Supplemental Appendix for “How Does Local TV News Change Viewers’ Attitudes? the Case of Sinclair Broadcasting” This Version: January 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sinclair Broadcast Group Closes on Acquisition of Barrington Stations

Contact: David Amy, EVP & CFO, Sinclair Lucy Rutishauser, VP & Treasurer, Sinclair (410) 568-1500 SINCLAIR BROADCAST GROUP CLOSES ON ACQUISITION OF BARRINGTON STATIONS BALTIMORE (November 25, 2013) -- Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. (Nasdaq: SBGI) (the “Company” or “Sinclair”) announced today that it closed on its previously announced acquisition of 18 television stations owned by Barrington Broadcasting Group, LLC (“Barrington”) for $370.0 million and entered into agreements to operate or provide sales services to another six stations. The 24 stations are located in 15 markets and reach 3.4% of the U.S. TV households. The acquisition was funded through cash on hand. As previously discussed, due to FCC ownership conflict rules, Sinclair sold its station in Syracuse, NY, WSYT (FOX), and assigned its local marketing agreement (“LMA”) and purchase option on WNYS (MNT) in Syracuse, NY to Bristlecone Broadcasting. The Company also sold its station in Peoria, IL, WYZZ (FOX) to Cunningham Broadcasting Corporation (“CBC”). In addition, the license assets of three stations were purchased by CBC (WBSF in Flint, MI and WGTU/WGTQ in Traverse City/Cadillac, MI) and the license assets of two stations were purchase by Howard Stirk Holdings (WEYI in Flint, MI and WWMB in Myrtle Beach, SC) to which Sinclair will provide services pursuant to shared services and joint sales agreements. Following its acquisition by Sinclair, WSTM (NBC) in Syracuse, NY, will continue to provide services to WTVH (CBS), which is owned by Granite Broadcasting, and receive services on WHOI in Peoria, IL from Granite Broadcasting. Sinclair has, however, notified Granite Broadcasting that it does not intend to renew these agreements in these two markets when they expire in March of 2017. -

Updated: 10/21/13 1 2008 Cable Copyright Claims OFFICIAL LIST No. Claimant's Name City State Date Rcv'd 1 Santa Fe Producti

2008 Cable Copyright Claims OFFICIAL LIST Note regarding joint claims: Notation of “(joint claim)” denotes that joint claim is filed on behalf of more than 10 joint copyright owners, and only the entity filing the claim is listed. No. Claimant’s Name City State Date Rcv’d 1 Santa Fe Productions Albuquerque NM 7-1-09 2 (JOINT) American Lives II Film Project, LLC; American Lives film Project, Inc., American Documentaries, Inc., Florenteine Films, & Kenneth L.Burns Walpole NH 7-1-09 3 William D. Rogosin dba Donn Rogosin New York NY 7-1-09 Productions 4 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services St Paul MN 7-1-09 (Tavola Productions LLC) RMW Productions 5 Intermediary Copyright Royalty (Barbacoa, Miami FL 7-1-09 Inc.) 6 WGEM Quincy IL 7-1-09 7 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services Little Rock AK 7-1-09 (Hortus, Ltd) 8 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services New York NY 7-1-09 (Travola Productions LLC), Frappe, Inc. 9 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services, Lakeside MO 7-1-09 Gary Spetz 10 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services, Riverside CT Silver Plume Productions 7-1-09 Updated: 10/21/13 1 11 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services Des Moines IA 7-1-09 (August Home Publishing Company) 12 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Serv (Jose Washington DC 7-1-09 Andres Productions LLC) 13 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Serv (Tavola Productions LLC New York NY 7-1-09 14 Quartet International, Inc. Pearl River NY 7-1-09 15 (JOINT) Hammerman PLLC (Gray Atlanta GA 7-1-09 Television Group Inc); WVLT-TV Inc 16 (JOINT) Intermediary Copyright Royalty Washington DC 7-1-09 Services + Devotional Claimants 17 Big Feats Entertainment L.P. -

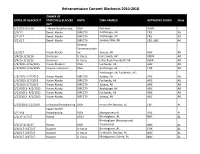

Retrans Blackouts 2010-2018

Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 OWNER OF DATES OF BLACKOUT STATION(S) BLACKED MVPD DMA NAME(S) NETWORKS DOWN State OUT 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH National WGN - 2/3/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV Juneau-Stika, AK CBS, NBC AK General CoMMunication 12/5/17 Vision Alaska Inc. Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Fort SMitH, AK KXUN AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AK KLRA AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Vision Alaska II DISH Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Coastal Television DISH AncHorage, AK FOX AK AncHorage, AK; Fairbanks, AK; 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV AncHorage, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/23/2018-2/2/2018 Lockwood Broadcasting DISH Huntsville-Decatur, AL CW AL SagaMoreHill 5/22/18 Broadcasting DISH MontgoMery AL ABC AL 1/1/17-1/7/17 Hearst AT&T BirMingHaM, AL NBC AL BirMingHaM (Anniston and 3/3/17-4/26/17 Hearst DISH Tuscaloosa) NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse BirMingHaM, AL FOX AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse Huntsville-Decatur, AL NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse MontgoMery-SelMa, AL NBC AL Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH -

Retransmission Consent ) MB Docket No

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 ) In the Matter of ) ) Amendment of the Commission’s Rules ) Related to Retransmission Consent ) MB Docket No. 10-71 ) ) ) ) COMMENTS OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BROADCASTERS NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BROADCASTERS Jane E. Mago Jerianne Timmerman Erin Dozier Scott Goodwin 1771 N Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 429-5430 Sharon Warden Theresa Ottina NAB Research May 27, 2011 Table of Contents I. The Current Market-Based Retransmission Consent System Is an Effective, Efficient and Fair System that Benefits Consumers ............................................................3 II. Limited Revisions to the Retransmission Consent Rules Would Enhance Consumers’ Ability and Freedom to Make Informed Decisions and Would Facilitate Transparency and Carriage-Related Communications .........................................9 A. The FCC Should Extend the Consumer Notice Requirement to All MVPDs ..................................................................................................................10 B. The FCC Should Ensure that Early Termination Fees Do Not Inhibit Consumers’ Ability to Cancel MVPD Service or Switch Providers in the Event of an Impasse in Retransmission Consent Negotiations ..............................13 C. Requiring MVPDs to Submit Current Data on Their Ownership, Operations, and Geographic Coverage Would Facilitate Carriage-Related Communications ....................................................................................................15 -

2006 Cable Copyright Claims Final List

2006 Cable Copyright Claims FINAL LIST Note regarding joint claims: Notation of A(joint claim)@ denotes that joint claim is filed on behalf of more than 10 joint copyright owners, and only the entity filing the claim is listed. Otherwise, all joint copyright owners are listed. Date No Claimant=s Name City State Recvd. 1 Beth Brickell Little Rock Arkansas 7/1/07 2 Moreno/Lyons Productions LLC Arlington Massachusetts 7/2/07 3 Public Broadcasting Service (joint claim) Arlington Virginia 7/2/07 4 Western Instructional Television, Inc. Los Angeles California 7/2/07 5 Noe Corp. LLC Monroe Louisiana 7/2/07 6 MPI Media Productions International, Inc. New York New York 7/2/07 7 In Touch Ministries, Inc. Atlanta Georgia 7/2/07 8 WGEM Quincy Illinois 7/2/07 9 Fox Television Stations, Inc. (WRBW) Washington D.C. 7/2/07 10 Fox Television Stations, Inc. (WOFL) Washington D.C. 7/2/07 11 Fox Television Stations, Inc. (WOGX) Washington D.C. 7/2/07 12 Thomas Davenport dba Davenport Films Delaplane Virginia 7/2/07 13 dick clark productions, inc. Los Angeles California 7/2/07 NGHT, Inc. dba National Geographic 14 Television and Film Washington D.C. 7/2/07 15 Metropolitan Opera Association, Inc. New York New York 7/2/07 16 WSJV Television, Inc. Elkhart Indiana 7/2/07 17 John Hagee Ministries San Antonio Texas 7/2/07 18 Joseph J. Clemente New York New York 7/2/07 19 Bonneville International Corporation Salt Lake City Utah 7/2/07 20 Broadcast Music, Inc. -

Cross-Platform Measurement Helps Local Stations Add Value to Broadcast and Digital

Case Study Cross-Platform Measurement Helps Local Stations Add Value to Broadcast and Digital Ecosystem The local game is changing. Daily deal sites like Groupon and LivingSocial.com in the U.S. have altered the way businesses reach out to consumers. For years, traditional local media – TV, radio and newspapers – has struggled with how to use their websites to complement their offerings and provide more to local businesses. Local TV stations, for example, have typically put video of reports or entire newscasts on their sites. As gateways to local news and events, websites for TV stations typically attract large numbers of visitors, yet it has been difficult to determine the effects and value of those visitors. The challenge has been leveraging “digital touchpoints,” quantifying their benefits and creating new models to attract more from local and national businesses who advertise and encourage those who otherwise might not advertise online at all. As new technology, such as location-based couponing, measurement capabilities, and integrated TV and Internet audience measurement, brings precision to local advertising, marketers are gaining the ability to better package local ad inventory to reach customers and amplify local TV audience value, combining TV and Online. In turn, the precision enables greater efficiency, meaning the opportunity to attract advertisers to spend more, locally. In other words, there’s a fortune to be made in your own backyard. Background Working with this valuable information, Fisher Communications Inc., an innovative local media company with TV, radio, Internet and mobile operations, found themselves positioned to provide their advertiser clients one-stop TV and digital local exposure. -

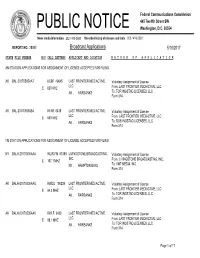

Broadcast Applications 5/10/2017

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 28982 Broadcast Applications 5/10/2017 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING AK BAL-20170505AAT KCBF 49645 LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, Voluntary Assignment of License LLC E 820 KHZ From: LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, LLC AK , FAIRBANKS To: TOR INGSTAD LICENSES, LLC Form 314 AK BAL-20170505ABA KFAR 6438 LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, Voluntary Assignment of License LLC E 660 KHZ From: LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, LLC AK , FAIRBANKS To: ROB INGSTAD LICENSES, LLC Form 314 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING NY BALH-20170505AAA WLIR-FM 61089 LIVINGSTONE BROADCASTING, Voluntary Assignment of License INC. E 107.1 MHZ From: LIVINGSTONE BROADCASTING, INC, NY , HAMPTON BAYS To: VMT MEDIA, INC. Form 314 AK BALH-20170505AAU KWDD 190239 LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, Voluntary Assignment of License LLC E 94.3 MHZ From: LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, LLC AK , FAIRBANKS To: TOR INGSTAD LICENSES, LLC Form 314 AK BALH-20170505AAV KWLF 6439 LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, Voluntary Assignment of License LLC E 98.1 MHZ From: LAST FRONTIER MEDIACTIVE, LLC AK , FAIRBANKS To: TOR INGSTAD LICENSES, LLC Form 314 Page 1 of 17 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. -

2019 Annual Report

A TEAM 2019 ANNU AL RE P ORT Letter to our Shareholders Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. Dear Fellow Shareholders, BOARD OF DIRECTORS CORPORATE OFFICERS ANNUAL MEETING David D. Smith David D. Smith The Annual Meeting of stockholders When I wrote you last year, I expressed my sincere optimism for the future of our Company as we sought to redefine the role of a Chairman of the Board, Executive Chairman will be held at Sinclair Broadcast broadcaster in the 21st Century. Thanks to a number of strategic acquisitions and initiatives, we have achieved even greater success Executive Chairman Group’s corporate offices, in 2019 and transitioned to a more diversified media company. Our Company has never been in a better position to continue to Frederick G. Smith 10706 Beaver Dam Road grow and capitalize on an evolving media marketplace. Our achievements in 2019, not just for our bottom line, but also our strategic Frederick G. Smith Vice President Hunt Valley, MD 21030 positioning for the future, solidify our commitment to diversify and grow. As the new decade ushers in technology that continues to Vice President Thursday, June 4, 2020 at 10:00am. revolutionize how we experience live television, engage with consumers, and advance our content offerings, Sinclair is strategically J. Duncan Smith poised to capitalize on these inevitable changes. From our local news to our sports divisions, all supported by our dedicated and J. Duncan Smith Vice President INDEPENDENT REGISTERED PUBLIC innovative employees and executive leadership team, we have assembled not only a winning culture but ‘A Winning Team’ that will Vice President, Secretary ACCOUNTING FIRM serve us well for years to come. -

Fisher Communications, Inc

UNITEDSTATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON D.C 20549-3010 DIVISION OF CORPORATION FINANCE December 19 2007 Andrew Bor Perkins Coie 1201 Third Avenue Suite 4800 Seattle WA 98101-3099 Re Fisher Communications Inc Incoming letter dated November 29 2007 Dear Mr Bor This is in response to your letters dated November 29 2007 and December 11 2007 concerning the shareholder proposal submitted to Fisher Communications by GAMCO Asset Management Inc We also have received letter from the proponent dated December 2007 Our response is attached to the enclosed photocopy of your correspondence By doing this we avoid having to recite or summarize the facts set forth in the correspondence Copies of all of the correspondence also will be provided to the proponent In connection with this matter your attention is directed to the enclosure which sets forth brief discussion of the Divisions informal procedures regarding shareholder proposals Sincerely Jonathan Ingram Deputy Chief Counsel Enclosures cc Peter Goldstein Director of Regulatory Affairs GAMCO Asset Management Inc One Corporate Center Rye NY 10580-1435-1422 December 19 2007 Response of the Office of Chief Counsel Division of Corporation Finance Re Fisher Communications Inc Incoming letter dated November 29 2007 The proposal relates to acquisitions for view that Fisher Communications There appears to be some basis your may Fisher Communications received it exclude the proposal under rule 14a-8e2 because after the deadline for submitting proposals We note in particular your representations -

Download the SCEC Final Report (Pdf Format)

Seattle Commission on Electronic Communication Steve Clifford Michele Lucien Commission Chair Fisher Communications/KOMO-TV Former CEO, KING Broadcasting Betty Jane Narver Rich Lappenbusch University of Washington Commission Vice Chair Microsoft Amy Philipson UWTV David Brewster Town Hall Vivian Phillips Family Business Margaret Gordon University of Washington Josh Schroeter Founder, Blockbuy.com Bill Kaczaraba NorthWest Cable News Ken Vincent KUOW Radio Norm Langill One Reel Jean Walkinshaw KCTS-TV Commission Staff City Staff Anne Fennessy Rona Zevin Cocker Fennessy City of Seattle Kevin Evanto JoanE O’Brien Cocker Fennessy City of Seattle Table of Contents Final Report Letter from the Commission Chair ......................................................................... 2 Executive Summary .................................................................................................. 3 Diagram of TV/Democracy Portal.......................................................................... 4 Commission Charge & Process ............................................................................... 6 Current Environment................................................................................................. 8 Recommended Goal, Mission Statement & Service Statement...................... 13 Commission Recommendations ............................................................................ 14 Budget & Financing ................................................................................................ 24 Recommended -

2005 Cable Copyright Claims FINAL LIST

2005 Cable Copyright Claims FINAL LIST Note regarding joint claims: Notation of "(joint claim)" denotes that joint claim is filed on behalf of more than 10 joint copyright owners, and only the entity filing the claim is listed. Otherivise, all joint copyright owners are listed. Date toto Claimant's Name City State Recvd. In Touch Ministries, Inc. Atlanta Georgia 7/1/06 Sante Fe Productions Albuquerque New Mexico 7/2/06 3 Gary Spetz/Gary Spetz Watercolors Lakeside Montana 7/2/06 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Washington D.C. 7/3/06 Hortus, Ltd. Little Rock Arkansas 7/3/06 6 Public Broadcasting Service (joint claim) Arlington Virginia 7/3/06 Western Instructional Television, Inc. Los Angeles Califoniia 7/3/06 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services (joint claim) (Devotional Television Broadcasts) Washington D.C. 7/3/06 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services (joint claim) (Syndicated Television Series) Washington D.C. 7/3/06 10 Berkow and Berkow Curriculum Development Chico California 7/3/06 11 Michigan Magazine Company Prescott Michigan 7/3/06 12 Fred Friendly Seminars, Inc. New York Ncw York 7/5/06 Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York dba Columbia University Seminars 13 on Media and Society New York New York 7/5/06 14 The American Lives II Film Project LLC Walpole Ncw Hampshire 7/5/06 15 Babe Winkelman Productions, Inc. Baxter Minnesota 7/5/06 16 Cookie Jar Entertainment Inc. Montreal, Quebec Canada 7/5/06 2005 Cable Copyright Claims FINAL LIST Note regarding joint claims: Notation of."(joint claim)" denotes that joint claim is filed on behalf of more than 10 joint copyright owners, and only the entity filing the claim is listed. -

Seattle a Digital Community Still in Transition Jessica Durkin, Tom Glaisyer, and Kara Hadge, Media Policy Initiative June 2010, Release 2.0

New America Foundation An Information Community Case Study: Seattle A digital community still in transition Jessica Durkin, Tom Glaisyer, and Kara Hadge, Media Policy Initiative June 2010, Release 2.0 Seattle, Washington, could be considered a city singularly suited to develop a healthy democracy in the digital age. The city government, citizens and business have created a productive environment for the next generation of information-sharing and community engagement. Years of economic growth and relative prosperity have fostered new, superior practices in news and information. Yet, losing a major print newspaper, as Seattle did when The Seattle Post-Intelligencer closed, adversely affects a community, by leaving it with one less place to provide public service journalism, stories about people and general community updates. In parallel, Seattle has been at the center of an explosion of alternative news outlets, especially online, which has created a critical mass of information portals for geographic and social communities. As the Knight Report, Informing Communities: Sustaining Democracy in a Digital Age, highlights, it is important to understand that there are three important elements to be considered as we analyze media and democracy in the 21st century: • availability of relevant and credible information to all Americans and their communities; • capacity of individuals to engage with information; and • individual engagement with information and the public life of the community. However, despite the relative vibrancy of the media scene, and even with all its demographic and other advantages, it is unclear how much of this innovation is sustainable. The local web is littered with websites that are no longer updated, and few of the startups boast anything like the journalistic firepower or profitability of the papers of the past.