New Thought History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ew Kenyon and the Twelve

CHRISTIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE PO Box 8500, Charlotte, NC 28271 Feature Article: JAW755-1 WHAT'S WRONG WITH THE FAITH MOVEMENT (PART ONE): E. W. KENYON AND THE TWELVE APOSTLES OF ANOTHER GOSPEL by Hank Hanegraaff This article first appeared in the Christian Research Journal, volume 15, number 3 (1993). For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal go to: http://www.equip.org SYNOPSIS What's wrong with the "Faith" movement? Its leaders include many of the most popular television evangelists. Its adherents compose a large percentage of charismatic evangelical Christians. Its emphases on faith, the authority of the believer, and the absolute veracity of Scripture could appear to be just what today's church needs. And yet, I am convinced that this movement poses one of the greatest contemporary threats to orthodox Christianity from within. Through it, cultic theology is being increasingly accepted as true Christianity. This article will highlight several serious problems with the Faith movement by providing an overview of its major sources and leaders. Part Two will focus on the movement's doctrinal deviations as represented by one of its leading proponents.1 ITS DEBT TO NEW THOUGHT It is important to note at the outset that the bulk of Faith theology can be traced directly to the cultic teachings of New Thought metaphysics. Thus, much of the theology of the Faith movement can also be found in such clearly pseudo-Christian cults as Religious Science, Christian Science, and the Unity School of Christianity. Over a -

Science and Spirituality As Applied to OD: the Unique Christian Science Perspective: a Qualitative Research Study

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2020 Science and spirituality as applied to OD: the unique Christian Science perspective: a qualitative research study Charlotte Booth [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Part of the Organization Development Commons Recommended Citation Booth, Charlotte, "Science and spirituality as applied to OD: the unique Christian Science perspective: a qualitative research study" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 1156. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/1156 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. SCIENCE AND SPIRITUALITY AS APPLIED TO OD: THE UNIQUE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE PERSPECTIVE A QUALITATIVE RESEARCH STUDY ____________________________________ A Research Project Presented to the Faculty of The Graziadio Business School Pepperdine University ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science In Organization Development ____________________________________ by Charlotte Booth July 2020 © 2020 Charlotte Booth This research project, completed by CHARLOTTE BOOTH under the guidance of the Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to -

List of New Thought Periodicals Compiled by Rev

List of New Thought Periodicals compiled by Rev. Lynne Hollander, 2003 Source Title Place Publisher How often Dates Founding Editor or Editor or notes Key to worksheet Source: A = Archives, B = Braden's book, L = Library of Congress If title is bold, the Archives holds at least one issue A Abundant Living San Diego, CA Abundant Living Foundation Monthly 1964-1988 Jack Addington A Abundant Living Prescott, AZ Delia Sellers, Ministries, Inc. Monthly 1995-2015 Delia Sellers A Act Today Johannesburg, So. Africa Association of Creative Monthly John P. Cutmore Thought A Active Creative Thought Johannesburg, So. Africa Association of Creative Bi-monthly Mrs. Rea Kotze Thought A, B Active Service London Society for Spreading the Varies Weekly in Fnded and Edited by Frank Knowledge of True Prayer 1916, monthly L. Rawson (SSKTP), Crystal Press since 1940 A, B Advanced Thought Journal Chicago, IL Advanced Thought Monthly 1916-24 Edited by W.W. Atkinson Publishing A Affirmation Texas Church of Today - Divine Bi-monthly Anne Kunath Science A, B Affirmer, The - A Pocket Sydney, N.S.W., Australia New Thought Center Monthly 1927- Miss Grace Aguilar, monthly, Magazine of Inspiration, 2/1932=Vol.5 #1 Health & Happiness A All Seeing Eye, The Los Angeles, CA Hall Publishing Monthly M.M. Saxton, Manly Palmer Hall L American New Life Holyoke, MA W.E. Towne Quarterly W.E. Towne (referenced in Nautilus 6/1914) A American Theosophist, The Wheaton, IL American Theosophist Monthly Scott Minors, absorbed by Quest A Anchors of Truth Penn Yan, NY Truth Activities Weekly 1951-1953 Charlton L. -

New Fuller Ebook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms

New Fuller eBook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms. Peggy Helmerick Publication Title eISBN Handbook of Cities and the Environment 9781784712266 Handbook of US–China Relations 9781784715731 Handbook on Gender and War 9781849808927 Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science 9781784710828 Anti-Corruption Strategies in Fragile States 9781784719715 Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality 9781785367267 Politics of Persuasion, The 9781782546702 Individualism and Inequality 9781784716516 Handbook on Migration and Social Policy 9781783476299 Global Regionalisms and Higher Education 9781784712358 Handbook of Migration and Health 9781784714789 Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting 9781784715922 Trust, Social Capital and the Scandinavian Welfare State 9781785365584 Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Forest Conservation and Climate Change 9781784716608 Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime 9781783476237 Cities as Political Objects 9781784719906 Leadership Imagination, The 9781785361395 Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact 9781784711856 Rise of the Hybrid Domain, The 9781785360435 Public Utilities, Second Edition 9781785365539 Challenges of Collaboration in Environmental Governance, The 9781785360411 Ethics, Environmental Justice and Climate Change 9781785367601 Politics and Policy of Wellbeing, The 9781783479337 Handbook on Theories of Governance 9781782548508 Neoliberal Capitalism and Precarious Work 9781781954959 Political Entrepreneurship 9781785363504 Handbook on Gender and Health 9781784710866 Linking -

Leibniz on Consciousness and Self-Consciousness Rocco J

Leibniz on Consciousness and Self-Consciousness Rocco J. Gennaro [Final version in NEW ESSAYS ON THE RATIONALISTS, Oxford U Press, 1999] In this paper I discuss the so-called "higher-order thought theory of consciousness" (the HOT theory) with special attention to how Leibnizian theses can help support it and how it can shed light on Leibniz's theory of perception, apperception, and consciousness. It will become clear how treating Leibniz as a HOT theorist can solve some of the problems he faced and some of the puzzles posed by commentators, e.g. animal mentality and the role of reason and memory in self-consciousness. I do not hold Leibniz's metaphysic of immaterial simple substances (i.e. monads), but even a contemporary materialist can learn a great deal from him. 1. What is the HOT Theory? In the absence of any plausible reductionist account of consciousness in nonmentalistic terms, the HOT theory says that the best explanation for what makes a mental state conscious is that it is accompanied by a thought (or awareness) that one is in that state.1 The sense of 'conscious state' I have in mind is the same as Nagel's sense, i.e. there is 'something it is like to be in that state' from a subjective or first-person point of view.2 Now, when the conscious mental state is a first-order world-directed state the HOT is not itself conscious; otherwise, circularity and an infinite regress would follow. Moreover, when the higher-order thought (HOT) is itself conscious, there is a yet higher-order (or third-order) thought directed at the second-order state. -

The 10 Core Concepts of Science of Mind Dr. Ernest Holmes, The

The 10 Core Concepts of Science of Mind Dr. Ernest Holmes, the founder of Religious Science and developer of the Science of Mind philosophy, gave this definition for his teaching: Religious Science is a synthesis of the laws of science, opinions of philosophy, and revelations of religion, applied to human needs and the aspirations of humankind. Dr. Ernest Holmes was a mystic who found God in the silence. Going within and experiencing God in the deepest part of himself was his spiritual practice. His spirituality was reflected in his living; he believed he was one with God, and he experienced that oneness in all that he did. As important as the mystical experience was to Dr. Holmes, he also believed that religion had to be applied to everyday life problems, as an integral part of the walk of faith. Wholeness involved the Presence, yes, but also the Power -- the two faces of the dual nature of God. Dr. Holmes developed the Science of Mind philosophy to reflect his twin beliefs that the inner experience of God gave entry to the Power of God and that changing the way we think about our conditions causes the Power of the Universe to change those conditions to make our lives better. Science of Mind identifies the spiritual principles that apply equally to everyone in every situation, and it teaches us how to use them for our advantage. In their 1993 revision of the Foundational Class curriculum, Religious Science educators demonstrated that the Science of Mind philosophy is based on 10 Core Concepts that serve as the organizing principles of the Universe. -

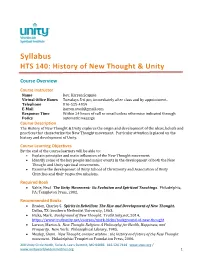

HTS 140: History of New Thought & Unity

Syllabus HTS 140: History of New Thought & Unity Course Overview Course Instructor Name Rev. Karren Scapple Virtual Office Hours Tuesdays 5-6 pm, immediately after class and by appointment. Telephone 816-525-4059 E-Mail [email protected] Response Time Within 24 hours of call or email unless otherwise indicated through Policy automatic message Course Description The History of New Thought & Unity explores the origin and development of the ideas, beliefs and practices that characterize the New Thought movement. Particular attention is placed on the history and development of Unity. Course Learning Objectives By the end of the course learners will be able to: • Explain principles and main influences of the New Thought movement. • Identify some of the key people and major events in the development of both the New Thought and Unity spiritual movements. • Examine the development of Unity School of Christianity and Association of Unity Churches and their respective missions. Required Book • Vahle, Neal. The Unity Movement: Its Evolution and Spiritual Teachings. Philadelphia, PA: Templeton Press, 2002. Recommended Books • Braden, Charles S. Spirits in Rebellion: The Rise and Development of New Thought. Dallas, TX: Southern Methodist University, 1963. • Hicks, Mark. Background of New Thought. TruthUnity.net, 2014. https://www.truthunity.net/courses/mark-hicks/background-of-new-thought • Larson, Martin A. New Thought Religion: A Philosophy for Health, Happiness, and Prosperity. New York: Philosophical Library, 1985. • Mosley, Glenn. New Thought, ancient wisdom : the history and future of the New Thought movement. Philadelphia: Templeton Foundation Press, 2006. 200 Unity Circle North, Suite A, Lee’s Summit, MO 64086 816.524.7414 www.uwsi.org / www.unityworldwideministries.org 1 • Shepherd, Thomas. -

What Is Science of Mind Or Religious Science?

AFSI Class Lecture 2015 What is Science of Mind or Religious Science? The simple answer to the question, (the one I can give you in 10 minutes) can be found in Wikipedia. It says: “Science of Mind was established in 1927 by Ernest Holmes (1887–1960) and is a spiritual, philosophical and metaphysical religious movement within the New Thought movement. In general, the term "Science of Mind" applies to the teachings, while the term "Religious Science" applies to the organizations. However, adherents often use the terms interchangeably. In his book, The Science of Mind, Ernest Holmes stated "Religious Science is a correlation of laws of science, opinions of philosophy, and revelations of religion applied to human needs and the aspirations of man." He also stated that Religious Science/Science of Mind (RS/SOM) is not based on any "authority" of established beliefs, but rather on "what it can accomplish" for the people who practice it.” This last statement is a very important one. Science of Mind is, above all else, a practice that is designed to produce tangible results in the lives of its adherents. Wikipedia lists 12 beliefs and 10 core concepts and I shall spare you the reading of them! Instead I shall attempt to summarize this Spiritual practice in this way: 1. The mind of God is always of the Good. 2. Your life results, flow from your mind aligned or misaligned with this Good. This requires learning new ways of thinking. This is why Science of Mind organizations see themselves as “Centers” of learning. The phenomenon called “The Secret” and ideas like the Law of Attraction from the teachings of Abraham / Hicks, find an enthusiastic audience in these Centers. -

Spirit Speaks January-February 2014 Volume 11 Issue 1

Spirit Speaks January-February 2014 Volume 11 Issue 1 Honoring Presence ~ Nurturing Spirit ~ . ~ Enriching the lives of all we serve Dr. Moira’s Message Dear Ones, A NEW Year! Such a gift! Not all of us were given it in 2014. Many of us saw the transition of loved ones in 2013 and are adjusting to a new reality without them. I know however, that their last gift to us is a reminder to get our house in order, so that when the moment of our own transition arises, we are ready to move into it in grace, peace and joy, and with a sense of accomplishment. Recently, I read somewhere, “So many people complain that there is never enough time and yet they live as though they had all the time in the world.” I am still pondering the insightfulness of these words. When I preside over memo- rial services, I remind us all that whatever it is we have put aside, on the back burner until later, our passed loved ones are saying to us on their departure: “What are you waiting for? When do you think you’ll have enough time to take care of these things? What if you run out of time? Bring these things forward now. Whatever needs mending, fixing, healing and releasing, take care of it now!” The only right time to take care of anything is NOW. This is a great time of year to decide to work on that list of back burner things, and one by one take care of them. -

Esoteric Christianity and Mental Therapeutics

ESOTERIC CHRISTIANITY .A.:IID MENTAL THERAPEUTICS. BY W. F. EVANS, A'OTBoB o-r "DI~ LAw o-r CUBII" .uro "PBnliTIVB MIND.CUBJI," " We speak wisdom among the perfect : yet a wisdom not of this age, nor of the rulers of this age, which are coming to nought." ·• -I Cor. ii : 6. BOSTON: H. H. CARTER & KARRICK, PUBLISHERS, s BE.A.CON STREET. 1886. Digit, zed by Goog le Entered, according to tbe Act of Congreea, In tbe year 1886, by W. F. EVANS, In tbe 011lce of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. J . S. CusmNo &: Co., PRINTJCRB, BosTON. ~. .. Digit• zed by Goog le PREFACE. Tms volume is designed to complete a series of works on the subject of Mental Therapeutics, the publication of which was commenced several years ago, and which was intended to give a view of the subject in its various aspects. It is hoped the book may be found ac<'eptable and useful to those who are interested in the subject of which it treats. It contains a series of twelve lessons or lectures, which the author has given in a private way to a number of persons who were desirous of learning something of the philosophy and practice of the phrenopathic method of cure. In order that the information contained in the lectures might become more generally circulated, and meet the demands for instruc tion that are made upon the author, they are committed to the press. There is given in the brief compass of the volume a plain presentation of the principles that underlie the practice of the mental system of healing, so that any person of ordinary intelligence, who is moved by a desire to do good, may make a trial of those directions. -

Christianity and Theosophy

Christianity and Theosophy “Theosophy is an Eastern religion, isn’t it—sort of like Hinduism or Buddhism?” That question is wrong in two important ways. First, Theosophy is not a religion at all, but a way of viewing human nature and the world that is compatible with the nondogmatic aspects of any religion. Second, Theosophy is no more Eastern than it is Western—it seeks for what is in common to all cultures and religions and attempts to complement East and West with each other. Theosophists belong to many different religions: among them, Buddhism, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, Islam, Judaism, and Christianity; and within Christianity to churches such as the Catholic, Methodist, Baptist, Episcopalian, Presbyterian, and many others. Theosophy presents the wisdom of the West to the East and the wisdom of the East to the West. Theosophy within Christianity The word Theosophy, meaning “divine wisdom,” designates an ancient outlook that recognizes within the many outward forms of religion an inner core shared by all of them. Theosophy and Christianity agree in their essence. Christianity provides a unique way of expressing the Wisdom Tradition of Theosophy, and Theosophy can enrich an understanding of the inner side of the Christian Way. The New Testament itself frequently alludes to profound religious truths lying underneath the outer words of the biblical text. Frequently we come across such passages as “I speak God’s hidden wisdom.” We read that some things are beyond human comprehension, but “these it is that God has revealed to us through the Spirit” (1 Corinthians 2:7-10). The Apostle Paul goes on to tell recently converted Christians that he is unable to impart such wisdom because “indeed, you are still not ready for it, for you are still on the merely natural plane” (1 Corinthians 3:2). -

Gurdjieff Beyond the Personality Cult: Reading the Work and Its Re-Workings Notes on René Zuber’S ‘Who Are You Monsieur Gurdjieff?’

Religion and the Arts 21 (2017) 176–188 RELIGION and the ARTS brill.com/rart Gurdjieff beyond the Personality Cult: Reading the Work and Its Re-Workings Notes on René Zuber’s ‘Who are You Monsieur Gurdjieff?’ Vrasidas Karalis The University of Sydney Abstract This article is a philosophical, aesthetic, and existential exploration of a small book written by one of Gurdjieff’s disciples, René Zuber (1902–1979), under the title Qui êtes-vous Monsieur Gurdjieff? (Le Courrier du Livre, 1977, éditions Éoliennes, 1997 and in English, translated by Jenny Koralek, Arkana, 1980). Formally the book belongs to a hybrid genre mixing autobiography, philosophy, religious reflection, memoir, and essay. It was composed by Zuber in order to interpret and contextualize Gurdjieff’s teaching and presence particularly during the last years of his life in Paris. At the core of the narrative rests the strange, tense, and somehow ambivalent relationship between Zuber and Gurdjieff, a relationship of equal admiration and reservation, in an attempt, after the death of the master, to establish the proper intellectual and phenomenological locus for Gurdjieff’s work. Keywords G. I. Gurdjieff – esoteric Christianity – René Zuber i Introduction According to all the information we possess from various memoirs and autobi- ographical accounts, it is obvious that encountering G. I. Gurdjieff must have been quite an arduous and frustrating experience. Even for the people who admired him, such as the architect Frank Lloyd Wright or indeed like P. D. Ous- pensky himself, the relationship with the “Master” must have been full of unin- tended consequences. It seems that Gurdjieff overwhelmed his students with © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2017 | doi: 10.1163/15685292-02101007 Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 11:59:58PM via free access gurdjieff beyond the personality cult 177 the force of his personality, the aura of his presence, and the immediacy of his teachings.