The Impressionistic Guitar Is There a Mutual Influence Between the Spanish Guitar and the Impressionist Masters?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhythmic Foundation and Accompaniment

Introduction To Flamenco: Rhythmic Foundation and Accompaniment by "Flamenco Chuck" Keyser P.O. Box 1292 Santa Barbara, CA 93102 [email protected] http://users.aol.com/BuleriaChk/private/flamenco.html © Charles H. Keyser, Jr. 1993 (Painting by Rowan Hughes) Flamenco Philosophy IA My own view of Flamenco is that it is an artistic expression of an intense awareness of the existential human condition. It is an effort to come to terms with the concept that we are all "strangers and afraid, in a world we never made"; that there is probably no higher being, and that even if there is he/she (or it) is irrelevant to the human condition in the final analysis. The truth in Flamenco is that life must be lived and death must be faced on an individual basis; that it is the fundamental responsibility of each man and woman to come to terms with their own alienation with courage, dignity and humor, and to support others in their efforts. It is an excruciatingly honest art form. For flamencos it is this ever-present consciousness of death that gives life itself its meaning; not only as in the tragedy of a child's death from hunger in a far-off land or a senseless drive-by shooting in a big city, but even more fundamentally in death as a consequence of life itself, and the value that must be placed on life at each moment and on each human being at each point in their journey through it. And it is the intensity of this awareness that gave the Gypsy artists their power of expression. -

A Comparison of the Piano and Guitar Versions of Isaac Albéniz's Spanish Suite Op

A COMPARISON OF THE PIANO AND GUITAR VERSIONS OF ISAAC ALBÉNIZ'S SPANISH SUITE OP. 47 by YI-YIN CHIEN A LECTURE-DOCUMENT Presented to the School of Music and Dance of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts November 2016 2 “A Comparison of the Piano and Guitar Versions of Isaac Albéniz’s Spanish Suite, Op. 47’’ a document prepared by Yi-Yin Chien in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance. This document has been approved and accepted by: Jack Boss, Chair of the Examining Committee Date: November 20th, 2016 Committee in Charge: Dr. Jack Boss, Chair Dr. Juan Eduardo Wolf Dr. Dean Kramer Accepted by: Director of Graduate Studies, School of Music and Dance © 2016 Yi-Yin Chien 3 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME OF AUTHOR: Yi-Yin Chien PLACE OF BIRTH: Taiwan DATE OF BIRTH: November 02, 1986 GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOLS ATTENDED: University of Oregon, School of Music and Dance Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University Tainan National University of Arts DEGREES AWARDED: Doctor of Musical Arts, 2016, University of Oregon Master of Music, 2011, Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University Bachelor of Music, 2009, Tainan National University of Arts AREAS OF SPECIAL INTEREST: Piano Pedagogy Music Theory PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: College Piano Teaching, University of Oregon, School of Music and Dance, 09/2014 - 06/2015 Taught piano lessons for music major and non-major college students Graduate Teaching -

Against Expression?: Avant-Garde Aesthetics in Satie's" Parade"

Against Expression?: Avant-garde Aesthetics in Satie’s Parade A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2020 By Carissa Pitkin Cox 1705 Manchester Street Richland, WA 99352 [email protected] B.A. Whitman College, 2005 M.M. The Boston Conservatory, 2007 Committee Chair: Dr. Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract The 1918 ballet, Parade, and its music by Erik Satie is a fascinating, and historically significant example of the avant-garde, yet it has not received full attention in the field of musicology. This thesis will provide a study of Parade and the avant-garde, and specifically discuss the ways in which the avant-garde creates a dialectic between the expressiveness of the artwork and the listener’s emotional response. Because it explores the traditional boundaries of art, the avant-garde often resides outside the normal vein of aesthetic theoretical inquiry. However, expression theories can be effectively used to elucidate the aesthetics at play in Parade as well as the implications for expressability present in this avant-garde work. The expression theory of Jenefer Robinson allows for the distinction between expression and evocation (emotions evoked in the listener), and between the composer’s aesthetical goal and the listener’s reaction to an artwork. This has an ideal application in avant-garde works, because it is here that these two categories manifest themselves as so grossly disparate. -

1J131J Alexander Boggs Ryan,, Jr., B

omit THE PIANO STYLE OF CLAUDE DEBUSSY THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC by 1J131J Alexander Boggs Ryan,, Jr., B. M. Longview, Texas June, 1951 19139 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . , . iv Chapter I. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PIANO AS AN INFLUENCE ON STYLE . , . , . , . , . , . ., , , 1 II. DEBUSSY'S GENERAL MUSICAL STYLE . IS Melody Harmony Non--Harmonic Tones Rhythm III. INFLUENCES ON DEBUSSY'S PIANO WORKS . 56 APPENDIX (CHRONOLOGICAL LIST 0F DEBUSSY'S COMPLETE WORKS FOR PIANO) . , , 9 9 0 , 0 , 9 , , 9 ,9 71 BIBLIOGRAPHY *0 * * 0* '. * 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 .9 76 111 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Range of the piano . 2 2. Range of Beethoven Sonata 10, No.*. 3 . 9 3. Range of Beethoven Sonata .2. 111 . , . 9 4. Beethoven PR. 110, first movement, mm, 25-27 . 10 5. Chopin Nocturne in D Flat,._. 27,, No. 2 . 11 6. Field Nocturne No. 5 in B FlatMjodr . #.. 12 7. Chopin Nocturne,-Pp. 32, No. 2 . 13 8. Chopin Andante Spianato,,O . 22, mm. 41-42 . 13 9. An example of "thick technique" as found in the Chopin Fantaisie in F minor, 2. 49, mm. 99-101 -0 --9 -- 0 - 0 - .0 .. 0 . 15 10. Debussy Clair de lune, mm. 1-4. 23 11. Chopin Berceuse, OR. 51, mm. 1-4 . 24 12., Debussy La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune, mm. 32-34 . 25 13, Wagner Tristan und Isolde, Prelude to Act I, . -

Liner Notes (PDF)

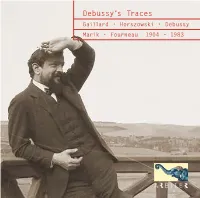

Debussy’s Traces Gaillard • Horszowski • Debussy Marik • Fourneau 1904 – 1983 Debussy’s Traces: Marius François Gaillard, CD II: Marik, Ranck, Horszowski, Garden, Debussy, Fourneau 1. Preludes, Book I: La Cathédrale engloutie 4:55 2. Preludes, Book I: Minstrels 1:57 CD I: 3. Preludes, Book II: La puerta del Vino 3:10 Marius-François Gaillard: 4. Preludes, Book II: Général Lavine 2:13 1. Valse Romantique 3:30 5. Preludes, Book II: Ondine 3:03 2. Arabesque no. 1 3:00 6. Preludes, Book II Homage à S. Pickwick, Esq. 2:39 3. Arabesque no. 2 2:34 7. Estampes: Pagodes 3:56 4. Ballade 5:20 8. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 4:49 5. Mazurka 2:52 Irén Marik: 6. Suite Bergamasque: Prélude 3:31 9. Preludes, Book I: Des pas sur la neige 3:10 7. Suite Bergamasque: Menuet 4:53 10. Preludes, Book II: Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses 8. Suite Bergamasque: Clair de lune 4:07 3:03 9. Pour le Piano: Prélude 3:47 Mieczysław Horszowski: Childrens Corner Suite: 10. Pour le Piano: Sarabande 5:08 11. Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum 2:48 11. Pour le Piano: Toccata 3:53 12. Jimbo’s lullaby 3:16 12. Masques 5:15 13 Serenade of the Doll 2:52 13. Estampes: Pagodes 3:49 14. The snow is dancing 3:01 14. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 3:53 15. The little Shepherd 2:16 15. Estampes: Jardins sous la pluie 3:27 16. Golliwog’s Cake walk 3:07 16. Images, Book I: Reflets dans l’eau 4:01 Mary Garden & Claude Debussy: Ariettes oubliées: 17. -

Electrophonic Musical Instruments

G10H CPC COOPERATIVE PATENT CLASSIFICATION G PHYSICS (NOTES omitted) INSTRUMENTS G10 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS; ACOUSTICS (NOTES omitted) G10H ELECTROPHONIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS (electronic circuits in general H03) NOTE This subclass covers musical instruments in which individual notes are constituted as electric oscillations under the control of a performer and the oscillations are converted to sound-vibrations by a loud-speaker or equivalent instrument. WARNING In this subclass non-limiting references (in the sense of paragraph 39 of the Guide to the IPC) may still be displayed in the scheme. 1/00 Details of electrophonic musical instruments 1/053 . during execution only {(voice controlled (keyboards applicable also to other musical instruments G10H 5/005)} instruments G10B, G10C; arrangements for producing 1/0535 . {by switches incorporating a mechanical a reverberation or echo sound G10K 15/08) vibrator, the envelope of the mechanical 1/0008 . {Associated control or indicating means (teaching vibration being used as modulating signal} of music per se G09B 15/00)} 1/055 . by switches with variable impedance 1/0016 . {Means for indicating which keys, frets or strings elements are to be actuated, e.g. using lights or leds} 1/0551 . {using variable capacitors} 1/0025 . {Automatic or semi-automatic music 1/0553 . {using optical or light-responsive means} composition, e.g. producing random music, 1/0555 . {using magnetic or electromagnetic applying rules from music theory or modifying a means} musical piece (automatically producing a series of 1/0556 . {using piezo-electric means} tones G10H 1/26)} 1/0558 . {using variable resistors} 1/0033 . {Recording/reproducing or transmission of 1/057 . by envelope-forming circuits music for electrophonic musical instruments (of 1/0575 . -

Classical Guitar Music by Irish Composers: Performing Editions and Critical Commentary

L , - 0 * 3 7 * 7 w NUI MAYNOOTH OII» c d I »■ f£ir*«nn WA Huad Classical Guitar Music by Irish Composers: Performing Editions and Critical Commentary John J. Feeley Thesis submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth as fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music (Performance) 3 Volumes Volume 1: Text Department of Music NUI Maynooth Head of Department: Professor Gerard Gillen Supervisor: Dr. Barra Boydell May 2007 VOLUME 1 CONTENTS ABSTRACT i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 13 APPROACHES TO GUITAR COMPOSITION BY IRISH COMPOSERS Historical overview of the guitar repertoire 13 Approaches to guitar composition by Irish composers ! 6 CHAPTER 2 31 DETAILED DISCUSSION OF SEVEN SELECTED WORKS Brent Parker, Concertino No. I for Guitar, Strings and Percussion 31 Editorial Commentary 43 Jane O'Leary, Duo for Alto Flute and Guitar 52 Editorial Commentary 69 Jerome de Bromhead, Gemini 70 Editorial Commentary 77 John Buckley, Guitar Sonata No. 2 80 Editorial Commentary 97 Mary Kelly, Shard 98 Editorial Commentary 104 CONTENTS CONT’D John McLachlan, Four pieces for Guitar 107 Editorial Commentary 121 David Fennessy, ...sting like a bee 123 Editorial Commentary 134 CHAPTER 3 135 CONCERTOS Brent Parker Concertino No. 2 for Guitar and Strings 135 Editorial Commentary 142 Jerome de Bromhead, Concerto for Guitar and Strings 148 Editorial Commentary 152 Eric Sweeney, Concerto for Guitar and Strings 154 Editorial Commentary 161 CHAPTER 4 164 DUOS Seoirse Bodley Zeiten des Jahres for soprano and guitar 164 Editorial -

Rippling Notes” to the Federal Way Performing Arts & Event Center Sunday, September 17 at 3:00 Pm

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT August 23, 2017 Scott Abts Marketing Coordinator [email protected] DOWNLOAD IMAGES & VIDEO HERE 253-835-7022 MASTSER TIMPLE MUSICIAN GERMÁN LÓPEZ BRINGS “RIPPLING NOTES” TO THE FEDERAL WAY PERFORMING ARTS & EVENT CENTER SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 17 AT 3:00 PM The Performing Arts & Event Center of Federal Way welcomes Germán (Pronounced: Herman) López, Sunday, September 17 at 3:00 PM. On stage with guitarist Antonio Toledo, Germán harnesses the grit of Spanish flamenco, the structure of West African rhythms, the flourishing spirit of jazz, and an innovative 21st century approach to performing “island music.” His principal instrument is one of the grandfathers of the ‘ukelele’, and part of the same instrumental family that includes the cavaquinho, the cuatro and the charango. Germán López’s music has been praised for “entrancing” performances of “delicately rippling notes” (Huffington Post), notes that flow from musical traditions uniting Spain, Africa, and the New World. The “timple” is a diminutive 5 stringed instrument intrinsic to music of the Canary Islands. Of all the hypotheses that exist about the origin of the “timple”, the most widely accepted is that it descends from the European baroque guitar, smaller than the classical guitar, and with five strings. Tickets for Germán López are on sale now at www.fwpaec.org or by calling 2535-835-7010. The Performing Arts and Event Center is located at 31510 Pete von Reichbauer Way South, Federal Way, WA 98003. We’ll see you at the show! About the PAEC The Performing Arts & Event Center opened August of 2017 as the South King County premier center for entertainment in the region. -

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism" Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)! Biographical sketch:! §" Born in St. Petersburg, Russia.! §" Studied composition with “Mighty Russian Five” composer Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov.! §" Emigrated to Switzerland (1910) and France (1920) before settling in the United States during WW II (1939). ! §" Along with Arnold Schönberg, generally considered the most important composer of the first half or the 20th century.! §" Works generally divided into three style periods:! •" “Russian” Period (c.1907-1918), including “primitivist” works! •" Neoclassical Period (c.1922-1952)! •" Serialist Period (c.1952-1971)! §" Died in New York City in 1971.! Pablo Picasso: Portrait of Igor Stravinsky (1920)! Ballets Russes" History:! §" Founded in 1909 by impresario Serge Diaghilev.! §" The original company was active until Diaghilev’s death in 1929.! §" In addition to choreographing works by established composers (Tschaikowsky, Rimsky- Korsakov, Borodin, Schumann), commissioned important new works by Debussy, Satie, Ravel, Prokofiev, Poulenc, and Stravinsky.! §" Stravinsky composed three of his most famous and important works for the Ballets Russes: L’Oiseau de Feu (Firebird, 1910), Petrouchka (1911), and Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913).! §" Flamboyant dancer/choreographer Vaclav Nijinsky was an important collaborator during the early years of the troupe.! ! Serge Diaghilev (1872-1929) ! Ballets Russes" Serge Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky.! Stravinsky with Vaclav Nijinsky as Petrouchka (Paris, 1911).! Ballets -

Negotiating the Self Through Flamenco Dance

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Anthropology Theses Department of Anthropology 12-2009 Embodied Identities: Negotiating the Self through Flamenco Dance Pamela Ann Caltabiano Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/anthro_theses Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Caltabiano, Pamela Ann, "Embodied Identities: Negotiating the Self through Flamenco Dance." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/anthro_theses/33 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Anthropology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMBODIED IDENTITIES: NEGOTIATING THE SELF THROUGH FLAMENCO DANCE by PAMELA ANN CALTABIANO Under the Direction of Emanuela Guano ABSTRACT Drawing on ethnographic research conducted in Atlanta, this study analyzes how transnational practices of, and discourse about, flamenco dance contribute to the performance and embodiment of gender, ethnic, and national identities. It argues that, in the context of the flamenco studio, women dancers renegotiate authenticity and hybridity against the backdrop of an embodied “exot- ic” passion. INDEX WORDS: Gender, Dance, Flamenco, Identity, Exoticism, Embodiment, Performance EMBODIED IDENTITIES: NEGOTIATING THE SELF THROUGH FLAMENCO DANCE by PAMELA ANN -

Claude Debussy Orchestral Works Dirk Altmann · Daniel Gauthier Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart Des SWR · Heinz Holliger 02 CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862 – 1918) 03

Claude Debussy Orchestral Works Dirk Altmann · Daniel Gauthier Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart des SWR · Heinz Holliger 02 CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862 – 1918) 03 1 Première Rapsodie pour orchestre 7 Prélude à L’après-midi d’un faune [11:35] Diese wesensmäßige Fertigkeit hatte schon in den Chemie“, an der er sich selbst immer neu ergötzen avec clarinette principale [08:15] flûte solo: Tatjana Ruhland frühen Neunzigern die Bedenken des Dichters konnte, und die aus sich selbst erwachsenden For- Stéphane Mallarmé zerstreut, der zunächst von men in Regelwerke zu zwängen, sich im Geflecht Images pour orchestre 8 Rapsodie pour Debussys Ansinnen, die Ekloge vom Après-midi des Gefundenen, bereits „Gehabten“ zu verhed- Deutsch 2 Rondes de Printemps [08:29] orchestre et saxophone [09:45] d’un faune mit Musik zu umgeben, nicht begeis- dern. Vielleicht wurde daher auch nur das Prélude 3 Gigues [08:38] tert war. Er fürchtete eine bloße „Verdopplung“ zum „Faun“ vollendet, während das Interlude und Iberia [19:48] TOTAL TIME [67:04] seiner musikalisch-erotischen Alexandriner, sah die abschließende Paraphrase nie über die Idee 4 I. Par les rues et par les chemins [07:09] sich aber, kaum dass er das Resultat zu hören be- hinausgelangten. Es war schon alles gesagt. 5 II. Les parfums de la nuit [08:10] 1 Dirk Altmann Klarinette | clarinet kam, ebenso bezwungen wie die Besucher der 6 III. Le matin d'un jour de fête [04:28] 8 Daniel Gauthier Saxophon | saxophone Société Nationale, die am 22. Dezember 1894 die Wer weiß, ob nicht aus just diesem Grunde auch Uraufführung des Prélude „zum Nachmittag eines die Rapsodie arabe im Sande verlief, die sich der Fauns“ miterleben durften. -

Four-Hand Piano Music • 2

DEBUSSY Four-Hand Piano Music • 2 Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un faune La Mer • Images Jean-Pierre Armengaud Olivier Chauzu Claude Debussy (1862–1918) undulating arabesques complemented by an expressive Written between 1905 and December 1908, Ibéria was Music for Piano Four Hands • 2 theme which is followed by a new, melancholy figure treated the first of the Images to be completed. Debussyʼs only visit contrapuntally in the upper register; the second is to Spain consisted of a single afternoon spent in San Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarméʼs eclogue, or pastoral is impassioned, almost Wagnerian in tone. The central dominated by dotted rhythms and sees the reappearance Sebastián, just across the border. There are no quotations poem, LʼAprès-midi dʼun faune (The Afternoon of the Faun; section introduces the third theme, which is marked of the cyclical theme. The music then becomes more or borrowings from pre-existing music here, the work pub. 1876) was quick to capture the imagination of expressif et très soutenu and wreathed in arabesques, serene, ending with a solemn, chorale-like theme. drawing instead on a kind of imagined folk tradition in which Debussy, who even gave a copy of its second edition to triplets and arpeggios. Jeux de vagues (Play of the waves) acts as the scherzo all the melodies stem from the composerʼs own mind, fellow composer Paul Dukas in May 1887. Mallarmé, who in This arrangement was made by Ravel in early 1910, in here, with a central episode whose main function is that of although they are based on modal or ornamental cellular 1885 had written a prose article entitled Richard Wagner, response to a commission from the publisher Fromont.