Chris Burden's Shoot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DAVID SALLE Born 1952, Norman, Oklahoma, USA. Currently Lives And

DAVID SALLE Born 1952, Norman, Oklahoma, USA. Currently lives and works in New York. Education 1975 California Institute of the Arts, MFA. 1973 California Institute of the Arts, BFA. Awards 2016 American Academy of Arts and Letters 2015 National Academy of Art 1986 Guggenheim Fellowship for Theater Design Selected Solo Exhibitions 2018 David Salle: Paintings 1985 -1995, Skarstedt, New York, USA. 2017 David Salle: Ham and Cheese and Other Paintings, Skarstedt, New York, USA. David Salle: New Paintings, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris, FR 2016 David Salle, Lehmann Maupin Gallery, Hong Kong, HK. David Salle: Inspired by True-Life Events, CAC Málaga, Málaga, ES. 2015 David Salle, Skarstedt, New York, USA. Debris, Dallas Contemporary, Dallas, USA. 2014 Maureen Paley, London, UK. Collage, Mendes Wood D, São Paulo, BR. 2013 Ghost Paintings, Skarstedt Gallery, New York, USA. David Salle/ Francis Picabia, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris, FR. David Salle: Ghost Paintings, The Arts Club, Chicago, USA. Tapestries/ Battles/ Allegories, Lever House Art Collection, New York, USA. Leeahn Gallery, Daegu, KR. Leeahn Gallery, Seoul, KR. 2012 Gerhardsen Gerner, Berlin, DE. Ariel and Other Spirits, The Arnold and Marie Schwartz Gallery Met, Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, New York, USA. 2011 David Salle Recent Paintings, Mary Boone Gallery, New York, USA. Maureen Paley, London, UK. 2010 Mary Boone Gallery, New York, USA. 2009 Héritage du Pop Art, Kestnergesellschaft, Hannover, DE. 2008 Galleri Faurschou, Copenhagen, DK. Studio d’Arte Raffaelli, Trento, IT. 2007 Galleria Cardi, Milan, IT. David Salle, New Works, Galerie Thaddeaus Ropac, Salzburg, AT. Bearding The Lion In His Den, Deitch Projects, New York, USA. -

Curating Now: Imaginative Practice/Public Responsibility Full Text Edited by Paula Marincola

QUESTIONS OF PRACTICE Curating Now: Imaginative Practice/Public Responsibility Full Text Edited by Paula Marincola THE PEW CENTER FOR ARTS & HERITAGE / PCAH.US / @PEWCENTER_ARTS CURATING NOW: IMAGINATIVE PRACTICE/PUBLIC RESPONSIBILITY OCT 14-15 2000 Paula Marincola Robert Storr Symposium Co-organizers Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative Funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts Administered by The University of the Arts The Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative is a granting program funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and administered by The University of the Arts, Philadelphia, that supports exhibitions and accompanying publications.“Curating Now: Imaginative Practice/Public Responsibility” has been supported in part by the Pew Fellowships in the Arts’Artists and Scholars Program. Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative 230 South Broad Street, Suite 1003 Philadelphia, PA 19102 215-985-1254 [email protected] www.philexin.org ©2001 Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative All rights reserved ISBN 0-9708346-0-8 Library of Congress catalog card no. 2001 131118 Book design: Gallini Hemmann, Inc., Philadelphia Copy editing: Gerald Zeigerman Printing: CRW Graphics Photography: Michael O’Reilly Symposium and publication coordination: Alex Baker CONTENTS v Preface Marian Godfrey vii Introduction and Acknowledgments Paula Marincola SATURDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2000 AM 3 How We Do What We Do. And How We Don’t Robert Storr 23 Panel Statements and Discussion Paul Schimmel, Mari-Carmen Ramirez, Hans-Ulrich Obrist,Thelma Golden 47 Audience Question and Answer SATURDAY, -

HOWARD SINGERMAN Phyllis and Joseph Caroff Chair Department Of

HOWARD SINGERMAN Phyllis and Joseph Caroff Chair Department of Art and Art History Hunter College of the City University of New York (212) 772-5051 [email protected] EDUCATION Doctoral Program in Art History and Visual and Cultural Studies University of Rochester, New York Ph.D. 1996: “The Discourse of the Artist in the University” Claremont Graduate School, Claremont, California, M.F.A. 1978 Antioch College, Yellow Springs, Ohio, B.A. 1975 TEACHING and PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS Professor of Art History Phyllis and Joseph Chair of the Department of Art and Art History Hunter College of the City University of New York August 2013 to the present Professor and Department Chair McIntire Department of Art University of Virginia, Charlottesville August 2011 to August 2013 (Associate Professor, August 2001 to August 2011) (Assistant Professor, September 1996 to August 2001) BOOKS Sharon Lockhart: Pine Flat. London: Afterall Books, One Work Series, 2019 OCTOBER Files: Sherrie Levine (editor). Cambridge: MIT Press, 2018 Art History, After Sherrie Levine. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012 Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999 BOOK CHAPTERS “Old Divisions and the New Art History,” in Art History and Emergencies: Crises in Visual Arts and the Humanities, ed. David Breslin and Darby English. Williamstown, Mass.: Clark Art Institute and Yale University Press, 2016 “Janet Wolff’s Artists,” in Porous Boundaries: Art and Essays, ed. Cyril Reade and David Peters Corbett. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015 “I [Like] Wade Guyton,” in The Happy Fainting of Painting: Ein reader zur zeitgenössischen malerei, ed. -

Ucla Department of Art Faculty 1920-2007

UCLAUCLA DEPARTMENTDEPARTMENT OFOF ARTART FACULTYFACULTY 1920-20071920-2007 Annita Delano Stanton MacDonald Wright Jan Schmalix Constance Mallinson Richard Jackson Christopher Williams Steven Criqui Thaddeus Stussy Dorothy Brown Inez Johnson Gordon Betty Lee Susan Mogul Jorge Saia Michael Tims Strode Joel Otterson Pipilotti Rist Tessa Chasteen Nunes William Brice Tony Rosenthal John Paul Jill Geigerich Lutz Bacher Linda Day Mark Durant Dara Friedman Chris Miles Ann Preston Benjamin Jones Sam Amato Elliot Elgart Robert Heinecken Joseph Lewis Todd Gray Robbie Conal Liz Larner Weissman Kaucyila Brooke Ernie Larsen Mark Oliver Andrews Arthur Levine Raymond Brown Lee Anne Walsh Megan Williams Jeff Wasserman Judie Wyse Hans Broek Fred Hoffman Laura Owens Bart Mullican Charles Garabedian Llyn Foulkes Richard Bamber Jacci Den Hartog James Hayward Joan Exposito Jennifer Bolande Won Ju Lim Francesco Diebenkorn Robert Fichter Richard Joseph Leslie Jonas Carolee Schneeman Judy Baca Nancy Evans Siqueiros Walead Beshty Shannon Ebner Mari Biller James Weeks William Childress Tony Berlant Kim Dingle Jim Shaw Diana Thater Dan Mc Cleary Eastman David Lamelas Dave Muller Kenneth Mark Greenwold James Valerio Jim Doolin Adrian Erika Rothenberg John Mason Holly Crawford Oppriecht Renee Petropoulos Paul Schimmel John Saxe Mark McFadden Gary Lloyd Judith Golden Daniel Freeman Charles Gaines Joan Mahony Ralph Sonsini Denise Spampinato Derek Boshier Meg Ed Moses Ed Ruscha Laddie John Dill Guy Dill Rugoff James Welling Dana Duff John Baldessari Cranston M.A. Greenstein -

Jori Finkel, “Open the Storeroom: Let's Put on a Show,”

9/24/2016 The New Season Art In Los Angeles, the Museum of Contemporary Art Digs In to Its Own Collection NYTimes.com This copy is for your personal, noncommercial use only. You can order presentationready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers here or use the "Reprints" tool that appears next to any article. Visit www.nytreprints.com for samples and additional information. Order a reprint of this article now. September 13, 2009 THE NEW SEASON | ART Open the Storeroom: Let’s Put on a Show By JORI FINKEL LOS ANGELES WHEN the financial crisis at the Museum of Contemporary Art here made headlines last year, many in the art world questioned why the museum was spending so much on temporary exhibitions while the bulk of its impressive collection languished in storage. It’s not just a budget issue but also one of museum identity: if a museum is known for organizing big but shortlived surveys and staging shows on loan from New York, is it giving visitors enough to feel proprietary excitement about and inspire them to keep coming back? So there was clearly a silver lining when the museum announced this year that to save money it would cancel several exhibitions and for the first time devote both its buildings — some 50,000 square feet — to its permanent collection. This installation will run from Nov. 15 through May 2010, when some galleries will make room for an Arshile Gorky show. Until then, expect to see about 500 works handpicked by the chief curator, Paul Schimmel, which is less than 10 percent of the museum’s overall holdings but promises to speak volumes about the history of contemporary art. -

Deborah Remington

BORTOLAMI Deborah Remington Illustrated Chronology Deborah Remington’s work has been widely collected by major institutions including the Whitney Museum of American Art, Centre Pompidou, The Art Institute of Chicago, Smithsonian Museum of American Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Carnegie Museum of Art, and the Cleveland Museum of Art, among dozens of other museums. During her lifetime Remington exhibited at such prestigious galleries as the Dilexi Gallery in San Francisco, the Bykert Gallery in New York and Galerie Darthea Speyer in Paris. A twenty-year retrospective (1963-1983) curated by Paul Schimmel opened at the Orange County Museum of Art in California in 1983 and traveled to the Oakland Museum of California, among other venues. Remington was the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship (1984) a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship (1979) and a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant (1999). 39 WALKER STREET NEW YORK NY 10013 T 212 727 2050 BORTOLAMIGALLERY.COM Deborah Remington in her New York studio, 1974 1930 Born in Haddonfield, New Jersey 1944 After a four-year battle with leukemia, Remington’s father passes away. Remington and her mother relocate to Pasadena, CA. 1945-48 Attends Pasadena High School and Pasadena Junior College, where she meets future collaborators Wally Hedrick, John Ryan and David Simpson, friends with whom Remington would found the influential 6 Gallery in San Francisco. 1949 Enrolls in the California School of Fine Arts, San Francisco (now the San Francisco Art Institute) and studies with Elmer Bischoff, Deborah Remington, Jack Spicer, Hayward King, John Ryan, and Wally Hedrick David Park, and Clyfford Still, among others. -

From Minimalism to Performance Art: Chris Burden, 1967–1971

From Minimalism to Performance Art: Chris Burden, 1967–1971 Matthew Teti Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Matthew Teti All rights reserved ABSTRACT From Minimalism to Performance Art: Chris Burden, 1967–1971 Matthew Teti This dissertation was conceived as an addendum to two self-published catalogs that American artist Chris Burden released, covering the years 1971–1977. It looks in-depth at the formative work the artist produced in college and graduate school, including minimalist sculpture, interactive environments, and performance art. Burden’s work is herewith examined in four chapters, each of which treats one or more related works, dividing the artist’s early career into developmental stages. In light of a wealth of new information about Burden and the environment in which he was working in the late 1960s and early 1970s, this dissertation examines the artist’s work in relation to West Coast Minimalism, the Light and Space Movement, Environments, and Institutional Critique, above and beyond his well-known contribution to performance art, which is also covered herein. The dissertation also analyzes the social contexts in which Burden worked as having been informative to his practice, from the beaches of Southern California, to rock festivals and student protest on campus, and eventually out to the countercultural communes. The studies contained in the individual chapters demonstrate that close readings of Burden’s work can open up to formal and art-historical trends, as well as social issues that can deepen our understanding of these and later works. -

Jack Goldstein in Los Angeles

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Fall 1-5-2018 Jack Goldstein in Los Angeles Kirby Michelle Woo CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/241 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Jack Goldstein in Los Angeles by Kirby Michelle Woo Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2017 Thesis Sponsor: January 3, 2018 Howard Singerman Date Signature January 3, 2018 Joachim Pissarro Date Signature of Second Reader i. Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii List of Illustrations iii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 5 Chapter 2 24 Chapter 3 42 Conclusion 69 Bibliography 71 Illustrations 74 ii. Acknowledgments This paper would not have been possible without the support of faculty and friends at Hunter College who have provided me guidance and encouragement throughout the years. I am especially thankful to my advisor Dr. Howard Singerman who actively participated in this project and provided the structure, insight, and critical feedback necessary to help me bring this work to completion. I am also grateful to Dr. Joachim Pissarro for his time as my second reader. I would also like to thank my editor, Viola McGowan for her patience and expertise, as well as Dr. David E. -

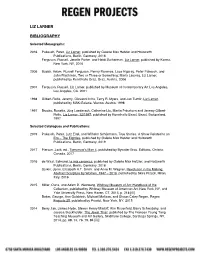

Liz Larner Bibliography

LIZ LARNER BIBLIOGRAPHY Selected Monographs: 2016 Pakesch, Peter, Liz Larner, published by Galerie Max Hetzler and Holzwarth Publications, Berlin, Germany, 2016 Ferguson, Russell, Jenelle Porter, and Heidi Zuckerman, Liz Larner, published by Karma, New York, NY, 2016 2006 Budak, Adam, Russell Ferguson, Penny Florence, Luce Irigaray, Peter Pakesch, and John Rajchman, Two or Three or Something: Maria Lassnig, Liz Larner, published by Kunsthalle Graz, Graz, Austria, 2006 2001 Ferguson, Russell, Liz Larner, published by Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, 2001 1998 Gilbert-Rolfe, Jeremy, Giovanni Intra, Terry R. Myers, and Jan Tumlir, Liz Larner, published by MAK-Galerie, Vienna, Austria, 1998 1997 Brooks, Rosetta, Jürg Laederach, Catherine Liu, Martin Prinzhorn and Jeremy Gilbert- Rolfe, Liz Larner: 12/1997, published by Kunsthalle Basel, Basel, Switzerland, 1997 Selected Catalogues and Publications: 2019 Pakesch, Peter, Lutz Eitel, and Wilhelm Schürmann, True Stories. A Show Related to an Era – The Eighties, published by Galerie Max Hetzler and Holzwarth Publications, Berlin, Germany, 2019 2017 Pierson, Jack, ed., Tomorrow’s Man 4, published by Bywater Bros. Editions, Ontario, Canada, 2017 2016 de Waal, Edmund, la mia ceramica, published by Galerie Max Hetzler, and Holzwarth Publications, Berlin, Germany, 2016 Sorkin, Jenni, Elizabeth A.T. Smith, and Anne M. Wagner, Revolution in the Making: Abstract Sculpture by Women, 1947 – 2016, published by Skira Rizzoli, Milan, Italy, 2016 2015 Miller, Dana, and Adam D. Weinberg, -

Kristine Stiles

Concerning Consequences STUDIES IN ART, DESTRUCTION, AND TRAUMA Kristine Stiles The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London KRISTINE STILES is the France Family Professor of Art, Art Flistory, and Visual Studies at Duke University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2016 by Kristine Stiles All rights reserved. Published 2016. Printed in the United States of America 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 12345 ISBN13: 9780226774510 (cloth) ISBN13: 9780226774534 (paper) ISBN13: 9780226304403 (ebook) DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226304403.001.0001 Library of Congress CataloguinginPublication Data Stiles, Kristine, author. Concerning consequences : studies in art, destruction, and trauma / Kristine Stiles, pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 9780226774510 (cloth : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226774534 (paperback : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226304403 (ebook) 1. Art, Modern — 20th century. 2. Psychic trauma in art. 3. Violence in art. I. Title. N6490.S767 2016 709.04'075 —dc23 2015025618 © This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper). In conversation with Susan Swenson, Kim Jones explained that the drawing on the cover of this book depicts directional forces in "an Xman, dotman war game." The rectangles represent tanks and fortresses, and the lines are for tank movement, combat, and containment: "They're symbols. They're erased to show movement. 111 draw a tank, or I'll draw an X, and erase it, then redraw it in a different posmon... -

Jason Rhoades Born 1965 in Newcastle, California

This document was updated March 2, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Jason Rhoades Born 1965 in Newcastle, California. Died 2006 in Los Angeles. EDUCATION 1991-1993 M.F.A., University of California, Los Angeles 1988 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Maine 1986-1988 B.F.A., San Francisco Art Institute 1985-1986 California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Jason Rhoades: Tijuanatangierchandelier, David Zwirner, New York 2017 Jason Rhoades, The Brant Foundation, Art Study Center, Greenwich, Connecticut Jason Rhoades: Installations, 1994-2006, Hauser Wirth & Schimmel, Los Angeles 2015 Jason Rhoades: Multiple Deviations, The Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts 2014 Jason Rhoades: Perfect Process, PARADISE / A Space for Screen Addiction, LECLERE- Maison de Ventes, Marseille [part of Oracular/Vernacular] Jason Rhoades: PeaRoeFoam, David Zwirner, New York [catalogue published in 2015] 2013 Jason Rhoades, Four Roads, Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia [itinerary: Kunsthalle Bremen, Germany; BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, England] [catalogue] 2010 Jason Rhoades: 1: 12 Perfect World, Hauser & Wirth, London Peter Bonde & Jason Rhoades: Half Snowball, Andersens Contemporary, Copenhagen [two- person exhibition] 2007 Jason Rhoades: Black Pussy, David Zwirner, New York [catalogue] Jason Rhoades: Multiples (Sculptures 1993-98), El Sourdog Hex, Berlin 2006 Jason Rhoades: Black Pussy Soirée Cabaret Macramé, Jason Rhoades Studio, Los Angeles Jason Rhoades: Tijuanatanjierchandelier, Centro de Arte Contemporáneo de Málaga, Málaga, Spain 2005 Jason Rhoades: Black Pussy…and the Pagan Idol Workshop, Hauser & Wirth, London Jason Rhoades, Le Magasin - Centre National d’Art Contemporain, Grenoble, France Jason Rhoades: Macramé Cabaret Pussy Harvest, Mapa Teatro, Bogotá, Colombia Jason Rhoades. -

Llyn Foulkes Bloody Heads October 27 Through December 17, 2011

210 ELEVENTH AVENUE, SECOND FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10001 P. 212 365 9500 www.kentfineart.net Llyn Foulkes Bloody Heads October 27 through December 17, 2011 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Kent Fine Art’s upcoming exhibition Llyn Foulkes: Bloody Heads will be the first show of new paintings by Foulkes in New York since 2007, and an in-depth look at his personal collection of “bloody heads” completed over the past decade. While his previous exhibitions of 2005 and 2007 focused on single emblematic tableaus (The Lost Frontierand Deliverance), the current exhibition will present an intimate and introspective group of works from his Los Angeles studio. Beginning in the early seventies, Foulkes turned up the volume of Baconian horror in his first series of portrait heads, keenly described by Rosetta Brooks in the catalogue for his traveling retrospective organized by the Laguna Art Museum in 1995: Contemporary life is full of all kinds of monsters which many of us either ignore or conceal. Foulkes does neither. His art is constantly grappling with the social schizophrenia characteristic of America, including its inherent violence and its quiet vulnerability. A pioneer of the L.A. Hot and Cool scene of the sixties (along with John Baldessari, Wallace Berman, Chris Burden, George Herms, Edward Kienholz, Bruce Nauman, Kenneth Price, and others), Foulkes has continued to be an innovator. His breakthrough tableau work Pop (1986–1990) was exhibited at Kent in 1990 and is now in the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Pop, along with a group of subsequent paintings selected by Paul Schimmel for his seminal “Helter Skelter” exhibition of 1992, propelled Foulkes to new territory in his art-making, as well as new levels of national recognition.