freshwater pond, and vernal pool. -

The Twenty-Ninth Convention of the Pennsylvania Historical Association

THE TWENTY-NINTH CONVENTION OF THE PENNSYLVANIA HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION vYA\RI HooGFNB00M, Secretary R OL- GltiLY one hundred and twenty-five members and guests of the Pennsylvania Historical Association attended its Twenty-ninth Annual TMeeting at Bucknell University on Friday and Saturday, October 14 and 15, 1960. For most of those at- tending the convention, Friday began with a beautiful drive through some portion of Penn's woods. During and after registra- tion in the lobby of Roberts Hall old friends were greeted and new acquaintances were made. The opening luncheon session was held in the John Houghton liarri D1ining Room in Swartz Hall. J. Orin Oliphant, Professor of 11 istorv at Bucknell, presided, Douglas E. Sturm, Assistant I 'rofessor of Religion at Bucknell, delivered the invocation, and xRalph A. Cordier, President of the Pennsylvania Historical As- sociation. responded to the greetings of Bucknell's President, -Merle M. Odgers. The main address of this luncheon, given by Larry Gara. Professor of History at Grove City College, was entitled "William Still and the Underground Railroad." Gara pioiiited out that most accounts of the underground railroad accent the achievements of white abolitionists rather than those of Negro meumhei-s of V/ioilance Committees or of the fugitives themselves. l he neglected role of the Negro in the underground railway is graphically portrayed by the career of William Still. For fourteen years Still served the Pennsylvania Abolitionist Society and as a key member of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee spirited many slaves through Philadelphia. To emphasize the Negro's con- tribution, Still published the Unidergroitnd Rail Road in 1872. -

HISTORY of PENNSYLVANIA's STATE PARKS 1984 to 2015

i HISTORY OF PENNSYLVANIA'S STATE PARKS 1984 to 2015 By William C. Forrey Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Office of Parks and Forestry Bureau of State Parks Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Copyright © 2017 – 1st edition ii iii Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. vii CHAPTER I: The History of Pennsylvania Bureau of State Parks… 1980s ............................................................ 1 CHAPTER II: 1990s - State Parks 2000, 100th Anniversary, and Key 93 ............................................................. 13 CHAPTER III: 21st CENTURY - Growing Greener and State Park Improvements ............................................... 27 About the Author .............................................................................................................................................. 58 APPENDIX .......................................................................................................................................................... 60 TABLE 1: Pennsylvania State Parks Directors ................................................................................................ 61 TABLE 2: Department Leadership ................................................................................................................. -

All in the Family: the Pinchots of Milford Char Miller Trinity University

All in the Family: The Pinchots of Milford Char Miller Trinity University "Little that happened in [Gifford] Pinchot's childhood gave a hint of the calling he would follow," M. Nelson McGeary asserted in the prologue to his biography of the dynamic Progressive reformer. "Certainly the climate of his early upbringing encouraged acceptance of things as they were."' Strictly speaking, McGeary's assertion is true enough. Nowhere in James and Mary Eno Pinchot's voluminous correspondence is there even a hint that they expected their first born to make the mark he did on the United States in the early 20th-century: to become one of the central architects of the conser- vation movement while serving as first chief of the Forest Service; to help manage Theodore Roosevelt's Bull Moose campaign; or serve so successfully as a two-time governor of Pennsylvania. For a biographer to have evidence of such aspirations would have been astonishing-even in parents as ambitious for their children as were the Pinchots. Such a lack of documentary evidence thus turns McGeary's claim into one of those tropes that biographers occa- sionally employ to gloss over what seems unexplainable. Nonetheless, if it appears odd that Pinchot, who was raised in lavish sur- roundings should have matured into someone who apparently was delighted to enter the political arena and there to challenge "things as they were," per- haps the problem lies in the biographer's perspective. For the Pinchots were not at all surprised at the thrust and trajectory of their son's career in politics. -

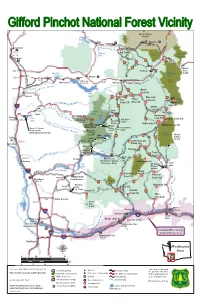

Gifford Pinchot National Forest Overview

Gifford Pinchot National Forest Vicinity ST507 Mount Rainier 14,410' Alder 7 Lake ST Glacier Elbe View Paradise !] ST123 Ashford !] ST706 ST5 Centralia !] !9 Exit 81 Mineral Big Creek William O. Exit 79 Lake CG Tatoosh Douglas Chehalis La Wis 52 !9 !] 9 Wis CG 985 984 47 9 ¤£12 White Exit 71 Packwood!] Pass 508 ST Mayfield Packwood 4,500' Lake Lake Exit 68 Salkum Morton !] ¤£12 !\ Cowlitz Valley Goat Riffe Lake £12 !@ Rocks Mossyrock Overlook ¤ Randle Ranger Station Exit 63 923 North Riffe 25 Fork CG 505 9 !9 Toledo ST Lake 76 !9 926 !9 9 Blue Lake 21 Tower 9 Iron Creek CG !9Walupt Creek CG Rock CG !9 Walupt Lake Lake CG ¨¦§5 925 Adams ST504 956 Bear Fork CG ST504 Coldwater Lake Meadow !9 Toutle Spirit 999 Horseshoe !] !\ Castle Silver !\ Lake Lake CG !9 Elk Pass 923 Killen Creek CG Rock Exit 49 Lake Elk Rock !9 Cascade 4,075' !9 3,760' !@ Peaks Olallie Lake CG !9 Johnston Ridge Windy Takhlakh Lake CG Observatory Mount St. Helens Ridge !\ Clearwater Visitor Center Mount St. 4,170' 3,200' Helens Mount (Washington State Parks) Lava 8,328' Mount Ape Canyon 925 9908 Adams Kelso Canyon 923 Adams Climber's 12,276' Exit 39 Bivouac !9 Lower Falls CG Longview & Day Use Ape Cave !9 924 Tillicum CG Trail of Swift Two Forests Reservoir Trout 988 !] 30 Creek CG McClellan 9 Exit 32 !9 Cougar Pine Creek !\ !9 Kalama Information Station Cultus Creek CG (Summers Only) Trout 503 Yale Mt.Adams ST Indian Lake Lake Ranger !@ Heaven Station 5 Lake Merwin Goose ¨¦§ Paradise !9 !9 Lake CG Peterson !@ Creek CG !9 !] Amboy MSHNVM Prairie CG ST141 Woodland Headquarters Trapper Exit 21 54 60 9 Creek 9 Moulton Oklahoma CG Yacolt Falls Beaver CG !9 Co. -

The Pinchots and the Greatest Good: How One Family Improved Social Justice and Civil Rights in America

The Pinchots and The Greatest Good: How One Family Improved Social Justice and Civil Rights in America The Pinchot family women; supported the arts; founded Liberties Bureau, a group of lawyers who has a long- and supported civil rights organizations; offered pro bono defense of cases that standing goal of campaigned tirelessly for the rights of protected basic civil liberties such as free conservation, workers, women, and children; and speech, free press, peaceful assembly, civil rights, much more. Few wealthy families of the liberty of conscience, and freedom from and social nineteenth century can point with pride search and seizure. The Little Civil justice. to such dedicated efforts on behalf of the Liberties Bureau eventually became the Gifford less fortunate. American Civil Liberties Union. Amos Pinchot was The U.S. Forest Service and its partners served on its Board until his death. not just a continue to explore this family’s efforts conservationist to improve the basic human rights that Cornelia Pinchot: and a forester— we enjoy today. Grey Towers National Cornelia, Gifford he was a trust Historic Site, Pinchot’s ancestral home Pinchot’s wife, buster, fearless Gifford Pinchot in Milford, PA, continues to deliver was a suffragette explorer, and a public programs and interpretive tours who helped get proponent of public electric power. He to thousands of visitors annually. women the fought the corruption in which the rich right to vote. and powerful dominated the agenda of These Pinchot family members continue She worked government. to inspire us and our visitors: tirelessly for Pinchot is known for reforming how Amos Pinchot: public good, forests in the United States were At the risk of helping to put managed and developed and for alienating himself an end to child advocating the conservation of the from his family labor, taking a stand Nation’s forest reserves through planned and his niche in against low pay Cornelia Pinchot use and renewal. -

2010 PEC 40 Year Anniversary

CONSERVATION THROUGH COOPERATION PCECoSntatffeanndtOs ffices . 2 PEC Board of Directors . 3 Honorary Hon. Edward G. Rendell Anniversary Governor About The Pennsylvania Committee Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Environmental Council . 5 Hon. Mark Schweiker . Former Governor Building on a Proud Past 7 Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Don Welsh – President, Hon. Tom Ridge Pennsylvania Environmental Council Former Governor At Work Across Commonwealth of Pennsylvania the Commonwealth . 9 Hon. Dick Thornburgh Former Governor Tony Bartolomeo – Chairman of the Board, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Pennsylvania Environmental Council Hon. John Hanger PEC at 40 . 10 Secretary Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection From Humble Beginnings: A look back at the Pennsylvania Hon. Kathleen A. McGinty Environmental Council’s first forty years Former Secretary Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection A Commitment to Advocacy . 17 Hon. David E. Hess Former Secretary PEC Leadership Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection Through the Years . 18 Hon. James M. Seif Former Secretary 40 Under 40 . 20 Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection The Green Generation Has Come of Age! Hon. Arthur A. Davis . Former Secretary 40 Below! 36 Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources Meet PEC’s Own Version of the “Under 40” Crowd Hon. Nicholas DeBenedictis Shutterbugs . 49 Former Secretary Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources PEC’s Photo Contest Showcases Amateur Hon. Peter S. Duncan Talent…and Spectacular Results! Former Secretary At Dominion, our dedication to a healthy clean up streams and parks, and assist Beyond 40 . 76 Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources ecosystem goes well beyond our financial established conservation groups. Environmental investment in science and technology. It also stewardship is something that runs throughout Looking Forward Hon. -

1 9/98 Rev. HISTORIC CONTEXT for TRANSPORTATION NETWORKS

9/98 rev. HISTORIC CONTEXT FOR TRANSPORTATION NETWORKS IN PENNSYLVANIA Introduction To assist with establishing the significance of the historical background of bridge building in Pennsylvania, it is important to identify and understand the historic contexts associated with the resources. Bridges do not stand in isolation, historically or physically; they embody events and trends that need to be considered when evaluating their individual or collective historical significance. Historic contexts organize historic properties in terms of theme, place, and time, and only within a historic context can what is significant “be determined in relationship to the historic development from which it emerged and in relationship to a group of similar associated properties” (National Register Bulletin 16, 1986: 6-7). In order to evaluate the National Register eligibility of the pre-1956 bridge population in Pennsylvania historic contexts have been researched and prepared twofold: one on the history of transportation networks in Pennsylvania, and the second on the application of bridge technology within the state. Both contexts address transportation issues from the earliest days of settlement to the 1950s, and both set the bridges within the national, state, and local contexts. The historic contexts will provide a means of evaluating each bridge’s technological significance, and its relationship to Pennsylvania’s transportation systems. Based on the historic contexts and their application to National Register criteria, each bridge in the inventory will be evaluated on its own merits with the contexts identifying the crucial distinctions of significance to pools of similar resources. 1. Overview Bridges are best understood as integral parts of transportation networks that carry people, vehicles, and materials over natural barriers such as rivers and streams, and over manmade barriers such as railroads, canals, and roads. -

Ninety Years Ago a Highborn Zealot Named Gifford Pinchot Knew More About Woodlands Than Any Man in America

! Ninety years ago a highborn zealot named Gifford Pinchot knew more about woodlands than any man in America. What he did about them changed the country we live in and helped define environmentalism. ike most public offi- freedom, and prosperity. The cials, Gov. Gifford Pin- urge was not entirely selfless; chot of Pennsylvania the acquisition and exercise of could not answer all power have gratifications to his mail personally. which Pinchot and his kind ..- __ Much of it had to be were by no means immune. left to aides, but not all of But at the forefront was a sol- these realized the character of emn and utterly earnest desire their boss. When a citizen that the lot of humanity wrote in 1931 to complain an- should be bettered by the grily about one of the gover- work of those who were nor's appointments, Pinchot equipped by circumstance, tal- was not pleased to find the ent, and training to change the following prepared for his sig- world. It had something to do nature: "I am somewhat sur- with duty and integrity and prised at the tone of your let- honesty, and if it was often ter. ... It has been my aim marred by arrogance, at its since I became Governor to se- best it was just as often lect the best possible person touched by compassion. for each position .... I hope And the world, in fact, was time will convince you how changed. greatly you have erred." The governor was not given have ... been a Gover- to such mewlings and forth- nor, every now and then, with composed his own letter: but I am a forester all the "Either you are totally out of time-have been, and touch with public sentiment, shall be, all my working or you decline to believe what life."GiffordPinchot made you hear ... -

Pennsylvania's Little New Deal

PENNSYLVANIA'S LITTLE NEW DEAL By RICHARD C. KELLER* A S PENNSYLVANIA entered the fourth decade of the Atwentieth century, conditions of industrial feudalism still existed within the Commonwealth. Private industrial police kept the workers docile both on and off company property; the existence of the company town frequently prevented the laborer from en- jo)inlg his leisure hours free from the watchful eye of his economic masters; women worked up to 54 and fourteen-year-old children lip to 51 hours per week for incredibly low pay; union labor received few rights and little protection from legislatures sub- inissive to the industrial interests.' These same interests dominated the political life of the Key- stone State. The Republican political machines of Simon Cameron, Matthew Quay, and Boies Penrose, allied with the barons of industrvy had controlled the state since the Civil War, but the leath of Senator Penrose on the last day of 1921 resulted in a struggle for control, since he had trained no successor. Three centers of power now emerged in Pennsylvania. In Philadelphia the Vare brothers had built a political machine through an alliance with banking and industrial interests, including W. W. Atter- burr of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and they hoped to win control of the state.2 Outside the two largest cities of the Commonwealth, the strongest figure in the Republican party was Joseph R. Grundy, who was, in the words of Penrose, "the best money collector and the worst politician since Julius Caesar."' His position as head of Dr.l Keller teaches history and government at Millersville State College.