Reappraisal of Thomas Hardy's Earlier Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Desperate Remedies

Colby Quarterly Volume 15 Issue 3 September Article 6 September 1979 Tess of the d'Urbervilles and the "New Edition" of Desperate Remedies Lawrence Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 15, no.3, September 1979, p.194-200 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Jones: Tess of the d'Urbervilles and the "New Edition" of Desperate Reme Tess of the d'Urbervilles and the "New Edition" of Desperate Remedies by LAWRENCE JONES N THE autumn of 1884, Thomas Hardy was approached by the re I cently established publishing firm of Ward and Downey concerning the republication of his first novel, Desperate Remedies. Although it had been published in America by Henry Holt in his Leisure Hour series in 1874, the novel had not appeared in England since the first, anony mous publication by Tinsley Brothers in 1871. That first edition, in three volumes, had consisted of a printing of 500 (only 280 of which had been sold at list price). 1 Since that time Hardy had published eight more novels and had established himself to the extent that Charles Kegan Paul could refer to him in the British Quarterly Review in 1881 as the true "successor of George Eliot," 2 and Havelock Ellis could open a survey article in the Westminster Review in 1883 with the remark that "The high position which the author of Far from the Madding Crowd holds among contemporary English novelists is now generally recognized." 3 As his reputation grew, his earlier novels were republished in England in one-volume editions: Far from the Madding Crowd, A Pair of Blue Eyes, and The Hand ofEthelberta in 1877, Under the Greenwood Tree in 1878, The Return of the Native in 1880, A Laodicean in 1882, and Two on a Tower in 1883. -

Thomas Hardy

Published on Great Writers Inspire (http://writersinspire.org) Home > Thomas Hardy Thomas Hardy Thomas Hardy (1840-1928), novelist and poet, was born on 2 June 1840, in Higher Bockhampton, Dorset. The eldest child of Thomas Hardy and Jemima Hand, Hardy had three younger siblings: Mary, Henry, and Katharine. Hardy learned to read at a very young age, and developed a fascination with the services he regular attended at Stinsford church. He also grew to love the music that accompanied church ritual. His father had once been a member of the Stinsford church musicians - the group Hardy later memorialised in Under the Greenwood Tree - and taught him to play the violin, with the pair occasionally performing together at local dance parties. Whilst attending the church services, Hardy developed a fascination for a skull which formed part of the Grey family monument. He memorised the accompanying inscription (containing the name 'Angel', which he would later use in his novel Tess of the d'Urbervilles [1]) so intently that he was still able to recite it well into old age. [2] Thomas Hardy By Bain News Service [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Adulthood Between the years of 1856-1862, Hardy worked as a trainee architect. He formed an important friendship with Horace Moule. Moule - eight years Hardy's senior and a Cambridge graduate - became Hardy's intellectual mentor. Horace Moule appears to have suffered from depression, and he committed suicide in 1873. Several of Hardy's poems are dedicated to him, and it is thought some of the characters in Hardy's fiction were likely to have been modeled on Moule. -

Pessimism in the Novels of Thomas Hardy Submitted To

PESSIMISM IN THE NOVELS OF THOMAS HARDY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY LOTTIE GREENE REID DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 195t \J p PREFACE "Of all approbrious names,11 saya Florence Emily Hardy, "Hardy resented most 'pessimist.1Hl Yet a thorough atudy of his novels will certainly convince one that his attitude to ward life is definitely pessimistic* Mrs. Hardy quotes him as saying: "My motto is, first correctly diagnose the complaint — in this caae human Ills —- and ascertain the causes then set about finding a remedy if one exists.1'2 According to Hardy, humanity is ill. In diagnosing the case, he is not much concerned with the surface of things, but is more interested in probing far below the surface to find the force behind them. Since this force in his novels is always Fate, and since he is always certain to make things end tragi cally, the writer of this study will attempt to show that he well deserves the name, "pessimist." In this study the writer will attempt to analyze Hardy1 s novels in order to ascertain the nature of his pessimism, as well as point out the techniques by which pessimism is evinced in his novels. In discussing the causes of pessimism, the writer ^■Florence E. Hardy, "The Later Years of Thomas Hardy," reviewed by Wilbur Cross, The Yale Review, XX (September, 1930), p. 176. ' 2Ibid. ii ill deems it necessary to consider Hardy's personality, influences, and philosophy, which appear to be the chief causes of the pes simistic attitude taken by him. -

Wessex Tales

COMPLETE CLASSICS UNABRIDGED Thomas Hardy Wessex Tales Read by Neville Jason 1 Preface 4:04 2 An Imaginative Woman 7:51 3 The Marchmill family accordingly took possession of the house… 7:06 4 She thoughtfully rose from her chair… 6:37 5 One day the children had been playing hide-and-seek… 7:27 6 Just then a telegram was brought up. 5:31 7 While she was dreaming the minutes away thus… 6:10 8 On Saturday morning the remaining members… 5:30 9 It was about five in the afternoon when she heard a ring… 4:36 10 The painter had been gone only a day or two… 4:39 11 She wrote to the landlady at Solentsea… 6:26 12 The months passed… 5:12 13 The Three Strangers 7:58 14 The fiddler was a boy of those parts… 5:57 15 At last the notes of the serpent ceased… 6:19 16 Meanwhile the general body of guests had been taking… 5:13 17 Now the old mead of those days… 5:21 18 No observation being offered by anybody… 6:13 19 All this time the third stranger had been standing… 5:31 20 Thus aroused, the men prepared to give chase. 8:01 21 It was eleven o’clock by the time they arrived. 7:57 2 22 The Withered Arm Chapter 1: A Lorn Milkmaid 5:22 23 Chapter 2: The Young Wife 8:55 24 Chapter 3: A Vision 6:13 25 At these proofs of a kindly feeling towards her… 3:52 26 Chapter 4: A Suggestion 4:34 27 She mused on the matter the greater part of the night… 4:42 28 Chapter 5: Conjuror Trendle 6:53 29 Chapter 6: A Second Attempt 6:47 30 Chapter 7: A Ride 7:27 31 And then the pretty palpitating Gertrude Lodge… 5:02 32 Chapter 8: A Waterside Hermit 7:30 33 Chapter 9: A Rencounter 8:06 34 Fellow Townsmen Chapter 1 5:26 35 Talking thus they drove into the town. -

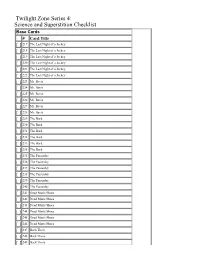

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 217 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 218 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 219 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 220 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 221 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 222 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 223 Mr. Bevis [ ] 224 Mr. Bevis [ ] 225 Mr. Bevis [ ] 226 Mr. Bevis [ ] 227 Mr. Bevis [ ] 228 Mr. Bevis [ ] 229 The Bard [ ] 230 The Bard [ ] 231 The Bard [ ] 232 The Bard [ ] 233 The Bard [ ] 234 The Bard [ ] 235 The Passersby [ ] 236 The Passersby [ ] 237 The Passersby [ ] 238 The Passersby [ ] 239 The Passersby [ ] 240 The Passersby [ ] 241 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 242 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 243 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 244 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 245 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 246 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 247 Back There [ ] 248 Back There [ ] 249 Back There [ ] 250 Back There [ ] 251 Back There [ ] 252 Back There [ ] 253 The Purple Testament [ ] 254 The Purple Testament [ ] 255 The Purple Testament [ ] 256 The Purple Testament [ ] 257 The Purple Testament [ ] 258 The Purple Testament [ ] 259 A Piano in the House [ ] 260 A Piano in the House [ ] 261 A Piano in the House [ ] 262 A Piano in the House [ ] 263 A Piano in the House [ ] 264 A Piano in the House [ ] 265 Night Call [ ] 266 Night Call [ ] 267 Night Call [ ] 268 Night Call [ ] 269 Night Call [ ] 270 Night Call [ ] 271 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 272 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 273 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 274 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 275 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 276 A Hundred -

A Commentary on the Poems of THOMAS HARDY

A Commentary on the Poems of THOMAS HARDY By the same author THE MAYOR OF CASTERBRIDGE (Macmillan Critical Commentaries) A HARDY COMPANION ONE RARE FAIR WOMAN Thomas Hardy's Letters to Florence Henniker, 1893-1922 (edited, with Evelyn Hardy) A JANE AUSTEN COMPANION A BRONTE COMPANION THOMAS HARDY AND THE MODERN WORLD (edited,for the Thomas Hardy Society) A Commentary on the Poems of THOMAS HARDY F. B. Pinion ISBN 978-1-349-02511-4 ISBN 978-1-349-02509-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-02509-1 © F. B. Pinion 1976 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 15t edition 1976 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission First published 1976 by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London and Basingstoke Associated companies in New York Dublin Melbourne Johannesburg and Madras SBN 333 17918 8 This book is sold subject to the standard conditions of the Net Book Agreement Quid quod idem in poesi quoque eo evaslt ut hoc solo scribendi genere ..• immortalem famam assequi possit? From A. D. Godley's public oration at Oxford in I920 when the degree of Doctor of Letters was conferred on Thomas Hardy: 'Why now, is not the excellence of his poems such that, by this type of writing alone, he can achieve immortal fame ...? (The Life of Thomas Hardy, 397-8) 'The Temporary the AU' (Hardy's design for the sundial at Max Gate) Contents List of Drawings and Maps IX List of Plates X Preface xi Reference Abbreviations xiv Chronology xvi COMMENTS AND NOTES I Wessex Poems (1898) 3 2 Poems of the Past and the Present (1901) 29 War Poems 30 Poems of Pilgrimage 34 Miscellaneous Poems 38 Imitations, etc. -

A Laodicean Unabridged

Thomas Hardy COMPLETE CLASSICS A LAODICEAN UNABRIDGED Read by Anna Bentinck Subtitled ‘A Story of To-day’, A Laodicean occupies a unique place in the Thomas Hardy canon. Departing from pre-industrial Wessex, Hardy brings his themes of social constraint, fate, chance and miscommunication to the very modern world of the 1880s – complete with falsified telegraphs, fake photographs, and perilous train tracks. The story follows the life of Paula Power, heiress of her late father’s railroad fortune and the new owner of the medieval Castle Stancy. With the castle in need of restoration, Paula employs architect George Somerset, who soon falls in love with her. However, Paula’s dreams of nobility draw her to another suitor, Captain de Stancy, who is aided by his villainous son, William Dare… Anna Bentinck trained at Arts Educational Schools, London (ArtsEd) and has worked extensively for BBC radio. Her animation voices include the series 64 Zoo Lane (CBeebies). Film credits include the Hammer Horror Total running time: 17:06:20 To the Devil… A Daughter. Her many audiobooks range from Shirley by View our catalogue online at n-ab.com/cat Charlotte Brontë, Kennedy’s Brain by Henning Mankell, Beyond Black by Hilary Mantel, Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys and One Day by David Nicholls to The Bible. For Naxos AudioBooks, she has read Five Children and It, The Phoenix and the Carpet and The Amulet by E. Nesbit and Tess of the d’Urbervilles and Desperate Remedies by Thomas Hardy. 1 A Laodicean 9:15 24 Chapter 11 9:28 2 It is an old story.. -

Thomas Hardy Reception and Reputaion in China Chen Zhen Phd, Teacher of School of Foreign Languages, Qinghai University for Nationalities

The International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Invention 5(01): 4327- 4330 2018 DOI: 10.18535/ijsshi/v5i1.13 ICV 2015: 45.28 ISSN: 2349-2031 © 2018, THEIJSSHI Research Article Thomas Hardy Reception and Reputaion in China Chen Zhen PhD, teacher of School of Foreign Languages, Qinghai University for Nationalities. Study field: British and American Literature, English Teaching. Address: School of Foreign Languages, Qinghai University for Nationalities (West Campus) ,No 3, Middle Bayi Road, Xining City,Qinghai Province, China,Postcode: 810007 Thomas Hardy has been one of the best-loved novelists to liked English novelist in India.”4 Hardy also enjoys a high Chinese readers for nearly a century, which is an uncanny reputation in Japan, whose Thomas Hardy Society founded in phenomenon in the circle of literature reception and 1957 published A Thomas Hardy Dictionary in 1984. This circulation in China. It seems that Hardy has some magic statement can be strengthened by the large store of Hardy power to have kept attracting Chinese literature lovers with his works and research books kept in college libraries. keen insight into nature, profound reflection on humanity and Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto is taken for example, where whole-hearted concern about human fate in the vast universe. I did some research in 2005. It has almost all Hardy‟s works Hardy‟s works saturated with nostalgic sentiments for the including his seven volumes of letters edited by Richard Little traditional way of rural life exert unusual resonance in Chinese Purdy and Michael Millgate as well as a considerable number readers in terms of receptional aesthetic. -

Counterfactual Plotting in the Victorian Novel

Narrative and Its Non- Events: Counterfactual Plotting in the Victorian Novel The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Glatt, Carra. 2016. Narrative and Its Non-Events: Counterfactual Plotting in the Victorian Novel. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493430 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Narrative and its Non-Events: Counterfactual Plotting in the Victorian Novel A dissertation presented by Carra Glatt to The Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of English Harvard University Cambridge Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 Carra Glatt All rights reserved Dissertation Advisor: Elaine Scarry Carra Glatt Narrative and its Non-Events: Counterfactual Plotting in the Victorian Novel Abstract This dissertation examines the role of several types of counterfactual plots in both defining and challenging the borders of nineteenth-century realist fiction. Using texts by Dickens, James, Gaskell and Hardy, I argue for the narrative significance of “active” plot possibilities that, while finally jettisoned by the ascendancy of a triumphant rival, exert an -

Thomas Hardy, Mona Caird and John

‘FALLING OVER THE SAME PRECIPICE’: it was first published in serial form in Tinsley’s Magazine , The Wing of 5 THOMAS HARDY, MONA CAIRD AND Azrael has only recently been reprinted. The Wing of Azrael deserves to be read in its own right, but it is also JOHN STUART MILL rewarding to read it alongside A Pair of Blue Eyes . Such a comparative reading reveals not only how Caird’s novel is in dialogue with Hardy’s, but also the differences and correspondences in the ways each novelist DEMELZA HOOKWAY engages with the philosophy of John Stuart Mill. This essay will consider how Hardy and Caird evoke, explore and re-work, through their cliff- edge narratives, Millian ideas about how individuals can challenge On July 3 1889, Hardy, by his own arrangement, sat next to Mona Caird customs: the qualities they must have, the strategies they must deploy, at the dinner for the Incorporated Society of Authors. 1 Perhaps one of and the difficulties they must negotiate, in order to carry out experiments their topics of conversation was the reaction to Caird’s recently published in living. Like Hardy, Caird regarded Mill as her intellectual hero. When novel The Wing of Azrael . Like Hardy’s A Pair of Blue Eyes in 1873, The asked by the Women’s Penny Paper in 1890 if she was influenced by any Wing of Azrael features a literal cliffhanger which is a formative event women in forming her views on gender equality she replied ‘“No, not in the life of its heroine. This similarity suggests that Caird, a journalist particularly. -

Proquest Dissertations

Seeing Hardy: The critical and cinematic construction of Thomas Hardy and his novels Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Niemeyer, Paul Joseph Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 02:38:24 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/284226 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfiim master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter lace, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon ttw quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, cotored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print t>leedthrough, substandard margins, arxJ improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author dkJ not serKj UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a mte will indicate the deletkxi. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawir>gs, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuir)g from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9' black and white photographic prints are availat>le for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. -

Visual Techniques in Hardy's Desperate Remedies

Visual Techniques in Hardy's Desperate Remedies NORMAN PAGE OST of Hardy's critics pass rapidly over his earliest surviving novel, conscious of the more rewarding ter• M ritories which lie ahead and generally content to dismiss Desperate Remedies (1871) as crude apprentice work — a blind alley of a book which represents a false start, and necessitated a return to the fictional high road be• fore he could find his true direction. An important dissent• er from this view is Professor Guerard, who regards it as "a better novel than is commonly assumed"; but more char• acteristic is the recent comment that "Nothing of impor• tance in the book . anticipates the later novels."1 Without denying its limitations and weaknesses in plotting, charac• terization and style, it seems worth pointing out that sev• eral devices which are utilized extensively in the later novels are to be found in an already well-developed state in this early attempt. Evidently Hardy was quick to grasp the usefulness of certain indirect ways of drawing attention to significant moments in the action of a story. Since he had a strong natural tendency to conceive episodes and situ• ations in visual terms, these devices to some extent fulfil a descriptive purpose; it is equally reasonable, however, to regard them as narrative motifs since their primary func• tion appears to be related to the need to give special em• phasis to crucial phases in the action. Some examples will make their nature and effect clearer. In the opening chapter, the heroine, Cytherea Graye, sits in Hocbridge Town Hall, looking through a window which provides a view of "the upper part of a neighbour- 66 NORMAN PAGE ing church spire": high up on the scaffolding can be seen her father, who is an architect, and four workmen.