Hong Kong and Bollywood in the Global Soft Power Contest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writers and Creative Advisors Selected for Drishyam | Sundance Institute Screenwriters Lab in Udaipur, India April 48

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media contacts: March 23, 2016 Chalena Cadenas 310.360.1981 [email protected] Mauli Singh [email protected] Writers and Creative Advisors Selected for Drishyam | Sundance Institute Screenwriters Lab in Udaipur, India April 48 Lab Recognizes and Supports Six Emerging Independent Filmmakers from India Los Angeles, CA — Sundance Institute and Drishyam Films today announced the artists and creative advisors selected for the second Drishyam | Sundance Institute Screenwriters Lab in Udaipur, India April 48. The Lab supports emerging filmmakers in India, as part of the Institute’s sustained commitment to international artists, which in the last 25 years has included programs in Brazil, Mexico, Jordan, Turkey, Japan, Cuba, Israel and Central Europe. Now in its second year, the fourday Lab is a creative and strategic partnership between Drishyam Films and Sundance Institute, and gives independent screenwriters the opportunity to work intensively on their feature film scripts in an environment that encourages innovation and creative risktaking. The Lab is centered around oneonone story sessions with creative advisors. Screenwriting fellows engage in an artistically rigorous process that offers lessons in craft, a fresh perspective on their work and a platform to fully realize their material. Leading the Lab in India is Drishyam founder, Manish Mundra. He said, “A beautiful heritage city in my hometown of Rajasthan, Udaipur forms an ideal writers retreat, and is the perfect environment for a diverse group of emerging writers and renowned mentors to have a refreshing and productive exchange. Our goal is that the six selected Indian projects, after undergoing a comprehensive mentoring process, will quickly move from script to screen and make their mark globally. -

Media Release Reliance Entertainment and Phantom Films

Media Release Reliance Entertainment and Phantom Films’ Super 30 to release on 23rd Nov, 2018 Directed by Vikas Bahl, “Super 30” will star Hrithik Roshan Mumbai, November 4, 2017: Anil D. Ambani led Reliance Entertainment and Phantom Films’ “Super 30” directed by Vikas Bahl and starring Hrithik Roshan in the lead role will release on 23rd November 2018. Super 30 is a story of a mathematics genius from a modest family in Bihar, Anand Kumar, who was told that only a king’s son can become a king. But he went on to prove how one poor man could create some of the world’s most genius minds. Anand Kumar’s training program is so effective that students post cracking IIT have gone on to become some of the most successful professionals. Many students trained under the Super 30 program have joined some of the top global companies like Adobe, Samsung Research Institute, Amazon etc. Anand Kumar said, “I trust Vikas Bahl with my life story and I believe that he will make a heartfelt film. I am a rooted guy so I feel some level of emotional quotient is required to live my life on screen. I have seen that in Hrithik – on and off screen. I have full faith in his capabilities.” Vikas Bahl, truly inspired by Anand Kumar’s initiative, said, “Super 30 is a story of the struggles of those genius kids who have one opportunity and how those 30 amongst thousands of others redefine success. The film will focus on the Super 30 program that Kumar started, which trains 30 IIT aspirants to crack its entrance test.” Vikas Bahl is one of the most critically and commercially acclaimed directors of our country. -

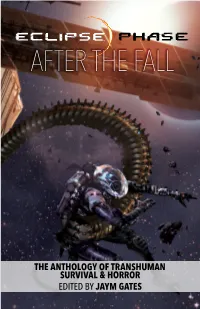

Eclipse Phase: After the Fall

AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 Advance THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN Reading SURVIVAL & HORROR Copy Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. Some content licensed under a Creative Commons License (BY-NC-SA); Some Rights Reserved. © 2016 AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN SURVIVAL & HORROR Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. -

Bullet in the Head

JOHN WOO’S Bullet in the Head Tony Williams Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Tony Williams 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-968-5 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head 1 2 Bullet in the Head 23 3 Aftermath 99 Appendix 109 Notes 113 Credits 127 Filmography 129 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head Like many Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 90s, John Woo’s Bullet in the Head contains grim forebodings then held by the former colony concerning its return to Mainland China in 1997. Despite the break from Maoism following the fall of the Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s movement towards capitalist modernization, the brutal events of Tiananmen Square caused great concern for a territory facing many changes in the near future. Even before these disturbing events Hong Kong’s imminent return to a motherland with a different dialect and social customs evoked insecurity on the part of a population still remembering the violent events of the Cultural Revolution as well as the Maoist- inspired riots that affected the colony in 1967. -

Laurent Courtiaud & Julien Carbon

a film by laurent courtiaud & julien carbon 1 Red_nights_93X66.indd 1 7/05/10 10:36:21 A FILM BY LAURENT COURTIAUD & JULIEN CARBON HonG KonG, CHIna, FranCe, 2009 FrenCH, CantoneSe, MandarIn 98 MInuteS World SaleS 34, rue du Louvre | 75001 PARIS | Tel : +33 1 53 10 33 99 [email protected] | www.filmsdistribution.com InternatIonal PreSS Jessica Edwards Film First Co. | Tel : +1 91 76 20 85 29 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS A CantoneSE OPERA TELLS THE TRAGEDY of THE Jade EXecutioner, WHO HAD created A PoiSon THat KILLED by GIVING THE ultimate PLEASURE. THIS LEGEND HAPPENS AGAIN noWadayS WHEN A FrencH Woman EScaPES to HonG KonG AFTER HAVING KILLED HER loVER to taKE AN ANTIQUE HoldinG, THE infamouS Potion. SHE becomeS THE HAND of fate THat PITS A TAIWANESE GANGSTER AGAINST AN EPicurean Woman murderer WHO SEES HERSELF AS A NEW incarnation of THE Jade EXecutioner. 4 3 DIRECTORS’ NOTE OF INTENT “ Les Nuits Rouges du Bourreau de But one just needs to wander at night along Jade ”. “Red Nights Of The Jade Exe- the mid-levels lanes on Hong Kong island, a cutioner”. The French title reminds maze of stairs and narrow streets connecting of double bills cinemas that scree- ancient theatres, temples and high tech buil- ned Italian “Gialli” and Chinese “Wu dings with silent mansions hidden among the trees up along the peak, to know this is a per- Xia Pian”. The end of the 60s, when fect playground for a maniac killer in trench genre and exploitation cinema gave coat hunting attractive but terrified victims “à us transgressive and deviant pictures, la Mario Bava”. -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

Donnie Yen's Kung Fu Persona in Hypermedia

Studies in Media and Communication Vol. 4, No. 2; December 2016 ISSN 2325-8071 E-ISSN 2325-808X Published by Redfame Publishing URL: http://smc.redfame.com Remediating the Star Body: Donnie Yen’s Kung Fu Persona in Hypermedia Dorothy Wai-sim Lau1 113/F, Hong Kong Baptist University Shek Mun Campus, 8 On Muk Street, Shek Mun, Shatin, Hong Kong Correspondence: Dorothy Wai-sim Lau, 13/F, Hong Kong Baptist University Shek Mun Campus, 8 On Muk Street, Shek Mun, Shatin, Hong Kong. Received: September 18, 2016 Accepted: October 7, 2016 Online Published: October 24, 2016 doi:10.11114/smc.v4i2.1943 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.11114/smc.v4i2.1943 Abstract Latest decades have witnessed the proliferation of digital media in Hong Kong action-based genre films, elevating the graphical display of screen action to new levels. While digital effects are tools to assist the action performance of non-kung fu actors, Dragon Tiger Gate (2006), a comic-turned movie, becomes a case-in-point that it applies digitality to Yen, a celebrated kung fu star who is famed by his genuine martial dexterity. In the framework of remediation, this essay will explore how the digital media intervene of the star construction of Donnie Yen. As Dragon Tiger Gate reveals, technological effects work to refashion and repurpose Yen’s persona by combining digital effects and the kung fu body. While the narrative of pain and injury reveals the attempt of visual immediacy, the hybridized bodily representation evokes awareness more to the act of representing kung fu than to the kung fu itself. -

Masaan-Press-Kit.Pdf

MACASSAR PRODUCTIONS, PATHÉ ET AND DRISHYAM FILMS PRÉSENTENT PRESENT Durée Length : 1H43 Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.pathefilms.com Material can be downloaded on www.patheinternational.com DISTRIBUTION FRENCH DISTRIBUTION & INTERNATIONAL SALES PATHÉ DISTRIBUTION 2, rue Lamennais – 75008 Paris Tél. : 01 71 72 30 00 www.pathefilms.com www.patheinternational.com À CANNES IN CANNES INTERNATIONAL SALES Boutique Bodyguard Résidences du Grand Hôtel - IBIS Entrance 45, la Croisette Apartement 4 A/E - 4th floor Jardins du Grand Hôtel Tél. : +33 4 93 68 24 31 06400 Cannes [email protected] Tél. : 04 93 99 91 34 RELATIONS PRESSE INTERNATIONAL PRESS LE PUBLIC SYSTÈME CINÉMA Céline PETIT, Clément REBILLAT, Celia MAHISTRE & Anne-Sophie TRINTIGNAC 40, rue Anatole France – 92594 Levallois-Perret Cedex Tél. : 01 41 34 23 50 [email protected] À CANNES IN CANNES RELATIONS PRESSE FRANCE & INTERNATIONAL LE PUBLIC SYSTÈME CINÉMA Céline PETIT, Clément RÉBILLAT, Celia MAHISTRE & Anne-Sophie TRINTIGNAC 29, rue Bivouac Napoléon – 06400 Cannes Tél. : +33 7 86 23 90 85 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Bénarès, la cité sainte au bord du Gange, punit cruellement ceux qui jouent Benares, the holy city on the banks of the Ganges, reserves a cruel punishment avec les traditions morales. Deepak, un jeune homme issu des quartiers for those who play with moral traditions. Deepak, a young man from a poor pauvres, tombe éperdument amoureux d’une jeune fille qui n’est pas de la neighborhood, falls hopelessly in love with a young girl from a different caste. même caste que lui. -

East Bay Deputy Held in Drug Case Arrest Linked to Ongoing State Narcotics Agent Probe

Sunday, March 6, 2011 California’s Best Large Newspaper as named by the California Newspaper Publishers Association | $3.00 Gxxxxx• TOP OF THE NEWS Insight Bay Area Magazine WikiLeaks — 1 Newsom: Concerns Spring adventure World rise over S.F. office deal 1 Libya uprising: Reb- How Europe with donor. C1 tours from the els capture a key oil port caves in to U.S. 1 Shipping: Nancy Pelo- Galapagos to while state forces un- si extols the importance leash mortar fire. A5 pressure. F6 of local ports. C1 South Africa. 6 Sporting Green Food & Wine Business Travel 1 Scouting triumph: 1 Larry Goldfarb: Marin The Giants picked All about falafel County hedge fund manager Special Hawaii rapidly rising prospect who settled fraud charges Brandon Belt, right, — with three stretched the truth about section touts 147th in the ’09 draft. B1 recipes. H1 charitable donations. D1 Kailua-Kona. M1 RECOVERY East Bay deputy held in drug case Arrest linked to ongoing state narcotics agent probe By Justin Berton custody by agents representing CHRONICLE STAFF WRITER the state Department of Justice and the district attorney’s of- A Contra Costa County sher- fice. iff’s deputy has been arrested in Authorities did not elaborate connection with the investiga- on the details of the alleged tion of a state narcotics agent offenses, but a statement from who allegedly stole drugs from the Contra Costa County Sher- Michael Macor / The Chronicle evidence lockers, authorities iff’s Department said Tanabe’s Chris Rodriguez (4) of the Bay Cruisers shoots over Spencer Halsop (24) of the Utah Jazz said Saturday. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The wuxia film is the oldest genre in the Chinese cinema that has remained popular to the present day. Yet despite its longevity, its history has barely been told until fairly recently, as if there was some force denying that it ever existed. Indeed, the genre was as good as non-existent in China, its country of birth, for some fifty years, being proscribed over that time, while in Hong Kong, where it flowered, it was gen- erally derided by critics and largely neglected by film historians. In recent years, it has garnered a following not only among fans but serious scholars. David Bordwell, Zhang Zhen, David Desser and Leon Hunt have treated the wuxia film with the crit- ical respect that it deserves, addressing it in the contexts of larger studies of Hong Kong cinema (Bordwell), the Chinese cinema (Zhang), or the generic martial arts action film and the genre known as kung fu (Desser and Hunt).1 In China, Chen Mo and Jia Leilei have published specific histories, their books sharing the same title, ‘A History of the Chinese Wuxia Film’ , both issued in 2005.2 This book also offers a specific history of the wuxia film, the first in the English language to do so. It covers the evolution and expansion of the genre from its beginnings in the early Chinese cinema based in Shanghai to its transposition to the film industries in Hong Kong and Taiwan and its eventual shift back to the Mainland in its present phase of development. Subject and Terminology Before beginning this history, it is necessary first to settle the question ofterminology , in the process of which, the characteristics of the genre will also be outlined. -

1 Chinese Cinema Survey: 1980–Present Film S142 / Eall

CHINESE CINEMA SURVEY: 1980–PRESENT FILM S142 / EALL S258 Meeting Times: T,Th 1-2:50pm; Session B (July 12-August 13) Instructor: Xueli Wang Email: [email protected] Office Hours: by appointment Course Description: The past four decades have been extraordinarily fruitful for Chinese-language filmmaking. This course will survey key figures, movements, and trends in Sinophone cinema since 1980. Sessions will be structured around eleven films, each an entry point into a broader topic, such as the Fifth and Sixth Generation directors; the Hong Kong New Wave; New Taiwan Cinema; martial arts film; commercial blockbuster; and independent documentary. We will examine these films formally, through shot-by-shot analysis, as well as in relation to major social, political, and economic developments in recent Chinese history, such as the Cultural Revolution; Deng Xiaoping's economic reforms; the Hong Kong handover; the construction of the Three Gorges Dam; and the demolition and displacement of local communities. We will also consider pertinent questions of propaganda and censorship; aesthetics and politics; history and memory; transnational networks and audiences; and what constitutes "Chineseness" in a globalized world. Online Access: ● Seminars and in-class presentations will take place over Zoom. Our Zoom sessions will simulate a live classroom experience with everyone’s audio and video enabled. ● All assigned films will be available to watch remotely, either on Canvas or a streaming site. During some Zoom sessions, we will watch clips together alternating with discussion. ● All required readings and PowerPoint slides and film clips will be available on Canvas. ● Office hours will take place over Zoom, after class and by appointment. -

Redirected from Films Considered the Greatest Ever) Page Semi-Protected This List Needs Additional Citations for Verification

List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Films considered the greatest ever) Page semi-protected This list needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be chall enged and removed. (November 2008) While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications an d organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources focus on American films or we re polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the greatest withi n their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely consi dered among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list o r not. For example, many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best mov ie ever made, and it appears as #1 on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawsh ank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientif ic measure of the film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stack ing or skewed demographics. Internet-based surveys have a self-selected audience of unknown participants. The methodology of some surveys may be questionable. S ometimes (as in the case of the American Film Institute) voters were asked to se lect films from a limited list of entries.