Taxation of Foundations in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tax Wedge in Croatia, Austria, Hungary, Poland and Greece

Tax wedge in Croatia, Austria, Hungary, Poland and Greece MARIN ONORATO, mag. math* Preliminary communication** JEL: H21, H24, J38 doi: 10.3326/fintp.40.2.5 * The author would like to thank two anonymous referees for their useful comments and suggestions. This article belongs to a special issue of Financial Theory and Practice, which is devoted to the comparison of tax wedge on labour income in Croatia and other EU countries. The articles in this issue have arisen from the students’ research project, undertaken in 2015. The Preface to the special issue (Urban, 2016) outlines the motivation behind the research project, explains the most important methodological issues, and reviews the literature on the measurement of tax wedge in Croatia. ** Received: January 31, 2016 Accepted: March 31, 2016 Marin ONORATO e-mail: [email protected] Abstract 266 The aim of this paper is to compare the tax burden on labour income in Croatia, Austria, Greece, Hungary and Poland in 2013. The Taxing Wages methodology has been applied to hypothetical units across a range of gross wages in order to calculate net average tax wedge, net average tax rate, as well as other relevant 40 (2) 265-288 (2016) PRACTICE FINANCIAL indicators. When it comes to single workers without children, the smallest tax wedge for workers earning less than the average gross wage was found in Croa- THEORY tia, while Poland had the smallest tax wedge for above-average wages. Due to a progressive PIT system, the tax wedge for a single worker in Croatia reaches 50% AND at 400% of the average gross wage, equalling that of Austria, Greece and Hun- gary. -

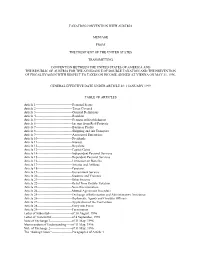

Taxation Convention with Austria Message from The

TAXATION CONVENTION WITH AUSTRIA MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING CONVENTION BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME, SIGNED AT VIENNA ON MAY 31, 1996. GENERAL EFFECTIVE DATE UNDER ARTICLE 28: 1 JANUARY 1999 TABLE OF ARTICLES Article 1----------------------------------Personal Scope Article 2----------------------------------Taxes Covered Article 3----------------------------------General Definitions Article 4----------------------------------Resident Article 5----------------------------------Permanent Establishment Article 6----------------------------------Income from Real Property Article 7----------------------------------Business Profits Article 8----------------------------------Shipping and Air Transport Article 9----------------------------------Associated Enterprises Article 10--------------------------------Dividends Article 11--------------------------------Interest Article 12--------------------------------Royalties Article 13--------------------------------Capital Gains Article 14--------------------------------Independent Personal Services Article 15--------------------------------Dependent Personal Services Article 16--------------------------------Limitation on Benefits Article 17--------------------------------Artistes and Athletes Article 18--------------------------------Pensions Article 19--------------------------------Government Service Article 20--------------------------------Students -

COMMISSION DECISION of 9 March 2004 on an Aid Scheme

22.7.2005EN Official Journal of the European Union L 190/13 COMMISSION DECISION of 9 March 2004 on an aid scheme implemented by Austria for a refund from the energy taxes on natural gas and electricity in 2002 and 2003 (notified under document number C(2004) 325) (Only the German version is authentic) (Text with EEA relevance) (2005/565/EC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, (5) By letter dated 4 July 2003, registered as received by the Commission on the same day (A/34759), Austria commented on the initiation of the procedure. Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, and in particular Article 88(2) thereof, (6) The Commission received comments from the Austrian Industry Association (Vereinigung der österreichischen Having regard to the Agreement on the European Economic Industrie) on 12 August 2003, from Stahl- und Area, and in particular Article 62(1)(a) thereof, Walzwerk Marienhütte GmbH on 18 August 2003 and from Jungbunzlauer GmbH on 14 August 2003. Comments from the Austrian Chamber of Labour (Bundesarbeitskammer) were withdrawn by letter dated Having called on interested parties to submit their comments 21 November 2003. pursuant to the provisions cited above (1) and having regard to their comments, 3 Whereas: (7) All comments were received in time ( ). The Commission forwarded them to Austria, which made no comments on these submissions. I. PROCEDURE (1) On 8 October 2002, Law No 158/2002 was published in the Austrian Official Journal. Its Article 6 modifies the (8) By letter dated 5 December 2003, registered as received Energy Tax Rebate Act 1996. -

Program of the New Austrian Government: Planned Tax Changes

No. 01/2020| 14 January 2020 International Tax Review Current information on international tax developments provided by EY Austria Program of the new Austrian government: planned tax changes On 2 January 2020, the new Austrian government formed by the conservative Austrian People’s Party and the Green Party presented its Content governmental program for the period 2020 to 2024. The new government commits itself to a balanced budget and to reduce state debt to the 01 Program of the new Austrian Maastricht treaty objective of 60%. Austria shall become climate-neutral government: planned tax changes until 2040. 02 Reporting obligations for The new government announced to develop a tax reform to reduce the certain payments under Sec. 109b Austrian Income Tax overall tax burden for people and to bring truth to ecological costs in the Act overall tax system. The program underlines to reduce the overall tax ratio to 40%, to introduce a both ecologic and social tax reform with steering 03 OECD Developments effects to fight against climate change, to expand innovative capacity, 03 EU Developments sustainability and competitiveness of the Austrian economy. 03 Country Updates There is the plan to reduce flat corporate income tax from currently 25% to 21%, without providing a timetable. As background information, on 30 April 2019, the former Austrian government announced its plans to reduce the corporate income tax in two stages in 2022 from 25% to 23% and in 2023 from 23% to 21%. Based on recent comments from government officials, a substantial reduction of the corporate income tax rate already in 2021 does not have priority for the new government and is expected in later years of the legislative period 2020 to 2024. -

Tax Wedge in Croatia, Austria, Hungary, Poland and Greece

Tax wedge in Croatia, Austria, Hungary, Poland and Greece MARIN ONORATO, mag. math* Preliminary communication** JEL: H21, H24, J38 doi: 10.3326/fintp.40.2.5 * The author would like to thank two anonymous referees for their useful comments and suggestions. This article belongs to a special issue of Financial Theory and Practice, which is devoted to the comparison of tax wedge on labour income in Croatia and other EU countries. The articles in this issue have arisen from the students’ research project, undertaken in 2015. The Preface to the special issue (Urban, 2016) outlines the motivation behind the research project, explains the most important methodological issues, and reviews the literature on the measurement of tax wedge in Croatia. ** Received: January 31, 2016 Accepted: March 31, 2016 Marin ONORATO e-mail: [email protected] Abstract 266 The aim of this paper is to compare the tax burden on labour income in Croatia, Austria, Greece, Hungary and Poland in 2013. The Taxing Wages methodology has been applied to hypothetical units across a range of gross wages in order to calculate net average tax wedge, net average tax rate, as well as other relevant 40 (2) 265-288 (2016) PRACTICE FINANCIAL indicators. When it comes to single workers without children, the smallest tax wedge for workers earning less than the average gross wage was found in Croa- THEORY tia, while Poland had the smallest tax wedge for above-average wages. Due to a progressive PIT system, the tax wedge for a single worker in Croatia reaches 50% AND at 400% of the average gross wage, equalling that of Austria, Greece and Hun- gary. -

Tax Aspects of Industrial Investment in Austria

Invest in Austria TAX ASPECTS OF INDUSTRIAL INVESTMENT IN AUSTRIA compiled by for AUSTRIAN BUSINESS AGENCY March 2011 www.investinaustria.at Impressum: Version: March 2011 Publisher: Austrian Business Agency, Opernring 3, A-1010 Vienna Responsible for content: PwC Vienna Editors: Johannes Mörtl, Rudolf Krickl Layout: creaktiv.biz – Karin Rosner-Joppich Print: Offset5020 www.investinaustria.at Contents Foreword 5 1. Overview 6 1.1 Taxation of corporate income ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������6 1.2 Taxation of individuals ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������6 1.3 Other taxes ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������6 2. Taxation of corporations 7 2.1 General provisions ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������7 2.2 Scope of tax liability ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������7 2.3 Tax rates and tax deductions ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������7 -

Tax and Investment Facts a Glimpse at Taxation and Investment in Austria 2019

Austria Tax and Investment Facts A Glimpse at Taxation and Investment in Austria 2019 Hungary Table of Contents 1 Ways of Doing Business / Legal Forms of Companies 4 2 Corporate Taxation 6 3 Double Taxation Agreements 18 4 Transfer Pricing 20 5 Anti-avoidance Measures 22 6 Taxation of Individuals / Social Security Contributions 24 7 Indirect Taxes 34 8 Inheritance and Gift Tax 37 9 Wealth Tax 37 Tax and Investment Facts 2019 x Austria 3 1 Ways of Doing Business / Legal Forms of Companies Austrian legislation offers various types of legal entity for com- Commonly used companies/legal entities for doing business in panies or private persons to perform their business in Austria. Austria are: Individuals may perform their business as sole proprietors or establish a legal entity. Foreign entrepreneurs or business entities → General partnership (Offene Gesellschaft, OG) are also able to establish a branch office (Zweigniederlassung) → Limited partnership (Kommanditgesellschaft, KG) in Austria. → Private limited liability company (Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung, GmbH) → Public limited liability company/Joint stock company (Aktien- gesellschaft, AG) Legal Form Liability of Minimum Minimum Registration Tax Tax Shareholder Capital (EUR) number of in Commercial Treatment Rates Founders and Register Shareholders Sole no shares, 1 Obligatory, if annual Tax liability of 0-55% proprietor personal turnover exceeds sole proprietor liability of the EUR 700,000 in two sole proprietors consecutive years General unlimited 2 Obligatory Transparent, -

The Tax Book 2019

The Tax Book 2019 Tips for employee tax assessment 2018 The Tax Book 2019 Tips for employee tax assessment 2018 Vienna 2018 Note The wage tax guidelines (these can be considered a summary of the current wage tax legislature and thus as a reference for administration and operational practice) are referenced in the text with margin numbers (“Rz” for German “Randzahl”, with “f” or “ff” for “et seq”). The wage tax guidelines as well as relevant ordinances and decrees can be found also at www.bmf.gv.at in section “Findok”. Imprint Issuer, owner and publisher: Bundesministerium für Finanzen (Federal Ministry of Finance), Public Relations, Communication and Protocol Johannesgasse 5, A-1010 Vienna, Austria www.bmf.gv.at Responsible for the information contained herein: BMF, Directorates General I and IV Translated into English by Cruz Communications GmBH, Vienna Graphics: Inga Seidl Werbeagentur Photos: colourbox.de Printed by: Printing Office of the Austrian Federal Ministry of Finance Copy date: October 2018 Vienna, November 2018 -– PrintedPrinted according according to theto theAustrian Austrian Ecolabel Ecolabel criteria for for printed printed matter, matter, Printing Printing Office Office of the of the Austrian Federal Federal Ministry Ministry of Finance, of Finance, UW-Nr. UW-Nr. 836 836 Further information can be found also at www.facebook.com/finanzministerium Contents I. General information on wage tax and income tax ........................................ 7 A. Personal liability to pay tax ............................................................................................. -

Austrian Taxation of the Income of a Foreign Citizen

Tibor Varga / Erich Wolf*) Austrian Taxation of the Income of a Foreign Citizen ÖSTERREICHISCHE BESTEUERUNG DES EINKOMMENS EINES AUSLÄNDISCHEN STAATSBÜRGERS Bei internationalen Steuerfällen muss genau zwischen innerstaatlichem (Außen-)Steuerrecht und DBA-Recht unterschieden werden. Die Autoren behandeln zunächst exemplarisch einen in der Praxis häufig vorkommenden Fall eines ausländischen Staatsbürgers mit steuerlichen Anknüpfungspunkten in Österreich. Der nachfolgende Aufsatz gibt eine praktische Anleitung für die abgabenrechtliche Würdigung. 1. Assumed Facts 1.1. Alternative A A Russian citizen („A") lives with his family in Russia. He comes to Vienna only from time to time and resides in various hotels. He is a shareholder of an Austrian limited liability company („GmbH") and has a residence permit for Austria. A is also a shareholder of Russian companies und he derives additional income from services rendered in Russia on a (self-)employed basis. 1.2. Alternative B A and his family live half of the time in Austria and half of the time in Russia. He maintains a home in both Russia and Austria. A derives income from the sources as specified in Alternative A. 2. Unlimited Tax Liability in Austria Individuals resident in Austria are subject to Austrian income tax on their worldwide income („unlimited tax liability"). A person is regarded as a resident of Austria if he has a permanent home („Wohnsitz") available to him or if he has his habitual abode („gewöhnlicher Aufenthalt") in Austria (section 1 of the Austrian Income Tax Code - „EStG"). A residence permit is not considered a relevant criterion but merely an indication of the existence of a permanent home or a habitual abode.1) A permanent home of an individual for purposes of tax law is defined as premises which such an individual uses under circumstances that imply that he will use and maintain the premises on an ongoing basis (section 26 paragraph 2 of the Austrian Federal Fiscal Code - „BAO"). -

The Tax Book 2021

The Tax Book 2021 Tips for employee tax assessment 2020 for wage taxpayers The Tax Book 2021 Tips for employee tax assessment 2020 for wage taxpayers Vienna 2020 Note Throughout the brochure, the female gender is included into the wording, as far as this is possible without impairing intelligibility of the contents. However, it is expressly emphasised that all statements written down using only the male form apply to females as well. The wage tax guidelines (these can be considered a summary of the current wage tax legislature and thus as a reference for administration and operational practice) are referenced in the text with margin numbers (“Rz” for German “Randzahl”, with “f” or “ff” for “et seq”). The wage tax guidelines as well as relevant ordinances and decrees can be found also at findok.bmf.gv.at. Imprint Issuer, owner and publisher: Bundesministerium für Finanzen (Federal Ministry of Finance), Public Relations, Communication and Protocol Johannesgasse 5, A-1010 Vienna, Austria www.bmf.gv.at Responsible for the information contained herein: BMF, Directorates General I and IV Graphics: Inga Seidl Werbeagentur Photos: Adobe Stock Printed by: Printing Office of the Austrian Federal Ministry of Finance Copy date: October 2020 Vienna, November 2020 -– PrintedPrinted according according to theto theAustrian Austrian Ecolabel Ecolabel criteria for for printed printed matter, matter, Printing Printing Office Office of the of the Austrian Federal Federal Ministry Ministry of Finance, of Finance, UW-Nr. UW-Nr. 836 836 Further information can be found also at www.facebook.com/finanzministerium Contents I. General information on wage tax and income tax ......................................7 A. -

AUSTRIA 2007 Review INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY

INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY Energy Policies of IEA Countries Please note that this PDF is subject to specific restrictions that limit its use and distribution. The terms and conditions are available online at www.iea.org/Textbase/about/copyright.asp AUSTRIA 2007 Review INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY The International Energy Agency (IEA) is an autonomous body which was established in November 1974 within the framework of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to implement an inter national energy programme. It carries out a comprehensive programme of energy co-operation among twenty-seven of the OECD thirty member countries. The basic aims of the IEA are: n To maintain and improve systems for coping with oil supply disruptions. n To promote rational energy policies in a global context through co-operative relations with non-member countries, industry and inter national organisations. n To operate a permanent information system on the international oil market. n To improve the world’s energy supply and demand structure by developing alternative energy sources and increasing the effi ciency of energy use. n To promote international collaboration on energy technology. n To assist in the integration of environmental and energy policies. The IEA member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Republic of Korea, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom and United States. Poland is expected to become a member in 2008. The European Commission also participates in the work of the IEA. ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT The OECD is a unique forum where the governments of thirty democracies work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. -

Austria: New Withholding Obligation for Employers Without a PE for Wage Tax Purposes

Tax Insights from Global Mobility Austria: New withholding obligation for employers without a PE for wage tax purposes November 11, 2019 In brief Employers of individuals subject to unlimited taxation in Austria will be required to withhold Austrian wage tax as of January 1, 2020. This change in the law stems from the Austrian Tax Amendment Act 2020, which was published in the Federal Law Gazette on October 22, 2019. Previously, the obligation to withhold Austrian income tax via wage tax deduction only applied to employers with a permanent establishment (PE) for wage tax purposes in Austria. In detail New withholding obligation as of 2020 Employers without a PE for wage tax purposes soon will have to withhold tax if they have employees subject to unlimited taxation. An individual is subject to unlimited taxation in Austria if s/he is resident or has his/her habitual abode in Austria. For the obligation to withhold wage tax, it is immaterial whether an employee is tax resident in Austria in accordance with a double taxation convention. In such cases, employers without a wage tax PE also will be subject to further obligations, including liability for wage tax, reporting requirements in relation to the Austrian tax authorities, and an obligation to maintain payroll accounts and submit pay slip documentation. These employer obligations also will apply if a double taxation convention allows pay to be exempted from taxation in Austria. To be released from wage tax obligations in the context of payroll accounting, corresponding documentation