Roundtable on Governance & Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biomedical Engineering Graduate Program Background

302 Maroun Semaan Faculty of Engineering and Architecture (MSFEA) Biomedical Engineering Graduate Program Dawy, Zaher Coordinator: (Electrical & Computer Engineering, MSFEA) Jaffa, Ayad Co-coordinator: (Biochemistry & Molecular Genetics, FM) Amatoury, Jason (Biomedical Engineering, MSFEA) Daou, Arij (Biomedical Engineering, MSFEA) Darwiche, Nadine (Biochemistry & Molecular Genetics, FM) Coordinating Committee Khoueiry, Pierre Members: (Biochemistry & Molecular Genetics, FM) Khraiche, Massoud (Biomedical Engineering, MSFEA) Mhanna, Rami (Biomedical Engineering, MSFEA) Oweis, Ghanem (Mechanical Engineering, MSFEA) Background The Biomedical Engineering Graduate Program (BMEP) is a joint MSFEA and FM interdisciplinary program that offers two degrees: Master of Science (MS) in Biomedical Engineering and Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Biomedical Engineering. The BMEP is housed in the MSFEA and administered by both MSFEA and FM via a joint program coordinating committee (JPCC). The mission of the BMEP is to provide excellent education and promote innovative research enabling students to apply knowledge and approaches from the biomedical and clinical sciences in conjunction with design and quantitative principles, methods and tools from the engineering disciplines to address human health related challenges of high relevance to Lebanon, the Middle East and beyond. The program prepares its students to be leaders in their chosen areas of specialization committed to lifelong learning, critical thinking and intellectual integrity. The curricula of the -

A Cybernetics Update for Competitive Deep Learning System

OPEN ACCESS www.sciforum.net/conference/ecea-2 Conference Proceedings Paper – Entropy A Cybernetics Update for Competitive Deep Learning System Rodolfo A. Fiorini Politecnico di Milano, Department of Electronics, Information and Bioengineering (DEIB), Milano, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +039-02-2399-3350; Fax: +039-02-2399-3360. Published: 16 November 2015 Abstract: A number of recent reports in the peer-reviewed literature have discussed irreproducibility of results in biomedical research. Some of these articles suggest that the inability of independent research laboratories to replicate published results has a negative impact on the development of, and confidence in, the biomedical research enterprise. To get more resilient data and to achieve higher result reproducibility, we present an adaptive and learning system reference architecture for smart learning system interface. To get deeper inspiration, we focus our attention on mammalian brain neurophysiology. In fact, from a neurophysiological point of view, neuroscientist LeDoux finds two preferential amygdala pathways in the brain of the laboratory mouse to experience reality. Our operative proposal is to map this knowledge into a new flexible and multi-scalable system architecture. Our main idea is to use a new input node able to bind known information to the unknown one coherently. Then, unknown "environmental noise" or/and local "signal input" information can be aggregated to known "system internal control status" information, to provide a landscape of attractor points, which either fast or slow and deeper system response can computed from. In this way, ideal system interaction levels can be matched exactly to practical system modeling interaction styles, with no paradigmatic operational ambiguity and minimal information loss. -

The Elliott School of INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS

THE ELLIOtt SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS ANNUAL REPORT 2006/2007 MISSION THE MISSION OF THE ELLIOTT SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS IS: • To educate the next generation of international leaders • To conduct research and produce scholarship that advances understanding of important global issues • To engage the public and the policy community in the United States and around the world, thereby fostering international dialogue and shaping policy solutions Our mission is to create knowledge, share wisdom and inspire action to make our world a better place. A MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN recent survey of scholars ranked the Elliott School’s undergraduate and graduate programs in the top 10. Only five schools in the world were ranked this highly in A both categories. It’s an impressive club. It’s also an important club. The issues we study at the Elliott School—ranging from war and peace to poverty and development—affect the lives of billions of our fellow human beings. Powerful international dynamics—population growth, rising levels of resource consumption, the expansion of the global economy, mounting environmental challenges—will shape the world in the decades ahead. Wise policy and effective international cooperation will be more important than ever. At the Elliott School, the study of international affairs is not an abstract exercise. Our aim is to make our world a better place. The Elliott School is in a unique position to make a difference. Our location in the heart of Washington, DC—just steps from some of the most influential U.S., international and non- governmental organizations in the world—enriches our teaching and research, and it provides us with unmatched opportunities to engage the U.S. -

Ukraine's Domestic Affairs

No. 1 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JANUARY 7, 2001 7 2000: THE YEAR IN REVIEW on February 22, aimed to “increase the economic inde- cent of farmers leased land, according to the study, while Ukraine’s domestic affairs: pendence of the citizenry and to promote entrepreneurial another 51 percent were planning to do so. activity,” said Minister of the Economy Tyhypko. The survey produced by the IFC came at the conclu- Mr. Tyhypko, who left the government a few weeks sion of a $40 million, five-year agricultural and land the good, the bad, the ugly later over disagreements with Ms. Tymoshenko and was reform project. elected to a vacant Parliament seat in June, indicated that n the domestic front in 2000 it was a roller coast- Trouble in the energy sector the program would assure deficit-free budgets, and even er ride for Ukraine, the economy being one of the budget surpluses for Ukraine, which could lead to repay- few surprisingly steady elements in an otherwise Reform of Ukraine’s most troubled economic sector, ment of wage and debt arrears, a radical reduction in the unstable year. fuel and energy, proceeded much more turbulently and country’s debt load and a stable currency. A stated longer- The new millennium began at a high point for Ukraine. claimed at least two victims. Ms. Tymoshenko, the con- O term goal was the privatization of land and resurgence of At the end of 1999 the nation had re-elected a president troversial energy vice prime minister, was not, however, the agricultural sector. -

An Open Logic Approach to EPM

OPEN ACCESS www.sciforum.net/conference/ecea-1 Conference Proceedings Paper – Entropy An Open Logic Approach to EPM Rodolfo A. Fiorini 1,* and Piero De Giacomo 2 1 Politecnico di Milano, Department of Electronics, Information and Bioengineering, Milano, Italy; E- Mail: [email protected] 2 Dept. of Neurological and Psychiatric Sciences, Univ of Bari, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] * E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +039-02-2399-3350; Fax: +039-02-2399-3360. Received: 11 September 2014 / Accepted: 21 October 2014 / Published: 3 November 2014 Abstract: EPM is a high operative and didactic versatile tool and new application areas are envisaged continuosly. In turn, this new awareness has allowed to enlarge our panorama for neurocognitive system behaviour understanding, and to develop information conservation and regeneration systems in a numeric self-reflexive/reflective evolutive reference framework. Unfortunately, a logically closed model cannot cope with ontological uncertainty by itself; it needs a complementary logical aperture operational support extension. To achieve this goal, it is possible to use two coupled irreducible information management subsystems, based on the following ideal coupled irreducible asymptotic dichotomy: "Information Reliable Predictability" and "Information Reliable Unpredictability" subsystems. To behave realistically, overall system must guarantee both Logical Closure and Logical Aperture, both fed by environmental "noise" (better… from what human beings call "noise"). So, a natural operating point can emerge as a new Trans-disciplinary Reality Level, out of the Interaction of Two Complementary Irreducible Information Management Subsystems within their environment. In this way, it is possible to extend the traditional EPM approach in order to profit by both classic EPM intrinsic Self-Reflexive Functional Logical Closure and new numeric CICT Self-Reflective Functional Logical Aperture. -

Initial Steps in Development of Computer Science in Macedonia

Initial Steps in Development of Computer Science in Macedonia and Pioneering Contribution to Human-Robot Interface using Signals Generated by a Human Head Stevo Bozinovski 2 Abstract – This plenary keynote paper gives overview of the were engaged in support of nuclear energy research. People pioneering steps in the development of computer science in from Macedonia interested in advanced research and study Macedonia between 1959 and 1988, period of the first 30 years. were part of this effort. Most significant work was done by As part of it, the paper describes the worldwide pioneering Aleksandar Hrisoho, who working together with Branko results achieved in Macedonia. Emphasize is on Human-Robot Soucek in Zagreb, wrote a paper about magnetic core Interface using signals generated by a human head. memories in 1959 [1]. He received formal recognition for this Keywords – pioneering results, Computer Science in work, the award “Nikola Tesla” [2]. He also worked on Macedonia analog-to-digital conversion on which he wrote a paper [3], received a PhD [4], and was cited [5]. So it can be said that authors from Macedonia in early 1960’s already achieved PhD and citation for work related to computer sciences. Their I. INTRODUCTION work was in languages other than Macedonian because they worked outside Macedonia. This paper represents a research work on the history of development of Computer Science in Macedonia from 1959 till 1988, the first thirty years period. The history can be B. 1961-1967: People from Macedonia visiting programming presented in many ways and in this paper the measure of courses outside Macedonia historical events are pioneering steps. -

Biomedical Engineering Graduate Program

Faculty of Medicine and Medical Center (FM/AUBMC) 505 Biomedical Engineering Graduate Program Coordinator: Dawy, Zaher (Electrical & Computer Engineering, SFEA) Co-coordinator: Jaffa, Ayad (Biochemistry & Molecular Genetics, FM) Coordinating Committee Daou, Arij (Biomedical Engineering, SFEA) Members: Darwiche, Nadine (Biochemistry & Molecular Genetics, FM) Kadara, Humam (Biochemistry & Molecular Genetics, FM) Khoueiry, Pierre (Biochemistry & Molecular Genetics,FM) Mhanna, Rami (Biomedical Engineering, SFEA) Oweis, Ghanem (Mechanical Engineering, SFEA) Background The Biomedical Engineering Graduate Program (BMEP) is a joint SFEA and FM interdisciplinary program that offers two degrees that are: Master of Science (MS) in Biomedical Engineering and Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Biomedical Engineering. The BMEP is housed in the SFEA and administered by both SFEA and FM via a joint program coordinating committee (JPCC). The mission of the BMEP is to provide excellent education and promote innovative research enabling students to apply knowledge and approaches from the biomedical and clinical sciences in conjunction with design and quantitative principles, methods, and tools from the engineering disciplines, to address human health related challenges of high relevance to Lebanon, the Middle East, and beyond. The program prepares its students to be leaders in their chosen areas of specialization committed to lifelong learning, critical thinking, and intellectual honesty. The curricula of the MS and PhD degrees are composed of core and elective -

Anticipatory Governance Practical Upgrades

Anticipatory Governance Practical Upgrades Equipping the Executive Branch to Cope with Increasing Speed and Complexity of Major Challenges Leon S. Fuerth with Evan M.H. Faber October 2012 Cover by Meaghan Charlton Graphics and Design by Meaghan Charlton, Evan Faber, and Jocelyn Jezierny Disclaimer The concepts presented in this report were developed by Leon Fuerth during the period 2001–2011 and refined during a series of workshops held at the National Defense University from April 2011–July 2011. The workshops convened experts from in and outside government to vet, validate, and build upon Anticipatory Governance concepts based on strict criteria for practical implementation. All workshops operated under the Chatham House Rule, meaning participants entered under agreement from all parties that the discussion would be private, comments would not be attributed to individual persons, and it would be assumed that participants spoke for themselves personally rather than for any institution. The initiatives proposed in this document represent a synthesis of the best ideas that emerged from the 2011 working group process. The concepts have also undergone supplementary scrutiny in a series of individual encounters with very senior officials from the present and past administrations that took place from September 2011–April 2012. The concepts described herein do not represent the views or opinions of The George Washington University, National Defense University, Department of Defense, Federal Government, or any other institutions associated with the Project on Forward Engagement. Endorsers The following endorsements reflect a consensus within a group of exceptional public servants that—politics aside—our government systems and processes need to be upgraded to reflect the new realities of today’s complex challenges. -

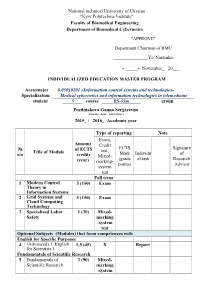

National Technical University of Ukraine "Kyiv Polytechnic Institute" Faculty of Biomedical Engineering Department of Biomedical Cybernetics "APPROVE"

National technical University of Ukraine "Kyiv Polytechnic Institute" Faculty of Biomedical Engineering Department of Biomedical Cybernetics "APPROVE" Department Chairman of BMC _______________Ye. Nastenko « _____» November_ 20___ INDIVIDUALIZED EDUCATION MASTER PROGRAM Area/major 8.05010101 «Information control systems and technologies» Specialization Medical cybernetics and information technologies in telemedicine student 5 course BS-51m group Pozdniakova Ganna Sergeyevna (surname, name, patronymic) 2015_ / 2016_ Academic year Type of reporting Note Exam, Amount Credit ECTS Signature № of ECTS test, Title of Module Mark Individu of s/n credits Mixed- (grade al task Research (year) marking- points) Advisor system test Fall term 1 Modern Control 5 (150) Exam Theory in Information Systems 2 Grid Systems and 5 (150) Exam Cloud Computing Technology 3 Specialized Labor 1 (30) Mixed- Safety marking -system test Optional Subjects (Modules) that form competences with English for Specific Purposes 4 (Advanced).1. English 1,5 (45) Х Report for Scientists 1. Fundamentals of Scientific Research 5 Fundamentals of 3 (90) Mixed- Scientific Research marking -system Type of reporting Note Exam, Amount Credit ECTS Signature № of ECTS test, Title of Module Mark Individu of s/n credits Mixed- (grade al task Research (year) marking- points) Advisor system test test Professional and Practical training Biomedical Cybernetics 6 Fundamentals of 6,5 (195) Exam Settle Synergetics. Models of ment Nonlinear Dynamics. and graphi c work Medical informational systems -

The Future Can't Wait

“Government agencies are not normally known for thinking outside the box. This book is the rare and The Future Can’t Can’t Future The This book is the rare and welcome exception, a genuine breath of fresh welcome exception, a genuine air. It is the kind of project that should become the norm in Washington, breath of fresh air. challenging all of us to look beyond what one participant describes as the – Anne-Marie Slaughter tyrannies of the in-box, the demand for immediate results, the focus on a Former Director of Policy Planning, single sector, and reliance on uni-dimensional measures of success. It should United States Department of State become an annual exercise.” Anne-Marie Slaughter W Bert G. Kerstetter ‘66 University Professor of Politics and International Affairs ait Princeton University Former Director of Policy Planning, United States Department of State Over-the-Horizon Views on Development “Perhaps the most embarrassing failure of international development agencies has been their excessive focus on programming for past problems instead of anticipating the challenges of the future. Black swans have derailed many a development budget by forcing the reallocation of scarce resources to address game-changing events no one anticipated. This thoughtful and timely book remedies this failure and provides some useful guidance to policymaking on how to catch the next black swan before it catches us.” Andrew S. Natsios Executive Professor George H. W. Bush School of Government and Public Service Former USAID Administrator “Development assistance is one of our most powerful and cost-effective tools of national power to promote global democracy and economic growth. -

Stronger Physical and Biological Measurement Strategy for Biomedical and Wellbeing Application by CICT

Recent Advances in Biology, Biomedicine and Bioengineering Stronger Physical and Biological Measurement Strategy for Biomedical and Wellbeing Application by CICT RODOLFO A. FIORINI Department of Electronics, Information and Bioengineering (DEIB) Politecnico di Milano 32, Piazza Leonardo da Vinci, 20133 Milano ITALY [email protected] http://www.linkedin.com/pub/rodolfo-a-fiorini-ph-d/45/277/498 Abstract: - Traditional good data and an extensive factual knowledge base still do not guarantee a biomedical or clinical good decision; good problem understanding and problem-solving skills are equally important. Decision theory, based on a "fixed universe" or a model of possible outcomes, ignores and minimizes the effect of events that are "outside model". In fact, deep epistemic limitations reside in some parts of the areas covered in decision making. Mankind’s best conceivable worldview is at most a partial picture of the real world, a picture, a representation centered on man. Clearly, the observer, having incomplete information about the real underlying generating process, and no reliable theory about what the data correspond to, will always make mistakes, but these mistakes have a certain pattern. Unfortunately, the "probabilistic veil" can be very opaque computationally, and misplaced precision leads to confusion. Paradoxically if you don’t know the generating process for the folded information, you can’t tell the difference between an information-rich message and a random jumble of letters. This is "the information double-bind" (IDB) problem in contemporary classic information and algorithmic theory. The first attempt to identify basic principles to get stronger physical and biological measurement and correlates from experiment has been developing at Politecnico di Milano since the end of last century. -

ENGLISH PROFICIENCY in CYBERNETICS

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF UKRAINE TARAS SHEVCHENKO NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF KYIV Maryna Rebenko ENGLISH PROFICIENCY in CYBERNETICS B2 – C1 Textbook for Students of Computer Science and Cybernetics UDC R Reviewers: Candidate of Economic Sciences, Docent P. V. Dz iuba, Doctor of Economic Sciences, Full Professor R. O. Kostyrk o, Doctor of Economic Sciences, Full Professor V. G. Shvets , Candidate of Pedagogic Sciences, Docent L. M. Ruban Recommended by the Academic Council Faculty of Economics (Protocol No 2 dated 25 October 20160 Adopted by the Scientific and Methodological Council Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv (Protocol No 3 dated 25 November 2016) Rebenko Maryna R English proficiency in Cybernetic: Textbook / M. Rebenko. – K. : Publishing and Polygraphic Centre "The University of Kyiv", 2017. – 160 р. ISBN 978-966-439-881-4 The English Proficiency in Cybernetics textbook has been designed for the students completing their 4th year of undergraduate study in Applied Mathematics, Computer Sciences, System Analysis, and Software Engineering. The course ap- plies for those students who have a specific area of academic or professional in- terest. Technology-integrated English for Specific Purposes content of the text- book gives the students the opportunity to develop their English competence suc- cessfully. It does this by meeting national and international academic standards, professional requirements and students’ personal needs. UDC ISBN 978-966-439-881-4 © Rebenko M., 2017 © Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Publishing and Polygraphic Centre "The University of Kyiv ", 2017 2 Contents Preface ...............................................................................................5 Unit 1. Cybernetics ...........................................................................6 Part I. Birth of the Science ...........................................................6 Part II. Norbert Wiener, the Father of Cybernetics ....................11 Unit 2.