Partial Award

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Download/Documents/AFR2537302021ENGLISH.PDF

“I DON’T KNOW IF THEY REALIZED I WAS A PERSON” RAPE AND OTHER SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN THE CONFLICT IN TIGRAY, ETHIOPIA Amnesty International is a movement of 10 million people which mobilizes the humanity in everyone and campaigns for change so we can all enjoy our human rights. Our vision is of a world where those in power keep their promises, respect international law and are held to account. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and individual donations. We believe that acting in solidarity and compassion with people everywhere can change our societies for the better. © Amnesty International 2021 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: © Amnesty International (Illustrator: Nala Haileselassie) (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2021 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 25/4569/2021 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 9 4. SEXUAL VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN AND GIRLS IN TIGRAY 12 GANG RAPE, INCLUDING OF PREGNANT WOMEN 12 SEXUAL SLAVERY 14 SADISTIC BRUTALITY ACCOMPANYING RAPE 16 BEATINGS, INSULTS, THREATS, HUMILIATION 17 WOMEN SEXUALLY ASSAULTED WHILE TRYING TO FLEE THE COUNTRY 18 5. -

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

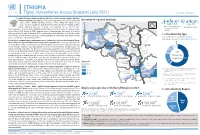

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

Historical Volcanism and the State of Stress in the East African Rift System

Wadge, G. , Biggs, J., Lloyd, R., & Kendall, J. M. (2016). Historical volcanism and the state of stress in the East African Rift System. Frontiers in Earth Science, 4, [86]. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2016.00086 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY Link to published version (if available): 10.3389/feart.2016.00086 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via Frontiers Media at http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/feart.2016.00086/full. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 30 September 2016 doi: 10.3389/feart.2016.00086 Historical Volcanism and the State of Stress in the East African Rift System G. Wadge 1*, J. Biggs 2, R. Lloyd 2 and J.-M. Kendall 2 1 Centre for Observation and Modelling of Earthquakes, Volcanoes and Tectonics (COMET), Department of Meteorology, University of Reading, Reading, UK, 2 Centre for Observation and Modelling of Earthquakes, Volcanoes and Tectonics (COMET), School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK Crustal extension at the East African Rift System (EARS) should, as a tectonic ideal, involve a stress field in which the direction of minimum horizontal stress is perpendicular to the rift. -

Historical Volcanism and the State of Stress in the East African Rift System

Historical volcanism and the state of stress in the East African Rift System Article Accepted Version Open Access Wadge, G., Biggs, J., Lloyd, R. and Kendall, J.-M. (2016) Historical volcanism and the state of stress in the East African Rift System. Frontiers in Earth Science, 4. 86. ISSN 2296- 6463 doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2016.00086 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/66786/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/feart.2016.00086 Publisher: Frontiers media All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online 1 Historical volcanism and the state of stress in the East African 2 Rift System 3 4 5 G. Wadge1*, J. Biggs2, R. Lloyd2, J-M. Kendall2 6 7 8 1.COMET, Department of Meteorology, University of Reading, Reading, UK 9 2.COMET, School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK 10 11 * [email protected] 12 13 14 Keywords: crustal stress, historical eruptions, East African Rift, oblique motion, 15 eruption dynamics 16 17 18 19 20 21 Abstract 22 23 Crustal extension at the East African Rift System (EARS) should, as a tectonic ideal, 24 involve a stress field in which the direction of minimum horizontal stress is 25 perpendicular to the rift. -

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010 R Legend Eritrea E Tigray R egion !ª D 450 ho uses burned do wn d ue to th e re ce nt International Boundary !ª !ª Ahferom Sudan Tahtay Erob fire incid ent in Keft a hum era woreda. I nhabitan ts Laelay Ahferom !ª Regional Boundary > Mereb Leke " !ª S are repo rted to be lef t out o f sh elter; UNI CEF !ª Adiyabo Adiyabo Gulomekeda W W W 7 Dalul E !Ò Laelay togethe r w ith the regiona l g ove rnm ent is Zonal Boundary North Western A Kafta Humera Maychew Eastern !ª sup portin g the victim s with provision o f wate r Measle Cas es Woreda Boundary Central and oth er imm ediate n eeds Measles co ntinues to b e re ported > Western Berahle with new four cases in Arada Zone 2 Lakes WBN BN Tsel emt !A !ª A! Sub-city,Ad dis Ababa ; and one Addi Arekay> W b Afa r Region N b Afdera Military Operation BeyedaB Ab Ala ! case in Ahfe rom woreda, Tig ray > > bb The re a re d isplaced pe ople from fo ur A Debark > > b o N W b B N Abergele Erebtoi B N W Southern keb eles of Mille and also five kebeles B N Janam ora Moegale Bidu Dabat Wag HiomraW B of Da llol woreda s (400 0 persons) a ff ected Hot Spot Areas AWD C ases N N N > N > B B W Sahl a B W > B N W Raya A zebo due to flo oding from Awash rive r an d ru n Since t he beg in nin g of th e year, Wegera B N No Data/No Humanitarian Concern > Ziquala Sekota B a total of 967 cases of AWD w ith East bb BN > Teru > off fro m Tigray highlands, respective ly. -

Starving Tigray

Starving Tigray How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine Foreword by Helen Clark April 6, 2021 ABOUT The World Peace Foundation, an operating foundation affiliated solely with the Fletcher School at Tufts University, aims to provide intellectual leadership on issues of peace, justice and security. We believe that innovative research and teaching are critical to the challenges of making peace around the world, and should go hand-in- hand with advocacy and practical engagement with the toughest issues. To respond to organized violence today, we not only need new instruments and tools—we need a new vision of peace. Our challenge is to reinvent peace. This report has benefited from the research, analysis and review of a number of individuals, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. For that reason, we are attributing authorship solely to the World Peace Foundation. World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School Tufts University 169 Holland Street, Suite 209 Somerville, MA 02144 ph: (617) 627-2255 worldpeacefoundation.org © 2021 by the World Peace Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover photo: A Tigrayan child at the refugee registration center near Kassala, Sudan Starving Tigray | I FOREWORD The calamitous humanitarian dimensions of the conflict in Tigray are becoming painfully clear. The international community must respond quickly and effectively now to save many hundreds of thou- sands of lives. The human tragedy which has unfolded in Tigray is a man-made disaster. Reports of mass atrocities there are heart breaking, as are those of starvation crimes. -

Modelling the Current Fractional Cover of an Invasive Alien Plant and Drivers of Its Invasion in a Dryland Ecosystem

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Modelling the current fractional cover of an invasive alien plant and drivers of its invasion in a dryland Received: 23 July 2018 Accepted: 23 November 2018 ecosystem Published: xx xx xxxx Hailu Shiferaw1,3, Urs Schafner 2, Woldeamlak Bewket3, Tena Alamirew1, Gete Zeleke1, Demel Teketay4 & Sandra Eckert5 The development of spatially diferentiated management strategies against invasive alien plant species requires a detailed understanding of their current distribution and of the level of invasion across the invaded range. The objectives of this study were to estimate the current fractional cover gradient of invasive trees of the genus Prosopis in the Afar Region, Ethiopia, and to identify drivers of its invasion. We used seventeen explanatory variables describing Landsat 8 image refectance, topography, climate and landscape structures to model the current cover of Prosopis across the invaded range using the random forest (RF) algorithm. Validation of the RF algorithm confrmed high model performance with an accuracy of 92% and a Kappa-coefcient of 0.8. We found that, within 35 years after its introduction, Prosopis has invaded approximately 1.17 million ha at diferent cover levels in the Afar Region (12.3% of the surface). Normalized diference vegetation index (NDVI) and elevation showed the highest explanatory power among the 17 variables, in terms of both the invader’s overall distribution as well as areas with high cover. Villages and linear landscape structures (rivers and roads) were found to be more important drivers of future Prosopis invasion than environmental variables, such as climate and topography, suggesting that Prosopis is likely to continue spreading and increasing in abundance in the case study area if left uncontrolled. -

Risk Factors and Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Human Rabies Exposure in Northwestern Tigray, Ethiopia

Gebru G, et al. Risk Factors and Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Human Rabies Exposure in Northwestern Tigray, Ethiopia. Annals of Global Health. 2019; 85(1): 119, 1–12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2518 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Risk Factors and Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Human Rabies Exposure in Northwestern Tigray, Ethiopia Gebreyohans Gebru*, Gebremedhin Romha†, Abrha Asefa‡, Haftom Hadush§ and Muluberhan Biedemariam‖ Background: Rabies is a neglected tropical disease, which is economically important with great public health concerns in developing countries including Ethiopia. Epidemiological information can play an important role in the control and prevention of rabies, though little is known about the status of the disease in many settings of Ethiopia. The present study aimed to investigate the risk factors and spatio-temporal patterns of human rabies exposure in Northwestern Tigray, Ethiopia. Methods: A prospective study was conducted from 01 January 2016 to 31 December 2016 (lapsed for one year) at Suhul general hospital, Northern Ethiopia. Data of human rabies exposure cases were collected using a pretested questionnaire that was prepared for individuals dog bite victims. Moreover, GPS coordinate of each exposure site was collected for spatio-temporal analysis using hand-held Garmin 64 GPS apparatus. Later, cluster of human rabies exposures were identified using Getis-Ord *Gi statistics. Results: In total, 368 human rabies exposure cases were collected during the study year. Age group of 5 to 14 years old were highly exposed (43.2%; 95% CI, 38.2–48.3). Greater number of human rabies exposures was registered in males (63%; 95% CI, 58.0–67.8) than females (37%; 95% CI, 32.1–42.0). -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. T 7402-ET TECHNICAL ANNEX FOR A CREDIT OF SDR 180.2 MILLION Public Disclosure Authorized (USD 230.0 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA FOR AN EMERGENCY RECOVERY PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized November 9, 2000 Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENT (exchange rate effective as of November 9, 2000) Currency Unit = Ethiopian Birr US$1 8.25 GOVERNMENTFISCAL YEAR July 8 - July 7 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS CAS Country Assistance Strategy CSWs Commercial Sex Workers DPPB Disaster Prevention and Preparedness Bureau DPPC Disaster Prevention and Preparedness Commission EDP Ethiopian De-mining Project EEPCo Ethiopian Electric Power Cooperation EMSAP Ethiopia Multi-Sectoral HIV/AIDS Project ERA Ethiopian Roads Authority ERP Emergency Recovery Project/Program ERPMU Emergency Recovery Program Management Unit ESRDF Ethiopia Social Rehabilitation and Development Fund FMU Financial Management Unit H-IMA Humanitarian Mine Action ICB International Competitive Bidding ICR Implementation CompletionReport IDA International Development Association IDPs Internally Displaced Peoples ILO International Labour Organization Kebele The kebele is the lowest administrativeauthority in the regional government hierarchy in Ethiopia MEDaC Ministry of Economic Development and Cooperation NCB National Competitive Bidding NGO Non-governmentalOrganization OAU Organization of African Unity PIP Project ImplementationPlan QCBS Quality and Cost Based Selection RSDP -

Examining Alternative Livelihoods for Improved Resilience and Transformation in Afar

EXAMINING ALTERNATIVE LIVELIHOODS FOR IMPROVED RESILIENCE AND TRANSFORMATION IN AFAR May 2019 Report photos: Dr. Daniel Temesgen EXAMINING ALTERNATIVE LIVELIHOODS FOR IMPROVED RESILIENCE AND TRANSFORMATION IN AFAR May 2019 This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Report authors: Daniel Temesga, Amdissa Teshome, Berhanu Admassu Suggested citation: FAO and Tufts University. (2019). Examining Alternative Livelihoods for Improved Resilience and Transformation in Afar. FAO: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Implemented by: Feinstein International Center Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy Tufts University Africa Regional Office www.fic.tufts.edu © FAO TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... 6 I. BACKGROUND............................................................................................................................................ 8 The Afar Region: context and livelihoods ................................................................................................... 8 The purpose of the study ............................................................................................................................ 8 The study’s approaches and methods ......................................................................................................... -

Semera - Galafi 230 Kv Transmission Line Project

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ethiopian Electric Power Semera - Galafi 230 kV Transmission Line Project ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) FINAL REPORT February 2021 Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia ▪ Ethiopian Electric Power Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Semera - Galafi 230 kV Transmission Line Project Final Report Second Ethiopia-Djibouti Power System Interconnection Project Table of Contents 0 Executive Summary 1 0.1 Introduction and Background 1 0.2 Purpose of the ESIA Study 1 0.3 Project Location 1 0.4 Project Description 2 0.5 Policy and Legal Framework 3 0.6 Methods of Assessment 3 0.7 Description of the Baseline Environment 3 0.8 Project Alternatives 5 0.9 Potential Socio-Environmental Impacts and Mitigation Measures 5 0.10 Stakeholder Consultation 10 0.11 Environmental Management, Monitoring and Evaluation 11 0.12 Institutional Framework for Implementation of the ESIA 11 0.13 Capacity of EEP’s Environment and Social Affairs Office 12 0.14 Environmental Mitigation and Management Costs 12 0.15 Conclusions and Recommendations 12 1 Introduction 13 1.1 Background of the Study 13 1.2 Purpose of the ESIA Study 14 1.3 Objectives of the Study 14 1.4 Approach and Methodology 14 1.5 Scope and Limitations of the study 17 1.5.1 Scope 17 1.5.2 Limitations 17 1.6 Report Structure 18 2 Project Description 19 2.1 Background 19 2.2 Project Justification 19 2.3 Project Location 20 2.4 Salient Features of the Project 21 2.4.1 Transmission Line Route Description 21 2.4.2 Transmission Tower 22 2.4.3 Right