Variable Production of Annual Growth Rings by Juvenile Chelonians WILLIAM R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Municipal Solid Waste Management by Urban Local Bodies

CHAPTER 2 Performance Audit on “Municipal Solid Waste Management by Urban Local Bodies” Executive Summary Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) comprises residential and commercial wastes generated in a municipal area in either solid or semi-solid form excluding industrial hazardous wastes but including treated bio-medical wastes. The Government of India (GoI), in exercise of the powers conferred under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, had framed Municipal Solid Wastes (Management and Handling) Rules, 2000 (MSW Rules) to regulate the management and handling of MSW to protect and improve the environment and to prevent health hazards to human beings and other living creatures. As per MSW Rules, every municipal authority is responsible for collection, segregation, storage, transportation, processing and disposal of municipal solid wastes. A Performance Audit on Municipal Solid Waste Management (MSWM) was conducted covering 36 ULBs of ten districts for the period 2011-16. Significant audit observations are as follows: ● City plans were not prepared by the test checked ULBs but for NN Lucknow, NN Kanpur and NPP Sultanpur. Paragraph 2.6.1 ● Waste processing facilities were not sanctioned in 604 ULBs of the State. The facilities were operational in only 1.4 per cent of total ULBs. Out of 36 test checked ULBs, waste processing and disposal facilities was sanctioned only for seven, whereas only three of these were operational. Paragraph 2.6.2 ● Thirty five per cent (` 177.91 crore) of sanctioned cost (` 505.30 crore) of MSW management projects in the State remained unutilised as installation works of 19 MSW processing and disposal facilities were held up due to various reasons. -

Carrier Number Fluctuation and Mobility Inhigh Field Insulating Materials

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 CARRIER NUMBER FLUCTUATION AND MOBILITY INHIGH FIELD INSULATING MATERIALS WITH SHALLOW TRAPS AT LOW FREQUENCY PRADEEP SHARMA Sidharth Mahavidhyalay Ludhpura, Jaswantnagar, Etawah (India) Abstract- The analytical expressions for the low frequency noise resistance have been evaluated for the single injection current flow in insulator operating in high field regime in the complete range of current-voltage characteristic. It is shown that the complete noise characteristic is started from the carrier density fluctuations in ohmic regime at low injection level of current which is dominated by the space charge at high injection level above a critical point. Keywords – Noise resistance, single injection, current-voltage. I. INTRODUCTION The studies on the electrical conduction and noise behaviour for single injection current flow in insulator at high field have open the promising directions to develop the important devices by the workers (1-7). The noise source at low frequency in injection devices at high field is obtained from the fluctuations in carrier density and mobility described by Sharma (1974). It is observed by the workers of the field "that the mobility is dependent on the electric field strength above a critical field described by Nicolet,Bilger and Zijlstra (1) and Lampert and Mark (5)« The current flow is dominated by the space charge in single injection devices to give nonlinear effects on current-voltage and noise characteristics. II. GENERAL EQUATIONS -

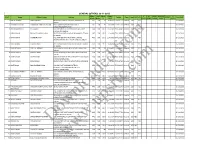

(OTHERS) 26-11-2018 Obtain Total Marks Date of a EX- ARDH MRATAK O S.NO

GENERAL (OTHERS) 26-11-2018 Obtain Total Marks Date of A EX- ARDH MRATAK O S.NO. Name Father's Name Address RefNo. Caste Amt NCC ITI RETIRE CALL DATE Marks Marks % Birth LEVEL ARMY SAINIK ASHRIT LEVEL 1 OMESH KUMAR RAM PRAKASH NEW BASTI, BANSHEEGOHARA, MAINPURI UP 465 500 93 16-Jul-93 ETW-19727 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 205001 2 SHIVAM CHAUHAN HANUMANT SINGH CHAUHAN POST GADHI RAMDHAN GADHI DALEL 465 500 93 1-Aug-00 ETW-21779 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 JASWANTNAGAR ETAWAH 3 ABHIMANYUSINGH RAJ KUMAR VILLAGE SARAY JALAL POST MANIYAMAU DIST 464 500 92.8 12-Jan-93 ETW-19384 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 ETAWAH PIN 206126 4 VIPIN KUMAR PRAKAS CHANDRA YADAV 33/623, SHAKUNTLA NAGAR, NEW MANDI, ETAWAH 463 500 92.6 4-Oct-89 ETW-19703 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 UP 206001 5 NITIN KUMAR AVDHESH SINGH VILL MUHABBATPUR POST SIRHAL TAHSIL 463 500 92.6 11-Feb-98 ETW-15582 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 JASWANTNAGAR DIST ETAWAH PINCODE 206245 6 VIVEK KUMAR KESHAV SINGH 229 FARRUKHABAD ROAD ASHOK NAGAR ETAWAH 462 500 92.4 10-Jul-90 ETW-19362 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 UP 206001 7 VIKAS PORWAL HOTI LAL PORWAL 310 KATRA BAL SINGH NEVIL ROAD ETAWAH PIN 460 500 92 30-Aug-86 ETW-19908 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 206001 8 SANJAY SINGH MANGAL SINGH LOHIYA WARD NO 6 VIDHUNA AURAIYA PIN CODE 458 500 91.6 2-Jul-98 ETW-18934 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 206243 from 9 AMIT KUMAR OM PRAKASH 186 JAIN MANDIR KE PAS KATRA FATEH MAHMOOD 456 500 91.2 10-Apr-88 ETW-20480 General 200 YES 26-11-2018 KHAN ETAWAH 206001 10 SANOJ KUMAR SURAJ SINGH ASHOK NAGAR, OLD PAC GALI, ETAWAH UP -

Royal Asiatic Society

LIST OF THE MEMBERS ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAKJ) FOUNDED MARCH, 1823 APEIL, 1929 74 GROSVENOK STKEET LONDON, W. 1 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.22, on 29 Sep 2021 at 03:25:44, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0035869X00069963 ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY Patron HIS MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY THE KING. Vice-Patrons HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCE OF WALES. FIELD-MARSHAL HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE DUKE OF CONNAUGHT. THE VICEROY OF INDIA. THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INDIA. Honorary Vice-Presidents 1925 THE RIGHT HON. LORD CHALMERS, P.O., G.C.B. 1925 SIR GEORGE A. GRIERSON, K.C.I.E., PH.D., D.LITT. 1919 REV. A. H. SAYCE, D.LITT., LL.D., D.D. 1922 LIEUT.-COL. SIR RICHARD C. TEMPLE, BART., C.B., C.I.E., F.S.A., F.B.A. COUNCIL OF MANAGEMENT FOR 1928-29 President 1928 THE MOST HON. THE MARQUESS OF ZETLAND, G.C.S.I., G.C.I.E. Director 1927 PROFESSOR D. S. MARGOLIOUTH, M.A., P.B.A., D.LITT. Vice-Presidents 1926 L. D. BARNETT, ESQ., M.A., LITT.D. 1925 L. C. HOPKINS, ESQ., I.S.O. 1925 PROFESSOR S. H. LANGDON, M.A., PH.D. 1928 SIR EDWARD MACLAGAN, K.C.S.I., K.C.I.E. Honorary Officers 1928 SIR J. H. STEWART LOCKHART, K.C.M.G., LL.D. (Hon. Secretary). 1928 E. S. M. PEROWNE, ESQ., F.S.A. -

Notice for Appointment of Regular/Rural Retail Outlets Dealerships

Notice for appointment of Regular/Rural Retail Outlets Dealerships Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in the State of Uttar Pradesh, as per following details: Fixed Fee Minimum Dimension (in / Min bid Security Estimated Type of Finance to be arranged by the Mode of amount ( Deposit ( Sl. No. Name Of Location Revenue District Type of RO M.)/Area of the site (in Sq. Site* applicant (Rs in Lakhs) selection monthly Sales Category M.). * Rs in Rs in Potential # Lakhs) Lakhs) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 SC/SC CC 1/SC PH/ST/ST CC Estimated Estimated fund 1/ST working required for PH/OBC/OBC CC/DC/ capital Draw of Regular/Rural MS+HSD in Kls Frontage Depth Area development of CC 1/OBC CFS requirement Lots/Bidding infrastructure at PH/OPEN/OPE for operation RO N CC 1/OPEN of RO CC 2/OPEN PH ON LHS, BETWEEN KM STONE NO. 0 TO 8 ON 1 NH-AB(AGRA BYPASS) WHILE GOING FROM AGRA REGULAR 150 SC CFS 40 45 1800 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 MATHURA TO GWALIOR UPTO 3 KM FROM INTERSECTION OF SHASTRIPURAM- VAYUVIHAR ROAD & AGRA 2 AGRA REGULAR 150 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 BHARATPUR ROAD ON VAYU VIHAR ROAD TOWARDS SHASTRIPURAM ON LHS ,BETWEEN KM STONE NO 136 TO 141, 3 ALIGARH REGULAR 150 SC CFS 40 45 1800 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 ON BULANDSHAHR-ETAH ROAD (NH-91) WITHIN 6 KM FROM DIBAI DORAHA TOWARDS 4 NARORA ON ALIGARH-MORADABAD ROAD BULANDSHAHR REGULAR 150 SC CFS 40 45 1800 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 (NH 509) WITHIN MUNICIAPL LIMITS OF BADAUN CITY 5 BUDAUN REGULAR 120 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 ON BAREILLY -

List of Common Service Centres Established in Uttar Pradesh

LIST OF COMMON SERVICE CENTRES ESTABLISHED IN UTTAR PRADESH S.No. VLE Name Contact Number Village Block District SCA 1 Aram singh 9458468112 Fathehabad Fathehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 2 Shiv Shankar Sharma 9528570704 Pentikhera Fathehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 3 Rajesh Singh 9058541589 Bhikanpur (Sarangpur) Fatehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 4 Ravindra Kumar Sharma 9758227711 Jarari (Rasoolpur) Fatehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 5 Satendra 9759965038 Bijoli Bah Agra Vayam Tech. 6 Mahesh Kumar 9412414296 Bara Khurd Akrabad Aligarh Vayam Tech. 7 Mohit Kumar Sharma 9410692572 Pali Mukimpur Bijoli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 8 Rakesh Kumur 9917177296 Pilkhunu Bijoli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 9 Vijay Pal Singh 9410256553 Quarsi Lodha Aligarh Vayam Tech. 10 Prasann Kumar 9759979754 Jirauli Dhoomsingh Atruli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 11 Rajkumar 9758978036 Kaliyanpur Rani Atruli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 12 Ravisankar 8006529997 Nagar Atruli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 13 Ajitendra Vijay 9917273495 Mahamudpur Jamalpur Dhanipur Aligarh Vayam Tech. 14 Divya Sharma 7830346821 Bankner Khair Aligarh Vayam Tech. 15 Ajay Pal Singh 9012148987 Kandli Iglas Aligarh Vayam Tech. 16 Puneet Agrawal 8410104219 Chota Jawan Jawan Aligarh Vayam Tech. 17 Upendra Singh 9568154697 Nagla Lochan Bijoli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 18 VIKAS 9719632620 CHAK VEERUMPUR JEWAR G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 19 MUSARRAT ALI 9015072930 JARCHA DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 20 SATYA BHAN SINGH 9818498799 KHATANA DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 21 SATYVIR SINGH 8979997811 NAGLA NAINSUKH DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 22 VIKRAM SINGH 9015758386 AKILPUR JAGER DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 23 Pushpendra Kumar 9412845804 Mohmadpur Jadon Dankaur G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 24 Sandeep Tyagi 9810206799 Chhaprola Bisrakh G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. -

1 Village Kathera, Block Akrabad, Sasni to Nanau Road , Tehsil Koil

Format for Advertisement in Website Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited (BPCL) proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in Uttar Pradesh, as per following details: Fixed Fee / Security Estimated monthly Type of Minimum Dimension (in M.)/Area of Mode of Minimum Bid Sl. No Name of location Revenue District Type of RO Category Finance to be arranged by the applicant Deposit (Rs. Sales Potential # Site* the site (in Sq. M.). * Selection amount (Rs. In In Lakhs) Lakhs) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 SC, SC CC-1, SC PH ST, ST CC-1, ST PH OBC, OBC CC- CC / DC / Estimated fund Estimated working Draw of Regular / 1, OBC PH CFS required for MS+HSD in Kls Frontage Depth Area capital requirement Lots / Rural development of for operation of RO Bidding infrastructure at RO OPEN, OPEN CC- 1, OPEN CC- 2,OPEN-PH Village Kathera, Block Akrabad, Sasni to Nanau Road , Draw of 1 Tehsil Koil, Dist Aligarh ALIGARH RURAL 90 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Dhansia, Block Jewar, Tehsil Jewar,On Jewar to GAUTAM BUDH Draw of 2 Khurja Road, dist GB Nagar NAGAR RURAL 160 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Dewarpur Pargana & Distt. Auraiya Bidhuna Auraiya Draw of 3 Road Block BHAGYANAGAR AURAIYA RURAL 150 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Kudarkot on Kudarkot Ruruganj Road, Block Draw of 4 AIRWAKATRA AURAIYA RURAL 100 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 5 Village Behta Block Saurikh on Saurikh to Vishun Garh Road KANNAUJ RURAL 100 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 6 Village Nadau, -

Census 1971 I I ~ Part X-A Town & Village Directory J I Series 21 I Uttar Pradesh I I ·1 ?:2.L(831

CENSUS 1971 I I ~ PART X-A TOWN & VILLAGE DIRECTORY J I SERIES 21 I UTTAR PRADESH I I ·1 ?:2.L(831. I l I j DISTRICT DISTRICT I ETAWAH CENSUS 1 HANDBOOK D. M. SINHA, IIi OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATlVE SFRV1CE I Director of Census Operations I Uttar Pradesh "PIUCE : 'itS. 14.~ CONTENTS fag4s Ac.lmowbig,-mcnts i Introductory Note hi-xiii TOWN AND VILLAGE DlRECTOllY Town Directory Statement I-Status, Growth History and Functional Category of Towns 4-5 Statement II-Physical Aspects and Location of Towns 1969 4-5 Statement III-Municipal Finance 1968-69 4-5 Statement IV-Civic and other Amenities 1969 6-7 Statement V-Medical, Educational, Recreational and Cultural FacUities in Towns 1969 -6-7 Statement VI-Trad'c, Commerce, Industry, and Banking, 1969 6-] Statement VII-Population by Religion and Schedllled Castes/Shcduled Tribes., 1971 8 Village Directory l-Etawah Tahsil (i) Alphabetical List ,of Villages 1~-15 (1i) Village Directory (Amenities and laud use) 16-45 2-Bharthana Tahsil (i) Alphabetical List of Villages 49-51 (li) Village Directory (Amenities and land use) 52-77 S-Bidhuna Tahsil 80-83 (i) Alphabetical List or Villages (Ii) Village Directory (Amenities and la.nd use) 84-1l!) f-Auraiya Tahsil (1) Alphabetica.l List of Villages 122-125 (Ii) Village Directory (Amenities and land use) .126-161 4ppendi&-Tahsilwlse Abstract of Educatlnal, Medical" a~d other Amenities given in Village Directory 162 .... 163 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS At the 1971 Census it has been our endeavour to compile both Census and non-Censu8 statistics at the Village and Block level in a uniform mannel. -

Etawah Page:- 1 Cent-Code & Name Exam Sch-Status School Code & Name #School-Allot Sex Part Group 1002 S G P V S K I C Bijpuri Khera Etawah Brm

DATE:27-02-2021 BHS&IE, UP EXAM YEAR-2021 **** FINAL CENTRE ALLOTMENT REPORT **** DIST-CD & NAME :- 41 ETAWAH PAGE:- 1 CENT-CODE & NAME EXAM SCH-STATUS SCHOOL CODE & NAME #SCHOOL-ALLOT SEX PART GROUP 1002 S G P V S K I C BIJPURI KHERA ETAWAH BRM HIGH BRM 1002 S G P V S K I C BIJPURI KHERA ETAWAH 82 F HIGH CRM 1095 DR.NAIPAL SINGH INTER COLLEGE DUNGARI ETAWAH 29 M HIGH CRM 1095 DR.NAIPAL SINGH INTER COLLEGE DUNGARI ETAWAH 14 F HIGH CRM 1104 SANT K P RAMANUJ DAS I C BAIDPUR ETAWAH 40 M HIGH CRF 1123 M A B G H S SCHOOL NAGALA KHERA ETAWAH 27 M HIGH CRF 1123 M A B G H S SCHOOL NAGALA KHERA ETAWAH 18 F HIGH CUM 1169 BLUE BIRD I C RATAN NAGAR ETAWAH 25 M HIGH CUM 1203 VIKAS MEMORIAL INTER COLLEGE SHANTI COLONY ETAWAH 11 F HIGH CUM 1203 VIKAS MEMORIAL INTER COLLEGE SHANTI COLONY ETAWAH 10 M HIGH CUM 1252 ADARSH SANT KHEMDAS P UMV PANDUNAGAR KACHAURA ROAD ETAWAH 10 M HIGH CUM 1276 SHRI RAGHUVAR DAYAL MEMO HIGH SCHOOL SARAY DAYANAT ETAWAH 35 M HIGH CRM 1294 L S U M V RAJMAU ETAWAH 32 F HIGH CRM 1294 L S U M V RAJMAU ETAWAH 41 M 374 INTER BRM 1002 S G P V S K I C BIJPURI KHERA ETAWAH 27 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER BRM 1002 S G P V S K I C BIJPURI KHERA ETAWAH 64 F SCIENCE INTER CRM 1095 DR.NAIPAL SINGH INTER COLLEGE DUNGARI ETAWAH 15 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRM 1095 DR.NAIPAL SINGH INTER COLLEGE DUNGARI ETAWAH 28 M OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRM 1104 SANT K P RAMANUJ DAS I C BAIDPUR ETAWAH 19 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRM 1104 SANT K P RAMANUJ DAS I C BAIDPUR ETAWAH 3 M OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CUM 1203 VIKAS MEMORIAL INTER COLLEGE SHANTI COLONY -

State-Wise Length of National Highways (NH) in India As on 30.11.2018 1/31

State-wise length of National Highways (NH) in India as on 30.11.2018 1/31 Sl. NH No. State / U.T. Route Length No. (km) Andhra Pradesh 1 16 5, 6, 60 & 217 Orissa-Anandapuram Pendurthi, Anakapalli, Rajahmundary, Deverapalli, Gondugolanu,Vijayawada, Nellore-Tamil 1,024.1 Nadu Border // Anandapuramu-Visakhapatnam-Anakapalli 2 216 214, 214A Junction with NH-16 near Kathipudi - Kakinada, Machilipatnam - junction with NH-16 near Ongole 391.3 3 216A 16 GQ Rajamahendravaram - tanuku - Tadepalli gudem- Gundugolanu 120.7 4 516C The highway starting from its junction with NH-16 at Sabbavaram bypass connecting Amruthapuram, Narava, 12.7 Sathivani palem, Gopalpatanam rural and terminating near Sheelanagar in the State of Andhra Pradesh. 5 516D Junction with NH 16 near Deverapalli Bypass - Golladgudem, Gopalapuram, Jaganathapuram, Atchyutapuram, 57.7 Koyyalgudem, Bayyanagudem, Seetampeta, Narasannapalem, Jangareddigudam, Vegavaram, Taduvai, Darbhagudem- Jeelugumilli near Andhra Pradesh/Telengana border. 6 516 E junction with NH No. 16 near Rajamundry - Bhupatiapalem Road (connecting SH-38 near Rampachodavaram), 406.2 Koyyuru, Chintapalli, Lambasingi, Paderu, Aruku, Bowadara, Tadipudi - junction of NH-26 at Vizianagaram 7 716 205 Tamil Nadu Border-Reniguta, Mamanduru, Settigunta, Koduru, Pullampeta, Rajampet, Nandalur, Madhavaram, 237.8 Vonimitta, Bhakarapet, Kadapa (Cuddapah), Kuarunipalli, Vellore, Thapetla, Kothapalli, Chidipirala, Pandillapalle, Thiparulu, Yeragunttla, Nidizivve, Chillamakuru , and terminating at its junction with NH-67 near Muddanuru 8 716A Junction with NH-716 near Puttur connecting , Narayana Vanam, Thumburu, Koppedu, Harijan, Vada, Ramagiri, 42.6 Krishnapuram, Utthukottai -Tamil Nadu. 9 716B The highway starting from its junction with NH-16 near Thachur in the state of Tamil Nadu and terminating at its 20.0 junction with NH-40 near Chittoor in the state of Andhra Pradesh. -

Designation Mobile No Office Phone Res. Phone Posting Place

3/9/2015 CUG NO Details BACK Home Print Close Please choose your Sorting For Full List option /Search Option : Designation Mobile No Office Phone Res. Phone Posting Place To Search a Name of the Post (Officer Particular BDO Full List Designation) Designation To Search a Particular Name Enter min 3 char. of Designation/Mobile No/Office Phone/Res. Phone/Posting Place Search CUG Office Residence S.No. Division District Officer Designation Fax No Posting Place Mobile No Phone Phone 1 AGRA MATHURA BDO Nandgaon 9454464521 NanadGaon 2 AGRA MATHURA BDO chhata 9454464522 Chhata 3 AGRA MATHURA BDO Chaumuha 9454464523 Chaumuha 4 AGRA MATHURA BDO Naujhil 9454464524 Naujhil 5 AGRA MATHURA BDO Mant 9454464525 Mant 6 AGRA MATHURA BDO Raya 9454464526 Raya 7 AGRA MATHURA BDO Goverdhan 9454464527 Goverdhan 8 AGRA MATHURA BDO Mathura 9454464528 Mathura 9 AGRA MATHURA BDO Mathura 9454464528 Mathura 10 AGRA MATHURA BDO Farah 9454464529 Farah 11 AGRA MATHURA BDO Farah 9454464529 Farah 12 AGRA MATHURA BDO Baldeo 9454464530 Baldeo Mathura 13 AGRA FEROZABAD BDO 9454464496 0 0 0 Firozabad 14 AGRA FEROZABAD BDO 9454464498 0 0 0 Eka 15 AGRA FEROZABAD BDO 9454464502 0 0 0 Jasarana 16 AGRA FEROZABAD BDO 9454464504 0 0 0 Araw 17 AGRA FEROZABAD BDO 9454464505 0 0 0 Madanpur 18 AGRA FEROZABAD BDO 8004418144 0 0 0 Araw 19 AGRA FEROZABAD BDO 9411411519 0 0 0 Jasarana 20 AGRA FEROZABAD BDO 9556266188 0 0 0 Eka 21 AGRA FEROZABAD BDO 9557340940 0 0 0 Shikohabad 05672 22 AGRA MAINPURI BDO Mainpuri 9410675800 Block MAINPURI 235844 05672 23 AGRA MAINPURI BDOKURAWALI 9415609022 -

Etawah Dealers Of

Dealers of Etawah Sl.No TIN NO. UPTTNO FIRM - NAME FIRM-ADDRESS 1 09128700005 EW0010599 RAM NATH PREM BEHARI K A ETAWAH 2 09128700010 EW0003354 M.PRASHAD,R.DAYAL JASWANT NAGAR ETAWAH 3 09128700019 EW0004862 JANTA SHOE STORE ETAWAH 4 09128700024 EW0029559 HAR PRASAD ANIL KUMAR K A ETAWAH 5 09128700038 EW0035677 MILAN MEDICAL STORE H.ROAD ETAWAH 6 09128700043 EW0041428 BHARTIYA PUSTAK BHANDAR BAJAJ LINE ETAWAH 7 09128700057 EW0044167 MURARI LAL,MAHESH CHANDRA JASWANT NAGAR ETAWAH 8 09128700062 EW0043650 NAVAL KISHOR SANDEEP KUMAR JASWANT NAGAR ETAWAH 9 09128700076 EW0049727 MURALI MANOHAR AND SONS PAKKI SARAI ETAWAH 10 09128700081 EW0050959 EXECUTIVE ENGG JAL NIGAM ETAWAH 11 09128700095 EW0055186 RAGHVENDRA SINGH ARMS ETAWAH 12 09128700104 EW0062257 DEVKI NANDAN MAHAVIR SINGH JASWANT NAGAR ETAWAH 13 09128700118 EW0060467 BHANU PRAKASH CONTRACTOR ETAWAH 14 09128700123 EW0060860 RAM CHARAN LAL BHAJAN LAL ETAWAH 15 09128700137 EW0061926 RASMI LOCK JANRAL STORE ETAWAH 16 09128700142 EW0065644 DAYA SWAROOP CHAURASIA ETAWAH 17 09128700156 EW0067887 GUPTA MACHINERY STORE SABIT GANJ ETAWAH 18 09128700161 EW0069616 ASHIARFI CONTRAUCTION CO 19 JATPURA ETAWAH 19 09128700175 EW0072687 LALU KIRANA STORE ETAWAH 20 09128700180 EW0076004 VARMA FURNITURE NEAR PRAKASH CINEMA ETAWAH 21 09128700189 EW0072549 S.M PANDAY AND CO. ETAWAH 22 09128700194 EW0073196 SRI AUTO MOBAILES DRIM LAND ETAWAH 23 09128700203 EW0074529 KUNJI LAL ,KAILASH NARAIN HOME GANJ ETAWAH 24 09128700217 EW0074833 DAEVESH READYMADE STORE 07 NAGAR PALIKA BAZAR ETAWAH 25 09128700222 EW0074971 PRAMOD EMPORIUM BHATELE MARKET 26 09128700236 EW0075443 NATIONAL PIPE INDS. ETAWAH 27 09128700241 EW0075860 SAIN SAKTI INT BHATTA ETAWAH 28 09128700255 EW0071277 ASHOK ELECTRIC CO STATION ROAD ETAWAH 29 09128700260 EW0076914 GAYA PRASHAD,KISHORI LAL ETAWAH 30 09128700269 EW0077309 SAURABH ELECTRONICS ETAWAH 31 09128700274 EW0072019 SUSHIL KUMAR BROTHERS ETAWAH 32 09128700288 EW0078207 PARAS ENT BHATTA STATION RD.