Towers of Power: an Empirical Analysis of Toronto's Central

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

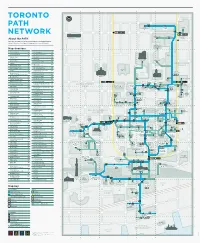

PATH Underground Walkway

PATH Marker Signs ranging from Index T V free-standing outdoor A I The Fairmont Royal York Hotel VIA Rail Canada H-19 pylons to door decals Adelaide Place G-12 InterContinental Toronto Centre H-18 Victory Building (80 Richmond 1 Adelaide East N-12 Hotel D-19 The Hudson’s Bay Company L-10 St. West) I-10 identify entrances 11 Adelaide West L-12 The Lanes I-11 W to the walkway. 105 Adelaide West I-13 K The Ritz-Carlton Hotel C-16 WaterPark Place J-22 130 Adelaide West H-12 1 King West M-15 Thomson Building J-10 95 Wellington West H-16 Air Canada Centre J-20 4 King West M-14 Toronto Coach Terminal J-5 100 Wellington West (Canadian In many elevators there is Allen Lambert Galleria 11 King West M-15 Toronto-Dominion Bank Pavilion Pacific Tower) H-16 a small PATH logo (Brookfield Place) L-17 130 King West H-14 J-14 200 Wellington West C-16 Atrium on Bay L-5 145 King West F-14 Toronto-Dominion Bank Tower mounted beside the Aura M-2 200 King West E-14 I-16 Y button for the floor 225 King West C-14 Toronto-Dominion Centre J-15 Yonge-Dundas Square N-6 B King Subway Station N-14 TD Canada Trust Tower K-18 Yonge Richmond Centre N-10 leading to the walkway. Bank of Nova Scotia K-13 TD North Tower I-14 100 Yonge M-13 Bay Adelaide Centre K-12 L TD South Tower I-16 104 Yonge M-13 Bay East Teamway K-19 25 Lower Simcoe E-20 TD West Tower (100 Wellington 110 Yonge M-12 Next Destination 10-20 Bay J-22 West) H-16 444 Yonge M-2 PATH directional signs tell 220 Bay J-16 M 25 York H-19 390 Bay (Munich Re Centre) Maple Leaf Square H-20 U 150 York G-12 you which building you’re You are in: J-10 MetroCentre B-14 Union Station J-18 York Centre (16 York St.) G-20 in and the next building Hudson’s Bay Company 777 Bay K-1 Metro Hall B-15 Union Subway Station J-18 York East Teamway H-19 Bay Wellington Tower K-16 Metro Toronto Convention Centre you’ll be entering. -

Kanada Osten

ADAC Reiseführer JETZT mit Maxi Klappkarten- Kanada Osten Nationalparks • Fischerdörfer • Outdoor Activities Museen • Shopping Malls • Hotels • Restaurants ADAC Reiseführer Kanada Osten 1DWLRQDOSDUNVʬ)LVFKHUG¸UIHUʬ2XWGRRU$FWLYLWLHV 0XVHHQʬ6KRSSLQJ0DOOVʬ+RWHOVʬ5HVWDXUDQWV Die Top Tipps I¾KUHQ6LH]XGHQ+LJKOLJKWV von Andreas Srenk Intro Kanada Impressionen 6 Grandiose Natur und verlockende Metropolen Geschichte, Kunst, Kultur im Überblick 12 Natives und Inuit, Franzosen und Engländer, Architektur, Film und Literatur in und aus Kanada Unterwegs Ontario – das kraftvolle Herz Kanadas 18 1 Toronto 19 Downtown 21 Chinatown und Kensington Market 26 Rund um Yorkville 26 Toronto Islands 29 Vaughan Mills 29 Kleinburg 29 2 Niagara Falls 30 3 Niagara-on-the-Lake 34 4 Kitchener/Waterloo 34 5 Windsor 35 Point Pelee National Park 36 6 Kingston 36 7 Upper Canada Village 39 8 Ottawa 40 Parliament Hill und Wellington Street 40 Vom Canal Rideau zum Sussex Drive 43 Am Ufer des Ottawa River und rund ums Zentrum 46 Gatineau Park 47 9 Algonquin Provincial Park 49 10 Georgian Bay 50 Fathom Five National Marine Park 51 Manitoulin Island 51 Georgian Bay Islands National Park 51 Killarney Provincial Park 51 11 Sudbury 52 12 Thunder Bay 52 13 Cochrane 53 Moosonee 53 Québec – die launische Diva 54 14 Montréal 55 Vieux Montréal 57 Centre Ville 61 Quartier Latin und Mont Royal 64 Olympiagelände 67 Île Sainte-Hélène und Île Notre-Dame 67 Laurentides 68 15 Trois-Rivières 69 16 Québec City 70 Vieux Québec – Haute-Ville 73 Vieux Québec – Basse-Ville 74 Außerhalb der Stadtmauern 76 Île d’Orléans 76 Montmorency Falls 77 17 Tadoussac 79 18 Gaspésie 79 New Brunswick – die unbe kannte Provinz mit grandioser Natur 82 19 Fredericton 83 Kings Landing 84 Miramichi River 84 20 Saint John 85 21 St. -

PATH Network

A B C D E F G Ryerson TORONTO University 1 1 PATH Toronto Atrium 10 Dundas Coach Terminal on Bay East DUNDAS ST W St Patrick DUNDAS ST W NETWORK Dundas Ted Rogers School One Dundas Art Gallery of Ontario of Management West Yonge-Dundas About the PATH Square 2 2 Welcome to the PATH — Toronto’s Downtown Underground Pedestrian Walkway UNIVERSITY AVE linking 30 kilometres of underground shopping, services and entertainment ST PATRICK ST BEVERLEY ST BEVERLEY ST M M c c CAUL ST CAUL ST Toronto Marriott Downtown Eaton VICTORIA ST Centre YONGE ST BAY ST Map directory BAY ST A 11 Adelaide West F6 One King West G7 130 Adelaide West D5 One Queen Street East G4 Eaton Tower Adelaide Place C5 One York D11 150 York St P PwC Tower D10 3 Toronto 3 Atrium on Bay F1 City Hall 483 Bay Street Q 2 Queen Street East G4 B 222 Bay E7 R RBC Centre B8 DOWNTOWN Bay Adelaide Centre F5 155 Wellington St W YONGE Bay Wellington Tower F8 RBC WaterPark Place E11 Osgoode UNIVERSITY AVE 483 Bay Richmond-Adelaide Centre D5 UNIVERSITY AVE Hall F3 BAY ST 120 Adelaide St W BAY ST CF Toronto Bremner Tower / C10 Nathan Eaton Centre Southcore Financial Centre (SFC) 85 Richmond West E5 Phillips Canada Life Square Brookfield Place F8 111 Richmond West D5 Building 4 Old City Hall 4 2 Queen Street East C Cadillac Fairview Tower F4 Roy Thomson Hall B7 Cadillac Fairview Royal Bank Building F6 Tower CBC Broadcast Centre A8 QUEEN ST W Osgoode QUEEN ST W Thomson Queen Building Simpson Tower CF Toronto Eaton Centre F4 Royal Bank Plaza North Tower E8 QUEEN STREET One Queen 200 Bay St Four -

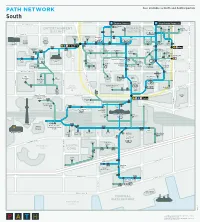

Path Network

PATH NETWORK Also available as North and Central posters South Sheraton Centre 3min Yonge-Dundas Square 10min ADELAIDE ST W ADELAIDE ST W Northbridge 100 – 110 VICTORIA ST Place Yonge 11 Dynamic ENTERTAINMENT FINANCIAL Adelaide Funds Tower DISTRICT DISTRICT Scotia Plaza West PEARL ST 200 King 150 King West West Exchange Tower First Canadian Place The Bank Princess Royal of Nova of Wales Alexandra Scotia TIFF Bell Theatre Theatre Royal Bank 4 King Lightbox Building West St Andrew KING ST W KING ST W King 225 King Commerce Commerce West 145 King 121 King TD North Court Court North West West Tower TD Bank West Collins Pavilion Barrow Place EMILY ST EMILY ST One King West Metro Toronto-Dominion Centre Roy Thomson YORK ST COLBORNE ST Metro Hall Centre Design Commerce Court Hall 55 Exchange SCOTTSCOTT STST University TD West Toronto-Dominion 200 Tower Bank Tower Accessible Wellington route through 222 Bay Commerce Level -1 West 70 York Court South WELLINGTON ST W WELLINGTON ST W Bay WELLINGTON ST E Wellington UNIVERSITY AVE Tower CBC North Brookfield The 95 Wellington SIMCOESIMCOE STST Broadcast RBC Tower BAY ST Place JOHN ST JOHN ST Centre Ritz-Carlton Centre West TD South Toronto Tower Royal Bank Plaza 160 Front Fairmont Royal York Street West TD Canada Hockey Hall FRONT ST E under construction Trust Tower South of Fame Simcoe Tower Place Metro Toronto FRONT ST W Meridian Convention Centre YONGE ST Hall North Citigroup Union Place InterContinental Toronto Centre Great Hotel Hall UP Express Visitor THE ESPLANADE SKYWALK Information Centre York -

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation CANADA HOUSING

Offering Circular Dated February 18, 2016 C$2,000,000,000 Aggregate Principal Amount 2.250% Canada Mortgage Bonds™, Series 70, to mature December 15, 2025 Fully Guaranteed as to Principal and Interest by Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (An agent of Her Majesty in right of Canada) Issued by CANADA HOUSING TRUST™ NO. 1 ISSUE PRICE: 103.152% (Plus accrued interest from December 15, 2015 to yield at date of issue about 1.896%) The bonds offered hereby (the “Bonds”) are 2.250% Canada Mortgage Bonds™, Series 70, to mature December 15, 2025, of Canada Housing Trust™ No. 1 (the “Issuer”), a trust established under the laws of the province of Ontario, Canada pursuant to a declaration of trust dated April 9, 2001, as amended, made by its trustee CIBC Mellon Trust Company, and are fully guaranteed as to timely payment of principal and interest by Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (“CMHC”orthe “Guarantor”), as agent of Her Majesty in right of Canada (see “Description of the Bond Indenture and the Bonds – CMHC Guarantee”). The Issuer is authorized to issue Bonds in one or more series and on one or more issue dates pursuant to the Bond Indenture (as defined below). The Bonds are not redeemable prior to maturity (see “Description of the Bond Indenture and the Bonds – Maturity”). The Bonds bear interest at the rate of 2.250% per annum, mature on December 15, 2025 and will be issued in the form of a fully registered global certificate or in fully registered uncertificated form (in either of the foregoing forms, the “Global Bond”) in the name of CDS & CO. -

SERVICE LIST BORDEN LADNER GERVAIS LLP Scotia Plaza, 40 King Street West Toronto, on M5H 3Y4 Edmond EB Lamek

1 SERVICE LIST BORDEN LADNER GERVAIS LLP GOODMANS LLP Scotia Plaza, 40 King Street West Bay Adelaide Centre Toronto, ON M5H 3Y4 333 Bay Street, Suite 3400 Toronto, ON M5H 2S7 Edmond E.B. Lamek Tel: 416-367-6311 Joe Latham Email: [email protected] Tel: 416-597-4211 Email: [email protected] Kyle B. Plunkett Tel: 416-367-6314 Jason Wadden Email: [email protected] Tel: 416.597.5165 Email: [email protected] Lawyers for Urbancorp CCAA Entities Lawyers for Reznik, Paz, Nevo Trustees Ltd., in its capacity as the Trustee for the Debenture Holders (Series A) and Adv. Gus Gissin, in his capacity as the Israeli Functionary of Urbancorp. Inc. THE FULLER LANDAU GROUP INC. GOLDMAN SLOAN NASH & HABER 151 Bloor Street West, 12th Floor (GSNH) LLP Toronto, ON M5S 1S4 480 University Avenue, Suite 1600 Toronto, ON M5G 1V2 Gary Abrahamson Tel: 416-645-6524 Mario Forte Fax: 416-645-6501 Tel: 416-597-6477 Email [email protected] Fax: 416-597-3370 Email: [email protected] Adam Erlich Tel: 416-645-6560 Robert J. Drake Fax: 416-645-6501 Tel: 416-597-5014 Email: [email protected] Fax: 416-597-3370 Email: [email protected] The Proposal Trustee Lawyers for the Proposal Trustee 2 BENNETT JONES LLP CHAITONS LLP 3400 One First Canadian Place 5000 Yonge Street, 10th Floor P.O. Box 130 Toronto, ON M2N 7E9 Toronto, ON M5X 1A4 Harvey Chaiton S. Richard Orzy Tel: 416-218-1129 Tel: 416-777-5737 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Lawyers for BMO Raj Sahni Tel: 416-863-1200 Email: [email protected] Jonathan G. -

SERVICE LIST TO: OSLER, HOSKIN & HARCOURT LLP PO Box 50 1 First Canadian Place Toronto, on M5X 1B8 John Macdonald

SERVICE LIST TO: OSLER, HOSKIN & HARCOURT LLP P.O. Box 50 1 First Canadian Place Toronto, ON M5X 1B8 John MacDonald Tel: 416-862-5672 E-mail:[email protected] Mary Paterson Tel: 416-862-4924 E-mail:[email protected] Fax: 416-862-6666 Lawyers for the applicant, Thomas Cook Canada, Ltd. AND TO: THORNTONGROUTFINNIGAN LLP Suite 3200, Canadian Pacific Tower 100 Wellington St. West, P.O. Box 329 Toronto-Dominion Centre Toronto, ON M5K 1K7 Robert I. Thornton Tel: 416-304-0560 E-mail:[email protected] Seema Aggarwal Tel: 416-304-0603 E-mail:[email protected] Fax: 416-304-1313 Lawyers for Skyservice Airlines Inc. AND TO: BENNETT JONES LLP One First Canadian Place Suite 3400 100 King Street West, P.O. Box 130 Toronto, ON M5K 1A4 Mark S. Laugesen Tel: 416-777-4802 McCarthy Tétrault LLP DOCS #1177015 v. 1 Fax: 416-863-1716 E-mail:[email protected] Lawyers for Gibralt Capital Corporation AND TO: BLAKE, CASSEL & GRAYDON LLP 199 Bay Street Suite 2800, Commerce Court West Toronto ON M5L 1A9 Linc Rogers Tel: 416-863-4168 E-mail: [email protected] Steven J. Weisz Tel: 416-863-2616 E-mail:[email protected] Christopher Burr Tel: 416-863-3301 E-mail:[email protected] Fax: 416-863-2653 Lawyers for Sunwing Tours Inc. and Thomson Airways Limited AND TO: BLAKE, CASSEL & GRAYDON LLP 199 Bay Street Suite 2800, Commerce Court West Toronto ON M5L 1A9 Pamela L. J. Huff Tel: 416-863-2858 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 416-863-2653 Lawyers for C.I.T. -

Hi-Rise Capital Ltd. and Adelaide Street Lofts Inc

MILLER THOMSON LLP T 416.595.8500 MILLER THOMSON SCOTIA PLAZA F 416.595.8695 40 KING STREET WEST, SUITE 5800 AVOCATS | LAWYERS P.O. 60X1011 TORONTO, ON M5H 3S1 CANADA MILLERTHOMSON.COM March 22, 2019 Dear Investors of Hi-Rise Capital Ltd: Re: HI-RISE CAPITAL LTD. AND ADELAIDE STREET LOFTS INC. Pursuant to the Order of the Honourable Mr. Justice Hainey of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice (Commercial List) (the “Court”) dated March 21, 2019 (the “Order") Miller Thomson LLP (“Representative Counsel”) was appointed to represent all individuals and/or entities (“Investors”) that hold an interest in a syndicated mortgage (“SMI”), administered by Hi-Rise Capital Ltd. (“Hi-Rise”), in respect of the property municipally known as 263 Adelaide Street West, Toronto, Ontario (the “Project") and the proposed development known as the “Adelaide Street Lofts”. A copy of the Order, and other information related to this proceeding, is posted on Representative Counsel’s website at the following URL address (the “Website”): http://www.millerthomson.com/en/hirise. All capitalized terms not otherwise defined herein shall have the same meaning ascribed to them in the Order. You are receiving this letter and enclosures because you are an Investor. Please find enclosed the following: 1. Opt-Out Notice: If you do not wish to be represented by Representative Counsel, you may complete and submit this form to Representative Counsel. 2. Call for Official Committee Applications: If you are interested in serving as a Member of the Official Committee, please follow the instructions on this letter and submit your application to Representative Counsel. -

Download the Toronto PATH Map

Whatever your destination... ...PATH signs lead the way. On the PATH Map Squares represent buildings. M The Green Line represents links between and through buildings. Colours represent the four points of the compass – Toronto’s north (blue), south (red), east (yellow), and west (orange). Downtown Walkway H represents hotel. C represents cultural building. S represents sports venue. represents tourist attraction Adelaide Place F-9, G-9 MetLife Place M-11 11 Adelaide St. West L-10 MetroCentre B-12 1 Adelaide St. East N-10 Metro Hall B-12 PATH Marker Welcome to PATH – 105 Adelaide St. West I-10 Metro Toronto Convention Centre B-16, C-18 Signs ranging from 130 Adelaide St. West H-9 Munich Re Centre (390 Bay Street) J-7 Toronto’s Downtown Walkway Air Canada Centre J-17 free-standing outdoor pylons linking 27 kilometres of under- Allen Lambert Galleria One Dundas West M-3 to door decals identify entrances (Brookfield Place) L-15 One Queen Street East N-7 ground shopping, services and Atrium on Bay K-2 Osgoode Subway Station E-6 to the walkway. entertainment Bank of Nova Scotia K-11 Parking, City Hall I-6 220 Bay J-13 Parking, University Avenue F-15 In many elevators there is 390 Bay (Munich Re Centre) J-7 Plaza at Sheraton Centre, The H-7 Bay Adelaide Centre L-8 a small PATH logo mounted Bay East Teamway K-16 1 Queen Street East N-7 beside the button for the floor Bay Wellington Tower K-14 2 Queen Street East N-6 Bay West Teamway J-16 Queen Subway Station N-6 leading to the walkway. -

Towers of Power

JONATHAN KITCHEN Towers of Power An empirical analysis of Toronto’s Central Business District Over the past sixty years, Toronto’s Central Business District (CBD) has become home to an ever-increasing densification of corporate office towers. Accessibility, control, power, and securitization of property has developed through the post- industrial evolution of the built environment, resulting in the exclusion of some individuals. This paper, through theoretical analysis and empirical data collection, argues that unequal access to privatized public spaces within the CBD’s office towers, outdoor plazas, and the underground PATH system reinforces class distinction and capitalist hegemony. The qualitative empirical data used within this paper were collected through observational site visits of twelve corporate office towers and plazas in Toronto’s CBD, as well as the PATH system. Through the analysis of these spaces, this paper concludes that the built environment of the CBD serves only the needs of the dominant capitalist and middle/upper-middle classes. The class distinctions and capitalist hegemony written into these built environments are reinforced through social, cultural, and physical controls of space. On a larger scale, the spatial exclusion of marginalized individuals within the urban environment speaks to a greater social and spatial inequality within the city, suggesting the need to re-evaluate systems of social, economic, and political power. INTRODUCTION The Central Business District (CBD) in downtown Toronto (see Appendix) is one of the oldest areas in the city and yet has had some of the most dramatic changes. It was first developed in 1797 as a residential zone, but by 1850 manufacturing industries had taken over and displaced many of the homes. -

220 Bay Street

Prime retail for lease – one of Canada’s busiest intersections 220 Bay Street Tim J.A. Hooton Mike Brouwer Principal, Sales Representative Vice President, Sales Representative O: 416.673.4011 O: 416.673.4044 C: 416.456.0612 C: 416.505.7615 [email protected] [email protected] GRADE LEVEL RETAIL RETAIL FOR LEASE 220 Bay Street Amenities Map 7 7 1 5 3 2 6 5 6 5 6 9 3 2 11 2 9 8 1 8 7 5 3 4 18 2 6 9 15 1 17 4 3 8 11 13 14 19 12 10 20 10 1 8 16 4 4 1 2 3 Cafe Restaurants Banks Retail Hotels 1 Fairmont Royal York 1 Winners 1 Tim Hortons 1 Moxie’s 1 CIBC Hotel 2 Jack Astor’s 2 Moores Men Clothing 2 One King Street West Cafe Landwer 2 Scotiabank 2 Shoppers Hotel 3 Kellys Landing 3 National Bank 3 3 Starbucks Coffee 3 The St Regis Hotel 4 Bardi’s Steak House 4 Scotiabank 4 Rexall Overview Demographics 4 Tim Hortons 5 Earl’s Kitchen + Bar 5 RBC Bank 5 Harry Rosen 5 Tim Hortons 6 Cactus Club Cafe 6 Bank of Montreal 6 Rego Bespoke • Located at the North West Corner of Bay 0.5km 1.0km 2km 6 Starbucks Coffee 7 Craft Beer Market 7 TD Bank and Wellington Dineen Coffee Yonge-University Subway - Line 1 7 8 Ki Modern Japanese 8 CIBC Population 148,225 302,099 463,900 King Streetcar Lines • Incredible pedestrian exposure 8 Cafe Plenty + Bar 9 Bank of Montreal 9 Walrus Pub • PATH Connected 9 Starbucks Coffee 10 HSBC 10 King Taps • Excellent area and on-site amenities Daytime Population 150,385 317,028 520,100 11 Desjardins Financial 11 IQ Centre • 3 Minute walk to Union Station 12 Marche Movenpick Avg. -

Case 15-10503-MFW Doc 342 Filed 05/07/15 Page 1 of 8 Case 15-10503-MFW Doc 342 Filed 05/07/15 Page 2 of 8 Case 15-10503-MFW Doc 342 Filed 05/07/15 Page 3 of 8

Case 15-10503-MFW Doc 342 Filed 05/07/15 Page 1 of 8 Case 15-10503-MFW Doc 342 Filed 05/07/15 Page 2 of 8 Case 15-10503-MFW Doc 342 Filed 05/07/15 Page 3 of 8 Exhibit A SRF 2014 2072 Case 15-10503-MFW Doc 342 Filed 05/07/15 Page 4 of 8 Exhibit A Nominee Service List Served via Overnight and Next Business Day Service Name Address1 Address2 Address3 City State Zip Country BROADRIDGE JOBS: N83431 51 MERCEDES WAY EDGEWOOD NY 11717 MEDIANT COMMUNICATIONS ATTN: STEPHANIE FITZHENRY/PROXY CENTER 100 DEMAREST DRIVE WAYNE NJ 07470 DEPOSITORY TRUST CO. ATTN: ED HAIDUK 55 WATER STREET 25TH FLOOR NEW YORK NY 10041 DEPOSITORY TRUST CO. ATTN: HORACE DALEY 55 WATER STREET 25TH FLOOR NEW YORK NY 10041 JPMORGAN CHASE BANK, NA (0902) ATTN: JACOB BACK OR PROXY MGR 14201 DALLAS PARKWAY 12TH FLOOR DALLAS TX 75254 1800 S WEST TEMPLE SUITE FIDELITY TRANSFER CO./DRS (7842) ATTN: KEVIN KOPAUNIK OR PROXY MGR 301 SALT LAKE CITY UT 84115 1981 MCGILL COLLEGE AVE LAURENTIAN BANK OF CANADA** (5001) ATTN: SARAH QUESNEL OR PROXY MGR SUITE 100 MONTREAL QC H3A 3K3 CANADA 1981 MCGILL COLLEGE AVE LAURENTIAN BANK OF CANADA/CDS (5001) ATTN: ESTELLE COLLE OR PROXY MGR SUITE 100 MONTREAL QC H3A 3K3 CANADA 3 TIMES SQUARE 28TH BMO NESBITT BURNS TRADING (0018) ATTN: PROXY MGR FLOOR NEW YORK NY 10036 BMO NESBITT BURNS/BMO TRUST COM (4712) ATTN: ANDREA CONSTAND OR PROXY MGR 85 RICHMOND STREET WEST TORONTO ON M5H 2C9 CANADA 180 WELLINGTON ST W, 9TH RBC CAP MARKETS /RBCC (5002/7408) ATTN: SHAREHOLDER SERVICES FLOOR TORONTO ON M5J 0C2 CANADA RBC CAPITAL MARKETS CORPORATION (0235) ATTN: STEVE SCHAFER OR PROXY MGR 510 MARQUETTE AVE SOUTH MINNEAPOLIS MN 55402 155 WELLINGTON ST W, 3RD RBC INVESTOR SERVICES (0901) ATTN: EMMA SATTAR OR PROXY MGR FLOOR TORONTO ON M5V 3L3 CANADA RBC‐ROYAL TRUST 1/CDS (5044/4707) ATTN: ARLENE AGNEW OR PROXY MGR 200 BAY STREET TORONTO ON M5J 2W7 CANADA P.O.