Download Street Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Welcome to Clarks Village ENTRANCE 50 54 ENTRANCE KING ARTHUR’S FOREST H/S H/S ADVENTURE PLAY PARK

Welcome to Clarks Village ENTRANCE 50 54 ENTRANCE KING ARTHUR’S FOREST H/S H/S ADVENTURE PLAY PARK ENTRANCE A/B 92 94 92C 1A 74 1B 73 2A/2B/2C 75 48 49 50-52 72 47 22 76 21 77 46 78 71 20 79 45 59B 18 80 70 82 81 44 16-17 14 69 15 13 68 67 ENTRANCE ENTRANCE 43 59A 66 65 64 42 59 35 28 4B 10 11 12 83 60-61 62 63 41 34A 4A 9 40 34 3 8 MO NORTHSIDE 7 CAR PARK 38 39 A 29 32-33 YOU 37D 23 6 C GRANGE 37 ARE CAR PARK 5 37B 4 HERE A 23 -2 37 1-2 30 31 25 53 26 58 57 27A 54-56 ENTRANCE 27B ENTRANCE SOUTHLEAZE CAR & COACH PARK FASHION FOOTWEAR HANDBAGS AND LUGGAGE SERVICES 47 Barbour 21 Clarks 59 Fiorelli Baby Changing 26 Bench 13 Clarks Factory Shop 65 IT Luggage Cafés/Restaurants 12 Ben Sherman 7 Ecco 83 Osprey London Cash Dispenser 45 Calvin Klein 28 Skechers 16/17 Radley Disabled Facilities 15 Cotton Traders 29 Samsonite Shopmobility 69 Crew Clothing Company SPORTS & OUTDOOR Wheelchair hire available – telephone 25 French Connection HOME AND LIFESTYLE booking line 01458 447384 or 54/56 GAP Outlet 48 Asics see website for details. 14 Henri Lloyd 60-61 Mountain Warehouse 2C Bedeck First Aid 35 Hobbs 27B The North Face 2A Dartington Crystal 50H/S Fusion Recruitment 30 Jaeger 76 Sports Direct 2B Denby Toilets 31 Jeff Banks 38 Tog 24 40 Le Creuset Shoe Museum 62 Joules 5 Trespass 1B Portmeirion 01458 842243 23A Lakeland Leather 64 ProCook Tourist Information Centre 01458 447384 49 Levi’s GIFTS AND ACCESSORIES 46 Tefal Home & Cook 23/24 M&S Outlet 58 Tempur Management Office 70 Musto 59A Chapelle 44 Villeroy & Boch 01458 840064 71 Next Clearance -

A Wander Around Walton and Small Moor

A Listed as Waltone in the Doomsday book, this area was an estate of Glastonbury Abbey since at least the 8th century. Walton is situated on a woody hill, also known as a wold, which is where the name Walton may have derived from; it is also suggested that it could Avalon Marshes Heritage Walks: mean settlement of the Welsh. During 1753 the main road through Walton (now the A39) became a turnpike road; the route is part of the Wells Trust, with the road being known as A wander around Walton the ‘Western Road’ south west of the City of Wells and the ‘Bristol Road’ to the north. The Church of the Holy Trinity in Walton was built in 1866 by John Norton; the first church recorded was Norman, built around 1150. and Small Moor B Whitley wood gave its name to the Whitley Hundred (a county administrative division) which was probably formed in the latter part of the 12th century; it still contains the ruins of the Hundred house which was a meeting place for the Hundred court. C Small Moor was added to the parish of Walton during inclosure; prehistoric flints and fragments of medieval pottery have been found there. D On 22nd April 1707 Henry Fielding was born at Sharpham Park, a novelist and playwright well known for the novel ‘The history of Tom Jones, a foundling’. Fielding was also London’s Chief Magistrate for a time and with the help of his half-brother John, formed the Bow Street Runners. E Abbot’s Sharpham was built by the Abbott Richard Beere of Glastonbury Abbey; it was here the last Abbott of Glastonbury, Richard Whiting, was arrested before his execution on Glastonbury Tor. -

Saints, Monks and Bishops; Cult and Authority in the Diocese of Wells (England) Before the Norman Conquest

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 3 Issue 2 63-95 2011 Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest Michael Costen University of Bristol Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Costen, Michael. "Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 3, 2 (2011): 63-95. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol3/iss2/4 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Costen Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest Michael Costen, University of Bristol, UK Introduction This paper is founded upon a database, assembled by the writer, of some 3300 instances of dedications to saints and of other cult objects in the Diocese of Bath and Wells. The database makes it possible to order references to an object in many ways including in terms of dedication, location, date, and possible authenticity, and it makes data available to derive some history of the object in order to assess the reliability of the information it presents. -

The Early Medieval Period, Its Main Conclusion Is They Were Compiled at Malmesbury

Early Medieval 10 Early Medieval Edited by Chris Webster from contributions by Mick Aston, Bruce Eagles, David Evans, Keith Gardner, Moira and Brian Gittos, Teresa Hall, Bill Horner, Susan Pearce, Sam Turner, Howard Williams and Barbara Yorke 10.1 Introduction raphy, as two entities: one “British” (covering most 10.1.1 Early Medieval Studies of the region in the 5th century, and only Cornwall by the end of the period), and one “Anglo-Saxon” The South West of England, and in particular the three (focusing on the Old Sarum/Salisbury area from the western counties of Cornwall, Devon and Somerset, later 5th century and covering much of the region has a long history of study of the Early Medieval by the 7th and 8th centuries). This is important, not period. This has concentrated on the perceived “gap” only because it has influenced past research questions, between the end of the Roman period and the influ- but also because this ethnic division does describe (if ence of Anglo-Saxon culture; a gap of several hundred not explain) a genuine distinction in the archaeological years in the west of the region. There has been less evidence in the earlier part of the period. Conse- emphasis on the eastern parts of the region, perhaps quently, research questions have to deal less with as they are seen as peripheral to Anglo-Saxon studies a period, than with a highly complex sequence of focused on the east of England. The region identi- different types of Early Medieval archaeology, shifting fied as the kingdom of Dumnonia has received detailed both chronologically and geographically in which issues treatment in most recent work on the subject, for of continuity and change from the Roman period, and example Pearce (1978; 2004), KR Dark (1994) and the evolution of medieval society and landscape, frame Somerset has been covered by Costen (1992) with an internally dynamic period. -

Coach-Trips-2019.Pdf

Coach Trips Age UK Exeter Coach Trips Thursday 14/03 - Cheltenham £14.50 Cheltenham, in Gloucestershire, is home to the renowned Cheltenham Festival and the Gold Cup. It’s also known for Regency buildings, including the Pittville Pump Room, a remnant of Cheltenham’s past as a spa town. There’s fine art at The Wilson museum, and the Victorian Everyman Theatre has an ornate auditorium. Tuesday 02/04 - Salcombe £13.00 Salcombe is a popular resort town in the South Hams. Close to the mouth of the Kingsbridge Estuary, mostly built on the steep west side of the estuary. It lies within the South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Wednesday 15/05 - Cardiff £14.50 A port city on the south coast of Wales, where the River Taff meets the Severn Estuary, Cardiff was proclaimed the nation’s capital in 1955. The revitalized waterfront at Cardiff Bay includes the Wales Millennium Centre, and lots of cafes, restaurants and shops at Mermaid Quay. Monday 10/06 - Weymouth £13.00 A seaside town in Dorset, Weymouth’s sandy beach is dotted with colorful beach huts and backed by Georgian houses. Jurassic Skyline, a revolving viewing tower, and Victorian Nothe Fort offer harbour views. Weymouth Sealife Park is home to sharks, turtles and stingrays. On the fossil-rich Jurassic Coast is pebbly Chesil Beach. A causeway leads to Portland Island with its lighthouse and birdlife. Friday 12/07 - Bude £13.00 There’s a lot to love about Bude. With a laidback allure all of its own, and so much to see and do, it has something for everyone. -

Gosh Locations

GOSH LOCATIONS - APRIL POSTAL COUNCIL ALTERNATIVE SECTOR NAME MONTH (DATES) SECTOR BA1 1 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council St James's Parade, Bath 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 2 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Royal Crescent, Bath 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 3 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Lower Weston) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 4 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Weston) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 5 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Lansdown) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 6 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Larkhall, Walcot) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 7 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Batheaston, Bathford 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 8 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Upper Swainswick, Batheaston 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 9 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Kelston, Lansdown, North Stoke 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 0 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Timsbury, Farmborough 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 1 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Twerton, Southdown, Whiteway) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 2 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Odd Down, Bloomfield, Bath 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 3 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Twerton) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 4 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Bathwick) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 5 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Combe Down) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 6 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Bathampton, Bathwick, Widcombe) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 7 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Limpley Stoke, Norton St. -

Alice Buckton's Glastonbury Pilgrimage

Alice Buckton’s Glastonbury Pilgrimage Last year I gave a paper at the ABS conference in Oxford (Saturday 22nd June 2019) on the subject of the pilgrimage around Glastonbury used by Alice Buckton, which formed part of her spiritual pracKce that she shared with likeminded friends and guests at her establishment at the foot of Glastonbury Tor. This is an updated version of the paper which includes a considerable amount of new material. - Lil Osborn, 2020 From the Silence of Time, Time’s Silence borrow In the heart of To-day is the word of Tomorrow The Builders of Joy are the Children of Sorrow Fiona Mcleaod Alice Buckton (1867 – 1944) I have wriRen extensively about Alice Mary Buckton (Osborn, 2014) (Osborn, Alice Buckton - Baha'i Mysc, 2014), this paper focuses specifically on one specific aspect of her spiritual pracKce, that of a pilgrimage around Glastonbury and examining this acKvity in an aempt to unravel her beliefs in parKcular in relaKon to the Baha’i Faith. Buckton came to live in Glastonbury in 1913, she had first visited the town in 1907 at the behest of Wellesley Tudor Pole (1884 – 1968), earlier that year she had been present at a meeng in Dean’s Yard hosted by Basil Wilberforce (1841 – 1914) where Pole first made public the details of his finding of a bowl in a well in Glastonbury and the immense spiritual significance he aRributed to it (Bentham, 1993). In 1913 the large building recently vacated by the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart in Glastonbury came up for sale, and Alice Buckton managed “by selling all she owned”, to purchase it. -

A Toponomastic Contribution to the Linguistic Prehistory of the British Isles

A toponomastic contribution to the linguistic prehistory of the British Isles Richard Coates University of the West of England, Bristol Abstract It is well known that some of the major island-names of the archipelago consisting politically of the Republic of Ireland, the United Kingdom, and the UK Crown Dependencies are etymologically obscure. In this paper, I present and cautiously analyse a small set of those which remain unexplained or uncertainly explained. It is timely to do this, since in the disciplines of archaeology and genetics there is an emerging consensus that after the last Ice Age the islands were repopulated mainly by people from a refuge on the Iberian peninsula. This opinion is at least superficially compatible with Theo Vennemann’s Semitidic and Vasconic hypotheses (e.g. Vennemann 1995), i.e. that languages (a) of the Afroasiatic family, and (b) ancestral to Basque, are important contributors to the lexical and onomastic stock of certain European languages. The unexplained or ill-explained island names form a small set, but large enough to make it worthwhile to attempt an analysis of their collective linguistic heritage, and therefore to give – or fail to give – preliminary support to a particular hypothesis about their origin.* * This paper is a development of one read at the 23rd International Congress of Onomastic Sciences, Toronto, 17-22 August 2008, and I am grateful to the editors of the Proceedings (2009), Wolfgang Ahrens, Sheila Embleton, and André Lapierre, for permission to re-use some material. A version was also read at the Second Conference on the Early Medieval Toponymy of Ireland and Scotland, Queen’s University Belfast, 13 November 2009. -

Glastonbury Companion

John Cowper Powys’s A Glastonbury Romance: A Reader’s Companion Updated and Expanded Edition W. J. Keith December 2010 . “Reader’s Companions” by Prof. W.J. Keith to other Powys works are available at: http://www.powys-lannion.net/Powys/Keith/Companions.htm Preface The aim of this list is to provide background information that will enrich a reading of Powys’s novel/ romance. It glosses biblical, literary and other allusions, identifies quotations, explains geographical and historical references, and offers any commentary that may throw light on the more complex aspects of the text. Biblical citations are from the Authorized (King James) Version. (When any quotation is involved, the passage is listed under the first word even if it is “a” or “the”.) References are to the first edition of A Glastonbury Romance, but I follow G. Wilson Knight’s admirable example in including the equivalent page-numbers of the 1955 Macdonald edition (which are also those of the 1975 Picador edition), here in square brackets. Cuts were made in the latter edition, mainly in the “Wookey Hole” chapter as a result of the libel action of 1934. References to JCP’s works published in his lifetime are not listed in “Works Cited” but are also to first editions (see the Powys Society’s Checklist) or to reprints reproducing the original pagination, with the following exceptions: Wolf Solent (London: Macdonald, 1961), Weymouth Sands (London: Macdonald, 1963), Maiden Castle (ed. Ian Hughes. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1990), Psychoanalysis and Morality (London: Village Press, 1975), The Owl, the Duck and – Miss Rowe! Miss Rowe! (London: Village Press, 1975), and A Philosophy of Solitude, in which the first English edition is used. -

157 High Street, Street, Somerset, BA16 0ND

www.torestates.co.uk Telephone: 01458 888020 20 High Street 73 High Street [email protected] Glastonbury Street [email protected] BA6 9DU BA16 0EG [email protected] 157 High Street, Street, Somerset, BA16 0ND £105,000 – Freehold A beautifully presented, refurbished maisonette style property, conveniently situated within easy walking distance to all the High Street amenities. Refurbished throughout, the property is being offered with NO ONWARD CHAIN. An early viewing is essential. The property comprises entrance hall, open plan lounge/diner/kitchen, cloakroom, one double bedroom with en-suite shower room. www.torestates.co.uk Telephone: 01458 888020 157 High Street, Street, Somerset, BA16 0ND AMENITIES & RECREATION Kitchen Area: Street is a thriving mid Somerset town famous as A range of fitted wall, drawer and base units with the home of Millfield School, Clarks Shoes and laminate work surface over. Inset stainless steel more recently Clarks Village Shopping Centre sink with drainer. Tiling to splash prone areas. complementing the High Street shopping facilities. Space for cooker with stainless steel cooker hood Street also provides Crispin Secondary School, over. Space and plumbing for washing machine. Strode College, a theatre, open-air and indoor pools and a choice of pubs and restaurants. The historic town of Glastonbury is approximately 3 miles away and boasts a variety of unique local shops. The Cathedral City of Wells is 8 miles whilst the nearest M5 motorway interchange at Dunball (Junction 23) is 12 miles. Bristol, Bath, Taunton and Yeovil are all within commuting distance. Entrance Hall UPVC double glazed front door. -

Street 6 Crispin Centre, Street, Somerset, BA16 0HP

RETAIL UNITS - 3,000-25,000 SQ FT AVAILABLE Street 6 Crispin Centre, Street, Somerset, BA16 0HP LARGE FLOORPLATE Location Street has a shopper population of 85,868 (CACI 2014) and a catchment population of 164,005 (Experian 2015). The town is situated in Somerset, approximately 24 miles south of Bristol, 7 miles south-west of Wells and 2 miles south-west of Glastonbury. The subject property is located within the Crispin Centre, adjacent to the Southside car park providing 198 spaces, of which 82 spaces are demised to Unit 6 and available to shoppers free of charge, whilst the remainder are available on a pay and display basis. Immediately opposite the Crispin Centre is the UK’s first ever outlet centre, Clarks Village with 90 designer and high street stores, 9 catering units and 1,400 parking spaces. In terms of outlet centres, Clarks Village is ranked 7th in the UK by comparison expenditure (CACI 2014) ahead of Swindon, Bridgend and Gloucester Quays. Accommodation The subject property provides the following approximate gross internal areas: Sq m Sq ft For more information, please contact: Ground Floor 1,925.4 20,725 Spencer Wilson +44 (0)117 910 5271 First Floor 373.0 4,015 +44 (0)7736 010 220 [email protected] The ground floor is capable of sub-division providing stores from 3,000 to Rivergate House 16,000 sq ft. Floor plans are available upon request. 70 Redcliff Street Bristol Terms BS1 6AL Units are available on new effectively full repairing and insuring leases for a term of 10 years, subject to five yearly upward only rent reviews. -

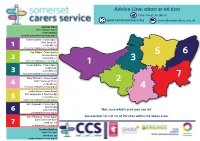

A3 Map and Contacts

Amanda Stone Carers Support Agent 07494 883 654 [email protected] Elaine Gardner - Carers Agent West Somerset 07494 883 134 C D 1 [email protected] Kay Wilton - Carers Agent A Taunton Deane ? 07494 883 541 2 [email protected] Lauren Giddins - Carers Agent Sedgemoor E 07494 883 579 3 [email protected] @ Mary Withams - Carers Agent B South Somerset (West) 4 07494 883 531 [email protected] Jackie Hayes - Carers Agent East Sedgemoor & West Mendip 07494 883 570 5 [email protected] John Lapwood - Carers Agent East Mendip 07852 961 839 Not sure which area you are in? 6 [email protected] Cath Holloway - Carers Agent See overleaf for full list of Parishes within the above areas South Somerset (East) 07968 521 746 7 [email protected] Caroline Harding Agent Manager 07908 160 733 [email protected] 1 2 • Ash Priors • Corfe • Norton Fitzwarren • Thornfalcon • Bicknoller • Exton • Oare • Washford • Ashbrittle • Cotford St Luke • Nynehead • Tolland • Brompton Ralph • Exford • Old Cleeve • Watchet • Bathealton • Cothelstone • Oake • Trull • Brompton Regis • Exmoor • Porlock • West Quantoxhead • Bishops Hull • Creech St Michael • Orchard Portman • West Bagborough • Brushford • Holford • Sampford Brett • Wheddon • Bishops Lydeard • Curland • Otterford • West Buckland • Carhampton • • Selworthy • Winsford • Bickenhall • Durston • Pitminster • West Hatch • Clatworthy • Kilve • Skilgate • Williton • Bradford-on-Tone • Fitzhead • Ruishton • Wellington