HLB 25 2 BOOK.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ken Lopez Bookseller Modern Literature 165 1 Lopezbooks.Com

MODERN LITERATURE 165 KEN LOPEZ BOOKSELLER MODERN LITERATURE 165 1 LOPEZBOOKS.COM KEN LOPEZ BOOKSELLER MODERN LITERATURE 165 2 KEN LOPEZ, Bookseller MODERN LITERATURE 165 51 Huntington Rd. Hadley, MA 01035 (413) 584-4827 FAX (413) 584-2045 [email protected] | www.lopezbooks.com 1. (ABBEY, Edward). The 1983 Western Wilderness Calendar. (Salt Lake City): (Dream Garden) CATALOG 165 — MODERN LITERATURE (1982). The second of the Wilderness calendars, with text by Abbey, Tom McGuane, Leslie Marmon Silko, All books are first printings of the first edition or first American edition unless otherwise noted. Our highest Ann Zwinger, Lawrence Clark Powell, Wallace Stegner, grade is fine. Barry Lopez, Frank Waters, William Eastlake, John New arrivals are first listed on our website. For automatic email notification about specific titles, please create Nichols, and others, as well as work by a number of an account at our website and enter your want list. To be notified whenever we post new arrivals, just send your prominent photographers. Each day is annotated with email address to [email protected]. a quote, a birthday, or an anniversary of a notable event, most pertaining to the West and its history and Books can be ordered through our website or reserved by phone or e-mail. New customers are requested to pay natural history. A virtual Who’s Who of writers and in advance; existing customers may pay in 30 days; institutions will be billed according to their needs. All major photographers of the West, a number of them, including credit cards accepted. Any book may be returned for any reason within 30 days, but we request notification. -

The Glass Case Modern Literature Published After 1900

The Glass Case Modern Literature Published After 1900 On-Line Only: Catalogue # 209 Second Life Books Inc. ABAA- ILAB P.O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA 01237 413-447-8010 fax: 413-499-1540 Email: [email protected] The Glass Case: Modern Literature Terms : All books are fully guaranteed and returnable within 7 days of receipt. Massachusetts residents please add 5% sales tax. Postage is additional. Libraries will be billed to their requirements. Deferred billing available upon request. We accept MasterCard, Visa and American Express. ALL ITEMS ARE IN VERY GOOD OR BETTER CONDITION , EXCEPT AS NOTED . Orders may be made by mail, email, phone or fax to: Second Life Books, Inc. P. O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA. 01237 Phone (413) 447-8010 Fax (413) 499-1540 Email:[email protected] Search all our books at our web site: www.secondlifebooks.com or www.ABAA.org . 1. ABBEY, Edward. DESERT SOLITAIRE, A season in the wilderness. NY: McGraw-Hill, (1968). First Edition. 8vo, pp. 269. Drawings by Peter Parnall. A nice copy in little nicked dj. Scarce. [38528] $1,500.00 A moving tribute to the desert, the personal vision of a desert rat. The author's fourth book and his first work of nonfiction. This collection of meditations by then park ranger Abbey in what was Arches National Monument of the 1950s was quietly published in a first edition of 5,000 copies ONE OF 10 COPIES, AUTHOR'S FIRST BOOK 2. ADAMS, Leonie. THOSE NOT ELECT. NY: Robert M. McBride, 1925. First Edition. -

Catalogue #19

Back of Beyond Books proudly releases Catalogue #19. We continue to feature books and ephemera from the American West but you’ll also find numerous pages of Americana, Travel and Photographic material along with Explora- tion, Mining and Native Americana. We’ve also picked up small collections of Poetry and Art Books which have been fun to catalogue. Perhaps my favorite genre of Catalogue #19 are the 21 Promotional items from western states and communities. These colorful pamphlets, mostly from the early 20th century, would make any Chamber of Commerce proud. It’s always interesting to see what items sell quickly in each catalogue. I of- ten guess wrong so I’ll leave the decisions up to you. Several items of note, however, include: The best association copy known of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian--inscribed to Edward Abbey, a beautifully bright advertising poster for the ‘Field Self Discharging Rake’, a scarce promotional for the Salt River Valley of Arizona, a full-plate tintype from Volcano, California, and six large format albumen photographs depicting archaeological sites of Arizona and New Mexico by John K. Hillers. I’m also taken with the striking and rare Broadside for the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad, the very clean re- view copy of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and the atlas from the Pike Expe- dition published in 1810. Thanks to my staff at the store for working around the piles and boxes of books. If you’re ever in Moab our shop is open daily; please stop in. Sophie Tomkiewicz used the skills she learned at the Colorado Rare Books School in developing Catalogue #19 and Eric Trenbeath is our designer. -

Table of Contents

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 38, 1959-1960 Table Of Contents OFFICERS............................................................................................................5 PAPERS THE COST OF A HARVARD EDUCATION IN THE PURITAN PERIOD..........................7 BY MARGERY S. FOSTER THE HARVARD BRANCH RAILROAD, 1849-1855..................................................23 BY ROBERT W. LOVETT RECOLLECTIONS OF THE CAMBRIDGE SOCIAL DRAMATIC CLUB........................51 BY RICHARD W. HALL NATURAL HISTORY AT HARVARD COLLEGE, 1788-1842......................................69 BY JEANNETTE E. GRAUSTEIN THE REVEREND JOSE GLOVER AND THE BEGINNINGS OF THE CAMBRIDGE PRESS.............................................................................87 BY JOHN A. HARNER THE EVOLUTION OF CAMBRIDGE HEIGHTS......................................................111 BY LAURA DUDLEY SAUNDERSON THE AVON HOME............................................................................................121 BY EILEEN G. MEANY MEMORIAL BREMER WHIDDON POND...............................................................................131 BY LOIS LILLEY HOWE ANNUAL REPORTS.............................................................................................133 MEMBERS..........................................................................................................145 THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY PROCEEDINGS FOR THE YEARS 1959-60 LIST OF OFFICERS FOR THESE TWO YEARS 1959 President Mrs. George w. -

The Hundredth Book

THE HUNDREDTH A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BOOK CLUB OF CALIFORNIA & A HISTORY OF THE CLUB BY DAVID MAGEE 1958 PRINTED AT THE GRABHORN PRESS FOR THE BOOK CLUB OF CALIFORNIA CONTENTS PREFATORY NOTE page v A HISTORY OF THE BOOK CLUB OF CALIFORNIA page vii OFFICERS OF THE CLUB page xxv THE HUNDRED BOOKS page 1 ANNUAL KEEPSAKES page 55 MISCELLANEOUS KEEPSAKES page 71 QUARTERLY NEWS-LETTER page 74 INDEX page 75 copyright 1958 by the book club of california PREFATORY NOTE IBLIOGRAPHIES are seldom solo performances. A man’s name may appear on a title-page, but that tells only one half of the story. It is the purpose of this prefatory note to tell the other half. When I agreed to compile a bibliography of The Book Club of California publications, with an accompanying history of the Club, I thought I was in for a fairly easy job. I understood that the archives were in existence and, of course, on the shelves at headquarters were complete files of Club books, keepsakes, Quarterly News-Letters, etc. It should be simple, merely a matter of collating and checking and trying to make of a bibliography something more than a catalogue of titles. How wrong can a person be? To begin with, it must be understood that for many years the Club was run by amateurs, devoted, splendid citizens who attended monthly board meetings and when it was necessary gave generously of their time and energies for the welfare of the Club. But they were still amateurs, and so long as the organization was not in danger of collapse or actual decease they were content to let things jog along. -

The Antiquarian Book Glossary

The Antiquarian Book Glossary Version 1.1 Books Tell You Why 1265 Chrismill Lane Mt. Pleasant, SC www.BooksTellYouWhy.com [email protected] (843) 849-0283 Contents Introduction..3 Glossary...4 Index...37 Additional Info...42 2 Introduction Thank you for your interest in Books Tell You Why and welcome to our Anti- quarian Book Glossary. We couldn’t be more pleased you’ve selected us as your source for information about rare book collecting, and we hope that this downloadable guide helps address your questions and concerns about the field of antiquarian books. The following glossary is designed to provide you with an entry-level resource for commonly used terms and concepts in the rare book world. While our aim is to offer as comprehensive a guide as possible, please note this docu- ment is merely a primer of rare book and manuscript collecting, and should be used as more of an introductory text rather than a definitive guide to the purchasing and collecting of rare books. For additional information and resources about our glossary, books, or ser- vices, please don't hesitate to: Visit us online at www.BooksTellYouWhy.com Contact us via email at [email protected] Call us at (800) 948-5563. Once again, thank you for your interest in Books Tell You Why. We wish you the best of luck in your collecting journey. 3 A ABAA The Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America was founded in 1949 to promote interest in rare books and foster collegial relations. They maintain the highest standards in the trade. -

Fine Printing & Small Presses A

Fine Printing & Small Presses A - K Catalogue 354 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.williamreesecompany.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are consid- ered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering and a Fax machine for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inven- tory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment. Institutional billing requirements may, as always, be accommodated upon request. -

Eben Francis Thompson

I94O-] OBITUARIES 15 After a course at the Harvard Law School, he entered practice in the office of Herbert Parker, former attorney-general of Massa- chusetts. In 1908 he joined Frank C. Smith, Jr., to form the firm of Smith & Gaskill, six years later uniting with Charles M. Thayer under the name of Thayer, Smith & Gaskill. This partner- ship became one of the leading law firms in Worcester, Mr. Gaskill himself specializing in business law. He was a director of several local banks, and president of the People's Savings Bank from 1918 to 1933. He was treasurer of Worcester Academy, active in relief work during the World War, and senior warden of All Saints Church, all of which positions he gave up in 1933 at the time of his retirement from active business because of ill health. He married, June i, 1905, Caroline Dewey Nichols, who was the daughter of the late President of this Society, Dr. Charles L. Nichols, and who died in 1933. Mr. Gaskill died February 10, 1940, being survived by three children—Charles Francis Gaskill, Mrs. William A. Wheeler, and Caroline N. Gaskill. Mr. Gaskill was elected to the American Antiquarian Society in 1917 and was a constant attendant at its meetings. He was also a member of the Club of Odd Volumes of Boston. Inheriting a fine library of English literature from his father, he became much interested in book collecting, especially in the publications of the Strawberry Hill press. He was popular socially and his retirement from active life seven years before his death was the cause of sin- cere regret on the part of his many friends. -

The Annals of the Four Masters De Búrca Rare Books Download

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 142 Summer 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 142 Summer 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Four Masters is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 142: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our cover illustration is taken from item 70, Owen Connellan’s translation of The Annals of the Four Masters. -

An Association Copy of Note: Willa Cather's Copy of Aucassin & Nicolete

An Association Copy of Note: Willa Cather’s copy of Aucassin & Nicolete From 1896 to 1906 the renown American writer and novelist, Willa Cather, resided in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Twelve novels with now more or less familiar titles like O Pioneers! (1913), The Song of the Lark (1915), and Death comes for the Archbishop (1927) thrilled American readers. Long before her novels, however, there were more modest achievements such as her first and only book of poetry, April Twilights (1903), her first collection of short story fiction, The Troll Garden (1905) and her work as editor of Home Monthly, the magazine which brought her to Pittsburgh in the first place. In 1898 she began work at the Pittsburgh Daily Leader but then in 1901 she took a job teaching high school students in Pittsburgh. Teaching would not become her mainstay and by 1906 she was ready to move on to a job at McClure’s Magazine in New York City which eventually would lead to her becoming its managing editor. McClure’s was one of America’s most successful and popular literary magazines, and it was while in New York that Cather would meet her lifelong companion, Edith Lewis. But wait, we’re getting a bit ahead of ourselves. It’s those Pittsburgh years that are of the most direct concern for this brief essay. Willa Cather often referred to Pittsburgh as the “birthplace” of her writing career, and the very reason why the essay exists at all is because of a little book found from those natal literary years. We have to go back to September 18, 2012 when I came across the notice from an upper Mid-Western book dealer advertised a little Mosher book which he said was from Willa Cather’s library: Aucassin & Nicolete. -

Short-Title Catalogs: the Current State of Play

SHORT TITLE CATALOGUES: THE CURRENT STATE OF PLAY 121 KRK Short-Title Catalogs: The Current State of Play John Bloomberg-Rissman he output of the Anglophone press is covered by a series of projects, loosely known as short title catalogs. The major projects include: T l A Short-Title Catalogue of Books Printed in England, Scotland, & Ireland and of English Books Printed Abroad 1475–1640 (STC) 1 Short-Title Catalogue of Books Printed in England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and British America and of English Books Printed in Other Countries 1641 1700 (Wing) 1 The English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC) 1 The Nineteenth Century Short Title Catalogue (NSTC) 1 The North American Imprints Program (NAIP) There are other short title catalog projects, such as the Cathedral Libraries Catalogue and English Catholic Books, 1701–1800 to name but two. Though these projects, and others like them, are arguably as worthy of discussion as any, it is not incorrect to see them as extensions of or supplements to the projects listed above. Volume 1 of the Cathedral Libraries Catalogue is in essence an extension of the can vass undertaken for STC and Wing, while volume 2 concerns itself with continen tal printing, and is therefore irrelevant in this context. English Catholic Books, 1701– 1800 is, in its own words, “a useful adjunct to the ESTC.”1 This paper will limit itself then to discussion of the bulleted projects, and will include up-to-date information on the status of each. The precursor to the first true short title catalog in the Anglophone world is usually considered to be the three-volume Catalogue of Books in the Library of the British Museum Printed in England, Scotland, and Ireland, and of Books in English Printed John Bloomberg-Rissman is Assistant Director for English projects (ESTC), Center for Bibliographical Studies and Research at the University of California, Riverside 121 122 RARE BOOKS & MANUSCRIPTS LIBRARIANSHIP Abroad, to the Year 1640 (Trustees of the British Museum, 1884). -

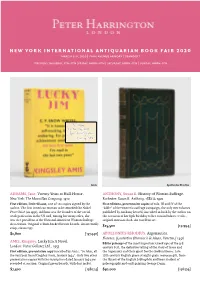

NEW YORK INTERNATIONAL Antiquarian BOOK FAIR 2020 March 5–8, 2020 | Park Avenue Armory | Stand E17

NEW YORK INTERNATIONAL ANTIquARIAN BOOK FAIR 2020 march 5–8, 2020 | park avenue armory | stand e17 (preview) thursday, 5pm–7pm |friday, noon–8pm | saturday, noon–7pm | sunday, noon–5pm Amis Apollonius Rhodius ADDAMS, Jane. Twenty Years at Hull-House. ANTHONY, Susan B. History of Woman Suffrage. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1910 Rochester: Susan B. Anthony, 1886 & 1902 First edition, limited issue, one of 210 copies signed by the First editions, presentation copies of vols. III and IV of the author. The first American woman to be awarded the Nobel “bible” of the women’s suffrage campaign, the only two volumes Peace Prize (in 1931), Addams was the founder of the social published by Anthony herself; inscribed in both by the author on work profession in the US and, among her many roles, she the occasion of her 85th birthday to her cousin Joshua. 2 vols., was vice president of the National-American Woman Suffrage original maroon cloth. An excellent set. Association. Original vellum-backed brown boards. An internally $15,500 [132954] crisp, clean copy. $1,600 [137440] APOLLONIUS RHODIUS. Argonautica. Florence: [Laurentius (Francisci) de Alopa, Venetus,] 1496 AMIS, Kingsley. Lucky Jim A Novel. Editio princeps of the most important Greek epic of the 3rd London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1953 century bce, the definitive telling of the story of Jason and First edition, presentation copy inscribed by Amis, “To John, all the Argonauts and their quest for the Golden Fleece. Late the very best from Kingsley Amis, January 1954”. Only two other 18th-century English green straight-grain morocco gilt, from presentation copies with the inscription dated January 1954 are the library of the English bibliophile and keen student of recorded at auction.