Thesisndanga.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Indigenous Constitutional System in a Changing South Africa Digby S Koyana Adjunct Professor, Nelson R Mandela School of Law, University of Fort Hare

The Indigenous Constitutional System in a Changing South Africa Digby S Koyana Adjunct Professor, Nelson R Mandela School of Law, University of Fort Hare 1. MAIN FEATURES OF THE INDIGENOUS CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM In the African scenario the state comprises a hierarchy of component jural communities1. In hierarchical order, from the most comprehensive to the smallest, the jural communities are: the empire, the federation of tribes, the tribe, the district or section and the ward. The most common and simplest structure found amongst many peoples was the tribe, which consisted of a number of wards. The comprehensive jural community could be enlarged by the addition of tribes or tribal segments through conquest or voluntary subjugation. It is this way that empires, such as that of Shaka in Natal, were founded2. In such cases, the supreme figure of authority would be the king, and those at the head of the tribes, the chiefs, would be accountable to him. Junior chiefs in charge of wards would in turn be accountable to the chief, and there would naturally be yet more junior “officials”, relatives of the chief of the tribe, who would be in charge of the wards. The tribe itself has been described as “a community or collection of Natives forming a political and social organisation under the government, control and leadership of a chief who is the centre of the national or tribal life”3. The next question relates to the position of the chief as ruler in indigenous constitutional law. In principle the ruler was always a man. There are exceptions such as among the Lobedu tribe, where the ruler has regularly been a woman since 18004. -

The Legacy of Inkosi Albert John Luthuli's Christian-Centred Political

Faith and politics in the context of struggle: the legacy of Inkosi Albert John Luthuli’s Christian-centred political leadership Simangaliso Kumalo Ministry, Education & Governance Programme, School of Religion and Theology, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa Abstract Albert John Mvumbi Luthuli, a Zulu Inkosi and former President-General of the African National Congress (ANC) and a lay-preacher in the United Congregational Church of Southern Africa (UCCSA) is a significant figure as he represents the last generation of ANC presidents who were opposed to violence in their execution of the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. He attributed his opposition to violence to his Christian faith and theology. As a result he is remembered as a peace-maker, a reputation that earned him the honour of being the first African to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Also central to Luthuli’s leadership of the ANC and his people at Groutville was democratic values of leadership where the voices of people mattered including those of the youth and women and his teaching on non-violence, much of which is shaped by his Christian faith and theology. This article seeks to examine Luthuli’s legacy as a leader who used peaceful means not only to resist apartheid but also to execute his duties both in the party and the community. The study is a contribution to the struggle of maintaining peace in the political sphere in South Africa which is marked by inter and intra party violence. The aim is to examine Luthuli’s legacy for lessons that can be used in a democratic South Africa. -

A Handbook for Transnational Samoan Matai (Chiefs)

A HANDBOOK FOR TRANSNATIONAL SAMOAN MATAI (CHIEFS) TUSIFAITAU O MATAI FAFO O SAMOA Editors LUPEMATASILA MISATAUVEVE MELANI ANAE SEUGALUPEMAALII INGRID PETERSON A HANDBOOK FOR TRANSNATIONAL SAMOAN MATAI (CHIEFS) TUSIFAITAU O MATAI FAFO O SAMOA Chapter Editors Seulupe Dr Falaniko Tominiko Muliagatele Vavao Fetui Malepeai Ieti Lima COVER PAGE Samoan matai protestors outside New Zealand Parliament. On 28 March 2003, this group of performers were amongst the estimated 3,000 Samoans, including hundreds of transnational matai, who protested against the Citizenship [Western Samoa] Act 1982 outside the New Zealand Parliament in Wellington. They presented a petition signed by around 100,000 people calling for its repeal (NZ Herald 28 March 2003. Photo by Mark Mitchell). Macmillan Brown Centre for Pacific Studies, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch, New Zealand Website: https://www.canterbury.ac.nz/mbc/ ISBN: 978-0-473-53063-1 Copyright © 2020 Macmillan Brown Center for Pacific Studies, University of Canterbury All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information retrieval system, without permission from the publisher. No royalties are paid on this book The opinions expressed and the conclusions drawn in this book are solely those of the writer. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Macmillan Brown Centre for Pacific Studies Editing & Graphic Designing Dr Rosemarie Martin-Neuninger Published by MacMillan Brown Centre for Pacific Studies, University of Canterbury DEDICATION A Tribute This book is dedicated to one of the symposium participants, Tuifa'asisina Eseta Motofoua Iosia, who passed away on 8 April 2020. -

I~S~Id 5Y September 1, 1952

I~s~id5y vT&- P.,L?~C07. ,T , SCI3JCX E3ii33 ~ictiond-. +oecc.rch Councii iKcisliingtor, D. C. September 1, 1952 TFBLE OF CONTRiTS Profwe ........................................................ iii ;~C!QIOV~C.dgeine~.tr; ..............+................................ iii Introduc:tioil: Lmd Teriure ................................. .. .. 1 Piiysiczl Description ........................................... 2 Lad Use ....................................................... 3 fiieciiimk? of Divisioll of Copm Shme ........................... 4 Deviations fzom thz Getlord Pc-tterr. ............................ 4 Inheritmcc 2,-ttern ..........................................mo 5 P?.trilined Usufruct ilights .................................... 6 Adoptive Rights ..........................................o.... 7 Usufruct ?.ights kcquiced ky l~ilinri'iage .......................... 8 I.!ills .......................................................... 8 Xen'mls ........................................................ 9 bhclavos ....................................................... 9 Reef 3iights .................................................... 11 Fishing Rights ................................................ 12 Game Rzserve:; .................................................. 12 Indigenous Attihdzs Tomrd Lad .............................. 13 Conce?ts of L2nd h'wrhlp ...................................... 13 Cntegoriss 3f Lmd ... 15 Bwij in A3e - fmoimje - D'ficied Lsrd ........................... 16 Conclusion ...........................................o........ -

European Colonialism in Cameroon and Its Aftermath, with Special Reference to the Southern Cameroon, 1884-2014

EUROPEAN COLONIALISM IN CAMEROON AND ITS AFTERMATH, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE SOUTHERN CAMEROON, 1884-2014 BY WONGBI GEORGE AGIME P13ARHS8001 BEING A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, NIGERIA, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS (MA) DEGREE IN HISTORY SUPERVISOR PROFESSOR SULE MOHAMMED DR. JOHN OLA AGI NOVEMBER, 2016 i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this Dissertation titled: European Colonialism in Cameroon and its Aftermath, with Special Reference to the Southern Cameroon, 1884-2014, was written by me. It has not been submitted previously for the award of Higher Degree in any institution of learning. All quotations and sources of information cited in the course of this work have been acknowledged by means of reference. _________________________ ______________________ Wongbi George Agime Date ii CERTIFICATION This dissertation titled: European Colonialism in Cameroon and its Aftermath, with Special Reference to the Southern Cameroon, 1884-2014, was read and approved as meeting the requirements of the School of Post-graduate Studies, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, for the award of Master of Arts (MA) degree in History. _________________________ ________________________ Prof. Sule Mohammed Date Supervisor _________________________ ________________________ Dr. John O. Agi Date Supervisor _________________________ ________________________ Prof. Sule Mohammed Date Head of Department _________________________ ________________________ Prof .Sadiq Zubairu Abubakar Date Dean, School of Post Graduate Studies, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to God Almighty for His love, kindness and goodness to me and to the memory of Reverend Sister Angeline Bongsui who passed away in Brixen, in July, 2012. -

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone Tristan Reed1 James A. Robinson2 July 15, 2013 1Harvard University, Department of Economics, Littauer Center, 1805 Cambridge Street, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. 2Harvard University, Department of Government, IQSS, 1737 Cambridge Street., N309, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract1 In this manuscript, a companion to Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson (2013), we provide a detailed history of Paramount Chieftaincies of Sierra Leone. British colonialism transformed society in the country in 1896 by empowering a set of Paramount Chiefs as the sole authority of local government in the newly created Sierra Leone Protectorate. Only individuals from the designated \ruling families" of a chieftaincy are eligible to become Paramount Chiefs. In 2011, we conducted a survey in of \encyclopedias" (the name given in Sierra Leone to elders who preserve the oral history of the chieftaincy) and the elders in all of the ruling families of all 149 chieftaincies. Contemporary chiefs are current up to May 2011. We used the survey to re- construct the history of the chieftaincy, and each family for as far back as our informants could recall. We then used archives of the Sierra Leone National Archive at Fourah Bay College, as well as Provincial Secretary archives in Kenema, the National Archives in London and available secondary sources to cross-check the results of our survey whenever possible. We are the first to our knowledge to have constructed a comprehensive history of the chieftaincy in Sierra Leone. 1Oral history surveys were conducted by Mohammed C. Bah, Alimamy Bangura, Alieu K. -

Cameroon Version 4 Clean#2

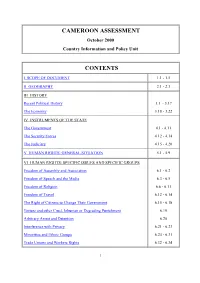

CAMEROON ASSESSMENT October 2000 Country Information and Policy Unit CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.3 III HISTORY Recent Political History 3.1 - 3.17 The Economy 3.18 - 3.22 IV INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE The Government 4.1 - 4.11 The Security Forces 4.12 - 4.14 The Judiciary 4.15 - 4.20 V HUMAN RIGHTS: GENERAL SITUATION 5.1 - 5.9 VI HUMAN RIGHTS: SPECIFIC ISSUES AND SPECIFIC GROUPS Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.1 - 6.2 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.3 - 6.5 Freedom of Religion 6.6 - 6.11 Freedom of Travel 6.12 - 6.14 The Right of Citizens to Change Their Government 6.15 - 6.18 Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Punishment 6.19 Arbitrary Arrest and Detention 6.20 Interference with Privacy 6.21 - 6.23 Minorities and Ethnic Groups 6.24 - 6.31 Trade Unions and Workers Rights 6.32 - 6.34 1 Human Rights Groups 6.35 - 6.36 Women 6.36 - 6.41 Children 6.42 - 6.45 Treatment of Refugees 6.46 - 6.48 ANNEX A: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS Pages 19 - 22 ANNEX B: PROMINENT PEOPLE Page 23 ANNEX C: CHRONOLOGY Pages 24 - 27 ANNEX D: BIBLIOGRAPHY Pages 28 - 29 I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process. -

Honor, Violence, Resistance and Conscription in Colonial Cameroon During the First World War

Soldiers of their Own: Honor, Violence, Resistance and Conscription in Colonial Cameroon during the First World War by George Ndakwena Njung A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Rudolph (Butch) Ware III, Chair Professor Joshua Cole Associate Professor Michelle R. Moyd, Indiana University Professor Martin Murray © George Ndakwena Njung 2016 Dedication My mom, Fientih Kuoh, who never went to school; My wife, Esther; My kids, Kelsy, Michelle and George Jr. ii Acknowledgments When in the fall of 2011 I started the doctoral program in history at Michigan, I had a personal commitment and determination to finish in five years. I wanted to accomplish in reality a dream that began since 1995 when I first set foot in a university classroom for my undergraduate studies. I have met and interacted with many people along this journey, and without the support and collaboration of these individuals, my dream would be in abeyance. Of course, I can write ten pages here and still not be able to acknowledge all those individuals who are an integral part of my success story. But, the disservice of trying to acknowledge everybody and end up omitting some names is greater than the one of electing to acknowledge only a few by name. Those whose names are omitted must forgive my short memory and parsimony with words and names. To begin with, Professors Emmanuel Konde, Nicodemus Awasom, Drs Canute Ngwa, Mbu Ettangondop (deceased), wrote me outstanding references for my Ph.D. -

ECFG-Cameroon-Apr-19.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to help prepare you for deployment to culturally complex environments and successfully achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information it contains will help you understand the decisive cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain necessary skills to achieve ECFG mission success. The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1: Introduces Cameroon “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2: Presents “Culture Specific” Cameroon, focusing on unique cultural features of Cameroonian society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

EMERGENT MASCULINITIES: the GENDERED STRUGGLE for POWER in SOUTHEASTERN NIGERIA, 1850-1920 by Leonard Ndubueze Mbah a DISSERTAT

EMERGENT MASCULINITIES: THE GENDERED STRUGGLE FOR POWER IN SOUTHEASTERN NIGERIA, 1850-1920 By Leonard Ndubueze Mbah A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History – Doctor of Philosophy 2013 ABSTRACT EMERGENT MASCULINITIES: THE GENDERED STRUGGLE FOR POWER IN SOUTHEASTERN NIGERIA, 1850-1920 By Leonard Ndubueze Mbah This dissertation uses oral history, written sources, and emic interpretations of material culture and rituals to explore the impact of changes in gender constructions on the historical processes of socio-political transformation among the Ohafia-Igbo of southeastern Nigeria between 1850 and 1920. Centering Ohafia-Igbo men and women as innovative historical actors, this dissertation examines the gendered impact of Ohafia-Igbo engagements with the Atlantic and domestic slave trade, legitimate commerce, British colonialism, Scottish Christian missionary evangelism, and Western education in the 19th and 20th centuries. It argues that the struggles for social mobility, economic and political power between and among men and women shaped dynamic constructions of gender identities in this West African society, and defined changes in lineage ideologies, and the borrowing and adaptation of new political institutions. It concludes that competitive performances of masculinity and political power by Ohafia men and women underlines the dramatic shift from a pre-colonial period characterized by female bread- winners and more powerful and effective female socio-political institutions, to a colonial period of male socio-political domination in southeastern Nigeria. DEDICATION To the memory of my father, late Chief Ndubueze C. Mbah, my mother, Mrs. Janet Mbah, my teachers and Ohafia-Igbo men and women, whose forbearance made this study a reality. -

Of Southern Africa

of Southern Africa Busutoland, liechuanaland Protectorate, Swaziland. by SIR CHARLES DUNDAS AND Dr. HUGH ASHTON Price 7s. 6d. Net. THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Cape Town Durban Joh.imieshurg Port Elizabeth The South African Institute of Intenintional Affairs is an unofficiiil body founded in 1934 to promote through study, discussion, lectures, and public addresses .in understanding of international questions and problems. The Institute, as such, is precluded hy the terms of its Constitution from expressing an opinion un any aspect of international uffiiirs. Any opinions expressed in this publication arc not, therefore, those of the Institute. First Published 1952 For further information consult The General Secretary P.O. Box 9J7" Johannesburg South Africa rotewotd 1 I 'HE world today is in such a disturbed state that the study of -L international affairs on a global scale is of necessity extremely complex. While in its discussions the South African Institute of International Affairs is concerned with the problems of the world at large, its policy in recent years has been to limit its research to the "local" region of Africa south of the Sahara. In dealing with the Union's relations with other African territories and particularly with its near neighbours, the Institute has found among South Africans surprising ignorance of the facts relating to these territories. It is obviously important to have factual information regarding the relations between one's country and other territories and in July, 1946, the Institute published a pamphlet on South-West Africa. At that time important discussions were taking place in UNO and the Institute received many expressions of appreciation of the value of that pamphlet in setting out the significant facts. -

The African Patriots, the Story of the African National Congress of South Africa

The African patriots, the story of the African National Congress of South Africa http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp3b10002 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The African patriots, the story of the African National Congress of South Africa Author/Creator Benson, Mary Publisher Faber and Faber (London) Date 1963 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Source Northwestern University Libraries, Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, 968 B474a Description This book is a history of the African National Congress and many of the battles it experienced.