Participatio Journal of the Thomas F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ludere Causa Ludendi QUEEN's PARK FOOTBALL CLUB

QUEEN’S PARK FOOTBALL CLUB 1867 - 2017 150 Years in Scottish Football...... And Beyond Souvenir Brochure July 2017 Ludere Causa Ludendi President’s Foreword Welcome to our 150th Anniversary Brochure. At the meeting which took place on 9th July 1867, by the casting vote of the chairman and first President, Mungo Ritchie, the name of the club to be formed became “Queen’s Park” as opposed to “The Celts,” and Scottish Football was born. Our souvenir brochure can only cover part of our history, our role in developing the game both at home and abroad, our development of the three Hampden Parks, and some of our current achievements not only of our first team, especially the third Hampden Park is still evident as the but of our youth, community and women’s development site continues to evolve and modernise. Most importantly programmes, and our impressive JB McAlpine Pavilion at we continue our commitment to the promotion and Lesser Hampden. development of football in Scotland - and beyond. No. 3 Eglinton Terrace is now part of Victoria Road, but the This brochure is being published in 2017. I hope you enjoy best of our traditions remain part of us 150 years later. We reading it, and here’s to the next 150 years! remain the only amateur club playing in senior football in the UK; we are the oldest club in Scotland; and the vision Alan S. Hutchison of our forebears who developed the first, second and President The Formation of Queen’s Park FC, 9th July 1867 Queen’s Park FC, Scotland’s first association football club, ‘Glasgow, 9th July, 1867. -

Book of Condolences

Book of Condolences Ewan Constable RIP JIM xx Thanks for the best childhood memories and pu;ng Dundee United on the footballing map. Ronnie Paterson Thanks for the memories of my youth. Thoughts are with your family. R I P Thank you for all the memoires, you gave me so much happiness when I was growing up. You were someone I looked up to and admired Those days going along to Tanadice were fantasEc, the best were European nights Aaron Bernard under the floodlights and seeing such great European teams come here usually we seen them off. Then winning the league and cups, I know appreciate what an achievement it was and it was all down to you So thank you, you made a young laddie so happy may you be at peace now and free from that horrible condiEon Started following United around 8 years old (1979) so I grew up through Uniteds glory years never even realised Neil smith where the success came from I just thought it was the norm but it wasn’t unEl I got a bit older that i realised that you were the reason behind it all Thank you RIP MR DUNDEE UNITED � � � � � � � � Michael I was an honour to meet u Jim ur a legend and will always will be rest easy jim xxx� � � � � � � � First of all. My condolences to Mr. McLean's family. I was fortunate enough to see Dundee United win all major trophies And it was all down to your vision of how you wanted to play and the kind of players you wanted for Roger Keane Dundee United. -

PRELIMINARIES (A) Celtic FC Foundation, a Registered Scottish Charitable Incorporated Organisation with the Office of the Scotti

PRELIMINARIES (A) Celtic FC Foundation, a registered Scottish Charitable Incorporated Organisation with the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator (number SC024648) and having its place of business at Celtic Park, Glasgow, G40 3RE (“Celtic FC Foundation”). (B) The following terms and conditions apply to participants in Celtic FC Foundation’s The H.E.L.P Pilgrimage on Monday, 30 May 2016 (the “Event”). Please take time to read these carefully as you are bound by them, on acceptance by Celtic FC Foundation of your entry. (C) All monies will be managed by Celtic FC Foundation and the net proceeds of the monies raised –will be retained by Celtic FC Foundation for delivery of its charitable activities. (D) By registering for the Event, you are agreeing to the following conditions of entry and any instructions given to you by Celtic FC Foundation. 1. Event Details (a) This event features a 17 mile walk encompassing four historical sites (St Mary’s Church, Barrowfield, Jimmy Johnstone Memorial Statue in Viewpark and finally, Celtic Park) and honouring four legendary figures in Celtic FC’s history (Tommy Burns, Jock Stein, Jimmy Johnstone and Brother Walfrid) at each respective venue. (b) The Event will commence at St Mary’s Parish Church, 89 Abercromby Street, Glasgow G40 2DQ (the “Venue”). (c) The Event is scheduled to take place on Monday, 30 May 2016 (the “Event Date”). However, Celtic FC Foundation cannot predict the weather and forecasts can sometimes be unreliable. Therefore, there is no guarantee the Event will take place on that day and an alternative may need to be arranged. -

Glasgow: in a League of Its Own

ESTABLISHED IN 1863 Volume 148, No. 7 March 2011 Glasgow: In a League of Its Own Inside this Issue BY JONATHAN CLEGG Feature Article………….1 English football is dominated by Scottish managers, and from one city in particular Message from our President…................2 GLASGOW, Scotland—There are some 240 overseas players in the English Pre- mier League. They're spread all over the map—35 from France, seven from Senegal, Upcoming Events…….....3 one each from Uruguay, Mali and Greece. By some measures, it's the most cosmopoli- Tartan Ball flyer ………..6 tan league in all of sports. But when it comes to the men prowling the sidelines, some of the very best come from this same cold, industrial city of 600,000 in western Scot- Gifts to the Society: Mem- land. bership Announce- ments…………….....7 Hear ye, Hear Ye: Notice of motion to be voted on by the membership …………………......7 Dunsmuir Scottish Danc- ers flyer…………….8 Dan Reid Memorial Chal- lenge Recital flyer….9 Press Association—Birmingham City manager Alex McLeish, left, shakes hands with Alex Fergu- son of Manchester United. Both men were raised in Glasgow. (Continued on page 4) March 2011 www.saintandrewssociety-sf.org Page 1 A Message from Our President The Saint Andrew's Dear Members and Society Society of San Francisco Friends: 1088 Green Street San Francisco, CA Our February meeting went well. 94133‐3604 (415) 885‐6644 Second VP David McCrossan served Editor: William Jaggers some excellent pizzas and fresh green Email: [email protected] salad, then entertained and informed Membership Meetings: us with a first class presentation on Meetings are held the the ‚Languages of Scotland.‛ He 3rd Monday of the month, at showed some great film clips, too. -

Jock Stein (Hillhouse, Hamilton) Pitch One Pitch Two Pitch Three

Official Weekly Information Sheet Issue Number 37 NEW WEB SITE FORMAT Week Ending 4th – 6th April 08 New Training arrangements until END OF MAY …..Starting this weekend …….. FRIDAY NIGHT Jock Stein (Hillhouse, Hamilton) Pitch One Pitch Two Pitch Three 6.00 pm – 7.00 pm 1998 Navy – R.Gormley We do not have this pitch We do not have this pitch 1998 White – I.Blair 1998 Red – P.Macmillan NO BLADES ALLOWED FRIDAY NIGHT Jock Stein (Hillhouse, Hamilton) Pitch One Pitch Two Pitch Three 7.00 pm – 8.00 pm 1998 Navy – R.Gormley 1998 Navy – R.Gormley Aberdeen 1998’s – 1998 White – I.Blair 1998 White – I.Blair 1998 Red – P.Macmillan 1998 Red – P.Macmillan B.McDonald E.Gibson S.Gauley NO BLADES ALLOWED NO BLADES ALLOWED FRIDAY NIGHT Hamilton Palace (INDOORS and OUTDOORS) Rotation System Week One - INDOORS Week One - OUTDOORS 7.00 pm – 9.00 pm 1999 Navy - S.Walker 1999 White - J.Renwick (Senior) 1998 Yellow - I.Houston ALL SBC Goalies : R.Bullough / J.Matthews / I.Houston FRIDAY NIGHT Hamilton Palace (INDOORS and OUTDOORS) Rotation System Week Two - INDOORS Week Two - OUTDOORS 7.00 pm – 9.00 pm 1999 White - J.Renwick (Senior) 1999 Navy - S.Walker 1998 Yellow - I.Houston ALL SBC Goalies : R.Bullough / J.Matthews / I.Houston SUNDAY MORNING Hamilton Palace (INDOORS) Top Half Bottom Half 10.00 am – Aberdeen 1999’s / 2000’s – B.Mc Donald Aberdeen 1999’s / 2000’s – B.Mc Donald 11.00 noon R.Bullough R.Bullough SUNDAY MORNING Top Half Bottom Half SBC – 2000 ‘Navy’ – SBC - 2000 ‘White’ 11.00 am – 12.00 noon B.Mc Donald / J.Mallin SBC – ‘Development Squad (‘Colts’) 2000 / 2001 R. -

Hampden Park - Scotland’S National Stadium Sunday, 30Th October 2016

Hampden Park - Scotland’s National Stadium Sunday, 30th October 2016 SUPPORTED BY Another great night at Hampden Park The List of Inductees Once again, Scotland’s National Stadium plays host to the Scottish Football Hall of Fame The inaugural Scottish Football Hall of Fame Dinner in 2004 saw twenty greats of the Scottish game Annual Inductees Dinner. In what promises to be another great evening, guests will see inducted in the Hall of Fame. Since then, there have been over seventy additions to this select band. several new inductees into the Hall of Fame. The evening’s proceedings will be followed 2004 2005 2007 BERTIE AULD 2013 ALAN MORTON WILLIE BAULD PAUL LAMBERT ALAN ROUGH by a tribute to one of Scotland’s true footballing greats. WILLIE WOODBURN ALEX McLEISH ERIC CALDOW JIMMY DELANEY MARTIN BUCHAN JIM BAXTER BOBBY LENNOX JIMMY COWAN MAURICE JOHNSTON EDDIE GRAY Since its inauguration in 2004 over 90 greats of our Sir ALEX FERGUSON ALEX JAMES ALAN HANSEN TOMMY DOCHERTY GRAEME SOUNESS national game have been inducted into the Scottish CHARLES CAMPBELL ALLY McCOIST 2010 SCOT SYMON JOHN GREIG Football Hall of Fame. Who will be joining such GEORGE YOUNG ROSE REILLY CRAIG BROWN BOBBY WALKER JOCK STEIN legendary characters as Denis Law, Kenny Dalglish, JIM McLEAN WALTER SMITH ANDY GORAM BILL SHANKLY Rose Reilly - the fi rst woman to be inducted - and JOE JORDAN GORDON STRACHAN PAUL McSTAY 2014 BILLY McNEILL DAVID NAREY international superstars Henrik Larsson and Brian JOHN WHITE EDDIE TURNBULL PETER LORIMER JIMMY McGRORY LAWRIE REILLY TOM ‘Tiny’ WHARTON DAVIE WILSON Laudrup? DANNY McGRAIN WILLIE WADDELL 2008 BOBBY JOHNSTONE CHARLIE NICHOLAS BOBBY MURDOCH JOHN THOMSON BILL BROWN This year promises to be yet another memorable JIMMY JOHNSTONE 2006 BILL STRUTH 2011 McCRAE’S occasion. -

Jock Stein – the Definitive Biography Archie Macpherson - Highdown - ISBN 1-904317-73-1

Books – Jock Stein – The Definitive Biography Archie MacPherson - Highdown - ISBN 1-904317-73-1 Jock Stein might have only held the reins at Elland Road for 44 days (spookily the same length of time as Old Big ‘Ead), but there’s no way I could really exclude this book from those covered on the Mighty Leeds website. You see, this site is about much more than just football and this remarkable club, it also attempts to cover a little bit of the social history of the last 100 years or so, and the 1960’s and 1970’s, when Stein reigned supreme as the peerless manager of Glasgow Celtic, is a rich period indeed for study of people. The Scot was one of a multitude of genuinely great managers around at the time … Busby, Ramsey, Nicholson, Revie (of course), Shankly and even Cloughie, although he came right at the end of the period. Broadcaster Archie MacPherson bravely titled this tome “Jock Stein – The Definitive Biography”, but he certainly came up with the goods with one truly great piece of work about a truly great man. Just to get the Leeds United stuff out of the way first, there are only a couple of pages included on Stein’s time in charge in The Big Man 1978, but it’s all enthralling stuff, and we also get a great insight into the clash between Celtic in Leeds in the European Cup semi finals in 1970: “Stein had great respect for Don Revie, the Leeds manager, as an original thinker in the game, but he did not think Celtic deserved the treatment they received both before and after the match. -

BOBBY BROWN a Life in Football, from Goals to the Dugout

BOBBY BROWN A Life in Football, From Goals to the Dugout Jack Davidson Contents Foreword 9 1. Wembley 1967 11 2 Early Days and Queen’s Park 41 3. Jordanhill College and War; International Debut 59 4. Post War and Queen’s Park 85 5. First Year at Rangers 94 6. Rangers 1947–52 110 7. Final Years as a Player 126 8. St Johnstone Manager 142 9. Scotland Manager – Early Days and World Tour 161 10. The Quest for Mexico 1970 185 11. Final Years as Scotland Manager 214 12 Family Life and Business Career 235 13. Full Time 246 Chapter 1 Wembley 1967 S dream starts to new jobs go, even Carlsberg would have struggled to improve on Bobby Brown’s. Appointed A Scotland team manager only two months earlier, on 11 April 1967 he oversaw his team beating England, then reigning world champions, at Wembley, English football’s impressive and emblematic stadium. It was his first full international in charge and England’s first loss in 20 games. To defeat the world champions, Scotland’s most intense and enduring rivals, in these circumstances was an outstanding achievement, like winning the Grand National on your debut ride or running a four-minute mile in your first race. The date is enshrined in Scottish football history as one of its most memorable days. In fans’ folklore, it was the day when Scotland became ‘unofficial world champions’ by knocking England off their throne – and what could be sweeter for a Scottish fan? As Brown said, in his understated way at the time, ‘It was a fairly daunting task for your first game in charge. -

Celtic Offer the Collector’S Edition the Archives Collection

PRE-RELEASE CELTIC OFFER THE COLLECTOR’S EDITION THE ARCHIVES COLLECTION CELEBRATING THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE 1967 EUROPEAN CUP WIN For a limited time, you have the opportunity to be a part of Celtic’s Official Archives Collection. Simply pre-order yourcopy, upload your photo and your collection will be reserved and your photo will feature in Chapter 10 The Faithful – The Fans. THIS COULD BE YOU! ub Fan Celtic Football Cl FEATURES INCLUDE: • 5 Full size replica Medals • Replica 1967 European Cup Final Programme • Rare never before seen photographs • League Championship Winners Cards • The 1967 Annual Report and Balance Sheet • Jock Stein & Charlie Tully’s 1953 Player Contracts To order your copy, please visit: www.celticiconseries.com CELTIC_A5_Flyer_Pre_Release-6.indd 1 19/10/2016 5:24 pm LIFT OUT MEMORABILIA INSIDE THIS COLLECTION INCLUDES REPLICA CELTIC PLAYERS MEDALS CELTIC FOOTBALL CLUB LEGENDS POSTER – SIZE: 950 X 250 MM ACTUAL SIZE REPRODUCTION 1888/89 Glasgow North-Eastern Celtic Football Club Commemorative Cup Medal Won By Willie Maley Medal In Recognition of winning 4 Trophies in the 1907/08 season. 1967 European Cup Medal THE 1967 ANNUAL REPORT AND BALANCE SHEET 1927 Scottish Cup Medal 1895/96 League Championship Won By James McMenemy Medal Won By William Ferguson 1894/95 CELTIC FOOTBALL GUIDE 1967 EUROPEAN CUP AND FIXTURE BOOKLET FINAL TICKET REPLICA 1967 EUROPEAN CUP JOCK STEIN & CHARLIE TULLY’S THE CELTIC FOOTBALL FINAL PROGRAMME PLAYER CONTRACTS CLUB CHEQUE TO JAMES MCGRORY FOR SERVICES RENDERED 1960 10/10/2016 11:53 am 1967 Euro Final Program-2.indd 1 BE A PART OF ORDER NOW HISTORY IN 3 EASY STEPS ub Fan Celtic Football Cl Photo upload offer available until 30 October 2016. -

Keeping the Legend Alive

KEEPING THE LEGEND ALIVE Word count: 1,473 How a simple design brief with clear objectives helped cement a football stadium’s place in history and breathe new life into an iconic landmark, a brand, a community and a legion of worldwide fans. This is the story of ‘Paradise’. The Celtic Story Celtic Football Club is a professional football club based in the East End of Glasgow. It is one of the oldest brands in the world. Founded in 1887 by Irish emigrant, Brother Walfrid to help alleviate the poverty and desperation of 19th Century East End of Glasgow, Celtic has always been a symbol of “community identity, pride and confidence”. Fast-forward to 2015, and that same sense of pride still lay at the heart of the club’s identity. Brother Walfrid Celtic Park stands in Glasgow’s Parkhead district. Proudly referred to as ‘Paradise’ by Celtic’s vast legion of fans, it has been a feature of Glasgow’s skyline for more than a hundred years. But more than that, it has been an enduring landmark in Glasgow’s history. With a capacity of 60,411, it is the largest Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games. the action. The stadium has a lot to offer Celtic football club stadium in Scotland and second A testament to the stature Celtic Park has fans and sports fans alike; not to mention largest in the UK. It has hosted a wide range amongst the fans and the East End community; providing the venue for recruitment drives of international football matches and sporting it was the natural choice for the ceremony due during WW1 and world-tour concerts from events, including the opening ceremony for the to its layout bringing spectators close to the likes of U2 and The Who. -

SB-4104-October

the www.scottishbanner.com Scottishthethethe North American EditionBanner 37 Years StrongScottish - 1976-2013 BannerA’ Bhratach Albannach ScottishVolumeScottish 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international BannerBanner Scottish newspaper May 2013 41 Years Strong - 1976-2017 www.scottishbanner.com Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 VolumeVolumeVolume 41 36 36 Number Number Number 4 11 11The The The world’s world’s world’s largest largest largest international international international Scottish Scottish newspaper newspaper newspaper May OctoberMay 2013 2013 2017 The Forth Graham Bridges McTavish Crossing into history talks Outlander » Pg 13 » Pg 14 Scotland named The Real as ‘Most beautiful country’ in the world History » Pg 18 Behind the Australia $3.75; North American $3.00; N.Z. $3.95; U.K. £2.00 Outlander Tim Stead-Wood genius ...... » Pg 11 Scottish Halloween Effect Traditions .................................... » Pg 12 » Pg 17 The Law of Innocents ........... » Pg 25 THE SCOTTISH BANNER Scottishthe Volume Banner 41 - Number 4 The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Publisher Valerie Cairney Editor Sean Cairney y EDITORIAL STAFF A spook kiss Jim Stoddart Ron Dempsey, FSA Scot in our group came to breakfast asking MacKenzie and made it his own The National Piping Centre David McVey who had a barking dog, staff quickly and literally brought the character Angus Whitson Lady Fiona MacGregor told us there in fact was no dog at the swinging out of the pages of Diana Marieke McBean David C. Weinczok hotel. However it was a faithful dog Gabaldon’s books to our screens. -

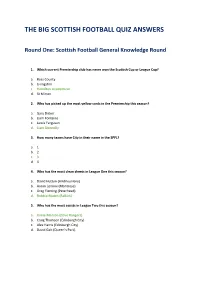

The Big Scottish Football Quiz Answers

THE BIG SCOTTISH FOOTBALL QUIZ ANSWERS Round One: Scottish Football General Knowledge Round 1. Which current Premiership club has never won the Scottish Cup or League Cup? a. Ross County b. Livingston c. Hamilton Academical d. St Mirren 2. Who has picked up the most yellow cards in the Premiership this season? a. Gary Dicker b. Liam Fontaine c. Lewis Ferguson d. Liam Donnelly 3. How many teams have City in their name in the SPFL? a. 1 b. 2 c. 3 d. 4 4. Who has the most clean sheets in League One this season? a. David Hutton (Airdrieonians) b. Aaron Lennox (Montrose) c. Greg Fleming (Peterhead) d. Robbie Mutch (Falkirk) 5. Who has the most assists in League Two this season? a. Jamie Masson (Cove Rangers) b. Craig Thomson (Edinburgh City) c. Alex Harris (Edinburgh City) d. David Galt (Queen’s Park) 6. Celtic hold the record for most consecutive appearances in a league cup final but how many was it? a. 4 b. 7 c. 10 d. 14 7. Who are Glasgow City due to play in their Women’s Champions League Quarter-Final? a. Wolfsburg b. Lyon c. Arsenal d. Barcelona 8. Which team is currently bottom of the Lowland League? a. Vale of Leithen b. Dalbeattie Star c. Edinburgh University d. Gretna 2008 9. Brora Rangers were crowned as winners of the Highland League but who were runners- up? a. Formartine United b. Fraserburgh c. Inverurie Loco Works d. Buckie Thistle 10. When was the last time neither Celtic nor Rangers won the top division in Scotland? a.