Open Workspace and Place for Shaker Dances

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Wall of China the Great Wall of China Is 5,500Miles, 10,000 Li and Length Is 8,851.8Km

The Great Wall of China The Great Wall of China is 5,500miles, 10,000 Li and Length is 8,851.8km How they build the great wall is they use slaves,farmers,soldiers and common people. http://www.travelchinaguide.com/china_great_wall/facts/ The Great Wall is made between 1368-1644. The Great Wall of China is not the biggest wall,but is the longest. http://community.travelchinaguide.com/photo-album/show.asp?aid=2278 http://wiki.answers.com/Q/Is_the_Great_Wall_of_China_the_biggest_wall_in_the_world?#slide2 The Great Wall It said that there was million is so long that people were building the Great like a River. Wall and many of them lost their lives.There is even childrens had to be part of it. http://www.travelchinaguide.com/china_great_wall/construction/labor_force.htm The Great Wall is so long that over Qin Shi Huang 11 provinces and 58 cities. is the one who start the Great Wall who decide to Start the Great Wall. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Wall_of_China http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_many_cities_does_the_great_wall_of_china_go_through#slide2 http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_many_provinces_does_the_Great_Wall_of_China_go_through#slide2 Over Million people helped to build the Great Wall of China. The Great Wall is pretty old. http://facts.randomhistory.com/2009/04/18_great-wall.html There is more than one part of Great Wall There is five on the map of BeiJing When the Great Wall was build lots people don’t know where they need to go.Most of them lost their home and their part of Family. http://www.tour-beijing.com/great_wall/?gclid=CPeMlfXlm7sCFWJo7Aod- 3IAIA#.UqHditlkFxU The Great Wall is so long that is almost over all the states. -

FIGURE CONTENT Figure Page 2.1 Landscape of Luang Prabang

[6] FIGURE CONTENT Figure Page 2.1 Landscape of Luang Prabang…………………………………………………………………………………….7 2.2 Landscape of Luang Prabang (2)………………………………………………………………………………..8 2.3 A map showed the territory of Mainland Southeast Asian Kingdoms……………………11 2.4 Landscape of Bangkok……………………………………………………………………………………………….17 3.1 A figure illustrate the component of a Chedi………………………………………………………….25 3.2 A That at Wat Apai…………………………………………………………………………………………………….26 3.3 3 That Noi (ธาตุนอย) at Wat Maha That……………………………………………………………………26 3.4 That Luang, Vientiane……………………………………………………………………………………………….27 3.5 Pra That Bang Puen, Nong Kai, Thailand…………………………………………………………………28 3.6 A That at Wat Naga Yai, Vientiane……………………………………………………………………………28 3.7 Pra That Nong Sam Muen, Chaiyabhum, Thailand………………………………………………….28 3.8 Pra That Cheng Chum (พระธาตุเชิงชุม), Sakon Nakorn, Thailand…………………………….29 3.9 Pra That In Hang, Savannaket, Lao PDR…………………………………………………………………..29 3.10 That Phun, Xieng Kwang, Lao PDR………………………………………………………………………….30 3.11 A front side picture of Sim of Wat Xieng Thong, Luang Prabang…………………………30 3.12 A side plan of Wat Xieng Thong's sim……………………………………………………………………31 3.13 Sim of Wat Xieng Thong, Luang Prabang, Lao PDR……………………………………………….32 3.14 Sim of Wat Pak Kan, Luang Prabang, Lao PDR……………………………………………………….32 3.15 Sim of Wat Sisaket, Vientiane, Lao PDR………………………………………………………………….33 [7] 3.16 Sim of Wat Kiri, Luang Prabang, Lao PDR……………………………………………………………….34 3.17 Sim of Wat Mai, Luang Prabang, Lao PDR………………………………………………………………34 3.18 Sim of Wat Long Koon, Luang Prabang, -

GREAT WALL of CHINA Deconstructing

GREAT WALL OF CHINA Deconstructing History: Great Wall of China It took millennia to build, but today the Great Wall of China stands out as one of the world's most famous landmarks. Perhaps the most recognizable symbol of China and its long and vivid history, the Great Wall of China actually consists of numerous walls and fortifications, many running parallel to each other. Originally conceived by Emperor Qin Shi Huang (c. 259-210 B.C.) in the third century B.C. as a means of preventing incursions from barbarian nomads into the Chinese Empire, the wall is one of the most extensive construction projects ever completed… Though the Great Wall never effectively prevented invaders from entering China, it came to function more as a psychological barrier between Chinese civilization and the world, and remains a powerful symbol of the country’s enduring strength. QIN DYNASTY CONSTRUCTION Though the beginning of the Great Wall of China can be traced to the third century B.C., many of the fortifications included in the wall date from hundreds of years earlier, when China was divided into a number of individual kingdoms during the so-called Warring States Period. Around 220 B.C., Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a unified China, ordered that earlier fortifications between states be removed and a number of existing walls along the northern border be joined into a single system that would extend for more than 10,000 li (a li is about one-third of a mile) and protect China against attacks from the north. -

D. Listokin Resume

DAVID LISTOKIN RUTGERS, THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW JERSEY EDWARD J. BLOUSTEIN SCHOOL OF PLANNING AND PUBLIC POLICY (EJB) CENTER FOR URBAN POLICY RESEARCH (CUPR) EDUCATION Ph.D., Rutgers University, 1978 M.C.R.P., Rutgers University, 1971 M.P.A. Bernard Baruch College, 1976 B.A. Magna Cum Laude, Brooklyn College, 1970 AWARDS/SCHOLARSHIPS Educator of the Year Award—Urban Land Institute, New Jersey Chapter (2006) New Jersey Historic Preservation Award (1998) [from Historic Sites Council and State Historic Preservation Office] Fulbright Scholar Award, Council for International Exchange of Scholars (1994–95) Faculty Fellowship Mortgage Bankers Association (1976) Danforth Foundation, Kent Fellowship (1973) National Institute of Mental Health Fellow (1972) Phi Beta Kappa (1970) ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE RUTGERS UNIVERSITY School (EJB) Director of Student Assessment, 2013 to date School (EJB) Graduate and Doctoral Director, 2002 to 2009 CUPR Co-Director, 2000 to date Director, Institute for Meadowlands Studies, 2004 to date Professor II, July 1992 to date (Retitled 2013 to Distinguished Professor) Professor, July 1982 to July 1992 Associate Professor, July 1979 (tenured) to June 1982 Assistant Professor, July 1974 Research Associate, October 1971 HARVARD UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF DESIGN DEPARTMENT OF URBAN PLANNING AND DESIGN Visiting Professor, Fall 1996 – Fall 2000 CORNELL UNIVERSITY, COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE, ART, AND PLANNING DEPARTMENT OF CITY AND REGIONAL PLANNING Visiting Professor, Spring 2007, Spring 2004–05, Fall 2002 RESEARCH AND TEACHING SPECIALIZATION David Listokin is a leading authority on public finance, development impact analysis, and historic preservation. Dr. Listokin has recently been analyzing strategies to quantify the economic benefits of historic preservation, research sponsored by the federal government (National Park Service), state governments (e.g., Texas and Florida), and the National Trust for Historic Preservation. -

World Monuments Fund Names Jonathan S. Bell As Vice President of Programs

WORLD MONUMENTS FUND NAMES JONATHAN S. BELL AS VICE PRESIDENT OF PROGRAMS New York, NY, March 4, 2020– World Monuments Fund (WMF) today announced Jonathan S. Bell as its new Vice President of Programs. Dr. Bell will be the first individual to hold this newly created position. Since 1965, WMF has partnered with local stakeholders to safeguard more than 600 sites worldwide, including Angkor Archaeological Park in Siem Reap, Cambodia; the Forbidden City’s Qianlong Garden in Beijing, China; and Civil Rights sites across Alabama in the United States. Dr. Bell, who comes to the organization from the National Geographic Society, has spent over twenty years collaborating with national and local governments to develop conservation and management strategies for cultural heritage sites and infrastructure around the world. Over his career, he has worked with the Getty Conservation Institute on World Heritage Sites in China and Egypt, evaluated cultural site management from Kazakhstan to Colombia, and has overseen strategic planning for largescale flood infrastructure for the County of Los Angeles. Bell serves on multiple ICOMOS scientific committees as an expert member and sits on the Editorial Board of the Journal of Architectural Conservation. Currently, Dr. Bell serves as the Director of the Human Journey Initiative at National Geographic Society, where he oversees a portfolio of projects that highlight the origins of humankind and contribute to the protection of humanity’s legacy. In addition to working closely with some of the world’s leading paleoanthropologists and geneticists to further research on human origins, Bell has helped launch a new program focused on cultural heritage that will highlight the significance of historic sites and the threats they face for a broad public, while also contributing to local capacity-building in documentation and conservation approaches. -

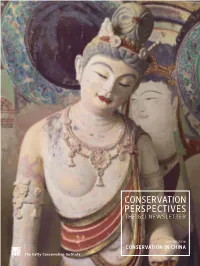

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

Portfolio Investment Opportunities in China Democratic Revolution in China, Was Launched There

Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Investment Strategy The Great Wall of China In c. 220 BC, under Qin Shihuangdi (first emperor of the Qin dynasty), sections of earlier fortifications were joined together to form a united system to repel invasions from the north. Construction of the Great Wall continued for more than 16 centuries, up to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), National Emblem of China creating the world's largest defense structure. Source: About.com, travelchinaguide.com. The design of the national emblem of the People's Republic of China shows Tiananmen under the light of five stars, and is framed with ears of grain and a cogwheel. Tiananmen is the symbol of modern China because the May 4th Movement of 1919, which marked the beginning of the new- Portfolio Investment Opportunities in China democratic revolution in China, was launched there. The meaning of the word David M. Darst, CFA Tiananmen is “Gate of Heavenly Succession.” On the emblem, the cogwheel and the ears of grain represent the working June 2011 class and the peasantry, respectively, and the five stars symbolize the solidarity of the various nationalities of China. The Han nationality makes up 92 percent of China’s total population, while the remaining eight percent are represented by over 50 nationalities, including: Mongol, Hui, Tibetan, Uygur, Miao, Yi, Zhuang, Bouyei, Korean, Manchu, Kazak, and Dai. Source: About.com, travelchinaguide.com. Please refer to important information, disclosures, and qualifications at the end of this material. Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Investment Strategy Table of Contents The Chinese Dynasties Section 1 Background Page 3 Length of Period Dynasty (or period) Extent of Period (Years) Section 2 Issues for Consideration Page 65 Xia c. -

Source of the Lake: 150 Years of History in Fond Du Lac

SOURCE OF THE LAKE: 150 YEARS OF HISTORY IN FOND DU LAC Clarence B. Davis, Ph.D., editor Action Printing, Fond du Lac, Wisconsin 1 Copyright © 2002 by Clarence B. Davis All Rights Reserved Printed by Action Printing, Fond du Lac, Wisconsin 2 For my students, past, present, and future, with gratitude. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS AND LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS PREFACE p. 7 Clarence B. Davis, Ph.D. SOCIETY AND CULTURE 1. Ceresco: Utopia in Fond du Lac County p. 11 Gayle A. Kiszely 2. Fond du Lac’s Black Community and Their Church, p. 33 1865-1943 Sally Albertz 3. The Temperance Movement in Fond du Lac, 1847-1878 p. 55 Kate G. Berres 4. One Community, One School: p. 71 One-Room Schools in Fond du Lac County Tracey Haegler and Sue Fellerer POLITICS 5. Fond du Lac’s Anti-La Follette Movement, 1900-1905 p. 91 Matthew J. Crane 6. “Tin Soldier:” Fond du Lac’s Courthouse Square p. 111 Union Soldiers Monument Ann Martin 7. Fond du Lac and the Election of 1920 p. 127 Jason Ehlert 8. Fond du Lac’s Forgotten Famous Son: F. Ryan Duffy p. 139 Edie Birschbach 9. The Brothertown Indians and American Indian Policy p. 165 Jason S. Walter 4 ECONOMY AND BUSINESS 10. Down the Not-So-Lazy River: Commercial Steamboats in the p. 181 Fox River Valley, 1843-1900 Timothy A. Casiana 11. Art and Commerce in Fond du Lac: Mark Robert Harrison, p. 199 1819-1894 Sonja J. Bolchen 12. A Grand Scheme on the Grand River: p. -

SELECTED ARTICLES of INTEREST in RECENT VOLUMES of the AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK American Jewish Fiction Turns Inward, Sylvia Ba

SELECTED ARTICLES OF INTEREST IN RECENT VOLUMES OF THE AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK American Jewish Fiction Turns Inward, Sylvia Barack Fishman 1960-1990 91:35-69 American Jewish Museums: Trends and Issues Ruth R. Seldin 91:71-113 Anti-Semitism in Europe Since the Holocaust Robert S. Wistrich 93:3-23 Counting Jewish Populations: Methods and Paul Ritterband, Barry A. Problems Kosmin, and Jeffrey Scheckner 88:204-221 Current Trends in American Jewish Jack Wertheimer 97:3-92 Philanthropy Ethiopian Jews in Israel Steven Kaplan and Chaim Rosen 94:59-109 Ethnic Differences Among Israeli Jews: A New U.O. Schmelz, Sergio Look DellaPergola, and Uri Avner 90:3-204 Herzl's Road to Zionism Shlomo Avineri 98:3-15 The Impact of Feminism on American Jewish Sylvia B. Fishman 89:3-62 Life Israel at 50: An American Perspective Arnold M. Eisen 98:47-71 Israel at 50: An Israeli Perspective Yossi Klein Halevi 98:25-46 Israeli Literature and the American Reader Alan Mintz 97:93-114 Israelis in the United States Steven J. Gold and Bruce A. Phillips 96:51-101 Jewish Experience on Film—An American Joel Rosenberg 96:3-50 Overview Jewish Identity in Conversionary and Mixed Peter Y. Medding, Gary A. Marriages Tobin, Sylvia Barack Fishman, and Mordechai Rimor 92:3-76 719 720 / AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK, 1999 Jewish Organizational Life in the Jack Wertheimer 95:3-98 United States Since 1945 Jewish Theology in North America: Arnold Eisen 91:3-33 Notes on Two Decades Jews in the European Community: Sergio DellaPergola 93:25-82 Sociodemographic Trends and Challenges New Perspectives in American Jewish Nathan Glazer 87:3-19 Sociology The Population of Reunited Jerusalem, U.O. -

European Military Heritage and Water Engineering Past

EUROPEAN MILITARY HERITAGE AND WATER ENGINEERING PAST AND PRESENT Prof.dr. Piet Lombaerde (UA) INTRODUCTION What tell us the engineers in their tracts about fortification and water? SIMON STEVIN (1548-1620) Nieuwe maniere van stercktebou door Spilsluysen, Leiden, 1617 ADAM FREITAG (1602-1664) Architectura Militaris Nova et aucta, Oder Newe vermehrte Fortification , Leiden, 1631. Model of a fortified city near a river The city of Sluis with its fortifications, 1604 The ‘Schencenschans’ fortress on the Rhine River (Kleef, Germany) MENNO VAN COEHOORN (1641-1704) Nieuwe Vestingbouw op een natte of lage Horisont, Leeuwarden, 1702 SÉBASTIEN LE PRESTRE DE VAUBAN (1633-1707) Damme, 1702 Fort Lupin (Charante Maritime) JAN BLANKEN (1755-1838) Verhandeling over het aanleggen en maaken Van zogenaamde drooge dokken in de Hollandsche Zeehavens…, 1796. The dry docks of Hellevoetsluis (The Netherlands) TYPOLOGY • The Moats as Defence System: - Motte & Bailey Castles - Water Castles - Medieval Walled Cities - Bastioned Cities • Rings of Moats as Defence Systems • The Sea as Defence System • The Inundations as Ultimate Defence System • Naval bases THE MOATS AS DEFENCE SYSTEM Motte & Bailey Castles: Motte ‘De Hoge Wal’ at Ertvelde (Flanders) The Water Castle of Wijnendale (Flanders, near Torhout): a medieval castle surrounded by a moat Cittadella: a medieval walled city in the province of Padua (Northern Italy), 13th century. Gravelines: a bastioned city by Vauban Westerlo (Brabant) Siege of the ‘castellum in fortezza’ of Drainage of the water from the Count de Merode by Count Charles de moat of the fortification to the river Mansfeld, 1583. Siege of Mariembourg August 9th 1554 Italian engineer Mario Brunelli Plan to ‘drawn’ the besieged city by the construction of a dam over the river dam (drawing by B. -

Luoyang Tour

www.lilysunchinatours.com 3 Days Xian -Luoyang Tour Basics Tour Code: LCT-XL-3D-01 Duration: 3 days Attractions: Terracotta Warriors and Horses Museum, Traditional Cave Dwelling, City Wall, Hanyangling Museum, Big Wild Goose Pagoda, Bell Tower, Great Mosque, Muslim Quarter, Longmen Grottoes, Shaolin Temple Overview: Both Xi'an and Luoyang belong to China's seven great ancient capital cities and are noted for places of historical interest such as the Terracotta Warriors Museum, the Shaolin Monastery and the Longmen Caves. As the Shaolin Martial Arts have inspired people worldwide, it’s something you definitely won’t miss during your trip. In addition, we will lead you to explore Xi'an in a different way by tasting the local food in the evening, learning calligraphy in a tranquil place. Highlights See the Terracotta Warriors and Horses which have been buried for thousands of years; Taste authentic local food; Ride a bike on the City Wall; Travel on a Chinese high-speed train; Be amazed by the famous Longmen Grottoes; Learn about the Martial Arts in the Shaolin Temple. Itinerary Date Starting Time Destination Day 1 9:00 a.m Terracotta Warriors Museum, Traditional Cave Tel: +86 18629295068 1 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] www.lilysunchinatours.com Dwelling, City Wall, Shuyuanmen Street Day 2 6:30 a.m Longmen Grottoes, Shaolin Temple Day 3 9:00 a.m Hanyangling Museum, Big Wild Goose Pagoda, Bell Tower, Muslim Quarter Day 1: Terracotta Warriors Museum, Traditional Cave Dwelling, City Wall, Shuyuanmen Street 09:00: Your friendly tour guide will meet you at your hotel lobby 09:50 - 12:30: Your three day heritage tour begins with the most significant sight - the Terracotta Warriors Museum. -

Summer 2016 Cultural Trip in Xi'an (Group 2)

Summer 2016 Cultural Trip in Xi’An (Group 2) July 2 2 -24, 2016 Table of Contents I. Itinerary II. What to Bring III. What to Expect Hotel location & contact information Destination Information • Big Wild Goose Pagoda • Museum of the Terra Cotta Army • Huaqing Hot Springs • Bell Tower and Drum Tower • Shaanxi History Museum Safety in the Xi’An • Most commonly encountered crimes and scams - Tea Scam - Art House scam - Beggars & garbage collectors • Passport and cash safety • Avoiding “black cabs” and other taxi safety IV. Emergency Information Staff and Tour Guide Contact Emergency Facility Locations 1 I. ITINERARY Please note: Schedule intended for general reference only; activities may be subject to change. Please note that you should bring or plan for all meals with an asterisk. Friday, July 22 Morning Group 2 10:00 Pick up at Jinqiao Residence Hall *Breakfast on your own (on the bus)! 13:30 Plane Departs Shanghai Pudong Airport Afternoon 16:15 Arrive at Xianyang Airport, then get on a bus to Hotel Evening Free time. Suggest visiting the Drum and Bell Tower, and the Muslim Quarter (15-minute walk from Hotel) Saturday, July 23 Morning 07:00 Breakfast at hotel 08:00 Visit Big Wild Goose Pagoda 10:00 Depart for Lintong 11:00 *Lunch on your own Afternoon 12:30 Visit the Huaqing Hot Springs 14:30 Visit the Terra Cotta Army 17:00 Return to Xi’An Evening 18:00 Dinner 19:00 Bus to Hotel Sunday, July 24 Morning 07:00 Breakfast at hotel, Check out 08:00 Depart for Shaanxi History Museum 09:00 Visit Shaanxi History Museum 11:30 Bus to Xianyang Airport Afternoon 12:30 *Lunch on your own (at Xianyang Airport) Group 2 15:00 Plane departs Xianyang Airport Evening 17:15 Arrive at Pudong Airport 18:00 Bus to Jinqiao Residence Hall 2 II.