Silicon Valley Origins: the Mission and Pueblo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic House Museums

HISTORIC HOUSE MUSEUMS Alabama • Arlington Antebellum Home & Gardens (Birmingham; www.birminghamal.gov/arlington/index.htm) • Bellingrath Gardens and Home (Theodore; www.bellingrath.org) • Gaineswood (Gaineswood; www.preserveala.org/gaineswood.aspx?sm=g_i) • Oakleigh Historic Complex (Mobile; http://hmps.publishpath.com) • Sturdivant Hall (Selma; https://sturdivanthall.com) Alaska • House of Wickersham House (Fairbanks; http://dnr.alaska.gov/parks/units/wickrshm.htm) • Oscar Anderson House Museum (Anchorage; www.anchorage.net/museums-culture-heritage-centers/oscar-anderson-house-museum) Arizona • Douglas Family House Museum (Jerome; http://azstateparks.com/parks/jero/index.html) • Muheim Heritage House Museum (Bisbee; www.bisbeemuseum.org/bmmuheim.html) • Rosson House Museum (Phoenix; www.rossonhousemuseum.org/visit/the-rosson-house) • Sanguinetti House Museum (Yuma; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/museums/welcome-to-sanguinetti-house-museum-yuma/) • Sharlot Hall Museum (Prescott; www.sharlot.org) • Sosa-Carrillo-Fremont House Museum (Tucson; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/welcome-to-the-arizona-history-museum-tucson) • Taliesin West (Scottsdale; www.franklloydwright.org/about/taliesinwesttours.html) Arkansas • Allen House (Monticello; http://allenhousetours.com) • Clayton House (Fort Smith; www.claytonhouse.org) • Historic Arkansas Museum - Conway House, Hinderliter House, Noland House, and Woodruff House (Little Rock; www.historicarkansas.org) • McCollum-Chidester House (Camden; www.ouachitacountyhistoricalsociety.org) • Miss Laura’s -

Inventory to Negatives and Slides Page 1

Series II: Inventory to Negatives and Slides College of the Pacific Female Institute Building Envelope 329C 100-mile Relay, Burcher's Corners Santa Clara/Sunnyvale Envelope 326 14th St. San Jose 1887 Horsecar Envelope 177 21-Mile House Envelope 330A A. K. Haehnlen Bus. Cd. Envelope 293 A. M. Pico Envelope 334 A. P. Giannini Envelope 282 Abdon Leiva- Member of Vasques Gang- Husband of Woman Seduced By Vasquez Envelope 229 Above Santa Cruz Avenune on Main Envelope 261 Adam's Home Envelope 345 Adams, Sheriff John Envelope 109 Adobe Building in Santa Clara Envelope 329 Adobe Building on Mission Santa Clara (Torn Down) Envelope 322 Adobe House Envelope 241 Adobe House of Fulgencio Higuera Envelope 328 Adobe N. Market - Pacific Junk Store Envelope 150 Adobe Near Alviso Envelope 324 Adobe, Sunol Envelope 150 Advent Church, Spring, 1965 Envelope 329A Adventist Church, 1965 Envelope 329D Aerial Shot Los Gatos, circa 1950s Envelope 261 Aerial View of Quito Park Envelope 301 Agnew Flood, 1952 Envelope 105 Agnew Flood, 1952 Envelope 126 Agnews State Hospital Envelope 351 Ainsley Cannery, Campbell Envelope 338 Ainsley Cannery, Campbell Envelope 286 Air Age Envelope 160 Airships & Moffett Field Envelope 140 Alameda, The Envelope 331 Alameda, The Envelope 109 Alameda, The Envelope 195 Alameda, The - Hill Painting Envelope 163 Alameda, The Early Note Willow Trees Envelope 331 Alameda, The, circa 1860s Envelope 122 Alameda, The, Near Car Barn Note Water Trough Hose Drawn Street Car Tracks Envelope 331 Alexander Forbes' Two Story Adobe Envelope 137 Alice Hare Pictures Envelope 150 All San Jose Police Officers in 1924 (Missing) Envelope 218 Alma Rock Park Commissioners Envelope 246 Almaden - Englishtown Envelope 237 Almaden Mine Drafting Room Envelope 361 Almaden Train Station Envelope 193 Almaden Valley, Robertsville, Canoas Creek Area Envelope 360 Altar of Church (Holy Family?) Envelope 197 Alum Rock -- Peninitia Creek Flood 1911 Envelope 106 Alum Rock at "The Rock" Envelope 107 Alum Rock Canyon Train- A. -

Convention and Cultural District San José State University St James Park

N M o n t g o m e r y S t t Clin tumn C ton Au A B C D E F G H I J d v l v B N S A n Market Center VTA Light Rail t Guadalupe Gardens Mineta San José Japantown African A e t o e u S North c d m e k t a 1 mile to Mountain View 1.1 miles a 0.8 miles International Airport n American u t i o m a D m r l r + Alum Rock n 1 e n e A 3.2 miles Community t r A T Avaya Stadium t S S v N o St James t Services h t N 2.2 miles 5 Peralta Adobe Arts + Entertainment Whole Park 0.2 miles N Foods Fallon House St James Bike Share Anno Domini Gallery H6 Hackworth IMAX F5 San José Improv I3 Market W St John St Little Italy W St John St 366 S 1st St Dome 201 S Market St 62 S 2nd St Alum Rock Alum Food + Drink | Cafés St James California Theatre H6 Institute of H8 San José G4 Mountain View 345 S 1st St Contemporary Art Museum of Art Winchester Bike Share US Post Santa Teresa 560 S 1st St 110 S Market St Oce Camera 3 Cinema I5 One grid square E St John St 288 S 2nd St KALEID Gallery J3 San José Stage Co. H7 Center for the E5 88 S 4th St 490 S 1st St Trinity represents approx. -

Recent Community & Partnership Grants 100 Years Of

COMMUNITY SERVICE INTERNATIONAL SERVICE Recent Community & Partnership Grants FELLOWSHIP ACT for Mental Health, Inc. Counseling management software & two computers Our Endowment grants funds for tangible improvements right here in San Alum Rock Counseling Center Youth mentoring program – ropes course Jose, right now. Because the Endowment’s principal will remain intact forever, American Assoc. University Women Bags for holiday gifts for Gifts for Teens program 100 Years of Service it ensures that San Jose Rotarians will remain responsive to community needs American Cancer Society Walkie-talkies to use in Relay for Life event American Red Cross Five computer workstations in the future. San Jose Rotary continues to grow the $3+ million Endowment Arts Council Silicon Valley Art supplies for ArtsConnect youth education During the past 100 years, Members of the Rotary Club of San Jose have that supports these community programs and the wonderful projects done by Assistance League of San Jose School uniforms SJ Unified/Franklin-McKinley District volunteered over 3 million hours for community and international service and our committees every year. Ballet San Jose Silicon Valley Industrial sewing machines for costume department given over $5 million in grants to 150 community organizations in San Jose. Bill Wilson Center Washer and dryer for teen shelter From installing the first city street lights in 1915 to donating $1,000,000 towards Boys & Girls Clubs of Silicon Valley Science supplies for after school programs a meeting facility for community groups in 2003, San Jose Rotary has been at the Boy Scouts Automatic defibrulators for 2 camps Breathe California of the Bay Area Commercial-quality color laser printer forefront of efforts to build the infrastructure and social fabric of our community. -

CITY of CUPERTINO Cupertino

A MONTHLY PUBLICATION OF THE CITY OF CUPERTINO cupertino volume XXXVIII no.4 | may 2015 IN THIS ISSUE Cupertino Recognizes Community Volunteers April 25 & 26, 2015, 10 am – 5 pm Individuals and groups who have made outstanding contributions to the City of Cupertino will be honored Thursday, May 28. This year, nine individuals and two organizations will receive the Cupertino Recognizes Extra Steps Taken (CREST) Award. – see details on page 2 Bike to Work Day Thursday, May 14, 2015 Join the Cupertino Bicycle Pedestrian Commission and Cupertino Library on Thursday, May 14 for the 21st Annual Bike to Work Day! – see details on page 3 Celebrate Cupertino Day at Blackberry Farm May 3, 2014, 10 am - 6 pm 21979 San Fernando Avenue, Cupertino – see details on page 3 CONTENTS CREST Award Winners . 2 Cupertino Symphonic Band Spring Concert . 10 Bike to Work Day . 3 Eco News . 10 Cupertino Day at Blackberry Farm . 3 Gold is the New Green! . 10 Wild Game Feed . 3 We Want Your Kitchen Scraps! . 11 Cupertino Poet Laureate . 3 Shop Green and Shop Local! . 11 Simply Safe . 4 Clean Our Creeks! . 11 Roots . 5 Community & City Meetings Calendar . 12-13 Cupertino Library . 6-7 Council Actions . 14 Childrens’ Programs . 6-7 The Better Part . 15 Adult, Teen and Family Programs . 6-7 New Businesses . 15 Adult 50 Plus News . 8-9 Adult 50 Plus Programs/Trips . 9 A Monthly Publication of The City of Cupertino happenings in cupertino CREST Award Winners, continued from page 1 Cupertino Recognizes Community Volunteers The awards ceremony and reception that includes a brief presentation by City Councilmem- bers will be held on Thursday, May 28, 7 pm at the Cupertino Community Hall, 10350 Torre Avenue. -

Diridon to Downtown a Community Assessment Report

DIRIDON TO DOWNTOWN A Community Assessment Report DEPARTMENT OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING GRADUATE CAPSTONE STUDIO FALL 2018 & SPRING 2019 Diridon To Downtown A Community Assessment Report CREATED BY SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE CAPSTONE STUDIO CLASS DEPARTMENT OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING FALL 2018 & SPRING 2019 4 5 Contents Executive Summary 12 Chapter One Chapter Three Chapter Five CONNECTING PLACES, CONVENTION CENTER 43 COMMUNITY FINDINGS AND CONNECTIVIY ASSESSMENT CONNECTING COMMUNITIES 19 3.1 History and Development Patterns 45 67 1.1 The Study Area 20 3.2 Community Characteristics 48 5.1 Community Findings 68 1.2 Preparing the Assessment 22 3.3 Mobility Options and Quality of Place 49 5.2 Connectivity Assessment 75 1.3 Objectives 22 3.4 Built Environment and Open Space 51 5.3 Results 81 1.4 Methodology 24 3.5 Short-Term Recommendations 53 1.5 Assessment Layout 25 Chapter Two Chapter Four Chapter Six DIRIDON STATION 27 SAN PEDRO SQUARE 55 RECOMMENDATIONS 83 2.1 History and Development Patterns 29 4.1 History and Development Patterns 57 6.1 Short-Term Recommendations 85 2.2 Community Characteristics 31 4.2 An Old (New) Community 59 6.2 Long-Term Recommendations 102 2.3 Mobility Options and Quality of Place 32 4.3 Mobility Options and Quality of Place 60 6.3 Assessment Limitations 105 2.4 Built Environment and Open Space 36 4.4 Short-Term Recommendations 64 6.4 Next Steps and Ideas for the Future 106 2.5 Short-Term Recommendations 40 6 7 INSTRUCTORS Rick Kos & Jason Su CLASS FALL 2018 SPRING 2019 Juan F. -

Based Organizations

Office of the City Auditor Report to the City Council City of San José AUDIT OF THE CITY’S OVERSIGHT OF FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE TO COMMUNITY- BASED ORGANIZATIONS The City Does Not Have A Central Mechanism To Track All Forms Of Financial Assistance The City Needs To Improve Its Monitoring Of Community-Based Organizations That Operate City Facilities The City’s Process For Leasing Property To Community-Based Organizations Needs Better Coordination And Oversight Further Improvements Are Needed To Ensure Appropriate Oversight Of Grants And All Other Forms Of Financial Assistance Report 08-04 November 2008 Office of the City Auditor Sharon W. Erickson, City Auditor November 12, 2008 Honorable Mayor and Members of the City Council 200 East Santa Clara Street San Jose, CA 95113 Transmitted herewith is the report An Audit of the City’s Oversight of Financial Assistance to Community-Based Organizations. This report is in accordance with City Charter Section 805. An Executive Summary is presented on the blue pages in the front of this report. The City Administration’s response is shown on the yellow pages before Appendix A. This report will be presented at the November 20, 2008 meeting of the Public Safety, Finance & Strategic Support Committee. If you need any additional information, please let me know. The City Auditor’s staff members who participated in the preparation of this report are Steven Hendrickson, Gitanjali Mandrekar, Carolyn Huynh, Lynda Brouchoud, and Jazmin LeBlanc. Respectfully submitted, Sharon W. Erickson City Auditor finaltr SE:bh cc: Peter Jensen Christine Shippey Mignon Gibson Mark DeCastro Katy Allen Deanna Santana Sandra Murillo Barbara Jordan Leslye Krutko Jeff Ruster Jay Castellano Phil Prince Albert Balagso Ed Shikada Steve Ferguson Kara Capaldo Paul Krutko Neil Stone Steve Turner Debra Figone Kerry Adams-Hapner Evet Loewen 200 E. -

Fandango! – Celebrating Life at the Adobe at San Pedro Square Market Sunday, August 24Th – 12 PM to 4 PM

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Friends & Family Series: Fandango! – Celebrating Life at the Adobe at San Pedro Square Market Sunday, August 24th – 12 PM to 4 PM San José, CA – August 4, 2014. On Sunday, August 24 from 12 PM to 4 PM, is the annual Fandango! at the Peralta Adobe Historic Site, in the heart of the San Pedro Square Market. This date commemorates the death of Luis Maria Peralta 162 years ago. Peralta was one of the first Alcalde, or Mayors, of the Pueblo de San Jose de Guadalupe. A Californio, he lived in the Adobe with his family. “Fandango is a fun way to celebrate the heritage of what we know today as Silicon Valley,” said Alida Bray, President and CEO of History San José. “So much of our language, foods, and aspects of our daily lives have been influenced by Spanish and Mexican culture. Come see how it all started!” Come and explore the history of the Valley’s first inhabitants, the Ohlone people. Use a mataté to crush acorns, the main food source of the Ohlone’s, learn how the early Spanish settlers used adobe “mud” for building materials and make an Adobe Brick, and be a gaucho and practice your roping skills. Make a corn husk doll, create your own cattle brand, and hand dip a candle. Enjoy music from Los Arribeños while feasting on the many foods available from the San Pedro Market. Activity tickets are one dollar each or six for $5. History San José members earn six free tickets when presenting membership card. -

San Jose's History

San Jose’s History San Jose’s Original Inhabitants Long before Spaniards arrived in California, thousands of Native Americans inhabited the coastal lands from San Francisco down to Big Sur. Their descendants now call themselves Ohlone, and San Jose’s Alum Rock Park was once home to one of the Ohlone hunter-gatherer tribes, who were the first of many to shape the history of San Jose. On the Trail of Juan Bautista de Anza When the Spaniards arrived, they built a chain of 21 missions from San Diego up to Sonoma, and a series of forts. In 1776, Captain Juan Bautista de Anza was charged by the Spanish king to lead settlers from New Spain to California. After stop- ping at Monterey, de Anza continued north, scouting sites for the Presidio of San Francisco, Mission San Francisco de Asis, and El Pueblo de San Jose de Guadalupe, now San Jose. El Pueblo de San Jose de Guadalupe was officially founded on November 29, 1777, the first town in the Spanish colony Nueva California. It took its name from Saint Joseph, patron saint of pioneers and travelers, and from the Guadalupe River. You can visit the last surviving adobe from the de Anza era—the 1797 Peralta Adobe at San Pedro Square Market in downtown San Jose. Castillero and New Almaden – California’s First Major Mining Operation Before the Gold Rush, the hills around San Jose sounded with the din of mining work. The Ohlone long appreciated the red ore, cinnabar and introduced their source to Mexican military captain and mining engineer, Andres Castillero. -

Research Files

McKay Research Files - Folder Listing: Agnews Airport & Jim Nissen Airport Airport noise & airport expansion San Jose airport: talk at Rotary The Alameda and Hester Park The Alameda: Living History Day, 1998-10-04 Alexian brothers: hospital rename Alma Alum Rock carousel Alum Rock mineral springs Alum Rock park & railroad Adkins, Walt: Chief of Police Alviso's: Vahl, Amelia American Revolution - men of/disasters Antique printing equipment: Lindner Press Architects - San Jose & Santa Clara County Kort Arada family/ Haenlen Orange Mill Clyde Arbuckle memorial - 2000-01-10 Clyde Arbuckle commemoration - grant form Clyde and Helen Arbuckle Clyde Arbuckle's History of San Jose Jim Arbuckle (Redding) San Jose sewage disposal plant - Alviso San Joseans - Joseph Aram 1906 aerial photo of San Jose - by George Lawrence Notes on Pioneer talk - San Jose artists - 1998-07-03 Bossack - art restorer, Capitola Argonauts - Donner Trail Audio/video TV tapes - Local history Austin Corners - Los Gatos, Saratoga Rd. Award nominations Backesto Park People of San Jose - John Ball Richard Barrett Bancroft Library, Berkeley - Peralta and early Pueblo Bascom Monument - Oak Hill - dedicated 2000-09-09 - donations, etc. Grandma Bascom's Story, 1887 - interview in Overland Monthly, 1887 Grandma Bascom - script Battle of Santa Clara - speech to campers - 1978-10-14 Jack Bean book - sticker info Bear Flag Republic Bees, Honey - introduced to California - Clyde Arbuckle story Begonias - Antonelli Brothers Bellarmine - history, 1922-1934 Benech (?) - El Pirul migrant -

Dig Into the Past at History San José's Archaeology Days at Peralta Adobe

MEDIA ALERT and PHOTO OP: Dig Into the Past at History San José’s Archaeology Days at Peralta Adobe at San Pedro Square Market San José, CA – December 18, 2012 On Sunday, January 27 and again on February 24, from 11 AM to 3 PM ‐‐‐ Archaeology Day at the Peralta Adobe at San Pedro Square Market will offer children an opportunity to be junior archaeologists. Stanford Archaeology Center students will be at the Peralta Adobe historic site conducting a mock excavation, screening, artifact identification and artifact reconstruction. “It’s exciting for us to be able to share our research on San Jose’s past with today’s current residents,” said Barbara Voss, Associate Professor of Anthropology at Stanford University. “We’re looking forward to meeting the next generation of young archaeologists.” This free family educational program will allow individuals to collect stickers for each activity to place in Archaeology Passports and become ‘certified’ as a Junior Archaeologist. The oldest home in San Jose, the Peralta Adobe, serves as a perfect archaeological location. It is the centerpiece for San Pedro Square Market at 175 West Saint John Street in downtown San Jose. It is just across the street from the Fallon House, a mid‐19th century Victorian home. The public archaeology activities are free. While at the Peralta Adobe, visitors can also take tours of the Peralta Adobe and the Fallon House, which are $8 for adults, $5 for seniors (62 and older) and students with a valid school identification card; and $5 for children who are accompanied by an adult. -

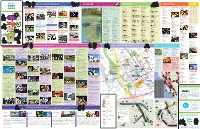

Getting Around Downtown and the Bay Area San Jose

Visit sanjose.org for the Taste wines from mountain terrains and cooled by ocean Here is a partial list of accommodations. Downtown is a haven for the SAN JOSE EVENTS BY THE SEASONS latest event information REGIONAL WINES breezes in one of California’s oldest wine regions WHERE TO STAY For a full list, please visit sanjose.org DOWNTOWN DINING hungry with 250+ restaurants WEATHER San Jose enjoys on average Santa Clara County Fair Antique Auto Show There are over 200 vintners that make up the Santa Cruz Mountain wine AIRPORT AREA - NORTH Holiday Inn San Jose Airport Four Points by Sheraton SOUTH SAN JOSE American/Californian M Asian Fusion Restaurant Gordon Biersch Brewery 300 days of sunshine. LEAGUE SPORTS YEAR ROUND MAY July/August – thefair.org Largest show on the West coast appellation with roots that date back to the 1800s. The region spans from 1350 N. First St. San Jose Downtown 98 S. 2nd Street Restaurant Best Western Plus Clarion Inn Silicon Valley Billy Berk’s historysanjose.org Mt. Madonna in the south to Half Moon Bay in the north. The mountain San Jose, CA 95112 211 S. First St. (408) 418-2230 – $$ 33 E. San Fernando St. Our average high is 72.6˚ F; San Jose Sabercats (Arena Football) Downtown Farmer’s Market Summer Kraftbrew Beer Fest 2118 The Alameda 3200 Monterey Rd. 99 S. 1st St. Japantown Farmer’s Market terrain, marine influences and varied micro-climates create the finest (408) 453-6200 San Jose, CA 95113 (408) 294-6785 – $$ average low is 50.5˚ F.