Nesting Fork-Tailed Swifts Apus Pacificus in North-Eastern Vietnam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observations of Pale and Rüppell's Fox from the Afar Desert

Dinets et al. Pale and Rüppell’s fox in Ethiopia Copyright © 2015 by the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. ISSN 1478-2677 Research report Observations of pale and Rüppell’s fox from the Afar Desert, Ethiopia Vladimir Dinets1*, Matthias De Beenhouwer2 and Jon Hall3 1 Department of Psychology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996, USA. Email: [email protected] 2 Biology Department, University of Leuven, Kasteelpark Arenberg 31-2435, BE-3001 Heverlee, Belgium. 3 www.mammalwatching.com, 450 West 42nd St., New York, New York 10036, USA. * Correspondence author Keywords: Africa, Canidae, distribution, Vulpes pallida, Vulpes rueppellii. Abstract Multiple sight records of pale and Rüppell’s foxes from northwestern and southern areas of the Afar De- sert in Ethiopia extend the ranges of both species in the region. We report these sightings and discuss their possible implications for the species’ biogeography. Introduction 2013 during a mammalogical expedition. Foxes were found opportu- nistically during travel on foot or by vehicle, as specified below. All coordinates and elevations were determined post hoc from Google The Afar Desert (hereafter Afar), alternatively known as the Afar Tri- Earth. Distances were estimated visually. angle, Danakil Depression, or Danakil Desert, is a large arid area span- ning Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti and Somaliland (Mengisteab 2013). Its fauna remains poorly known, as exemplified by the fact that the first Results possible record of Canis lupus dates back only to 2004 (Tiwari and Sillero-Zubiri 2004; note that the identification in this case is still On 14 May 2007, JH saw a fox in degraded desert near the town of uncertain). -

Predicting the Responses of Native Birds to Transoceanic Invasions by Avian Brood Parasites

J. Field Ornithol. 86(3):244–251, 2015 DOI: 10.1111/jofo.12111 Predicting the responses of native birds to transoceanic invasions by avian brood parasites Vladimir Dinets,1,5 Peter Samaˇs,2 Rebecca Croston,3,4 Toma´ˇsGrim,2 and Mark E. Hauber3 1Department of Psychology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996, USA 2Department of Zoology and Laboratory of Ornithology, Palacky´ University, Olomouc 77146, Czech Republic 3Department of Psychology, Hunter College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York, New York, New York 10065, USA 4Department of Biology, University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada 89557, USA Received 19 April 2015; accepted 6 June 2015 ABSTRACT. Three species of brood parasites are increasingly being recorded as transoceanic vagrants in the Northern Hemisphere, including two Cuculus cuckoos from Asia to North America and a Molothrus cowbird from North America to Eurasia. Vagrancy patterns suggest that their establishment on new continents is feasible, possibly as a consequence of recent range increases in response to a warming climate. The impacts of invasive brood parasites are predicted to differ between continents because many host species of cowbirds in North America lack egg rejection defenses against native and presumably also against invasive parasites, whereas many hosts of Eurasian cuckoos frequently reject non-mimetic, and even some mimetic, parasitic eggs from their nests. During the 2014 breeding season, we tested the responses of native egg-rejecter songbirds to model eggs matching in size and color the eggs of two potentially invasive brood parasites. American Robins (Turdus migratorius)areamongthe few rejecters of the eggs of Brown-headed Cowbirds (M. -

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species 02 05 Restore Canada Jay as the English name of Perisoreus canadensis 03 13 Recognize two genera in Stercorariidae 04 15 Split Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus) into two species 05 19 Split Pseudobulweria from Pterodroma 06 25 Add Tadorna tadorna (Common Shelduck) to the Checklist 07 27 Add three species to the U.S. list 08 29 Change the English names of the two species of Gallinula that occur in our area 09 32 Change the English name of Leistes militaris to Red-breasted Meadowlark 10 35 Revise generic assignments of woodpeckers of the genus Picoides 11 39 Split the storm-petrels (Hydrobatidae) into two families 1 2018-B-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 280 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species Effect on NACC: This proposal would change the species circumscription of Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus by splitting it into four species. The form that occurs in the NACC area is nominate pacificus, so the current species account would remain unchanged except for the distributional statement and notes. Background: The Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus was until recently (e.g., Chantler 1999, 2000) considered to consist of four subspecies: pacificus, kanoi, cooki, and leuconyx. Nominate pacificus is highly migratory, breeding from Siberia south to northern China and Japan, and wintering in Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The other subspecies are either residents or short distance migrants: kanoi, which breeds from Taiwan west to SE Tibet and appears to winter as far south as southeast Asia. -

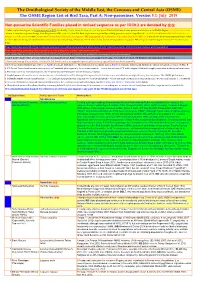

ORL 5.1 Non-Passerines Final Draft01a.Xlsx

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part A: Non-passerines. Version 5.1: July 2019 Non-passerine Scientific Families placed in revised sequence as per IOC9.2 are denoted by ֍֍ A fuller explanation is given in Explanation of the ORL, but briefly, Bright green shading of a row (eg Syrian Ostrich) indicates former presence of a taxon in the OSME Region. Light gold shading in column A indicates sequence change from the previous ORL issue. For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates added information since the previous ORL version or the Conservation Threat Status (Critically Endangered = CE, Endangered = E, Vulnerable = V and Data Deficient = DD only). Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative convenience and may change. Please do not cite them in any formal correspondence or papers. NB: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text indicate recent or data-driven major conservation concerns. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. English names shaded thus are taxa on BirdLife Tracking Database, http://seabirdtracking.org/mapper/index.php. Nos tracked are small. NB BirdLife still lump many seabird taxa. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. -

Aggregated Occurrence Records of the Invasive Alien Striped Field Mouse (Apodemus Agrarius Pall.) in the Former USSR

Biodiversity Data Journal 9: e69159 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.9.e69159 Data Paper Aggregated occurrence records of the invasive alien striped field mouse (Apodemus agrarius Pall.) in the former USSR Lyudmila A Khlyap‡, Vladimir Dinets §,|, Andrey A Warshavsky‡‡, Fedor A Osipov , Natalia N Dergunova‡, Varos G Petrosyan‡ ‡ A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia § University of Tennessee, Knoxville, United States of America | Kean University, Union, United States of America Corresponding author: Varos G Petrosyan ([email protected]) Academic editor: Alexander E Balakirev Received: 26 May 2021 | Accepted: 17 Jun 2021 | Published: 22 Jun 2021 Citation: Khlyap LA, Dinets V, Warshavsky AA, Osipov FA, Dergunova NN, Petrosyan VG (2021) Aggregated occurrence records of the invasive alien striped field mouse (Apodemus agrarius Pall.) in the former USSR. Biodiversity Data Journal 9: e69159. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.9.e69159 Abstract Background Open access to occurrence records of the most dangerous invasive species in a standardised format have important potential applications for ecological research and management, including the assessment of invasion risks, formulation of preventative and management plans in the context of global climate and land use changes in the short and long perspective. The striped field mouse (Apodemus agrarius Pallas, 1771) is a common species in the temperate latitudes of the Palaearctic. Due to land use and global climate changes, several waves of expansion of the range of this species have been observed or inferred. By intrusion into new regions, the striped field mouse has become an alien species there. Apodemus agrarius causes significant harm to agriculture and is one of the most important pests of grain crops. -

Red List of Bangladesh 2015

Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary Chief National Technical Expert Mohammad Ali Reza Khan Technical Coordinator Mohammad Shahad Mahabub Chowdhury IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature Bangladesh Country Office 2015 i The designation of geographical entitles in this book and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature concerning the legal status of any country, territory, administration, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The biodiversity database and views expressed in this publication are not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, Bangladesh Forest Department and The World Bank. This publication has been made possible because of the funding received from The World Bank through Bangladesh Forest Department to implement the subproject entitled ‘Updating Species Red List of Bangladesh’ under the ‘Strengthening Regional Cooperation for Wildlife Protection (SRCWP)’ Project. Published by: IUCN Bangladesh Country Office Copyright: © 2015 Bangladesh Forest Department and IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holders, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holders. Citation: Of this volume IUCN Bangladesh. 2015. Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary. IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh Country Office, Dhaka, Bangladesh, pp. xvi+122. ISBN: 978-984-34-0733-7 Publication Assistant: Sheikh Asaduzzaman Design and Printed by: Progressive Printers Pvt. -

Appendix 12.1 Literature Review

E xpansion of Hong Kong International Airport into a Three-Runway System Environmental Impact Assessment Report Appendix 12.1 Literature Review Literature Review 1 Background 1.1 The purpose of the literature review is to identify existing information on the terrestrial habitats and species present within the study area in order to identify any information gaps and take into account such information gaps in the design of terrestrial ecological surveys. A series of materials, including relevant EIA studies, academic research papers, results of ecological research or monitoring done by government authorities such as the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department (AFCD) or non-government organisations, have been reviewed to gather relevant data on the terrestrial flora and fauna species present in the study area. 1.2 Relevant EIA reports and studies that provide a considerable amount of information on the terrestrial ecology of North Lantau from Sham Wat to Tai Ho Wan and Chek Lap Kok have been reviewed. The EIA reports and studies that have been reviewed include: Hong Kong - Zhuhai - Macao Bridge: Hong Kong Boundary Crossing Facilities and Hong Kong Link Road Final 9 Months Ecological Baseline Survey (Mouchel, 2004); Hong Kong - Zhuhai - Macao Bridge: Hong Kong Link Road Verification Survey of Ecological Baseline Final Report (Asia Ecological Consultants Ltd, 2009); Tuen Mun - Chek Lap Kok Link (TM-CLKL) - Investigation Final EIA Report (AECOM, 2009); Hong Kong - Zhuhai - Macao Bridge: Hong Kong Boundary Crossing Facilities (HKBCF) -

Proceedings 13 Promo.Pdf

FRONTISPIECE. Gary Krapu, Research Wildlife Biologist Emeritus, USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, received the L. H. WALKINSHAW CRANE CONSERVATION AWARD in recognition of his career-long work to better understand the needs of sandhill cranes in the Platte River ecosystem; initiate a comprehensive, long-term research program to guide conservation and management of the Mid-continental Population of sandhill cranes; and for collaborative research efforts with biologists of other nations to guide international conservation of cranes. The Award was presented by Jane Austin, President of the North American Crane Working Group, on 17 April 2014. Gary received his M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in Animal Ecology from Iowa State University. He was employed as a Research Wildlife Biologist at Northern Prairie under the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and U.S. Geological Survey from 1968 until his retirement in 2011 and in emeritus status thereafter. While at Northern Prairie, he also conducted studies on waterfowl, including wetland habitat requirements, role of stored nutrients in waterfowl reproduction, brood habitat use and factors influencing duckling survival, waterfowl nutrition, and staging ecology of white-fronted geese. He continues to conduct research on sandhill cranes at Northern Prairie, primarily studying population dynamics of the Mid-continent Population and the geographic distribution and ecology of sandhill cranes breeding in Russia and western Alaska. (Photo by Glenn Olsen) Front cover: Whooping crane family at nest, Jefferson Davis Parish, Louisiana, April 2016, by Eva Szyszkoski, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. Back cover: Scenes from the Thirteenth Workshop in Lafayette, Louisiana, by Barry Hartup, Glenn Olsen, Tommy Michot, Eva Szyszkoski, Richard Urbanek, and Sara Zimorski. -

Digitalcommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Proceedings of the North American Crane North American Crane Working Group Workshop

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Proceedings of the North American Crane North American Crane Working Group Workshop 2016 Frontmatter for PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTEENTH NORTH AMERICAN CRANE WORKSHOP David A. Aborn Richard Urbanek Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nacwgproc Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Ornithology Commons, Population Biology Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the North American Crane Working Group at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the North American Crane Workshop by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTEENTH NORTH AMERICAN CRANE WORKSHOP 14-17 April 2014 Lafayette, Louisiana FRONTISPIECE. Gary Krapu, Research Wildlife Biologist Emeritus, USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, received the L. H. WALKINSHAW CRANE CONSERVATION AWARD in recognition of his career-long work to better understand the needs of sandhill cranes in the Platte River ecosystem; initiate a comprehensive, long-term research program to guide conservation and management of the Mid-continental Population of sandhill cranes; and for collaborative research efforts with biologists of other nations to guide international conservation of cranes. The Award was presented by Jane Austin, President of the North American Crane Working Group, on 17 April 2014. Gary received his M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in Animal Ecology from Iowa State University. He was employed as a Research Wildlife Biologist at Northern Prairie under the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and U.S. -

Checklist of the Birds of Western Australia R.E

Checklist of the Birds of Western Australia R.E. Johnstone and J.C. Darnell Western Australian Museum, Perth, Western Australia 6000 April 2016 ____________________________________ The area covered by this Western Australian Checklist includes the seas and islands of the adjacent continental shelf, including Ashmore Reef. Refer to a separate Checklist for Christmas and Cocos (Keeling) Islands. Criterion for inclusion of a species or subspecies on the list is, in most cases, supported by tangible evidence i.e. a museum specimen, an archived or published photograph or detailed description, video tape or sound recording. Amendments to the previous Checklist have been carried out with reference to both global and regional publications/checklists. The prime reference material for global coverage has been the International Ornithological Committee (IOC) World Bird List, The Clements Checklist of Birds of the World, the Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volume, 1 (Lynx Edicions, Barcelona), A Checklist of the Birds of Britain, 8th edition, the Checklist of North American Birds and, for regional coverage, Zoological Catalogue of Australia volume 37.2 (Columbidae to Coraciidae), The Directory of Australian Birds, Passerines and the Working List of Australian Birds (Birdlife Australia). The advent of molecular investigation into avian taxonomy has required, and still requires, extensive and ongoing revision at all levels – family, generic and specific. This revision to the ‘Checklist of the Birds of Western Australia’ is a collation of the most recent information/research emanating from such studies, together with the inclusion of newly recorded species. As a result of the constant stream of publication of new research in many scientific journals, delays of its incorporation into the prime sources listed above, together with the fact that these are upgraded/re-issued at differing intervals and that their authors may hold varying opinions, these prime references, do on occasion differ. -

Ebird Field Checklist

Parrots, Parakeets, and Allies Vultures, Hawks, and Allies Australian King-Parrot Black-shouldered Kite Swift Parrot Little Eagle Crimson Rosella Wedge-tailed Eagle Eastern Rosella Swamp Harrier Red-rumped Parrot Spotted Harrier 191 species (+4 other taxa) Musk Lorikeet Brown Goshawk Year-round, All Years Little Lorikeet Collared Sparrowhawk Date: Purple-crowned Lorikeet Black Kite Start Time: Whistling Kite Duration: Grouse, Quail, and Allies White-bellied Sea-Eagle Distance: Brown Quail Party Size: Stubble Quail Bee-eaters, Rollers, and Allies Rainbow Bee-eater Waterfowl Loons and Grebes Dollarbird Plumed Whistling-Duck Australasian Grebe Greylag Goose (Domestic type) Hoary-headed Grebe Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers Freckled Duck Great Crested Grebe Silver Gull Black Swan Gull-billed Tern Australian Shelduck Cormorants and Anhingas Caspian Tern Australian Wood Duck Little Pied Cormorant White-winged Black Tern Australasian Shoveler Great Cormorant Whiskered Tern Pacific Black Duck Little Black Cormorant Grey Teal Pied Cormorant Pigeons and Doves Chestnut Teal Australasian Darter Rock Dove Pink-eared Duck Spotted Dove Hardhead Pelicans Common Bronzewing Blue-billed Duck Australian Pelican Crested Pigeon Musk Duck Peaceful Dove Herons, Ibis, and Allies Shorebirds White-necked Heron Cuckoos Pied Stilt Great Egret Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo Red-necked Avocet Intermediate Egret Black-eared Cuckoo Pacific Golden-Plover White-faced Heron Shining Bronze-Cuckoo Masked Lapwing Cattle -

Pacific Swift: New to the Western Palearctic

British Birds VOLUME 83 NUMBER 2 FEBRUARY1990 Pacific Swift: new to the Western Palearctic Mike Parker n 19th June 1981, R. Waiden was on the deck of the Shell BT gas- Oplatform on the Leman Bank at 53°06'N 02°12'E, about 45 km off Happisburgh, Norfolk, when a bird attempted to land on his Shoulder. It then flew past him and clung to a wall on the rig. He caught the exhausted migrant at about 13.30 GMT, and sent it ashore on the next helicopter flight for release, as caring rig-workers often do. At 19.30 GMT, the helicopter arrived at Beccles Heliport in Suffolk, where I work. Mrs S. Irons rang me from the passenger terminal to say she had just been handed a swift which seemed unable to fly; knowing I was a birdwatcher, she asked if I could help. To my astonishment, the bird lying on her cardigan was indeed a swift, but with a startling white rump and all the [Brit. Sink 83: 43-46, February 1990] 43 44 Pacific Swift: new to the Western Palearctic Hi Pacific Swift Apus pacificus, Suffolk, June 1981 (Gary Davies) upper body feathers pale-tipped, giving a very scaly appearance. My colleagues were somewhat startled when I reacted by running around closing all the windows. At first, I assumed that it was one of the two European white-rumped species—Little Swift Apus qffinis or White-rumped Swift A. caffer. This bird, however, had an obvious forked tail, so I discounted Little Swift. I phoned C.