GUJJARS Book Series on History and Culture of Gujjar Tribe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Zone Commissionerate Name Division Name Range Name

Commissionerate State Zone Division Name Range Name Range Jurisdiction Name Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range I On the northern side the jurisdiction extends upto and inclusive of Ajaji-ni-Canal, Khodani Muvadi, Ringlu-ni-Muvadi and Badodara Village of Daskroi Taluka. It extends Undrel, Bhavda, Bakrol-Bujrang, Susserny, Ketrod, Vastral, Vadod of Daskroi Taluka and including the area to the south of Ahmedabad-Zalod Highway. On southern side it extends upto Gomtipur Jhulta Minars, Rasta Amraiwadi road from its intersection with Narol-Naroda Highway towards east. On the western side it extend upto Gomtipur road, Sukhramnagar road except Gomtipur area including textile mills viz. Ahmedabad New Cotton Mills, Mihir Textiles, Ashima Denims & Bharat Suryodaya(closed). Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range II On the northern side of this range extends upto the road from Udyognagar Post Office to Viratnagar (excluding Viratnagar) Narol-Naroda Highway (Soni ni Chawl) upto Mehta Petrol Pump at Rakhial Odhav Road. From Malaksaban Stadium and railway crossing Lal Bahadur Shashtri Marg upto Mehta Petrol Pump on Rakhial-Odhav. On the eastern side it extends from Mehta Petrol Pump to opposite of Sukhramnagar at Khandubhai Desai Marg. On Southern side it excludes upto Narol-Naroda Highway from its crossing by Odhav Road to Rajdeep Society. On the southern side it extends upto kulcha road from Rajdeep Society to Nagarvel Hanuman upto Gomtipur Road(excluding Gomtipur Village) from opposite side of Khandubhai Marg. Jurisdiction of this range including seven Mills viz. Anil Synthetics, New Rajpur Mills, Monogram Mills, Vivekananda Mill, Soma Textile Mills, Ajit Mills and Marsdan Spinning Mills. -

The Importance of Being Ladakhi: Affect and Artifice in Kargil

Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 32 Number 1 Ladakh: Contemporary Publics and Politics Article 13 No. 1 & 2 8-1-2013 The mpI ortance of Being Ladakhi: Affect and Artifice in Kargil Radhika Gupta Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious & Ethnic Diversity, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Gupta, Radhika (2012) "The mporI tance of Being Ladakhi: Affect and Artifice in Kargil," Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 32: No. 1, Article 13. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol32/iss1/13 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RADHIKA GUPTA MAX PLANCK INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF RELIGIOUS & ETHNIC DIVERSITY THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING LADAKHI: AFFECT AND ARTIFICE IN KARGIL Ladakh often tends to be associated predominantly with its Tibetan Buddhist inhabitants in the wider public imagination both in India and abroad. It comes as a surprise to many that half the population of this region is Muslim, the majority belonging to the Twelver Shi‘i sect and living in Kargil district. This article will discuss the importance of being Ladakhi for Kargili Shias through an ethnographic account of a journey I shared with a group of cultural activists from Leh to Kargil. -

Name Address Nature of Payment P

NAME ADDRESS NATURE OF PAYMENT P. NAVEENKUMAR -91774443 NO 139 KALATHUMEDU STREETMELMANAVOOR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED VISHAL TEKRIWAL -31262196 27,GOPAL CHANDRAMUKHERJEE LANEHOWRAH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED LOCAL -16280591 #196 5TH MAIN ROADCHAMRAJPETPH 26679019 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED BHIKAM SINGH THAKUR -21445522 JABALPURS/O UDADET SINGHVILL MODH PIPARIYA CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED ATINAINARLINGAM S -91828130 NO 2 HINDUSTAN LIVER COLONYTHAGARAJAN STREET PAMMAL0CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED USHA DEVI -27227284 VPO - SILOKHARA00 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED SUSHMA BHENGRA -19404716 A-3/221,SECTOR-23ROHINI CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED LOCAL -16280591 #196 5TH MAIN ROADCHAMRAJPETPH 26679019 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAKESH V -91920908 NO 304 2ND FLOOR,THIRUMALA HOMES 3RD CROSS NGRLAYOUT,CLAIMS CHEQUES ROOPENA ISSUED AGRAHARA, BUT NOT ENCASHED KRISHAN AGARWAL -21454923 R/O RAJAPUR TEH MAUCHITRAKOOT0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED K KUMAR -91623280 2 nd floor.olympic colonyPLOT NO.10,FLAT NO.28annanagarCLAIMS west, CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MOHD. ARMAN -19381845 1571, GALI NO.-39,JOOR BAGH,TRI NAGAR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED ANIL VERMA -21442459 S/O MUNNA LAL JIVILL&POST-KOTHRITEH-ASHTA CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAMBHAVAN YADAV -21458700 S/O SURAJ DEEN YADAVR/O VILG GANDHI GANJKARUI CHITRAKOOTCLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MD SHADAB -27188338 H.NO-10/242 DAKSHIN PURIDR. AMBEDKAR NAGAR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MD FAROOQUE -31277841 3/H/20 RAJA DINENDRA STREETWARD NO-28,K.M.CNARKELDANGACLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAJIV KUMAR -13595687 CONSUMER APPEALCONSUMERCONSUMER CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MUNNA LAL -27161686 H NO 524036 YARDS, SECTOR 3BALLABGARH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED SUNIL KUMAR -27220272 S/o GIRRAJ SINGHH.NO-881, RAJIV COLONYBALLABGARH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED DIKSHA ARORA -19260773 605CELLENO TOWERDLF IV CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED R. -

Primary Census Abstract, Series-31

~~ ~I~d qft \if...,JI OI'11 2001 CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 ~ffi-31 Series-31 'tIT2:I ft:l Cf) \J1 ~ ~ I UI ~ I '("II '< Primary Census Abstract WR \JHfi'L(~H : ftHuft q)"-5 ~ \11'1fi'LclIl : ~ q)"-6, ~ \11 '1 t1'LclI 1 : ~ en-7 3f1~ d \111 Rt ll) qft \11 +~4 'LclIl : ~ q)"-8, 3f 1~fil d \11 '1 \111 Rt m<tt \11;:Ifi'LclIl : ~ co -9 Total Population: Table A-5 Institutional Population: Table A-G, Houseless Population: Table A-7 Scheduled Castes Population: Table A-B, Scheduled Tribes Population: Table A-9 Vfrl J IUl'11 PI~~II(>1l1, TJ1crr Directorate of Census Operations, Goa Product Code Number 30-009-2001-Cen-Book ii !,H-qICl'iI ......................... , ................. ,"."' .. ",."', ... ',.', ............ ,."., .. ,, .... ,, .... , .... " .. " .. , .. ,.".,. v-vi 3IT~"'."'., .. ,.".,., .. , ..... ,." .. , .. " .. """".".".,., .. ",", .. , .... "",",.".,', .. , .... ,.,, .. , .. ,."".,."",.,.", IX ~ ~ ~ it "',",", ... ,.. " .. ,., ... ,..... ".".,.".,, .................... ,." ........ ,..... ,.......... ,", ..... ,",xi-xxi 'QTCRl?~9 ........................ , .................. , ......................................................................... xxiii-xxv ~ \J1'i l IOI'i1 fiCfJ<:>q'iI~ lfCT l:lft~ ........ " ........................................ " ....... "" .......... " .. xxvii-xxxv ~~ Pc) ~ ~ .. I V11Q'l'9-~!:! tkllQ ............................ ".,',.,",." .... " .. ,.".,"", ... : ......... , ......................... XXXVII-X fc)~c>ll"iOIIC1iCf) fclq'!fUl~~i ................................................................................................... -

University of Kashmir Srinagar

KULR KASHMIR UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW Vol. XXIII 2016 School of Law University of Kashmir Srinagar Vol. XXIII ISSN 0975-6639 Cite this Volume as: XXIII KULR (2016) Kashmir University Law Review is Published Annually Annual Subscription: Inland: ` 500.00 Overseas: $ 15.00 © Head, School of Law University of Kashmir Srinagar All rights reserved. No Part of this journal may be reproduced in any form whatsoever, e.g., by photoprint, microfilm, or any other means without written permission from the publishers. E-mail: [email protected] Printed at: Crown Printing Press Computer Layout and Design by: Shahnawaz Ahmad Khosa Phone No: 7298559181 KASHMIR UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW Patron Prof. (Dr.) Khurshid I. Andrabi Vice – Chancellor University of Kashmir Chief Editor Prof. Mohammad Hussain Head and Dean School of Law University of Kashmir Editors Dr. Fareed Ahmad Rafiqi Dr. Mir Junaid Alam Editorial Board Prof. Farooq Ahmad Mir Prof. Mohammad Ayub Dr. Beauty Banday Dr. Shahnaz The editors, publisher and printer do not claim any responsibility for the views expressed by the contributors and for the errors, if any, in the information contained in this journal. With Best Compliments From Prof. Mohammad Hussain Head & Dean School of Law University of Kashmir Srinagar CONTENTS S. No. Page No. Articles 1 Human Rights and their Protection 1-32 A. M. Matta 2 A Constitutional Perspective on Article 35-A and its 33-54 Role in Safeguarding the Rights of Permanent Residents of the State of J&K Altaf Ahmad Mir Mir Mubashir Altaf 3 Anton Piller– Analysed and Catalysed 55-82 S. Z. Amani 4 An Appraisal of Fraud Rule Exception in Documentary 83-104 Credit Law with Special Emphasis on India Susmitha P Mallaya 5 The Expanding Horizons of Professional Misconduct of 105-120 Advocates vis-a-vis Contempt of Court: A Review of the Code of Ethics of Advocates Vijay Saigal 6 Eagle Eye on the New Age of Corporate Governance: A 121-136 Critical Analysis Qazi M. -

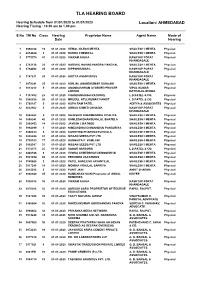

Tla Hearing Board

TLA HEARING BOARD Hearing Schedule from 01/01/2020 to 01/01/2020 Location: AHMEDABAD Hearing Timing : 10.30 am to 1.00 pm S.No TM No Class Hearing Proprietor Name Agent Name Mode of Date Hearing 1 3958238 19 01-01-2020 HEMAL NILESH MEHTA SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 2 4014884 3 01-01-2020 RUDRA CHEMICAL SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 3 3775574 41 01-01-2020 VIKRAM AHUJA KASHYAP POPAT Physical KHANDAGALE 4 3743128 25 01-01-2020 HARSHIL NAVINCHANDRA PANCHAL SHAILESH I MEHTAPhysical 5 3794452 25 01-01-2020 DIPESHKUMAR L KASHYAP POPAT Physical KHANDAGALE 6 3767211 20 01-01-2020 ADITYA ASSOCIATES KASHYAP POPAT Physical KHANDAGALE 7 3979241 25 01-01-2020 KUNJAL ANANDKUMAR DUNGANI SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 8 3813212 5 01-01-2020 ANANDASHRAM AYURVED PRIVATE VIPUL KUMAR Physical LIMITED DAYHALAL BHEDA 9 3197802 25 01-01-2020 CHANDANSINGH RATHORE L.D.PATEL & CO. Physical 10 3980535 30 01-01-2020 MRUDUL ATULKUMAR PANDIT L.D.PATEL & CO. Physical 11 3760197 5 01-01-2020 KUPA RAM PATEL. ADITYA & ASSOCIATES Physical 12 3632502 5 01-01-2020 ABBAS AHMED UCHADIA KASHYAP POPAT Physical KHANDAGALE 13 3802482 5 01-01-2020 RAJESHRI DHARMENDRA PIPALIYA SHAILESH I MEHTAPhysical 14 3958241 42 01-01-2020 KAMLESH DHANSUKHLAL BHATELA SHAILESH I MEHTAPhysical 15 3966453 14 01-01-2020 JAYESH L RATHOD SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 16 3992099 1 01-01-2020 NIMESHBHAI CHIMANBHAI PANSURIYA SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 17 4008824 5 01-01-2020 CARRYING PHARMACEUTICALS SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 18 3992098 31 01-01-2020 NISSAN SEEDS PVT LTD SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 19 3738100 17 01-01-2020 KANHAIYA P. -

BA REG. POST DATA.Xlsx

FACULTY -BACHELOR OF ARTS (REGULAR) 10TH CONVOCATION DEGREE DATE - 29-07-2021 SR.N DEGREE NAME SEAT NO. ADDERES PINCODE MOB BARCODE AMOUNT O. SR.NO. Jakhau City: Jakhau Abdasa District: Kachchh State: Gujarat 1 1 Abda Vijaysinh Rupsangji *200950 370640 919998722671 EG779368059IN 41.3 Pincode: 370640 Parmeshwar Gali Bhuj Nagor Society, Nagor, Bhuj Kutch 2 2 Ahir Archana Mahendrabhai 121199 370001 919909072954 EG779368062IN 41.3 Pincode: 370001 3 5 Ahir Manish Dhanji *120147 Jagruti Society Village - Kukma Ta - Bhuj Pincode: 370105 370105 919974326940 EG779368181IN 41.3 Ratnal City: Ratnal Anjar District: Kachchh State: Gujarat 4 7 Ahir Natvar Ruda Arjan 180044 370105 919913186348 EG779368178IN 41.3 Pincode: 370105 Vill- Kathda, Gurumukhdas, Vadi Vistar Tal- Mandvi- 5 9 Amarnani Jyoti Maheshbhai 121042 370465 919825808265 EG779368218IN 41.3 Kachchh Pincode: 370465 Dharm K Antanni Tenament 18 Jaynagar Bhuj Kutch 6 14 Antani Dharm Kinnarbhai *120077 370001 919737204263 EG779368195IN 41.3 Pincode: 370001 Balkrushn Nagar Vill Gadhsisa Ta Mandvi Kutch Pincode: 7 15 Anthu Varshaben Vinod 120389 370445 919979334783 EG779368204IN 41.3 370445 8 16 Ashar Bhavika Bipinbhai 120303 34 G Shree Hari Nagar 3 Mirzapar Tal Bhuj Pincode: 370001 370001 919687731710 EG779368297IN 41.3 Ahir Vas Village - Jaru Ta - Anjar Kachchh Gujarat Pincode: 9 18 Avadiya Dinesh Shamajibhai 120494 370110 919106579704 EG779368306IN 41.3 370110 Near Hanuman Temple, Uplovas , Baladiya,Bhuj.Kachchh 10 19 Ayadi Sachin Nanjibhai 120455 Near Hanuman Temple,Uplovas,Baladiya,Bhuj , -

A Curriculum to Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2007 A Curriculum To Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India Calvin N. Joshua Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Joshua, Calvin N., "A Curriculum To Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India" (2007). Dissertation Projects DMin. 612. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/612 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT A CURRICULUM TO PREPARE PASTORS FOR TRIBAL MINISTRY IN INDIA by Calvin N. Joshua Adviser: Bruce L. Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: A CURRICULUM TO PREPARE PASTORS FOR TRIBAL MINISTRY IN INDIA Name of researcher: Calvin N. Joshua Name and degree of faculty adviser: Bruce L. Bauer, DMiss. Date Completed: September 2007 Problem The dissertation project establishes the existence of nearly one hundred million tribal people who are forgotten but continue to live in human isolation from the main stream of Indian society. They have their own culture and history. How can the Adventist Church make a difference in reaching them? There is a need for trained pastors in tribal ministry who are culture sensitive and knowledgeable in missiological perspectives. Method Through historical, cultural, religious, and political analysis, tribal peoples and their challenges are identified. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2 Contact3 Micr Code

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN NO 26. MG ROAD AND ABERDEEN BAZAR , NICOBAR PORT BLAIR -744101 704412829 704412829 ISLAND ANDAMAN PORT BLAIR ,A & N ISLANDS PORT BLAIR IBKL0001498 8 7044128298 8 744259002 UPPER GROUND FLOOR, #6-5-83/1, ANIL ANIL NEW BUS STAND KUMAR KUMAR ANDHRA ROAD, BHUKTAPUR, 897889900 ANIL KUMAR 897889900 PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD ADILABAD 504001 ADILABAD IBKL0001090 1 8978899001 1 1ST FLOOR, 14- 309,SREERAM ENCLAVE,RAILWAY FEDDER ROADANANTAPURA ANDHRA NANTAPURANDHRA ANANTAPU 08554- PRADESH ANANTAPUR ANANTAPUR PRADESH R IBKL0000208 270244 D.NO.16-376,MARKET STREET,OPPOSITE CHURCH,DHARMAVA RAM- 091 ANDHRA 515671,ANANTAPUR DHARMAVA 949497979 PRADESH ANANTAPUR DHARMAVARAM DISTRICT RAM IBKL0001795 7 515259202 SRINIVASA SRINIVASA IDBI BANK LTD, 10- RAO RAO 43, BESIDE SURESH MYLAPALL SRINIVASA MYLAPALL MEDICALS, RAILWAY I - RAO I - ANDHRA STATION ROAD, +91967670 MYLAPALLI - +91967670 PRADESH ANANTAPUR GUNTAKAL GUNTAKAL - 515801 GUNTAKAL IBKL0001091 6655 +919676706655 6655 18-1-138, M.F.ROAD, AJACENT TO ING VYSYA BANK, HINDUPUR , ANANTAPUR DIST - 994973715 ANDHRA PIN:515 201 9/98497191 PRADESH ANANTAPUR HINDUPUR ANDHRA PRADESH HINDUPUR IBKL0001162 17 515259102 AGRICULTURE MARKET COMMITTEE, ANANTAPUR ROAD, TADIPATRI, 085582264 ANANTAPUR DIST 40 ANDHRA PIN : 515411 /903226789 PRADESH ANANTAPUR TADIPATRI ANDHRA PRADESH TADPATRI IBKL0001163 2 515259402 BUKARAYASUNDARA M MANDAL,NEAR HP GAS FILLING 91 ANDHRA STATION,ANANTHAP ANANTAPU 929710487 PRADESH ANANTAPUR VADIYAMPETA UR -

February 2008

ExamSeatNo Trial Employee Name Designation Secretariate Department Institute Practical Theory Total Result Exam Date PATEL DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890117008 1 BIPINCHANDRA JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 25 8 33 FAIL 30/01/2008 DEPARTMENT ISHWERBHAI TREASURY OFFICE PATEL DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890117009 1 MAHENDRABHAI JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 5 5 10 FAIL 30/01/2008 DEPARTMENT CHHAGANBHAI TREASURY OFFICE BRAHMBHATT DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890117010 1 KETANKUMAR JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 44 26 70 PASS 30/01/2008 DEPARTMENT HARIKRISHAN TREASURY OFFICE PANDYA DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890117011 1 PARESHKUMAR JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 27 4 31 FAIL 30/01/2008 DEPARTMENT PREMJI TREASURY OFFICE PRAJAPATI DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT DEPUTY FINANCE 69890117012 1 SAVAJIBHAI ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 29 25 54 PASS 30/01/2008 ACCOUNTANT DEPARTMENT CHATARABHAI TREASURY OFFICE PANDYA DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890117013 1 BIPINCHANDRA JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 31 26 57 PASS 30/01/2008 DEPARTMENT MANSUKHLAL TREASURY OFFICE MALEK DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890117014 1 NAGARKHAN JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 26 4 30 FAIL 30/01/2008 DEPARTMENT KALAJIBHAI TREASURY OFFICE PATEL DIRECTARATE OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890117015 1 AMBARAM JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 19 7 26 FAIL 30/01/2008 DEPARTMENT MANAGIBHAI TREASURY OFFICE HOME PATEL RADIO DEPARTMENT/POLI COMMANDANT 10190146001 1 BABULAL HOME DEPARTMENT 40 25 65 PASS 06/02/2008 TECHNICIAN CE WIRELESS S R P F GR-2 POPATLAL BRANCH ASARI HEAD POLICE KHADIA POLICE 10190146002 1 RAJESHKUMAR HOME DEPARTMENT 0 0 0 ABSENT 06/02/2008 QUANSTABLE DEPARTMENT STATION JIVJIBHAI BHATI SHAHIBUAG POLICE 10190146003 1 BHARATSINH UPC HOME DEPARTMENT POLICE 0 0 0 ABSENT 06/02/2008 DEPARTMENT MANUJI STATION CHITRODA SHAHIBUAG BHUPENDRASIN POLICE 10190146004 1 UPC HOME DEPARTMENT POLICE 0 0 0 ABSENT 06/02/2008 H DEPARTMENT STATION PRATPSINH ESHARANI POLICE THE 10190146005 1 JAYDEV DRIVER P.C. -

Tribal Population and Development Policies in the Himalayan State of Jammu and Kashmir: a Critical Analysis

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 3 Issue 1ǁ January. 2014 ǁ PP.18-26 Tribal Population and Development Policies in the Himalayan State of Jammu and Kashmir: A Critical Analysis 1,Touseef Iqbal Butt , 2,Ruhi Gupta 1,Research Scholar Sociology (Contractual Lecturer In Govt. Degree College Kishtwar). 2,Research scholar Department Of sociology university of Jammu. ABSTRACT : India is home to tribal population of about 85 million, with more than 700 groups each with their distinct cultures, social practices, religions, dialects and occupations and are scattered in all States and Union Territories in India. The Tribes, like the Scheduled Castes, is the most socially, economically and educationally disadvantaged, marginalized and excluded groups in our country. The wide-spread discrimination against scheduled groups has long histories in India. However the status of this community in the state of Jammu and Kashmir is somewhat different from their counterpart in other part of the country. In Jammu and Kashmir, the tribal people are very affluent, highly educated, politically awared and have good number in white-collar jobs. In this context and with this backdrop, this is a modest attempt to study the demographic particulars of tribal and the development policies in India in general and Jammu and Kashmir in particular. KEYWORDS: Tribes • Tribal Population • Tribal Development • Constitutional Safeguards • Scheduled Tribes • Jammu and Kashmir I. INTRODUCTION India is a pluralist and multi-cultural country, with rich diversity, reflected in the multitude of culture, religions, languages and racial stocks. -

Educational Status of Tribals of Jammu & Kashmir

International Journal of Social Science : 3(3): 275-284, Sept. 2014 DOI Number : 10.5958/2321-5771.2014.00004.0 Educational Status of Tribals of Jammu & Kashmir: A Case of Gujjars and Bakarwals Umer Jan Sofi Discipline of Sociology, IGNOU, New Delhi-110068, India. Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Education as a means of advancement of capacity, well –being and opportunity is uncontested and more so among communities on the periphery. In India, marked improvements in access and to some extent in quality of education in tribal areas have occurred and stem from various government and non-government initiatives. However, the number of out-of-school children continues to be several millions mainly due to lack of proper infrastructure, teacher absenteeism and attitude, parental poverty, seasonal migration, lack of interest and parental motivation etc. The scenario of tribal education is no way different than other states in Jammu and Kashmir. In Jammu & Kashmir the overall literacy rate of the Scheduled tribes as per the census 2001 is 3.7percent which is much lower than the national average of 47.1percent aggregated for all S.Ts. Though various efforts have been made by the government for the development of education among tribal communities but much more still needs to do. In this paper an attempt has been made to explore the existing educational status of two prominent tribal communities of Jammu and Kashmir- Gujjars and Bakarwals. The study has been conducted in five tribal villages of district Anantnag. 124 households were selected with the help of stratified sampling for the survey.