Retransmission Consent ) MB Docket No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sinclair Broadcast Group Closes on Acquisition of Barrington Stations

Contact: David Amy, EVP & CFO, Sinclair Lucy Rutishauser, VP & Treasurer, Sinclair (410) 568-1500 SINCLAIR BROADCAST GROUP CLOSES ON ACQUISITION OF BARRINGTON STATIONS BALTIMORE (November 25, 2013) -- Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. (Nasdaq: SBGI) (the “Company” or “Sinclair”) announced today that it closed on its previously announced acquisition of 18 television stations owned by Barrington Broadcasting Group, LLC (“Barrington”) for $370.0 million and entered into agreements to operate or provide sales services to another six stations. The 24 stations are located in 15 markets and reach 3.4% of the U.S. TV households. The acquisition was funded through cash on hand. As previously discussed, due to FCC ownership conflict rules, Sinclair sold its station in Syracuse, NY, WSYT (FOX), and assigned its local marketing agreement (“LMA”) and purchase option on WNYS (MNT) in Syracuse, NY to Bristlecone Broadcasting. The Company also sold its station in Peoria, IL, WYZZ (FOX) to Cunningham Broadcasting Corporation (“CBC”). In addition, the license assets of three stations were purchased by CBC (WBSF in Flint, MI and WGTU/WGTQ in Traverse City/Cadillac, MI) and the license assets of two stations were purchase by Howard Stirk Holdings (WEYI in Flint, MI and WWMB in Myrtle Beach, SC) to which Sinclair will provide services pursuant to shared services and joint sales agreements. Following its acquisition by Sinclair, WSTM (NBC) in Syracuse, NY, will continue to provide services to WTVH (CBS), which is owned by Granite Broadcasting, and receive services on WHOI in Peoria, IL from Granite Broadcasting. Sinclair has, however, notified Granite Broadcasting that it does not intend to renew these agreements in these two markets when they expire in March of 2017. -

Updated: 10/21/13 1 2008 Cable Copyright Claims OFFICIAL LIST No. Claimant's Name City State Date Rcv'd 1 Santa Fe Producti

2008 Cable Copyright Claims OFFICIAL LIST Note regarding joint claims: Notation of “(joint claim)” denotes that joint claim is filed on behalf of more than 10 joint copyright owners, and only the entity filing the claim is listed. No. Claimant’s Name City State Date Rcv’d 1 Santa Fe Productions Albuquerque NM 7-1-09 2 (JOINT) American Lives II Film Project, LLC; American Lives film Project, Inc., American Documentaries, Inc., Florenteine Films, & Kenneth L.Burns Walpole NH 7-1-09 3 William D. Rogosin dba Donn Rogosin New York NY 7-1-09 Productions 4 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services St Paul MN 7-1-09 (Tavola Productions LLC) RMW Productions 5 Intermediary Copyright Royalty (Barbacoa, Miami FL 7-1-09 Inc.) 6 WGEM Quincy IL 7-1-09 7 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services Little Rock AK 7-1-09 (Hortus, Ltd) 8 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services New York NY 7-1-09 (Travola Productions LLC), Frappe, Inc. 9 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services, Lakeside MO 7-1-09 Gary Spetz 10 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services, Riverside CT Silver Plume Productions 7-1-09 Updated: 10/21/13 1 11 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services Des Moines IA 7-1-09 (August Home Publishing Company) 12 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Serv (Jose Washington DC 7-1-09 Andres Productions LLC) 13 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Serv (Tavola Productions LLC New York NY 7-1-09 14 Quartet International, Inc. Pearl River NY 7-1-09 15 (JOINT) Hammerman PLLC (Gray Atlanta GA 7-1-09 Television Group Inc); WVLT-TV Inc 16 (JOINT) Intermediary Copyright Royalty Washington DC 7-1-09 Services + Devotional Claimants 17 Big Feats Entertainment L.P. -

2006 Cable Copyright Claims Final List

2006 Cable Copyright Claims FINAL LIST Note regarding joint claims: Notation of A(joint claim)@ denotes that joint claim is filed on behalf of more than 10 joint copyright owners, and only the entity filing the claim is listed. Otherwise, all joint copyright owners are listed. Date No Claimant=s Name City State Recvd. 1 Beth Brickell Little Rock Arkansas 7/1/07 2 Moreno/Lyons Productions LLC Arlington Massachusetts 7/2/07 3 Public Broadcasting Service (joint claim) Arlington Virginia 7/2/07 4 Western Instructional Television, Inc. Los Angeles California 7/2/07 5 Noe Corp. LLC Monroe Louisiana 7/2/07 6 MPI Media Productions International, Inc. New York New York 7/2/07 7 In Touch Ministries, Inc. Atlanta Georgia 7/2/07 8 WGEM Quincy Illinois 7/2/07 9 Fox Television Stations, Inc. (WRBW) Washington D.C. 7/2/07 10 Fox Television Stations, Inc. (WOFL) Washington D.C. 7/2/07 11 Fox Television Stations, Inc. (WOGX) Washington D.C. 7/2/07 12 Thomas Davenport dba Davenport Films Delaplane Virginia 7/2/07 13 dick clark productions, inc. Los Angeles California 7/2/07 NGHT, Inc. dba National Geographic 14 Television and Film Washington D.C. 7/2/07 15 Metropolitan Opera Association, Inc. New York New York 7/2/07 16 WSJV Television, Inc. Elkhart Indiana 7/2/07 17 John Hagee Ministries San Antonio Texas 7/2/07 18 Joseph J. Clemente New York New York 7/2/07 19 Bonneville International Corporation Salt Lake City Utah 7/2/07 20 Broadcast Music, Inc. -

1 Curriculum Vitae Philip Matthew Stinson, Sr. 232

CURRICULUM VITAE PHILIP MATTHEW STINSON, SR. 232 Health & Human Services Building Criminal Justice Program Department of Human Services College of Health & Human Services Bowling Green State University Bowling Green, Ohio 43403-0147 419-372-0373 [email protected] I. Academic Degrees Ph.D., 2009 Department of Criminology College of Health & Human Services Indiana University of Pennsylvania Indiana, PA Dissertation Title: Police Crime: A Newsmaking Criminology Study of Sworn Law Enforcement Officers Arrested, 2005-2007 Dissertation Chair: Daniel Lee, Ph.D. M.S., 2005 Department of Criminal Justice College of Business and Public Affairs West Chester University of Pennsylvania West Chester, PA Thesis Title: Determining the Prevalence of Mental Health Needs in the Juvenile Justice System at Intake: A MAYSI-2 Comparison of Non- Detained and Detained Youth Thesis Chair: Brian F. O'Neill, Ph.D. J.D., 1992 David A. Clarke School of Law University of the District of Columbia Washington, DC B.S., 1986 Department of Public & International Affairs College of Arts and Sciences George Mason University Fairfax, VA A.A.S., 1984 Administration of Justice Program Northern Virginia Community College Annandale, VA 1 II. Academic Positions Professor, 2019-present (tenured) Associate Professor, 2015-2019 (tenured) Assistant Professor, 2009-2015 (tenure track) Criminal Justice Program, Department of Human Services Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH Assistant Professor, 2008-2009 (non-tenure track) Department of Criminology Indiana University of -

Northwest Ohio Emergency Alert System

NORTHWEST OHIO EMERGENCY ALERT SYSTEM OPERATIONAL AREA PLAN ASHTABULA LAKE LUCAS FULTON WILLIAMS OTTAWA GEAUGA CUYAHOGA DEFIANCE SANDUSKY ERIE TRUMBULL HENRY WOOD LORAIN PORTAGE SUMMIT HURON MEDINA PAULDING SENECA PUTNAM MAHONING HANCOCK ASHLAND VAN WERT WYANDOT CRAWFORD WAYNE STARK COLUMBIANA ALLEN RICHLAND ‘ HARDIN CARROLL MERCER MARION HOLMES AUGLAIZE MORROW TUSCARAWAS JEFFERSON KNOX LOGAN COSHOCTON SHELBY UNION HARRISON DELAWARE DARKE LICKING CHAMPAIGN GUERNSEY MIAMI MUSKINGUM BELMONT FRANKLIN CLARK MONTGOMERY MADISON PERRY MONROE PREBLE FAIRFIELD NOBLE GREENE PICKAWAY MORGAN FAYETTE HOCKING WASHINGTON BUTLER WARREN CLINTON ATHENS ROSS VINTON HAMILTON HIGHLAND CLERMONT MEIGS PIKE JACKSON GALLIA BROWN ADAMS SCIOTO LAWRENCE LUCAS FULTON WILLIAMS OTTAWA DEFIANCE SANDUSKY HENRY WOOD SENECA EMERGENCY ALERT SYSTEM NORTHWEST OHIO OPERATIONAL AREA PLAN AND PROCEDURES FOR THE FOLLOWING OHIO COUNTIES DEFIANCE FULTON HENRY LUCAS OTTAWA SANDUSKY SENECA WILLIAMS WOOD Revised December 2003 Ohio Emergency Management Agency (EMA) (20) All Northwest Ohio Operational Area County EMA Directors All Northwest Ohio Operational Area County Sheriffs Monroe County Emergency Management Agency, Michigan Michigan State Emergency Management Agency All EAS Northwest Ohio Operational Area Radio and TV Stations All Northwest Ohio Cable TV Systems Ohio SECC Chairman Ohio SECC Cable Co-Chairman Operational Area LECC Chairman Operational Area LECC Vice Chairman Federal Communications Commission (FCC) National Weather Service - Cleveland National Weather Service - Fort Wayne, IN Ohio Educational Telecommunications Network Commission (OET) Ohio Cable Telecommunications Association (OCTA) Ohio Association of Broadcasters (OAB) Michigan SECC Chairman Additional copies are available from: Ohio Emergency Management Agency 2855 West Dublin Granville Road Columbus, Ohio 43235-2206 (614) 889-7150 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. PURPOSE ...................................................................................................................... 1 II. -

2005 Cable Copyright Claims FINAL LIST

2005 Cable Copyright Claims FINAL LIST Note regarding joint claims: Notation of "(joint claim)" denotes that joint claim is filed on behalf of more than 10 joint copyright owners, and only the entity filing the claim is listed. Otherivise, all joint copyright owners are listed. Date toto Claimant's Name City State Recvd. In Touch Ministries, Inc. Atlanta Georgia 7/1/06 Sante Fe Productions Albuquerque New Mexico 7/2/06 3 Gary Spetz/Gary Spetz Watercolors Lakeside Montana 7/2/06 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Washington D.C. 7/3/06 Hortus, Ltd. Little Rock Arkansas 7/3/06 6 Public Broadcasting Service (joint claim) Arlington Virginia 7/3/06 Western Instructional Television, Inc. Los Angeles Califoniia 7/3/06 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services (joint claim) (Devotional Television Broadcasts) Washington D.C. 7/3/06 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services (joint claim) (Syndicated Television Series) Washington D.C. 7/3/06 10 Berkow and Berkow Curriculum Development Chico California 7/3/06 11 Michigan Magazine Company Prescott Michigan 7/3/06 12 Fred Friendly Seminars, Inc. New York Ncw York 7/5/06 Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York dba Columbia University Seminars 13 on Media and Society New York New York 7/5/06 14 The American Lives II Film Project LLC Walpole Ncw Hampshire 7/5/06 15 Babe Winkelman Productions, Inc. Baxter Minnesota 7/5/06 16 Cookie Jar Entertainment Inc. Montreal, Quebec Canada 7/5/06 2005 Cable Copyright Claims FINAL LIST Note regarding joint claims: Notation of."(joint claim)" denotes that joint claim is filed on behalf of more than 10 joint copyright owners, and only the entity filing the claim is listed. -

New Channel Lineup

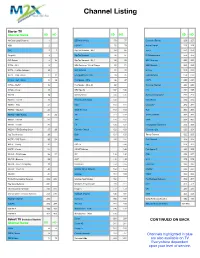

Channel Listing Starter TV Channel Name SD HD SD HD SD HD McClure Local Channel 1 ESPN University 76 77 Discovery Family 226 227 HSN 2 ESPN 2 78 79 Animal Planet 228 229 QVC 3 7 Big Ten Network - Alt 2 84 85 TruTV 252 253 ShopHQ 4 Big Ten Network 86 87 E! Entertainment 254 255 CW-Toledo 5 15 Big Ten Network - Alt 1 88 89 BBC America 260 261 WTOL - Grit 9 NFL Redzone * Extra Charge 90 91 A&E Network 262 263 WTOL - Justice Network 10 NFL Network 92 93 History 268 269 WTOL - CBS Toledo 11 12 Fox SportsTime Ohio 94 95 Food Network 278 279 WTVG - ABC Toledo 13 14 Fox Sports - Ohio 96 97 HGTV 280 281 WTVG - MeTV 16 Fox Sports - Ohio Alt 98 Cooking Channel 282 283 WTVG - Circle 17 NBC Sports 102 103 DIY 284 285 WNHO 19 MLB Network 104 105 National Geographic 292 293 WNWO - Comet 20 Paramount Network 108 MotorTrend 294 295 WNWO - TBD 21 USA 110 111 Discovery 296 297 WNWO - Stadium 22 WGN America 112 113 TLC 300 301 WNWO - NBC Toledo 24 23 TNT 114 115 Travel Channel 302 303 WBGU - Encore 25 TBS 116 117 OWN 304 305 WBGU - Create 26 FX 120 121 Investigation Discovery 308 309 WBGU - PBS Bowling Green 27 28 Comedy Central 122 123 Discovery Life 320 321 You Too America 29 Syfy 124 125 Tennis Channel 322 323 WGTE - PBS Toledo 30 31 Bravo 130 131 Golf Channel 324 325 WGTE - Family 32 AXS TV 144 FXX 328 329 WGTE - Create 33 HDNET Movies 145 Fox Sports 1 332 333 WUPW - FOX Toledo 36 37 IFC 146 147 CNN 376 377 WUPW - Bounce 38 AMC 148 149 HLN 378 379 WUPW - Court TV Mystery 39 Sundance 154 155 Fox News 384 385 WUPW - Court TV 40 Lifetime Movie Network 162 -

Lenawee County Monroe County

LOCAL CHANNEL LINEUP CHANGES EFFECTIVE 1/1/2021 (negotiations ongoing) Lenawee County Monroe County 2 – WJBK Fox 2 Detroit 2 – WJBK Fox 2 Detroit 3 – WYMD MYTV 20 Detroit 3 – WYMD MYTV 20 Detroit 4 – WDIV NBC 4 Detroit 4 – WDIV NBC 4 Detroit 5 – WKBD CW 50 Detroit 5 – WKBD CW 50 Detroit 6 – WUPW FOX 36 Toledo 7 – WXYZ ABC 7 Detroit 7 – WXYZ ABC 7 Detroit 8 – WNWO NBC 24 Toledo 8 – WNWO NBC 24 Toledo 9 – CBET CBC 9 Canada 9 – CBET CBC 9 Canada 10 – WWJTV CBS 62 Detroit 10 – WWJTV CBS 62 Detroit 11 – WTOL CBS 11 Toledo 11 – WTOL CBS 11 Toledo 12 – WGTV PBS 30 Toledo 12 – WGTV PBS 30 Toledo 13 – WTVG ABC 13 Toledo 13 – WTVG ABC 13 Toledo 14 – WTVS PBS 56 Detroit 14 – WTVS PBS 56 Detroit 15 – WPXD ION 31 Ann Arbor 15 – WPXD ION 31 Ann Arbor 17 – QUBO Ann Arbor 17 – QUBO Ann Arbor 20 – WLMB TV 40 Toledo 20 – WLMB TV 40 Toledo 84 – CW13 Toledo 84 – CW13 Toledo 85 – START Detroit 85 – START Detroit 87 – WGTE PBS Kids Toledo 87 – WGTE PBS Kids Toledo 88 – WGTE PBS Create Toledo 88 – WGTE PBS Create Toledo 89 – STADIUM Toledo 89 – STADIUM Toledo 90 – WTVG Weather Toledo 90 – WTVG Weather Toledo 92 – MOVIES! Detroit 91 – BOUNCE Toledo 94 – BOUNCE Detroit 92 – MOVIES! Detroit 95 – LAFF Detroit 93 – MYSTERY Toledo 96 – TRUE CRIME NETWORK Toledo 94 – BOUNCE Detroit 97 – GRIT Toledo 95 – LAFF Detroit 98 – WTVS PBS Create Detroit 96 – TRUE CRIME NETWORK Toledo 99 – ION LIFE Ann Arbor 97 – GRIT Toledo 109 – COMET Toledo 98 – WTVS PBS Create Detroit 110 – TBD WNWO Toledo 99 – ION LIFE Ann Arbor 111 – BUZZR Detroit 109 – COMET Toledo 112 – HEROES & ICONS Detroit 110 – TBD WNWO Toledo 113 – THIS 4 Detroit 111 – BUZZR Detroit 114 – WTVS PBS Kids Detroit 112 – HEROES & ICONS Detroit 115 – WTVS PBS World Detroit 113 – THIS 4 Detroit 116 – ANTENNA Detroit 114 – WTVS PBS Kids Detroit 117 – MYSTERY Detroit 115 – WTVS PBS World Detroit 118 – METV Detroit 116 – ANTENNA Detroit 119 – WLMB 2 Toledo 117 – MYSTERY Detroit 120 – COZI Detroit 118 – METV Detroit 121 – QUEST Toledo 119 – WLMB 2 Toledo 120 – COZI Detroit 121 – QUEST Toledo *Channels Removed. -

All Full-Power Television Stations by Dma, Indicating Those Terminating Analog Service Before Or on February 17, 2009

ALL FULL-POWER TELEVISION STATIONS BY DMA, INDICATING THOSE TERMINATING ANALOG SERVICE BEFORE OR ON FEBRUARY 17, 2009. (As of 2/20/09) NITE HARD NITE LITE SHIP PRE ON DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LITE PLUS WVR 2/17 2/17 LICENSEE ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX NBC KRBC-TV MISSION BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX CBS KTAB-TV NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX FOX KXVA X SAGE BROADCASTING CORPORATION ABILENE-SWEETWATER SNYDER TX N/A KPCB X PRIME TIME CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING, INC ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (DIGITALKTXS-TV ONLY) BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. ALBANY ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC ALBANY ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC ALBANY CORDELE GA IND WSST-TV SUNBELT-SOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS LTD ALBANY DAWSON GA PBS WACS-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY PELHAM GA PBS WABW-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY VALDOSTA GA CBS WSWG X GRAY TELEVISION LICENSEE, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY AMSTERDAM NY N/A WYPX PAXSON ALBANY LICENSE, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY PBS WMHT WMHT EDUCATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. -

I. Tv Stations

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) MB Docket No. 17- WSBS Licensing, Inc. ) ) ) CSR No. For Modification of the Television Market ) For WSBS-TV, Key West, Florida ) Facility ID No. 72053 To: Office of the Secretary Attn.: Chief, Policy Division, Media Bureau PETITION FOR SPECIAL RELIEF WSBS LICENSING, INC. SPANISH BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC. Nancy A. Ory Paul A. Cicelski Laura M. Berman Lerman Senter PLLC 2001 L Street NW, Suite 400 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (202) 429-8970 April 19, 2017 Their Attorneys -ii- SUMMARY In this Petition, WSBS Licensing, Inc. and its parent company Spanish Broadcasting System, Inc. (“SBS”) seek modification of the television market of WSBS-TV, Key West, Florida (the “Station”), to reinstate 41 communities (the “Communities”) located in the Miami- Ft. Lauderdale Designated Market Area (the “Miami-Ft. Lauderdale DMA” or the “DMA”) that were previously deleted from the Station’s television market by virtue of a series of market modification decisions released in 1996 and 1997. SBS seeks recognition that the Communities located in Miami-Dade and Broward Counties form an integral part of WSBS-TV’s natural market. The elimination of the Communities prior to SBS’s ownership of the Station cannot diminish WSBS-TV’s longstanding service to the Communities, to which WSBS-TV provides significant locally-produced news and public affairs programming targeted to residents of the Communities, and where the Station has developed many substantial advertising relationships with local businesses throughout the Communities within the Miami-Ft. Lauderdale DMA. Cable operators have obviously long recognized that a clear nexus exists between the Communities and WSBS-TV’s programming because they have been voluntarily carrying WSBS-TV continuously for at least a decade and continue to carry the Station today. -

Broadcasters in the Internet Age

G.research, LLC November 27, 2018 One Corporate Center Rye, NY 10580-1422 g.research Tel (914) 921-5150 www.gabellisecurities.com Broadcasters in the Internet Age Brett Harriss G.research, LLC 2018 (914) 921-8335 -Please Refer To Important Disclosures On The Last Page Of This Report- G.research, LLC November 27, 2018 One Corporate Center Rye, NY 10580-1422 g.research Tel (914) 921-5150 www.gabellisecurities.com OVERVIEW The television industry is experiencing a tectonic shift of viewership from linear to on-demand viewing. Vertically integrated behemoths like Netflix and Amazon continue to grow with no end in sight. Despite this, we believe there is a place in the media ecosystem for traditional terrestrial broadcast companies. SUMMARY AND OPINION We view the broadcasters as attractive investments. We believe there is the potential for consolidation. On April 20, 2017, the FCC reinstated the Ultra High Frequency (UHF) discount giving broadcasters with UHF stations the ability to add stations without running afoul of the National Ownership Cap. More importantly, the current 39% ownership cap is under review at the FCC. Given the ubiquitous presence of the internet which foster an excess of video options and media voices, we believe the current ownership cap could be viewed as antiquated. Should the FCC substantially change the ownership cap, we would expect consolidation to accelerate. Broadcast consolidation would have the opportunity to deliver substantial synergies to the industry. We would expect both cost reductions and revenue growth, primarily in the form of increased retransmission revenue, to benefit the broadcast stations and networks. -

Original Llp

EX PARTE OR LATE FILED HOGAN &HAKrsoN ORIGINAL LLP. DOCKET FILE COpy ORIGINAL COLUWBIA SQUARE 5511 THIRTEENTH STREET, NW MACE J. IOIINSTIIN WASHINGTON, DC 20004-1109 'AUNI.. DlDer DIAL (202) 631-M77 TIL (102) 657-6800 October 27, 1995 RECE/~D) 637·5910 OCl271995 BYHAND DELIVERY fal£RAL =~~i~~~:-S8ION The Secretary Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 Re: Notice ofEx Parte Presentation in MM Docket No. 93-48, Policies and Rules Concerning Children's Television Programming Dear Sir: Notice is hereby given that on October 26, 1995, representatives ofFox Broadcasting Company ("FBC") and its subsidiary, the Fox Children's Network ("FCN"), and the Fox Affiliates Association met with Commissioners James H. Quello and Rachelle B. Chong, Chiefof StaffBlair Levin, Counsel to the Chairman Julius Genachowski, and Legal Advisors Jane Mago, David R. Siddall and Lisa B. Smith in connection with the above-referenced proceeding. The meetings were attended by the following: Preston R. Padden, President, Network Distribution Fox Broadcasting Company Peggy K. Binzel, Senior Vice President - Government Relations The News Corporation Limited Margaret Loesch, President Fox Children's Network Patrick Mullen, Vice-Chairman Fox Affiliates Association Stuart Powell, Chairman, FCN Oversight Committee Fox Affiliates Association No. of Copiee rec'd CJd-/ ListABCDE --. LOItDON ...... I'IIAGW WMMW UL'l'DIOa,Ie .-rHaIM,lID OOLOIIADO U'IIINOI, 00 ......00 1iICUAN. VA •AJ/IIiI1IM CJIiDI HOGAN &HAlrrsoN L.L.P. The Secretary October 27, 1995 Page 2 The purpose ofthe meetings was to present and discuss (1) the results ofa survey ofthe types and amount of children's educational and informational programming broadcast by FCN and its affiliates, and (2) a videotape featuring examples ofthe children's educational and informational programming produced by FCN.