Bendethera Deua National Park Conservation Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gauging Station Index

Site Details Flow/Volume Height/Elevation NSW River Basins: Gauging Station Details Other No. of Area Data Data Site ID Sitename Cat Commence Ceased Status Owner Lat Long Datum Start Date End Date Start Date End Date Data Gaugings (km2) (Years) (Years) 1102001 Homestead Creek at Fowlers Gap C 7/08/1972 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 19.9 -31.0848 141.6974 GDA94 07/08/1972 16/12/1995 23.4 01/01/1972 01/01/1996 24 Rn 1102002 Frieslich Creek at Frieslich Dam C 21/10/1976 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 8 -31.0660 141.6690 GDA94 19/03/1977 31/05/2003 26.2 01/01/1977 01/01/2004 27 Rn 1102003 Fowlers Creek at Fowlers Gap C 13/05/1980 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 384 -31.0856 141.7131 GDA94 28/02/1992 07/12/1992 0.8 01/05/1980 01/01/1993 12.7 Basin 201: Tweed River Basin 201001 Oxley River at Eungella A 21/05/1947 Open DWR 213 -28.3537 153.2931 GDA94 03/03/1957 08/11/2010 53.7 30/12/1899 08/11/2010 110.9 Rn 388 201002 Rous River at Boat Harbour No.1 C 27/05/1947 31/07/1957 Closed DWR 124 -28.3151 153.3511 GDA94 01/05/1947 01/04/1957 9.9 48 201003 Tweed River at Braeside C 20/08/1951 31/12/1968 Closed DWR 298 -28.3960 153.3369 GDA94 01/08/1951 01/01/1969 17.4 126 201004 Tweed River at Kunghur C 14/05/1954 2/06/1982 Closed DWR 49 -28.4702 153.2547 GDA94 01/08/1954 01/07/1982 27.9 196 201005 Rous River at Boat Harbour No.3 A 3/04/1957 Open DWR 111 -28.3096 153.3360 GDA94 03/04/1957 08/11/2010 53.6 01/01/1957 01/01/2010 53 261 201006 Oxley River at Tyalgum C 5/05/1969 12/08/1982 Closed DWR 153 -28.3526 153.2245 GDA94 01/06/1969 01/09/1982 13.3 108 201007 Hopping Dick Creek -

NPWS Pocket Guide 3E (South Coast)

SOUTH COAST 60 – South Coast Murramurang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 61 PARK LOCATIONS 142 140 144 WOLLONGONG 147 132 125 133 157 129 NOWRA 146 151 145 136 135 CANBERRA 156 131 148 ACT 128 153 154 134 137 BATEMANS BAY 139 141 COOMA 150 143 159 127 149 130 158 SYDNEY EDEN 113840 126 NORTH 152 Please note: This map should be used as VIC a basic guide and is not guaranteed to be 155 free from error or omission. 62 – South Coast 125 Barren Grounds Nature Reserve 145 Jerrawangala National Park 126 Ben Boyd National Park 146 Jervis Bay National Park 127 Biamanga National Park 147 Macquarie Pass National Park 128 Bimberamala National Park 148 Meroo National Park 129 Bomaderry Creek Regional Park 149 Mimosa Rocks National Park 130 Bournda National Park 150 Montague Island Nature Reserve 131 Budawang National Park 151 Morton National Park 132 Budderoo National Park 152 Mount Imlay National Park 133 Cambewarra Range Nature Reserve 153 Murramarang Aboriginal Area 134 Clyde River National Park 154 Murramarang National Park 135 Conjola National Park 155 Nadgee Nature Reserve 136 Corramy Regional Park 156 Narrawallee Creek Nature Reserve 137 Cullendulla Creek Nature Reserve 157 Seven Mile Beach National Park 138 Davidson Whaling Station Historic Site 158 South East Forests National Park 139 Deua National Park 159 Wadbilliga National Park 140 Dharawal National Park 141 Eurobodalla National Park 142 Garawarra State Conservation Area 143 Gulaga National Park 144 Illawarra Escarpment State Conservation Area Murramarang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 63 BARREN GROUNDS BIAMANGA NATIONAL PARK NATURE RESERVE 13,692ha 2,090ha Mumbulla Mountain, at the upper reaches of the Murrah River, is sacred to the Yuin people. -

Deua National Park

AUSTRALIA THE AUSTRALIAN c A, ER SPELEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY ~ II No.IIO 1986 II Registered by Australia Post Publication Number NBQ 5116 HEHBKR SOCIETIES & ASSOCIATED ORGANISATIONS COUNCIL HEHBKRS ACT: Canberra Speleological Society 18 Arabana St Aranda ACT 2614 Capital Territory Caving Group PO Box 638 Woden ACT 2606 National University Caving Club c/-Sports Union Australian National university ACT 2600 NSW: Baptist Caving Association 90 Parkes St Helensburg NSW 2508 Blue Mountains Speleological Club PO Box37 Glenbrook NSW 2773 Endeavour Caving & Recreational Club PO Box 63 Miranda NSW 2228 Highland Caving Group PO Box 154 Liverpool NSW 2170 Hills Speoleology Club PO Box 198 Baulkharn Hills NSW 2153 Illawarra Speleological Society PO Box 94 Unanderra NSW 2526 Kempsey Speleological Society 27 River St Kempsey NSW 2440 Macquarie University Caving Group c/-Sports Association Macquarie Uni Nth Ryde NSW 211 3 Metropolitan Speleological Society PO Box 2376 Nth Parramatta NSW 2151 Newcastle And Hunter Valley Speleological Society PO Box 15 Broadrneadow NSW 2292 NSW Institute Of Technology Speleological Society c/-The Union PO Box 123 Broadway NSW 2007 Orange Speleological Society PO Box 752 Orange NSW 2800 RAN Caving Association c/- 30 Douglas Ave Nth Epping NSW 2121 Sydney University Speleological Society Box 35 The Union Sydney University NSW 2006 University Of NSW Speleological Society Box 17 The Union UNSW Kensington NSW 2033 QUEENSLAND: Central Queensland Speleological Society PO Box 538 Rockhampton Qld 4700 University Of Queensland Speleological -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

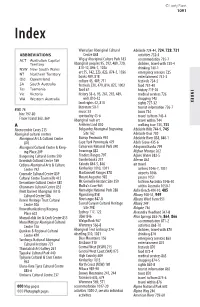

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Braidwood Archaeological Management Plan, Nsw

Archaeological Management Plan BRAIDWOOD ARCHAEOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT PLAN, NSW JUNE 2019 www.nghenvironmental.com.au e [email protected] Sydney Region Canberra - NSW SE & ACT Wagga Wagga - Riverina and Western NSW 18/21 mary st unit 8/27 yallourn st (po box 62) suite 1, 39 fitzmaurice st (po box 5464) surry hills nsw 2010 (t 02 8202 8333) fyshwick act 2609 (t 02 6280 5053) wagga wagga nsw 2650 (t 02 6971 9696) Newcastle - Hunter and North Coast Bega - ACT and South East NSW Brisbane 1/54 hudson st 89-91 auckland st (po box 470) Suite 4, level 5 87 wickham terrace hamilton nsw 2303 (t 02 4929 2301) bega nsw 2550 (t 02 6492 8333) Spring hill qld 4000 (t 07 3129 7633) Document Verification Project Title: Braidwood Archaeological Management Plan, NSW Project Number: 17-446 Project File Name: Braidwood Archaeological Management Plan – Stage 1 (AZP) Revision Date Prepared by (name) Reviewed by (name) Approved by (name) FINAL 14.6.2018 Ingrid Cook and Jakob Ruhl Jakob Ruhl Matthew Barber NGH Environmental prints all documents on environmentally sustainable paper including paper made from bagasse (a by- product of sugar production) or recycled paper. NGH Environmental Pty Ltd (ACN: 124 444 622. ABN: 31 124 444 622). www.nghenvironmental.com.au e [email protected] Sydney Region Canberra - NSW SE & ACT Wagga Wagga - Riverina and Western NSW 18/21 mary st unit 8/27 yallourn st (po box 62) suite 1, 39 fitzmaurice st (po box 5464) surry hills nsw 2010 (t 02 8202 8333) fyshwick act 2609 (t 02 6280 5053) wagga wagga nsw 2650 (t 02 6971 9696) Newcastle - Hunter and North Coast Bega - ACT and South East NSW Brisbane 1/54 hudson st 89-91 auckland st (po box 470) Suite 4, level 5 87 wickham terrace hamilton nsw 2303 (t 02 4929 2301) bega nsw 2550 (t 02 6492 8333) Spring hill qld 4000 (t 07 3129 7633) CONTENTS ACRONYMS, ABBREVIATIONS AND DEFINITIONS .................................................................................. -

South-East Forests and Logging

MAGAZINE OF THE CONFEDERATION OF BUSHWALKING CLUBS NSW INC. ISSN 0313 2684 WINTER - MAY 2000 VOLUME 25 NO 4 http://www.bushwalking.org.au BUSHWALKING IN S OUTH-EAST FORESTS THE UNITED STATES Tom Boyle AND LOGGING T HE JOHN MUIR TRAIL Excerpt from NEWS RELEASE; John Macris Conservation Officer In the United States, bushwalking is Friday, 14 April 2000 importantly to protect endangered called hiking. There are three famous The Premier of NSW, Mr Bob Carr species from extinction in coming hiking trails in America: The Appala- today announced a major expansion of the decades. chian Trail, The Pacific Crest Trail and States national parks system of almost While the reservations of the past 5 The John Muir Trail. 324,000 hectares and a guaranteed 20 year years are measured in the hundreds of The Appalachian Trail extends log supply for the timber industry in the thousands of hectares, the data from from northern Georgia to Southern South Coast and Tumut regions. the assessment process would demon- Maine near the crest of the Appala- The Southern Forest Agreement, strate that these steps forward have chian Mountains on the eastern side of comprising the South Coast and Tumut been modest rather than momentous in the country. Compared to the isolation regions, represents a balanced decision based the scheme of things. of the other two trails, it is a social on three years of intensive scientific forest The figure of 324,000 hectares gathering. Approximately 3,400 research. protected under this decision, is kilometers long, the trail is host to It creates a approximately about 750 through hikers each year. -

Buckenbowra Pre Logging Jan 08 Buckenbowra Logged March 09

UPDATE ON LOGGING ACTIVITIES IN SOUTH COAST/SOUTHERN REGION MARCH 2009 Buckenbowra pre logging Jan 08 Buckenbowra logged March 09 The Southern Region runs from Nowra down to Cobargo and out to the Great Dividing Range. The unprotected State Forest areas total 200,000+ hectares. From the March IFOA report we see that there are currently 15 different compartments being logged in the area, totalling 3071 hectares. • Just south of Nowra, and very close to the coast, in the Jervis Bay Catchment, compartment 1040 of Currambene SF is being logged, we suspect that most of the wood goes to the big firewood yard near Tomerong, but a fair proportion would also be heading down to the Eden chip mill. • In the Clyde River Catchment four compartments are active: South Brooman 55 & 61, Currowan 222,and Yadboro 445. • In the Tomaga River Catchment compartment 186 of Mogo SF is undergoing the AGS treatment. AGS means ‘Australian Group Selection’ in stumpy-speak; but to a normal bush observer it means mini clear fells dotted through the compartment. This style of logging is quite new to the coastal zone but we expect it will become the norm as supplies for the chipper dwindle. • Wandera 586 has been active since 7may08, part of the ongoing logging of the eastern area of this SF in the Deua River Catchment area. Once done there we expect they will head out to the western side of Wandera into more contentious territory. • In the Tuross River Catchment there are four logging operations active: compartments 3020 and 3067 of Bodalla SF. -

Sydneyœsouth Coast Region Irrigation Profile

SydneyœSouth Coast Region Irrigation Profile compiled by Meredith Hope and John O‘Connor, for the W ater Use Efficiency Advisory Unit, Dubbo The Water Use Efficiency Advisory Unit is a NSW Government joint initiative between NSW Agriculture and the Department of Sustainable Natural Resources. © The State of New South Wales NSW Agriculture (2001) This Irrigation Profile is one of a series for New South Wales catchments and regions. It was written and compiled by Meredith Hope, NSW Agriculture, for the Water Use Efficiency Advisory Unit, 37 Carrington Street, Dubbo, NSW, 2830, with assistance from John O'Connor (Resource Management Officer, Sydney-South Coast, NSW Agriculture). ISBN 0 7347 1335 5 (individual) ISBN 0 7347 1372 X (series) (This reprint issued May 2003. First issued on the Internet in October 2001. Issued a second time on cd and on the Internet in November 2003) Disclaimer: This document has been prepared by the author for NSW Agriculture, for and on behalf of the State of New South Wales, in good faith on the basis of available information. While the information contained in the document has been formulated with all due care, the users of the document must obtain their own advice and conduct their own investigations and assessments of any proposals they are considering, in the light of their own individual circumstances. The document is made available on the understanding that the State of New South Wales, the author and the publisher, their respective servants and agents accept no responsibility for any person, acting on, or relying on, or upon any opinion, advice, representation, statement of information whether expressed or implied in the document, and disclaim all liability for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information contained in the document or by reason of any error, omission, defect or mis-statement (whether such error, omission or mis-statement is caused by or arises from negligence, lack of care or otherwise). -

Eurobodalla Regional

B CDFor adjoining map see Cartoscope's Shoalhaven Tourist Map TO ULLADULLA 17 km BIMBERAMALA RD NELLIGEN 35º30'S 150º10'E Nelligen Ck 150º00'E RD NAT PK SHEEP Mt Ingold's MAP 9 Budawang THE TRACK BIG4 NELLIGEN CITY Knob HOLIDAY PARK 0500250 BUDAWANG OF RD Creek SHALLOW Carters Metres River SOUTH BROOMAN REIDSDALE Remains of the CLYDE 52 Bushranger's MONGA Y Tree NAT PK CROSSING RA Lyons Shallow Crossing MUR NATIONAL PARK VALLEY RD (locality) RD ST BRAIDWOOD 50km BRAIDWOOD (Crossing impassable during RD TO CANBERRA 130km, heavy rains or high tide) BRAIDWOOD ST elec SHOALHAVEN R RD LA TALLAGANDAE P ST ST ST F 830 W Sugarloaf Mt STATE O JembaicumbeneC FOREST 836 Creek MAISIES CURROWAN STATE FOREST 820 CURROWAN BLVD WHARF D OLD ST R Creek ST TUDOR KINGS RD REID N E Clyde Mt G NELLIGEN I L MONGA L E 1 Cemetery SF 144 N 1 Creek D OL CANBERRA 103 km The RD LYONS RD Reidsdale MURRAMARANG TO BRAIDWOOD 22 km, CLYDE RD CL VIEW (creek East Lynne BRIDGE crossing) PEBBLY RD Monga 5 (locality)RD 7 RD The Logontoseedetailed Corn Creek Eucalypt BOYNE STATE FOREST RD Trail touring and holiday maps, Reidsdale CURROWAN 832 (locality) RD NATIONAL information and to purchase FLAT N River Misty Mountain, No Name & Bolaro Creek maps and guides. Roads are dry weather roads and RD MISTY TOMBOYE SHIRE © Copyright Cartoscope Pty Ltd should be avoided when wet. 52 BLACK RIVER PARK TO BATEMANS BAY 8km THORPES RD RD Pebbly Trail Clickonthe RIDGE MT Beach STATE FOREST 7 AGONY weblink below 820 RD River BIT to log on BIG 149º50'E 149º50'E Depot Nelligen Durras MONGA Mt Currowan Big Bit Discovery Beach THE Lookout Trail No Name Road is steep RD RD North Araluen Gate and eroded in sections. -

Canberra Bushwalking Club

Canberra Bushwalking Club P.O. Box 160, Canberra City - • // / -- REVEL IN 0cj in Volume 7 December 1971 Nuqther 12 Registered for posting as-a periodical - Category B. Price lOc. SPECIAL NOTICES There will be no General Meetingin December, but we look forward to seeing all survivors of the Festive Season in January. At the February meeting, slides of "exhibition quality" from Xmas/New Year trips will be shown. Vetting officer: John Hogan. LAST CHANCE ))-- Send your subscription ---3 PAT GREEN ($2.. singles; $3 doubles) P.O. Box 160 GOING CHEAP! .. CANBERRA CITY CANBERRA PRICES! (Persons with a red mark on their magazine wrapper are reminded that 'IT' will no longer be theirs unless they renew their subscription). RFNEWAL OF MEMBERSHIP NAME(S): ............................................................... ADDRESS ................................................................. • 1 TELEPHONE (HOME) ........................ -0• (woiuc) ....................... Weare I am enclosing ......................for membership 1971-72 SIGNATURE(S) ......... ...............,.... DATE - 2 - IT DECEMBER 1971 TIkADITIONAL FIGHTING EDITORIAL Plentrxthr& through scrub or sliding down scree, Scratched by each hush, knocked by each tree, Eaten by ants, dissolved by the sun, The newcomer asks himself - "Can this be fun?" TheprogItn1me said 1tEsy" - I thought t would be so - s rocks., thorns and climbs, and a long way to got My. shoesttsed to fit,.Mut they don't anymore; My knees are a-qüive:,nff shOulders are sore. I'd like to belong to your usftwa1king Club Butw3dno-ore warn me aht'ut-.a14: that scrub? T don t call this walkiinsp ic don't call this bush It s nothing but .jungland Sc ramble and rush. 0 Bushwal'cx ig Brethren plc sc Aped fly petition "Jut what is a bushwalk?. -

Palerang Final Report 2015

Final Report 2015 Palerang LGA 540 Date: 17 November 2015 FINAL REPORT PALERANG LGA 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OVERVIEW Palerang Local Government Area The Palerang Local Government area adjoins the Australian Capital Territory as well as seven NSW LGA’s comprising Yass Valley, and Queanbeyan City to the West, Eurobodulla Shire to the East, Shoalhaven to the Northeast, Goulburn-Mulwaree and Upper Lachlan to the North and Cooma-Monaro to the South. Morton, Budawang, Monga and Deua National Parks are located in the eastern portion, separating Palerang from the South Coast. Tallaganda State Forest and National Park is located South of Bungendore. The LGA covers an area of 5143 square km, and has a population of 14,835 ( 2011 census ). The topography is variable with valleys of flat to undulating arable lands running north/south alternating with steeper grazing slopes and bush covered hills. Palerang is predominantly a rural district as well as accommodating Canberra based workers. Farming is an important sector within the District although small holdings and hobby farms dominate in terms of numbers. Rural subdivision has resulted in many of the larger farm holdings being reduced in size. Productive farms make up a small fraction of the total property sales occurring. Palerang is a popular district with easy access to Canberra and Queanbeyan and to a lesser extent Goulburn, Sydney and the NSW South Coast. Batemans Bay is accessible via the Kings Highway, while Shoalhaven can be accessed via Nerriga Road. Land development within the district in the past has followed the traditional pattern of subdivision of farmland into rural/residential blocks and hobby farms with rural- residential subdivisions near Queanbeyan and the ACT. -

Eurobodalla Region

B CDFor adjoining map see Cartoscope's Shoalhaven Tourist Map TO ULLADULLA 17 km NELLIGEN BIMBERAMALA RD RD 35º30'S NAT PK 150º10'E NelligenNEATE Ck 150º00'E PARK SHEEP Mt Ingold's MAP 9 Budawang THE TRACK BIG4 NELLIGEN CITY Knob HOLIDAY PARK 0500250 BUDAWANG OF RD Creek SHALLOW Carters Metres River SOUTH BROOMAN REIDSDALE Remains of the CLYDE Bushranger's MONGA A1 Y ST Tree NAT PK CROSSING RA Lyons Shallow Crossing MUR B52 NATIONAL PARK VALLEY RD RD (locality) RD BRAIDWOOD 50km BRAIDWOOD (Crossing impassable during TO CANBERRA 130km, heavy rains or high tide) BRAIDWOOD elec SHOALHAVEN ST R RD LA TALLAGANDAE P ST ST ST F 830 W Sugarloaf Mt STATE O JembaicumbeneC FOREST 836 Creek MAISIES CURROWAN KINGS CURROWAN STATE FOREST 820 BLVD WHARF D OLD ST R Creek ST TUDOR KINGS RD REID N E Clyde Mt G NELLIGEN I L AIDWOOD 22 km, MONGA L E 1 N 1 Cemetery SF 144 Creek D OL The RD LYONS RD TO BR Reidsdale MURRAMARANG CLYDE RD CL VIEW (creek East Lynne BRIDGE crossing) PEBBLY RD Monga 5 HWY (locality)RD QUEANBEYAN97km,CANBERRA 103 km 7 RD The Corn Creek Eucalypt BOYNE STATE FOREST RD Trail Reidsdale CURROWAN 832 (locality) B52 RD NATIONAL FLAT BAY 8km N River Misty Mountain, No Name & Bolaro Creek Roads are dry weather roads and RD TO BATEMANS MISTY TOMBOYE SHIRE © Copyright Cartoscope Pty Ltd should be avoided when wet. BLACK RIVER PARK THORPES RD RD Pebbly Trail RIDGE MT Beach STATE FOREST 7 AGONY 820 RD River BIT BIG Durras Depot 149º50'E 149º50'E Nelligen MONGA Mt Currowan Big Bit Discovery Beach THE Lookout Trail No Name Road is steep RD RD North Araluen Gate and eroded in sections.