Homeric Games at Ancient St. Andrews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Forms Assembled in the Light” Week One: Early Medieval Art

ART HISTORY Journey Through a Thousand Years “Forms Assembled in the Light” Week One: Early Medieval Art The Craftsmen Who Saved Civilisation - The Civilisation that Survived – Controversy Over Images – Decoding Anglo-Saxon Art - Basilicas - Illuminated Manuscripts – In Search of Three Dimensions – From the Vaults: The Lindau Gospels – Ottonian Art – The Bernward Doors - An Introduction to the Bestiary, Book of Beasts in the Medieval World - The painted crypt of San Isidoro at León, Spain By Megginede - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45924271 “Great nations write their autobiographies in three manuscripts[;] the book of their deeds, the book of their words, and the book of their art. Not one of these works can be understood unless we read the two others, but of the three the only trustworthy one is the last.” – Ruskin Kenneth Clark: “The Craftsmen Who Saved Civilization” From Civilisation: A Personal View (1969) People sometimes tell me they prefer barbarism to civilization. I doubt if they have given it a long enough trial. Like the people of Alexandria they are bored by civilisation; but all the evidence suggests that the boredom of barbarism is infinitely greater. Quite apart from discomforts and privations, there was no escape from it. Very restricted company, no books, no light after dark, no hope. On one side of the sea battering away, on the other the infinite stretches of the bog and the forest. A most melancholy existence, and the Anglo- Saxon poets had no illusions about it: A wise man may grasp how ghastly it shall be When all this world’s wealth standeth waste Even as now, in many places over the earth, Walls stand windbeaten, Heavy with hoar frost; ruined habitations… The maker of men has so marred this dwelling That human laughter is not heard about it, And idle stand these old giant works. -

“Northern Touch” - the Rascals

“Northern Touch” - The Rascals [Hook: Kardinal Offishall] Yo... We notorious; ain't nobody can bang with us Rascalz, Checkmate, Kardinal and Thrust Choclair coming down with that Northern touch, yo... Why you people wanna bang with us Ain't nobody can hang with us Rascals, Checkmate, Kardinal and Thrust Choclair coming down with the Northern touch Tiggy touch, biggie baby... [Verse 1: Rascalz] Check the lingo we spread through the atmosphere So distinctive no other style comes near So when you hear you've got to peer over the ledge to get a glance To know who is the man with the talents Flipping my words like my body on the apparatus Sky's the limit so I'm bound to break through the stratus With these rhymes that are classics Forget the fads and the fashions Step in and make on the microphone Aiyo world domination is the base of foundation No time wasting Fire walk we trail blazing Burn to the next destination Flexing on this world exploration Teamed with the best in the nation Yes and who that be Custom design fine rhymes into salary All the way from t-dot to the van city all stars Rude boys freak you like a fantasy Word up... [Interlude: Choclair] Yes from the northwest And the t-dot, o-dizot check [Verse 2: Choclair] I like chillin, Monday Night Raw watching Me and Dan-E-O at the SkyDome when it's in town My peoples know I just be regular So haters start dissin But steady reciting my lyrics All with my dick in they mouth They swallowin Talking bout they need oxygen People need to know Choclair Don't move in no slow-mo Into women like -

Inferring Theme and Decoding Figurative Language in Hip

Northside Hip Hop Archive Curriculum Resource Guide: English, Grade 10, Academic/Applied (ENG2D/P) – Lesson 3 Lesson Title The Message: Inferring Theme and Decoding Figurative Language in Hip Hop Expectations: Learning Goals Assessment Make inferences about Lyrical Spotlight MEDIA: Interpreting Messages 1.2 interpret media texts, including theme increasingly complex texts, identifying and explaining the overt and Identify and explain Analyze the Bars implied messages they convey metaphor and simile Materials Audio: k-os’ “ELEctrik HeaT - the SeekwiLL” MEDIA: Critical Literacy 1.5 identify the perspectives and/or biases Handout: k-os’ “ELEctrik HeaT - the SeekwiLL” lyrics evident in media texts, including increasingly complex texts, and Highlighters comment on any questions they may raise about beliefs, values, identity Summative Task: Lyrical Spotlight Reflection: Look Back exit slips LCD Projector, Laptop and Internet access READING: Extending Understanding of Texts 1.5 extend understanding of both simple and complex texts by making connections between the ideas in them and personal knowledge, experience, and insights; other texts; and the world around them Analyze the Bars Assessment The teacher briefly reviews the concept of metaphor and simile. The teacher discusses the Opportunities idea of theme as a human understanding that emerges from a text, explaining how song content and style supports this understanding. Students listen to the song “ELEctrik HeaT Assessment - the SeekwiLL” by k-Os (www.nshharchive.ca/curriculum/english.html). They examine a FOR Minds OnMinds written copy of the lyrics in small groups. Using highlighters, they look for metaphors, Learning: Time: 20 similes and rhyme. Each group chooses an example of figurative language and writes it on Group lyrics chart paper/the board for all to read. -

“The Mic Is My Piece”: Canadian Rap, the Gendered “Cool Pose,” and Music Industry Racialization and Regulation Francesca D’Amico

Document generated on 09/26/2021 3:33 p.m. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada “The Mic Is My Piece”: Canadian Rap, the Gendered “Cool Pose,” and Music Industry Racialization and Regulation Francesca D’Amico Volume 26, Number 1, 2015 Article abstract Over the course of the 1980s and 1990s, Black Canadian Rap artists, many of URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1037204ar whom are the children of Caribbean-born immigrants to Canada, employed the DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1037204ar hyper-racialized and hyper-gendered “Cool Pose” as oppositional politics to intervene in a conversation about citizenship, space, and anti-blackness. See table of contents Drawing from local and trans-local imaginings and practices, Black Canadian rappers created counter-narratives intended to confront their own sense of exclusion from a nation that has consistently imagined itself as White and Publisher(s) rendered the Black presence hyper-(in)visible. Despite a nationwide policy of sameness (multiculturalism), Black Canadian musicians have used Rap as a The Canadian Historical Association / La Société historique du Canada discursive and dialogical space to disrupt the project of Black Canadian erasure from the national imagination. These efforts provided Black youth with the ISSN critically important platform to critique the limitations of multiculturalism, write Black Canadian stories into the larger framework of the nation state, and 0847-4478 (print) remind audiences of the deeply masculinized and racialized nature of 1712-6274 (digital) Canadian iconography. And yet, even as they engaged in these oppositional politics, rappers have consistently encountered exclusionary practices at the Explore this journal hands of the state that have made it increasingly difficult to sustain a Black music infrastructure and spotlight Canadian Rap’s political and cultural intervention. -

Speaking up for Education

OCTOBER 2010 VOLUME 13 - NUMBER 10 FREE Speaking up for education Elders Rose Atimoyoo and Gladys Wapass Greyeyes checkoutMakingTheConnection.Gladyscommented thatifsheknewthemediaweretakingpictures,shewould havebroughtherbathingsuit! (PhotobyJohnLagimodiere) CELEBRATING LITERACY Prolific author Freda Ahenakew joined in a celebration of Cree literacy. - Page 3 THEPERFECTROLE ActorAdamBeachhashadhis strugglesandnowhe’shappyto beplayingarolehewasbornto perform. - Page 12 GAMING DOLLARS Language seen as foundation of culture WilmaIsbisterbelievesshehas By John Lagimodiere important to both of them. thebestjobinSaskatchewan. Of Eagle Feather News “My mother taught me I have two ears to listen with, And she’s got $2.6 million to and eyes to see, that’s how I learned,” said Elder Gladys back her claim. - Page13 n amazing collection of Elders shared their stories and thoughts on Cree education practices Wapass Greyeyes who took part in the interviews several with a university researcher over 15 years ago. years ago. A CLEAR PATH Those thoughts were the basis of a study that turned into “You listened, looked and learned.And today the YvonneSt.Germainehasturned Aa Master’s thesis titled The Foundations of Cree difference is our children go to school and learn to read her life around thanks to music Education by Gordon Lobe. and write. That’s one way to pass on the teachings. and a spiritual re-birth. The Office of the Treaty Commissioner and Gordon “I would appreciate it if the stories are written exactly - Page 16 Lobe have now published a logical and practical book the way we tell them. It is difficult because you can’t for the education system by translating those Elders’ literally translate Cree to English. -

Small Business Celebrate Small Business Month with Special Programs and Workshops

PROGRAMS AND EVENTS AT YOUR LIBRARY SEPTEMBER — DECEMBER 2012 Small Business Celebrate Small Business Month with special programs and workshops. Meet CBC Dragons’ Den Jim Treliving, pages 3 & 17 Toronto Book Awards Meet this year’s finalists, page 11 At the Bram & Bluma Appel Salon Martin Amis, Carlos Ruis Zafon, Val McDermid, David Frum, Emma Donoghue, page 6 Photo: A small business class in one of the library’s Learning Centres. What’s New in our collections NEW ADULT FICTION The Chemistry of Into the Dreaming The Family The Columbus Truth Like the Sun Tears Karen Marie Corleone Affair Jim Lynch Peter Carey Moning Edward Falco Steve Berry NEW TEEN FICTION Lexapros and Cons Pilgrims Don’t Monster High 4: Taken at Dusk Black Dawn: Aaron Karo Wear Pink Back and Deader C.C. Hunter The Morganville Stephanie Kate Than Ever Vampires Strohm Lisi Harrison Rachel Caine NEW CHILDREN’s fictioN Meerkat Madness: A Confusion of Theodore Boone: The Legend of Baby Bear Sees Blue Flying High Princes The Accused Diamond Lil: Ashley Wolff Ian Whybrow Garth Nix John Grisham A J.J. Tully Mystery Doreen Cronin Visit torontopubliclibrary.ca for more new books, music and movies. Reserve your selections online and arrange to pick them up at any branch. IN THIS ISSUE 2 About Toronto Public Library 3 Small Business Month Published by Toronto Public Library 789 Yonge Street, Toronto, Ontario M4W 2G8 7 Author Talks & Lectures 416-393-7000 • torontopubliclibrary.ca 14 Book Clubs & Writers Groups 17 Business, Legal & Finance Toronto Public Library Board The Toronto Public Library Board meets 22 Career & Job Search Help monthly at 6 pm, September through 23 Computer & Library Training June, at the Toronto Reference Library, 789 Yonge Street, Toronto. -

OUR YELLOWKNIFE the Wild Doesn’T End Where the Roads Begin

TRAVEL TIPS • MAPS • ACTIVITIES FREE! DISCOVER OUR YELLOWKNIFE The wild doesn’t end where the roads begin 2017 VISITORS GUIDE OLD TOWN. PILOT’S MONUMENT. WILDCAT CAfÉ. LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. FRAME LAKE TRAIL. SEE THEM ALL. If you’re visiting Yellowknife, stop by the Northern Frontier Visitors Centre Outcrop is offering visitors free use of a fleet of sturdy one-speed bicycles for touring anywhere within the city limits, any day of the week from early June until late September. The Quarry Restaurant, located at the Chateau Nova Yellowknife, delivers food and quality nothing short of exceptional. This modern steakhouse-themed restaurant is opened for breakfast, lunch and dinner and offers a large menu at really great prices. NORTHERN FRONTIER Our Quarry Lounge provides the perfect atmosphere to meet for drinks, enjoy nightly food specials or finish the day VISITORS CENTRE with a nice glass of vino. 867.873.4262 visityellowknife.com CLIENT: Client Name VERSION: A REVISION: 1 DATE: Dec / 22 / 16 TIME: DOCKET #: 0000-A000 SIZE: 5.25” x 8.5” (with full bleed 0.125”) (Full page) COLOUR: CMYK DESIGNER: BC PUBLICATION: Visitor’s Guide, Year UP HERE PUBLISHING LTD. / Suite 800 / 4920-52 Street / Yellowknife / Northwest Territories / Canada / X1A 3T1 / T. 867-766-6710 / F. 867-873-9876 / www.uphere.ca The City of Yellowknife WELCOMES YOU! Discover Yellowknife is a cooperative effort from our own City staff, the friendly tourism staff at the Northern Fron- tier Visitor Centre and the team at Up Here Publishing. Yellowknife’s unique location is the perfect start for an unforgettable experience. -

The Americans with Disabilities Act and Accessible Transportation: Challenges and Opportunities

S. HRG. 112–880 THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT AND ACCESSIBLE TRANSPORTATION: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES HEARING OF THE COMMITTEE ON HEALTH, EDUCATION, LABOR, AND PENSIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON EXAMINING THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT AND ACCESSIBLE TRANSPORTATION, FOCUSING ON CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES NOVEMBER 17, 2011 Printed for the use of the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 87–946 PDF WASHINGTON : 2014 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HEALTH, EDUCATION, LABOR, AND PENSIONS TOM HARKIN, Iowa, Chairman BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico LAMAR ALEXANDER, Tennessee PATTY MURRAY, Washington RICHARD BURR, North Carolina BERNARD SANDERS (I), Vermont JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia ROBERT P. CASEY, JR., Pennsylvania RAND PAUL, Kentucky KAY R. HAGAN, North Carolina ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona AL FRANKEN, Minnesota PAT ROBERTS, Kansas MICHAEL F. BENNET, Colorado LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska SHELDON WHITEHOUSE, Rhode Island MARK KIRK, Illinois RICHARD BLUMENTHAL, Connecticut DANIEL E. SMITH, Staff Director PAMELA SMITH, Deputy Staff Director FRANK MACCHIAROLA, Republican Staff Director and Chief Counsel (II) CONTENTS STATEMENTS THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2011 Page COMMITTEE MEMBERS Harkin, Hon. Tom, Chairman, Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, opening statement ............................................................................... 1 WITNESSES Capozzi, David M., Executive Director, U.S. -

Thainess.Pdf

30 Resort Destinations with the Souls of Thais Mae Hong Son Chiang Mai LAOS Loei Nong Khai Sukhothai MYANMAR THAILAND Nakhon Ratchasima Ubon Ratchathani Kanchanaburi Bangkok Chon Buri Andaman CAMBODIA “เขาเมืองตาหลิ่ว ตองหลิ่วตาตาม” Sea Rayong When in Thailand do as the Thais do Trat Prachuap Khiri Khan Gulf of Thailand Phang nga Surat Nakhon Si Thani Thammarat Th e Kingdom Of Th ailand Ko Phuket Thailand is situated just north of the equator in the Trang heart of South-East Asia. The country is the third largest in the region and its shape resembles an axe, the handle being the long peninsula to the south. It is a place that can be visited at any time of the year with a variety of ethnic cultures and traditions and a wealth of natural attractions. MALAYSIA PREFACE A small, wooden boat stacked high with pomeloes, mangoes, bananas, and jackfruit fresh from the orchards floats slowly down a canal. Monkeys play in the palm trees while farmers pick their homegrown vegetables to sell at the market. Others are preparing to harvest the golden rice almost ready in the paddies. The smell of cooking rice means it is close to meal time. These timeless images are dreams of a way of life that has existed for a long time and continues today, of traditional knowledge and a peaceful philosophy that have stood the test of time, of wisdom passed from generation to generation. But these dreams are reality in Thailand, a country of rich cultural heritage, stunning natural attractions, and friendly, smiling people. ‘Thainess – Live and Learn the Thai Way of Life’ visits 30 resort destinations to show this heritage, beauty, and happiness that makes the magic of the traditional way of life. -

Northern Touch”: Using Hip-Hop Education to Interrupt Notions of Nationhood and Belonging

Chapter10 The “Northern Touch”: Using Hip-hop Education to Interrupt Notions of Nationhood and Belonging Francesca D’Amico-Cuthbert @hiphopscholar82 On January 29 2008, Canada’s largest school board in Toronto, Ontario voted to open an alternative school in order to pilot Afrocentric pedagogy, combat an estimated 40% drop out rate among Black teens, and establish a center for research on how to close the learning gap between Black students and their non-Black peers. Since 1995 when the province’s Royal Commission on Learning suggested that a Black-focused school might help stem these statistics, and the city’s school board reported that 40% of Caribbean-born and 32% of East-African born students in Toronto drop out of high school yearly, administrators have attempted to find strategies to address the issue. Today administrators, activists, and parents continue to argue that Canadian provincial curriculum is Eurocentric. This Eurocentricity leads school systems to overlook the heritage of Black students, with teaching failing to reflect racial diversity in their classrooms and to productively interact with Black students. During the 2008 proceedings, community leader Murphy Brown argued that due to the failure to incorporate even the most basic of African Canadian history instruction, Black youth are being pushed out of the system in what she calls a “school-to-jail-pipeline” (Brown & Popplewell, 2008). Following the 2008 proceedings, Toronto education groups, both institutional and community-based, discovered that hip-hop curriculum retained the capacity to combat this exclusionary education model. Specifically, educators have recognized that hip-hop can alter educational outcomes by creating a transformative educational space where youth can become critically conscious of self as well as the effects of historical and contemporaneous structural inequities (Akom, 2009). -

Black Canadian Writing Term

THE UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG ENGL-3709.3-002 Topics in Canadian Literature and Culture: Black Canadian Writing Term: Winter 2013 Professor: Dr. Candida Rifkind Time: Tues. & Thurs. 2:30-3:45pm Office: 2A38 Room: 4BC57 Phone: 204-786-9198 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. & Thurs. 1:00-2:00pm or by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION This course introduces students to the vibrant and diverse field of Black Canadian writing through fiction (novels and short stories), drama, poetry, and popular culture. Most of the course texts appeared after 1990 and so we will focus on contemporary practices and innovations in such literary forms as the historical novel, urban fiction, long poem, poetry cycle, and drama as well as the performance cultures of spoken word, jazz, dub, rap, and djing/turntablism. In addition to the creative texts, this course will introduce students to key concepts in critical race theory and Black studies through criticism and theory that contextualizes these Canadian writers in the flows and tides of the larger Black Atlantic. REQUIRED TEXTS (in order of reading) The following books have been ordered for the course through Mondragon (91 Albert Street in the Exchange District). Where possible, they have also been placed on 4hr reserve in the UW Library. They are listed in order of reading. Other required readings are available through the Nexus site for the course (see attached Reading Schedule). Hill, Lawrence. The Book of Negroes . Toronto: HarperCollins, 2007. Print. Clarke, George Elliott. Whylah Falls . 1990. Kentville, NS: Gaspereau, 2010. Print. Sears, Djanet. Harlem Duet . Winnipeg, MB: Scirocco Drama, 1998. -

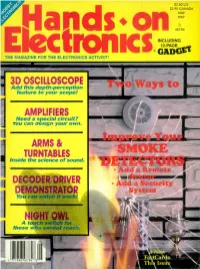

Add a Security System

$2.50 U.S. $2.95 CANADA MAY 1987 Handson 48784 SINCLUDING 12 -PAGE R GAJX ElectionTHE MAG AZINE FOR THE ELECTRONICS ACTIVIST! 3D OSCILLOSCOPF Add this depth -perception I feature to your scope! AMPLIFIERS Need a special circuit? J You can design your own. J ARMS & TURNTABLES IlInside the science of sound. Add a Remote (m DECODERDRI VER Add a Security DEMONSTRATOR System You can watch it work! NIGHT OWL A touch switch for those who cannot reach. 05 - o 71 896 48784III8 :0' IS COMING IN MAY . , . t.,'. ., ' t`'4.!.'. `.. aPMP°ce vNF 1Pe ezáa NpÓM N v' vOpÉHQS Qr°oe; r ÑE FpA `etÑ`¡1ÁPP'°< Gó e use áPPN óé 1°µs N°1gau°Ñt. °a 1 ° Vápß e P°kt°15 An electronics revolution is in the making, but you don't have emerging technology with a solid foundation in current re- to wait until 2001 to find out how it will change your life in search and development. the 21st century. Radio -Electronics will forecast the coming And its impact will be enormous It will change the way you changes and how they will affect you in the May 1987 issue! work... me way you pink... the way you live! Created by a special editorial task force-two years in prepa- 2001 is the kind of special publishing Event that can only ration -this unique issue, 2001, takes you into the research happen once in any magazine's lifetime and it will happen laboratories of Westinghouse, Texas Instruments, Ford and to Radio -Electronics in May, 1987.