Key Social, Psychological, Ethical, and Design Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Close Engagements with Artificial Companions: Key Social, Psychological, Ethical and Design Issues

OII / e-Horizons Forum Discussion Paper No. 14, January 2008 Close Engagements with Artificial Companions: Key Social, Psychological, Ethical and Design Issues by Malcolm Peltu Oxford Internet Institute Yorick Wilks Oxford Internet Institute OII / e-Horizons Forum Discussion Paper No. 14 Oxford Internet Institute University of Oxford 1 St Giles, Oxford OX1 3JS United Kingdom Forum Discussion Paper January 2008 © University of Oxford for the Oxford Internet Institute 2008 Close Engagements with Artificial Companions Foreword This paper summarizes discussions at the multidisciplinary forum1 held at the University of Oxford on 26 October 2007 entitled Artificial Companions in Society: Perspectives on the Present and Future, as well as an open meeting the previous day addressed by Sherry Turkle2. The event was organized by Yorick Wilks, Senior Research Fellow for the Oxford Internet Institute (OII)3, on behalf of the e-Horizons Institute4 and in association with the EU Integrated Project COMPANIONS. COMPANIONS is studying conversational software-based artificial agents that will get to know their owners over a substantial period. These could be developed to advise, comfort and carry out a wide range of functions to support diverse personal and social needs, such as to be ‘artificial companions’ for the elderly, helping their owners to learn, or assisting to sustain their owners’ fitness and health. The invited forum participants, including computer and social scientists, also discussed a range of related developments that use advanced artificial intelligence and human– computer interaction approaches. They examined key issues in building artificial companions, emphasizing their social, personal, emotional and ethical implications. This paper summarizes the main issues raised. -

Customized Book List Linguistics

ABCD springer.com Springer Customized Book List Linguistics FRANKFURT BOOKFAIR 2007 springer.com/booksellers Linguistics 1 K. Ahmad, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland; C. Brewster, University K. Ahmad, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland; C. Brewster, University E. Alcón Soler, Universitat Jaume I, Spain; M.P. Safont Jordà, Uni- of Sheffield, UK; M. Stevenson, University of Sheffield, UK (Eds.) of Sheffield, UK; M. Stevenson, University of Sheffield, UK (Eds.) versitat Jaume I, Spain (Eds.) Words and Intelligence I Words and Intelligence II Intercultural Language Use and Selected Papers by Yorick Wilks Essays in Honor of Yorick Wilks Language Learning Yorick Wilks is a central figure in the fields of Natu- Yorick Wilks is a central figure in the fields of Natu- This volume attempts to address an issue that de- ral Language Processing and Artificial Intelligence. ral Language Processing and Artificial Intelligence. serves further attention on the part of language ac- His influence extends to many areas and includes His influence has extends to many areas of these quisition researchers: that of intercultural learners contributions to Machines Translation, word sense fields and includes contributions to Machine Trans- in instructed language contexts. Given the fact that disambiguation, dialogue modeling and Information lation, word sense disambiguation, dialogue mod- most speech communities where such learning takes Extraction. This book celebrates the work of Yorick eling and Information Extraction. This book cele- place are at least bilingual, and the idea that English Wilks in the form of a selection of his papers which brates the work of Yorick Wilks from the perspective is studied for the purposes of communication among are intended to reflect the range and depth of his of his peers. -

ACL Lifetime Achievement Award: on Whose Shoulders?

ACL Lifetime Achievement Award On Whose Shoulders? Yorick Wilks∗ University of Sheffield Introduction The title of this piece refers to Newton’s only known modest remark: “If I have seen farther than other men, it was because I was standing on the shoulders of giants.” Since he himself was so much greater than his predecessors, he was in fact standing on the shoulders of dwarfs, a much less attractive metaphor. I intend no comparisons with Newton in what follows: NLP/CL has no Newtons and no Nobel Prizes so far, and quite rightly. I intend only to draw attention to a tendency in our field to ignore its intellectual inheritance and debt; I intend to discharge a little of this debt in this article, partly as an encouragement to others to improve our lack of scholarship and knowledge of our own roots, often driven by the desire for novelty and to name our own systems. Roger Schank used to argue that it was crucial to name your own NLP system and then have lots of students to colonize all major CS departments, although time has not been kind to his many achievements and originalities, even though he did build just such an Empire. But to me one of the most striking losses from our corporate memory is the man who is to me the greatest of the first generation and still with us: Vic Yngve. This is the man who gave us COMIT, the first NLP programming language; the first random generation of sentences; and the first direct link from syntactic structure to parsing processes and storage (the depth hypothesis). -

The Future of Computational Linguistics: on Beyond Alchemy

REVIEW published: 19 April 2021 doi: 10.3389/frai.2021.625341 The Future of Computational Linguistics: On Beyond Alchemy Kenneth Church 1* and Mark Liberman 2 1Baidu Research, Sunnyvale, CA, United States, 2University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States Over the decades, fashions in Computational Linguistics have changed again and again, with major shifts in motivations, methods and applications. When digital computers first appeared, linguistic analysis adopted the new methods of information theory, which accorded well with the ideas that dominated psychology and philosophy. Then came formal language theory and the idea of AI as applied logic, in sync with the development of cognitive science. That was followed by a revival of 1950s-style empiricism—AI as applied statistics—which in turn was followed by the age of deep nets. There are signs that the climate is changing again, and we offer some thoughts about paths forward, especially for younger researchers who will soon be the leaders. Keywords: empiricism, rationalism, deep nets, logic, probability, connectionism, computational linguistics, alchemy Edited by: 1 INTRODUCTION: BETTER TOGETHER Sergei Nirenburg, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, We are going to speculate about the future of Computational Linguistics (CL)—how things may United States change, how we think things should change, and our view of the forces that will determine what Reviewed by: actually happens. Given that different people have different views of what the field is, and even what Yorick Wilks, it should be called, we will define the field of Computational Linguistics by what is discussed in top Florida Institute for Human and venues, using Google Scholar’s ranking of venues.1 The name of one of these venues, the Association Machine Cognition, United States Tony Veale, for Computational Linguistics (ACL), was controversial in the 1960s. -

Selected Papers of Margaret Masterman

Language, cohesion and form: Selected papers of Margaret Masterman Edited, with an introduction and commentaries by Yorick Wilks Preface This book is a posthumous tribute to Margaret Masterman and the influence of her ideas and life on the development of the processing of language by computers, a part of what would now be called artificial intelligence. During her lifetime she did not publish a book, and this volume is intended to remedy that by reprinting some of her most influential papers, many of which never went beyond research memoranda from the Cambridge Language Research Unit, which she founded and which became a major centre in that field. However, the style in which she wrote, and the originality of the structures she presented as the basis of language processing by machine, now require some commentary and explanation in places if they are to be accessible today, most particularly by relating them to more recent and more widely publicised work where closely related concepts occur. In this volume, eleven of Margaret Masterman's papers are grouped by topic, and in a general order reflecting their intellectual development. Three are accompanied by a commentary by the editor where this was thought helpful plus a fourth with a commentary by Karen Sparck Jones, which she wrote when reissuing that particular paper and which is used by permission. The themes of the papers recur and some of the commentaries touch on the content of a number of the papers. The papers present problems of style and notation for the reader: some readers may be deterred by the notation used here and by the complexity of some of the diagrams, but they should not be, since the message of the papers, about the nature of language and computation, is to a large degree independent these. -

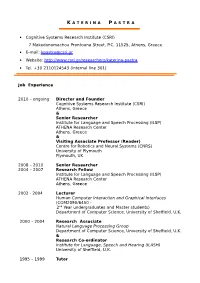

E K a T E R I N I P a S T

K A T E R I N A P A S T R A Cognitive Systems Research Institute (CSRI) 7 Makedonomachou Prantouna Street, P.C. 11525, Athens, Greece E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.csri.gr/researchers/katerina-pastra Tel. +30 2110124543 (internal line 301) Job Experience 2010 – ongoing Director and Founder Cognitive Systems Research Institute (CSRI) Athens, Greece & Senior Researcher Institute for Language and Speech Processing (ILSP) ATHENA Research Center Athens, Greece & Visiting Associate Professor (Reader) Centre for Robotics and Neural Systems (CNRS) University of Plymouth Plymouth, UK 2008 – 2010 Senior Researcher 2004 – 2007 Research Fellow Institute for Language and Speech Processing (ILSP) ATHENA Research Center Athens, Greece 2002 - 2004 Lecturer Human Computer Interaction and Graphical Interfaces (COM2090/6450 - 2nd Year undergraduates and Master students) Department of Computer Science, University of Sheffield, U.K. 2000 – 2004 Research Associate Natural Language Processing Group Department of Computer Science, University of Sheffield, U.K. & Research Co-ordinator Institute for Language, Speech and Hearing (ILASH) University of Sheffield, U.K. 1995 – 1999 Tutor Curriculum Vitae: Katerina Pastra Private tutorials in Ancient Greek, Modern Greek and English, to high-school students Research Projects 2017–2020 RoboCom++ Rethinking robotics for the robot companion of the future FLAG-ERA Joint Transnational Research https://www.flagera.eu/funded-projects/ Duties: CSRI PI 2014–2018 iV&L Network The European Network on Integrating -

Statistical Language Modeling

STATISTICAL LANGUAGE MODELING UNIVERSITAT¨ DES SAARLANDES La th´eoriedes probabilit´esn’est, au fond, que le bon sens r´eduitau calcul. Probability theory is nothing but common sense reduced to calculation. –Pierre-Simon Laplace, 1812 Winter Semester 2014/2015 Mondays 12:00–14:00, Starting 27 Oct. 2014 Place: 2.11 Geb. C7.2 Instructor Dr. Jon Dehdari Office DFKI: 1.11 Gebaude¨ D3.1; FR4.6: 1.15 Gebaude¨ A2.2 Office Hours By appointment Email jon.dehdari at dfki.d_e Website jon.dehdari.org/teaching/uds/lm 1 Overview / Uberblick¨ Statistical language modeling, which provides probabilities for linguistic ut- terances, is a vital component in machine translation, automatic speech recog- nition, information retrieval, and many other language technologies. In this seminar we will discuss different types of language models and how they are used in various applications. The language models include n-gram- (includ- ing various smoothing techniques), skip-, class-, factored-, topic-, maxent-, and neural-network-based approaches. We also will look at how these perform on different language typologies and at different scales of training set sizes. This seminar will be followed at the end of the Winter Semester by a short project (seminar) where you will work in small groups to identify a shortcom- ing of an existing language model, make a novel modification to overcome the shortcoming, compare experimental results of your new method with the exist- ing baseline, and discuss the results. It’ll be fun. 1 2 Tentative Schedule / Vorlaufiger¨ Terminplan Date Topic Presenter(in) Q’s Datum Thema Fragen Mo, 20 Oct. -

An Announcement and a Call

The FINITE STRING Newsletter Announcements Announcements Lecture topics will include computer vision, compu- tational linguistics, expert systems, robotics, AI pro- gramming languages, hardware for AI, and psychologi- Computer Modeling of Linguistic Theory: cal modelling. Late-night programming classes will be An Announcement and a Call for Papers conducted for novices with little or no programming The ACL is sponsoring three sessions on experience, and experts who wish to extend their LISP "Computer Modeling of Linguistic Theory" in con- or PROLOG skills. There will be a set of workshops junction with the Annual Meeting of the Linguistic for industrial participants focussing on case studies of Society of America which will be held in New York AI applications. A parallel series of workshops on City at the Grand Hyatt Hotel, December 28-30, research methods will cover experimental design, paper 1981. and thesis writing, and seminar presentation skills. The specific objective is to address a number of For further information, contact: ideas -- some old, some new -- that have been gain- Mrs. Olwyn Wilson ing the attention of both theoretical and computational AISB School Administrator linguists alike. These ideas include new models for Institute of Educational Technology grammars and new strategies for parsing, motivated by Open University the goal of relating grammatical competence and per- Walton Hall formance in a principled way. People from both lin- Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, ENGLAND guistics and computational linguistics are becoming conversant with augmented transition networks, lexical NATO Symposium on Artificial functional grammars, phrase structure grammars, Mo- and Human Intelligence ntague grammars, and transformational grammars, and beginning to explore their implications for each other. -

Machine Conversations the Kluwer International Series in Engineering and Computer Science Machine Conversations

MACHINE CONVERSATIONS THE KLUWER INTERNATIONAL SERIES IN ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER SCIENCE MACHINE CONVERSATIONS edited by Yorick Wilks University of Sheffield United Kingdom SPRINGER SCIENCE+BUSINESS MEDIA, LLC Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Machine conversations I edited by Yorick Wilks. p. em. -- (Kluwer international series in engineering and computer science ; SECS 511) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4419-5092-5 ISBN 978-1-4757-5687-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4757-5687-6 1. Human-computer interaction. 2. Natural language processing (Computer science) 3. Artificial intelligence. I. Wilks, Yorick, 1939- . II. Series. QA76.9.H85M33 1999 004' .01 '9--dc21 99-30264 CIP Copyright® 1999 by Springer Science+Business Media New York Originally published by Kluwer Academic Publishers in 1999 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photo copying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. Printed on acid-free paper. Contents Preface vii 1 Dialogue Programs I have Known and Loved Over 33 Years 1 K.M. Colby 2 Comments on Human-Computer Conversation 5 K.M. Colby 3 Human-Computer Conversation in A Cognitive Therapy Prog~m 9 K.M.Colby 4 Architectural Considerations for Conversational Systems 21 G. Gorz, J. Spilker, V. Strom and H. Weber 5 Conversational Multimedia Interaction 35 M.T. Maybury 6 The SpeakEasy Dialogue Controller 47 G. Ball 7 Choosing a Response Using Problem Solving Plans and Rhetorical Relations 57 P. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 0521454891 - Language, Cohesion and Form Margaret Masterman and Yorick Wilks Frontmatter More information Language, Cohesion and Form Margaret Masterman was a pioneer in the field of computational linguis- tics. Working in the earliest days of language processing by computer, she believed that meaning, not grammar, was the key to understanding languages, and that machines could determine the meaning of sentences. She was able, even on simple machines, to undertake sophisticated experiments in machine translation, and carried out important work on the use of semantic codings and thesauri to determine the meaning structure of text. This volume brings together Masterman’s groundbreak- ing papers for the first time. Through his insightful commentaries, Yorick Wilks argues that Masterman came close to developing a computational theory of language meaning based on the ideas of Wittgenstein, and shows the importance of her work in the philosophy of science and the nature of iconic languages. Of key interest in computational linguistics and artificial intelligence, this book will remind scholars of Masterman’s significant contribution to the field. Permission to publish Margaret Masterman’s work was granted to Yorick Wilks by the Cambridge Language Research Unit. YORICK WILKS is Professor in the Department of Computer Science, University of Sheffield, and Director of ILASH, the Institute of Language, Speech and Hearing. A leading scholar in the field of compu- tational linguistics, he has published numerous articles and sixbooks in the area of artificial intelligence, the most recent being Electric Words: Dictionaries, Computers and Meanings (with Brian Slator and Louise Guthrie, 1996). He designed CONVERSE, the dialogue system that won the Loebner prize in New York in 1998. -

June 1973 June 1975

teixfiff J?^ V5l Artificial IntelligenceLaboratory, STANFORD UNIVERSITY, Stanford, California 94305 Telephone 415-321-2300, ext. 4202 28 February 1974 Director, Advanced Research Projects Agency Department of Defense Washington, D. C. ÜBJECT: Quarterly Management Report Form approved, Budget Bureau No. 22-R0293. IRPA Order Number: 2494 Contract Number: DAHCIS 73C 0435 'rogiam Code Number: 3D30 Principal Investigator: Prof. John McCarthy 415-321-2300, extension 4430 Jame of Contractor: Board of Trustees of Executive Officer: Lester Earnest the Leland Stanford Junior University 415-321-2300, extension 4202 Iffective Date of Contract: 15 June 1973 Short Title of Work: Artificial Intelligence, Heuristic Programming, and Contract Expiration Date: 30 June 1975 Network Protocols Projects .mount of Contract: $3,000,000 )ear Sir: During the Autumn Quarter, members of our staff published several articles on analysis of algorithms and programming languages [1, 12, 14, 15]. An article on computer vision appeared [2], as well as a report on our robotics work [13]. A Ph.D. dissertation on mathematical theory of computation was produced [11] and Manna completed the first textbook in this field, which will appear shortly [3]. Several articles [4, 8, 9, 10] and a book [5] on natural language understanding were published by our staff. The Heuristic Programming Project published two more articles on chemical inference [6, 7]. Research Program and Plan In late October, we learned of the prospective availability of a BBN Pager at NASA Ames. Since the A. I. Project wished to change to the Tenex operating system, we requested and received approval to have the pager. It was moved here and installed over the Christmas holidays. -

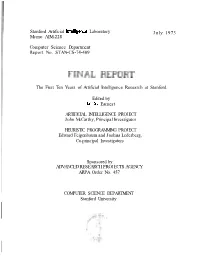

Stanford Artificial Tnteliigence Laboratory Memo AIM-228

Stanford Artificial tnteliigence Laboratory July 1973 Memo AIM-228 Computer Science Department Report No. STAN-CS-74-409 The First Ten Years of Artificial Intelligence Research at Stanford Edited by Lester Earnest ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE PROJECT John McCarthy, Principal Investigator HEURISTIC PROGRAMMING PROJECT Edward Feigenbaum and Joshua Lederberg, Co-principal Investigators Sponsored by ADVANCED RESEARCH PROJECTS AGENCY ARPA Order No. 457 COMPUTER SCIENCE DEPARTMENT Stanford University Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory July 1973 tYlerno AIM-228 Computer Science Department Report No. STAN-CS-74-409 The First Ten Years of Artificial Intelligence Research at Stanford Edited by - Lester Earnest ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE PROJECT John McCarthy, Principal Investigator HEURISTIC PROGRAMMING PROJECT Edward Feigenbaum and Joshua Lederberg, CoAprincipal Investigators ABSTRACT The first ten years of research in artificial intelligence and related fields at Stanford University have yielded significant results in computer vision and control of manipulators, speech recognition, heuristic programming, representation theory, mathematical theory of computation, and modeling of organic chemical processes. This report summarizes the accomplishments and provides bibliographies in each research area. This research runs supported by the Advanced Research Projects Agency of the Department of Defense under Contract SD-153. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing