H-France Review Volume 15 (2015) Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16 Exhibition on Screen

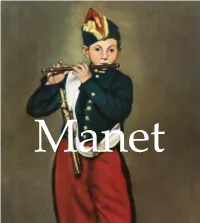

Exhibition on Screen - The Impressionists – And the Man Who Made Them 2015, Run Time 97 minutes An eagerly anticipated exhibition travelling from the Musee d'Orsay Paris to the National Gallery London and on to the Philadelphia Museum of Art is the focus of the most comprehensive film ever made about the Impressionists. The exhibition brings together Impressionist art accumulated by Paul Durand-Ruel, the 19th century Parisian art collector. Degas, Manet, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, and Sisley, are among the artists that he helped to establish through his galleries in London, New York and Paris. The exhibition, bringing together Durand-Ruel's treasures, is the focus of the film, which also interweaves the story of Impressionism and a look at highlights from Impressionist collections in several prominent American galleries. Paintings: Rosa Bonheur: Ploughing in Nevers, 1849 Constant Troyon: Oxen Ploughing, Morning Effect, 1855 Théodore Rousseau: An Avenue in the Forest of L’Isle-Adam, 1849 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Gleaners, 1857 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Angelus, c. 1857-1859 (Barbizon School) Charles-François Daubigny: The Grape Harvest in Burgundy, 1863 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: Spring, 1868-1873 (Barbizon School) Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot: Ruins of the Château of Pierrefonds, c. 1830-1835 Théodore Rousseau: View of Mont Blanc, Seen from La Faucille, c. 1863-1867 Eugène Delecroix: Interior of a Dominican Convent in Madrid, 1831 Édouard Manet: Olympia, 1863 Pierre Auguste Renoir: The Swing, 1876 16 Alfred Sisley: Gateway to Argenteuil, 1872 Édouard Manet: Luncheon on the Grass, 1863 Edgar Degas: Ballet Rehearsal on Stage, 1874 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Ball at the Moulin de la Galette, 1876 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Portrait of Mademoiselle Legrand, 1875 Alexandre Cabanel: The Birth of Venus, 1863 Édouard Manet: The Fife Player, 1866 Édouard Manet: The Tragic Actor (Rouvière as Hamlet), 1866 Henri Fantin-Latour: A Studio in the Batingnolles, 1870 Claude Monet: The Thames below Westminster, c. -

Claude Monet (1840-1926)

Caroline Mc Corriston Claude Monet (1840-1926) ● Monet was the leading figure of the impressionist group. ● As a teenager in Normandy he was brought to paint outdoors by the talented painter Eugéne Boudin. Boudin taught him how to use oil paints. ● Monet was constantly in financial difficulty. His paintings were rejected by the Salon and critics attacked his work. ● Monet went to Paris in 1859. He befriended the artists Cézanne and Pissarro at the Academie Suisse. (an open studio were models were supplied to draw from and artists paid a small fee).He also met Courbet and Manet who both encouraged him. ● He studied briefly in the teaching studio of the academic history painter Charles Gleyre. Here he met Renoir and Sisley and painted with them near Barbizon. ● Every evening after leaving their studies, the students went to the Cafe Guerbois, where they met other young artists like Cezanne and Degas and engaged in lively discussions on art. ● Monet liked Japanese woodblock prints and was influenced by their strong colours. He built a Japanese bridge at his home in Giverny. Monet and Impressionism ● In the late 1860s Monet and Renoir painted together along the Seine at Argenteuil and established what became known as the Impressionist style. ● Monet valued spontaneity in painting and rejected the academic Salon painters’ strict formulae for shading, geometrically balanced compositions and linear perspective. ● Monet remained true to the impressionist style but went beyond its focus on plein air painting and in the 1890s began to finish most of his work in the studio. Personal Style and Technique ● Use of pure primary colours (straight from the tube) where possible ● Avoidance of black ● Addition of unexpected touches of primary colours to shadows ● Capturing the effect of sunlight ● Loose brushstrokes Subject Matter ● Monet painted simple outdoor scenes in the city, along the coast, on the banks of the Seine and in the countryside. -

Dillonsd2014.Pdf (377.0Kb)

UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL OKLAHOMA DR. JOE C. JACKSON COLLEGE OF GRADUATE STUDIES Edmond, Oklahoma Hemingway: Insights on Military Leadership A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Of MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH By Shawn Dillon Edmond, Oklahoma 2014 Abstract of Thesis University of Central Oklahoma Edmond, Oklahoma NAME: Shawn Dillon TITLE OF THESIS: Hemingway: Insights on Military Leadership DIRECTOR OF THESIS: Dr. G.S. Lewis PAGES: 86 The literature of Ernest Hemingway is rich with military lessons derived from his lifetime of proximity to war and his understanding of soldiers and leaders at all levels as presented through his characters. Hemingway wrote two significant military works that treat deeply the psyche and behavior of soldiers in war: For Whom the Bell Tolls presented a guerilla band led by an American professor named Robert Jordan, and exposed the different types of junior and senior leaders, as well as an ideal soldier in Anselmo, the old, untrained partisan. Across the River and Into the Trees was equally rich in military insights, at a much higher level of command, through the bitter musings of Colonel Cantwell. Hemingway’s fiction represented and reproduced the detailed awareness he had of soldiers and leaders, good and bad. He was born with the natural instinct to lead, and through his proximity to men performing humanity’s most vaunted of tests, he produced a body of fiction that can serve collectively as a manual for understanding soldiers, terrain, and military -

Claude Monet : Seasons and Moments by William C

Claude Monet : seasons and moments By William C. Seitz Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1960 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art in collaboration with the Los Angeles County Museum: Distributed by Doubleday & Co. Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2842 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art The Museum of Modern Art, New York Seasons and Moments 64 pages, 50 illustrations (9 in color) $ 3.50 ''Mliili ^ 1* " CLAUDE MONET: Seasons and Moments LIBRARY by William C. Seitz Museumof MotfwnArt ARCHIVE Claude Monet was the purest and most characteristic master of Impressionism. The fundamental principle of his art was a new, wholly perceptual observation of the most fleeting aspects of nature — of moving clouds and water, sun and shadow, rain and snow, mist and fog, dawn and sunset. Over a period of almost seventy years, from the late 1850s to his death in 1926, Monet must have pro duced close to 3,000 paintings, the vast majority of which were landscapes, seascapes, and river scenes. As his involvement with nature became more com plete, he turned from general representations of season and light to paint more specific, momentary, and transitory effects of weather and atmosphere. Late in the seventies he began to repeat his subjects at different seasons of the year or moments of the day, and in the nineties this became a regular procedure that resulted in his well-known "series " — Haystacks, Poplars, Cathedrals, Views of the Thames, Water ERRATA Lilies, etc. -

Manet and Modern Beauty

Tyler E. Ostergaard exhibition review of Manet and Modern Beauty Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020) Citation: Tyler E. Ostergaard, exhibition review of “Manet and Modern Beauty ,” Nineteenth- Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2020.19.1.15. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Ostergaard: Manet and Modern Beauty Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020) Manet and Modern Beauty Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago May 26, 2019–September 8, 2019 Getty Center, Los Angeles October 8, 2019–January 12, 2020 Catalogue: Scott Allan, Emily A. Beeny, and Gloria Groom, with Bridget Alsdorf, Carol Armstrong, Helen Burnham, Leah Lehmbeck, Devi Ormond, Catherine Schmidt Patterson, and Samuel Rodary, Manet and Modern Beauty: The Artist’s Last Years. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019. 400 pp.; 206 color and 97 b&w illus., 1 table; bibliography; index. $65 (hardcover) ISBN: 978–1606066041 How are we to classify Manet’s last paintings? This question drives the new exhibition Manet and Modern Beauty, which ran at the Art Institute of Chicago from May 26, 2019 to September 8, 2019, and then at the Getty Center, Los Angeles from October 8, 2019 to January 12, 2020. Organized by curators Scott Allan, Emily A. Beeny, and Gloria Groom, Manet and Modern Beauty focuses on Manet’s production—hardly just paintings—from the mid-1870s until his death on April 30, 1883, at age fifty-one. -

A Guide to Impressionism

A Guide to Impressionism Learn about the history and artistic style of the Impressionists in this teacher’s resource. Find out why the Impressionists were considered so shocking and how they have influenced art over a hundred years later. Explore the art of Monet, Renoir, Degas, and more! Grade Level: Adult, College, Grades 6-8, Grades 9-12 Collection: European Art, Impressionism Culture/Region: Europe Subject Area: Fine Arts, History and Social Science, Visual Arts Activity Type: Art in Depth THE SHOCKING NEW ART MOVEMENT The word “impressionism” makes most people think of beautiful, sunlit paintings of the French countryside; glorious gardens and lily ponds; and fashionable Parisians enjoying life in charming cafes. But in 1874, when the men and women who came to be known as the Impressionists first exhibited their work, their style of painting was considered shocking and outrageous by all but the most forward-thinking viewers. Why did these young artists cause such an uproar? The following comparison shows how their radical ideas, techniques, and subjects broke the time-honored rules and traditions of art in late 19th-century France. “What do we see in the work of these men? Nothing but defiance, almost an insult to the tastes and intelligence of the public.” -Etienne Carjat, “L’exposition du bouldevard des Capucines,” Le Patriote Francais (1874) “There is little doubt that Impressionist landscape paintings are the most…appreciated works of art ever produced.” –Richard Brettell and Scott Schaefer, A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape The accepted style of painting often featured: Great historical subjects or mythological scenes that were meant to be morally uplifting; An emphasis on line, filled in with color; Smooth, almost invisible brushstrokes; Paintings primarily done in the artist’s studio The Judgment of Paris François-Xavier Fabre, 1808 Oil on canvass Adolph D. -

L-G-0000349593-0002314995.Pdf

Manet Page 4: Self-Portrait with a Palette, 1879. Oil on canvas, 83 x 67 cm, Mr et Mrs John L. Loeb collection, New York. Designed by: Baseline Co Ltd 127-129A Nguyen Hue, Floor 3, District 1, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam © Sirrocco, London, UK (English version) © Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyrights on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case we would appreciate notification ISBN 978-1-78042-029-5 2 “He was greater than we thought he was.” — Edgar Degas 3 Biography 1832: Born Edouard Manet 23 January in Paris, France. His father is Director of the Ministry of Justice. Edouard receives a good education. 1844: Enrols into Rollin College where he meets Antonin Proust who will remain his friend throughout his life. 1848: After having refused to follow his family’s wishes of becoming a lawyer, Manet attempts twice, but to no avail, to enrol into Naval School. He boards a training ship in order to travel to Brazil. 1849: Stays in Rio de Janeiro for two years before returning to Paris. 1850: Returns to the School of Fine Arts. He enters the studio of artist Thomas Couture and makes a number of copies of the master works in the Louvre. 1852: His son Léon is born. He does not marry the mother, Suzanne Leenhoff, a piano teacher from Holland, until 1863. -

Manet, Inventeur Du Moderne

André Dombrowski exhibition review of Manet, inventeur du Moderne Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012) Citation: André Dombrowski, exhibition review of “Manet, inventeur du Moderne,” Nineteenth- Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring12/ manet-inventeur-du-moderne. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Dombrowski: Manet, inventeur du Moderne Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012) Manet, inventeur du Moderne Musée d’Orsay, Paris April 5 – July 17, 2011 Catalogue: Manet, inventeur du Moderne/Manet: The Man Who Invented Modernity. Ed. Stéphane Guégan, with contributions by Helen Burnham, Françoise Cachin, Isabelle Cahn, Laurence des Cars, Guy Cogeval, Simon Kelly, Nancy Locke, Louis-Antoine Prat, and Philippe Sollers. Paris: Musée d’Orsay and Gallimard, 2011. 336 pages; 280 illustrations; key dates; list of exhibited works; selected bibliography; index. Available in French and English editions. € 42. ISBN: 978 2 35 433078 1 Once you actually managed to stand in front of most of the Manet paintings gathered at the Orsay this summer, the rewards were endless (fig. 1).[1] In painting after painting, you were reminded what made him one of the nineteenth century’s most gifted and nuanced artists. The bravura with which he applied paint lends his world an elegant ease that emerges less as reality than as fraught dream and wish. The unusually stark contrasts in light and dark color he employed to destroy centuries’ old rules of academic decorum morph into social distinctions as much as aesthetic ones (struggles over visibility and invisibility, identity and non-identity, subjectivity and objectivity, order and disorder, hierarchy and chaos). -

The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945 The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Editor 4525 Oak Street, Kansas City, Missouri 64111 | nelson-atkins.org Edouard Manet | The Croquet Party, 1871 The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art | French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945 Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, 1871 Artist Edouard Manet, French, 1832–1883 Title The Croquet Party Object Date 1871 Alternate and Variant The Croquet Party at Boulogne-sur-Mer; La partie de croquet Titles Medium Oil on canvas Dimensions 18 x 28 3/4 in. (45.7 x 73 cm) (Unframed) Signature Signed lower right: Manet Credit Line The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Marion and Henry Bloch, 2015.13.11 doi: 10.37764/78973.5.522 the croquet lawn outside the casino at Boulogne-sur- Catalogue Entry Mer, in northern France. On the far left is Paul Roudier, the artist’s childhood friend and a central member of Manet’s social circle; he is the only figure in the scene to Citation address the spectator directly.1 Alongside him is Jeanne Gonzalès (1852–1924), a talented young painter who Chicago: would enjoy recognition at the Paris Salon from the late 1870s (Fig. 1).2 Jeanne was the younger sister of the Simon Kelly, “Edouard Manet, The Croquet Party, painter Eva (1849–1883), who was Manet’s favorite 1871,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, female pupil. Jeanne, too, received artistic lessons from ed., French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Manet and frequented his studio.3 She looks toward Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Léon Leenhoff, Manet’s stepson (and, possibly, his Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), biological son) and a favorite model for the artist.4 To the https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.522.5407 right is Léon’s mother—Manet’s wife, Suzanne Leenhoff MLA: —who raises her mallet to hit a croquet ball alongside an unknown partner. -

Impressionism

IMPRESSIONISM Eugène Boudin (1824 – 1898) was one of the first French landscape painters to paint outdoors. Boudin was a marine painter, and expert in the rendering of all that goes upon the sea and along its shores. His pastels, summary and economic, garnered the splendid eulogy of Baudelaire; and Corot called him the "king of the skies.” He opened a small picture framing shop in Le Havre and exhibited artists working in the area, such as Jean-François Millet, and Thomas Couture who encouraged young Boudin to follow an artistic career. Boudin, The Beach at Villerville 1864 In 1857/58 Boudin befriended the young Claude Monet, then only 18, and persuaded him to give up his teenage caricature drawings and to become a landscape painter, instilling in the younger painter a love of bright hues and the play of light on water later evident in Monet's Impressionist paintings. They remained lifelong friends and Boudin joined Monet and his young friends in the first Impressionist exhibition in 1873. Boudin, Sailboats at Trouville 1884 Johan Jongkind (1819 – 1891) was a Dutch painter and printmaker. He painted marine landscapes in a free manner and is regarded as a forerunner of Impressionism, introducing the painting of genre scenes from the tradition of the Dutch Golden Age. From 1846 he moved to Paris, to further his studies. Two years later, he had work accepted for the Paris Salon, receiving acclaim from critic Charles Baudelaire and later on from Émile Zola. Returning to Rotterdam in1865 he moved back to Paris in1861, where he rented a studio Jongkind, in Montparnasse, the following year meeting in View from the Quai d'Orsay 1854 Honfleur Sisley, Boudin and the young Monet. -

Edouard Manet

Edouard Manet Edouard Manet (mah-NAY) 1832-1883 French Painter Edouard Manet was a transitional figure in 19th Vocabulary century French painting. He bridged the classical tradition of Realism and the new style of Impressionism—A style of art that originated in Impressionism in the mid-1800s. He was greatly 19th century France, which concentrated on influenced by Spanish painting, especially changes in light and color. Artists painted Velazquez and Goya. In later years, influences outdoors (en plein air) and used dabs of pure from Japanese art and photography also affected color (no black) to capture their “impression” of his compositions. Manet influenced, and was scenes. influenced by, the Impressionists. Many considered him the leader of this avant-garde Realism—A style of art that shows objects or group of artists, although he never painted a truly scenes accurately and objectively, without Impressionist work and personally rejected the idealization. Realism was also an art movement in label. 19th century France that rebelled against traditional subjects in favor of scenes of modern Manet was a pioneer in depicting modern life by life. generating interest in this new subject matter. He borrowed a lighter palette and freer brushwork Still life—A painting or drawing of inanimate from the Impressionists, especially Berthe Morisot objects. and Claude Monet. However, unlike the Impressionists, he did not abandon the use of black in his painting and he continued to paint in his studio. He refused to show his work in the Art Elements Impressionist exhibitions, instead preferring the traditional Salon. Manet used strong contrasts and Color—Color has three properties: hue, which is bold colors. -

Revisedimp&Postcurrheathcote07

FIRST CLASS - STYLES OF PORTRAITURE I. INTRODUCTION Since the early 1990s, elementary students at the Heathcote School in Scarsdale, New York have been introduced to great masterpieces of art through the Learning to Look program, an art appreciation and art history curriculum that teaches children how to look at art. Kindergartners at the school study “The Elements of Art,” specially-devised lesson plans that teach children to “read” a work of art according to the artist’s use of the Elements of Art—color, line, shape, texture, light/dark, and space. Grades 1 through 5 follow a five-year sequential curriculum plan that broadly covers the development of art history from the mid-eighteenth century to the 1960s in both Europe and America as follows: 2006-2007 Late 18th & 19th century European Painting & Sculpture 2007-2008 Impressionist & Post-Impressionist Art 2008-2009 Modern Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art 2009-2010 Art of the 1950s & 1960s at the Museum of Modern Art 2010-2011 American Art: From Colonial Times to the 1890s This year students at Heathcote School are deepening their knowledge of 19th century European Art by studying one particular art historical period: Impressionist & Post- Impressionist Art. At the beginning of the first class, the teacher should introduce him- or-herself and welcome students to a new year of Learning to Look. Inquire if there are any students who have never had a Learning to Look class before. If so, ask some of their classmates to explain what we do together during the six times of the year that this class meets.