Challenging Ethnocracy in Tel Aviv-Jaffa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’S First Decades

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’s First Decades Rotem Erez June 7th, 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Stefan Kipfer A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Student Signature: _____________________ Supervisor Signature:_____________________ Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................6 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................9 Chapter 1: A Comparative Study of the Early Years of Colonial Casablanca and Tel-Aviv ..................... 19 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 19 Historical Background ............................................................................................................................ -

Rates, Indications, and Speech Perception Outcomes of Revision Cochlear Implantations

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Rates, Indications, and Speech Perception Outcomes of Revision Cochlear Implantations Doron Sagiv 1,2,*,†,‡, Yifat Yaar-Soffer 3,4,‡, Ziva Yakir 3, Yael Henkin 3,4 and Yisgav Shapira 1,2 1 Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer 5262100, Israel; [email protected] 2 Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv City 6997801, Israel 3 Hearing, Speech, and Language Center, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer 5262100, Israel; [email protected] (Y.Y.-S.); [email protected] (Z.Y.); [email protected] (Y.H.) 4 Department of Communication Disorders, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv City 6997801, Israel * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +972-35-302-242; Fax: +972-35-305-387 † Present address: Department of Oolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, University of California Davis, Sacramento, CA 95817, USA. ‡ Sagiv and Yaar-Soffer contributed equally to this study and should be considered joint first author. Abstract: Revision cochlear implant (RCI) is a growing burden on cochlear implant programs. While reports on RCI rate are frequent, outcome measures are limited. The objectives of the current study were to: (1) evaluate RCI rate, (2) classify indications, (3) delineate the pre-RCI clinical course, and (4) measure surgical and speech perception outcomes, in a large cohort of patients implanted in a tertiary referral center between 1989–2018. Retrospective data review was performed and included patient demographics, medical records, and audiologic outcomes. Results indicated that RCI rate Citation: Sagiv, D.; Yaar-Soffer, Y.; was 11.7% (172/1465), with a trend of increased RCI load over the years. -

Women's Israel Trip ITINERARY

ITINERARY The Cohen Camps’ Women’s Trip to Israel Led by Adina Cohen April 10-22, 2018 Tuesday April 10 DEPARTURE Departure from Boston (own arrangements) Wednesday April 11 BRUCHIM HABA’AIM-WELCOME TO ISRAEL! . Rendezvous at Ben Gurion airport at 14:10 (or at hotel in Tel Aviv) . Opening Program at the Port of Jaffa, where pilgrims and olim entered the Holy Land for centuries. Welcome Dinner at Café Yafo . Check-in at hotel Overnight: Carlton, Tel Aviv Thursday April 12 A LIGHT UNTO THE NATIONS . Torah Yoga Session . Visit Save a Child’s Heart-a project of Wolfston Hospital, in which Israeli pediatric surgeons provide pro-bono cardiac surery for children from all over Africa and the Middle East. “Shuk Bites” lunch in the Old Jaffa Flea Market . Visit “The Women’s Courtyard” – a designer outlet empowering Arab and Jewish local women . Israeli Folk Dancing interactive program- Follow the beat of Israeli women throughout history and culture and experience Israel’s transformation through dance. Enjoy dinner at the “Liliot” Restaurant, which employs youth at risk. Overnight: Carlton, Tel Aviv Friday April 13 COSMOPOLITAN TEL AVIV . Interactive movement & drum circle workshop with Batya . “Shuk & Cook” program with lunch at the Carmel Market . Stroll through the Nahalat Binyamin weekly arts & crafts fair . Time at leisure to prepare for Shabbat . Candle lighting Cohen Camps Women’s Trip to Israel 2018 Revised 22 Aug 17 Page 1 of 4 . Join Israelis for a unique, musical “Kabbalat Shabbat” with Bet Tefilah Hayisraeli, a liberal, independent, and egalitarian community in Tel Aviv, which is committed to Jewish spirit, culture, and social action. -

HOUSTON REAL ESTATE MISSION to ISRAEL March 3-9, 2018

Program dated: May 24, 2017 HOUSTON REAL ESTATE MISSION TO ISRAEL March 3-9, 2018 D a y O n e : Saturday, March 3, 2018 DEPARTURE . Depart the U.S.A. Overnight: Flight D a y T w o : Sunday, March 4, 2018 TLV 24/7 . 12:00 p.m. Meet your tour educator in the hotel lobby. Enjoy lunch at Blue Sky, with it’s a wide selection of fish, vegetables, olive oil and artisan cheese, accompanied with local wines and overlooking the stunning views of the Mediterranean Sea. A Look into Our Journey: Tour orientation with the Mission Chair and the tour educator. The Booming Tel Aviv Real Estate Market: Take a tour of various locations around Tel Aviv with Ilan Pivko, a leading Israeli Architect and entrepreneur. Return to the hotel. Cocktails overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. Combining Business Abroad and Real Estate in Israel: Dinner at 2C with Danna Azrieli, the Acting Chairman of The Azrieli Group, at the Azrieli Towers. Overnight: Tel Aviv D a y T h r e e : Monday, March 5, 2018 FROM RED ROOFTOPS TO HIGH-RISERS . The Laws of Urban Development in Israel: Private breakfast at the hotel with Dr. Efrat Tolkowsky, CEO of the Gazit-Globe Real Estate Institute at IDC. Stroll down Rothschild Boulevard to view examples of the intriguing Bauhaus-style architecture from the 1930s; the local proliferation of the style won Tel Aviv recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage site and the nickname of ‘the White City'. Explore the commercial and residential developments with Dr. Micha Gross, the head of the Tel Aviv Bauhaus Center. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

Zefat, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century C.E. Epitaphs from the Jewish Cemetery

1 In loving memory of my mother, Batsheva Friedman Stepansky, whose forefathers arrived in Zefat and Tiberias 200 years ago and are buried in their ancient cemeteries Zefat, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century C.E. Epitaphs from the Jewish Cemetery Yosef Stepansky, Zefat Introduction In recent years a large concentration of gravestones bearing Hebrew epitaphs from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries C.E. has been exposed in the ancient cemetery of Zefat, among them the gravestones of prominent Rabbis, Torah Academy and community leaders, well-known women (such as Rachel Ha-Ashkenazit Iberlin and Donia Reyna, the sister of Rabbi Chaim Vital), the disciples of Rabbi Isaac Luria ("Ha-ARI"), as well as several until-now unknown personalities. Some of the gravestones are of famous Rabbis and personalities whose bones were brought to Israel from abroad, several of which belong to the well-known Nassi and Benvenisti families, possibly relatives of Dona Gracia. To date (2018) some fifty gravestones (some only partially preserved) have been exposed, and that is so far the largest group of ancient Hebrew epitaphs that may be observed insitu at one site in Israel. Stylistically similar epitaphs can be found in the Jewish cemeteries in Istanbul (Kushta) and Salonika, the two largest and most important Jewish centers in the Ottoman Empire during that time. Fig. 1: The ancient cemetery in Zefat, general view, facing north; the bottom of the picture is the southern, most ancient part of the cemetery. 2 Since 2010 the southernmost part of the old cemetery of Zefat (Fig. 1; map ref. 24615/76365), seemingly the most ancient part of the cemetery, has been scrutinized in order to document and organize the information inscribed on the oldest of the gravestones found in this area, in wake of and parallel with cleaning-up and preservation work conducted in this area under the auspices of the Zefat religious council. -

An Urban Miracle Geddes @ Tel Aviv the Single Success of Modern Planning Editor: Thom Rofe Designed by the Author

NAHOUM COHEN ARCHITECT & TOWN PLANNER AN URBAN MIRACLE GEDDES @ TEL AVIV THE SINGLE SUCCESS OF MODERN PLANNING EDITOR: THOM ROFE DESIGNED BY THE AUTHOR WWW.NAHOUMCOHEN.WORDPRESS.COM ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY THE AUTHOR WRITTEN AND PUBLISHED BY THE KIND ASSISTANCE OT THE TEL AVIV MUNICIPALITY NOTE: THE COMPLETE BOOK WILL BE SENT IN PDF FORM ON DEMAND BY EMAIL TO - N. COHEN : [email protected] 1 NAHOUM COHEN architect & town planner AN URBAN MIRACLE GEDDES @ TEL AVIV 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART ONE INTRODUCTION 11 PART TWO THE SETTING 34 PART THREE THE PLAN 67 3 PART FOUR THE PRESENT 143 PART FIVE THE FUTURE 195 ADDENDA GEDDES@TEL AVIV 4 In loving memory of my parents, Louisa and Nissim Cohen Designed by the Author Printed in Israel 5 INTRODUCTION & FOREWORD 6 Foreword The purpose of this book is twofold. First, it aims to make known to the general public the fact that Tel Aviv, a modern town one hundred years of age, is in its core one of the few successes of modern planning. Tel Aviv enjoys real urban activity, almost around the clock, and this activity contains all the range of human achievement: social, cultural, financial, etc. This intensity is promoted and enlivened by a relatively minor part of the city, the part planned by Sir Patrick Geddes, a Scotsman, anthropologist and man of vision. This urban core is the subject of the book, and it will be explored and presented here using aerial photos, maps, panoramic views, and what we hope will be layman-accessible explanations. -

Free WALKING Tours

With the citywide bike-sharing system, the galleries, restaurants, parks, With 14 kilometers of white sandy beach, 300 days of sunshine a markets and the beach are all within a few minutes from wherever you year and a vibrant, Mediterranean atmosphere, Tel Aviv is known for are. Tel Aviv is the ultimate urban vacation. The city boasts some of FREE its welcoming, friendly and liberal vibe. The city is a fusion of old and the world's best city beaches, a dynamic cultural scene, a world-class The City of Tel Aviv-Yafo offers four free walking new, combining one of the world's most innovative business scenes international airport and a wide range of accommodation facilities, WALKING tours in English. The tours cover the White City, Old alongside the oldest functioning port in the world. Tel Aviv is a center from luxury beachfront hotels to intimate boutique properties. Tel Aviv Jaffa (based on tips), Tel Aviv by Night and Tel Aviv of the arts, with world-renowned museums and hundreds of small is just a short drive from the holy sites of Jerusalem and the Galilee, as TOURS University. There is no need to book in advance galleries. The 'White City', Tel Aviv’s architecturally unique core, was well as the Dead Sea. Tel Aviv is an excellent conference destination, VISIT designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Hosting more than 60 cultural with its top of the line infrastructure, the Israel Trade Fairs & Convention events across the city every day, a world-renowned nightlife scene and WHITE CITY Center and year-round Mediterranean weather. -

Tel Aviv Elite Guide to Tel Aviv

DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES TEL AVIV ELITE GUIDE TO TEL AVIV HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV 3 ONLY ELITE 4 Elite Traveler has selected an exclusive VIP experience EXPERT RECOMMENDATIONS 5 We asked top local experts to share their personal recommendations ENJOY ELEGANT SEA-FACING LUXURY AT THE CARLTON for the perfect day in Tel Aviv WHERE TO ➤ STAY 7 ➤ DINE 13 ➤ BE PAMPERED 16 RELAX IN STYLE AT THE BEACH WHAT TO DO ➤ DURING THE DAY 17 ➤ DURING THE NIGHT 19 ➤ FEATURED EVENTS 21 ➤ SHOPPING 22 TASTE SUMPTUOUS GOURMET FLAVORS AT YOEZER WINE BAR NEED TO KNOW ➤ MARINAS 25 ➤ PRIVATE JET TERMINALS 26 ➤ EXCLUSIVE TRANSPORT 27 ➤ USEFUL INFORMATION 28 DISCOVER CUTTING EDGE DESIGNER STYLE AT RONEN ChEN (C) ShAI NEIBURG DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES ELITE DESTINATION GUIDE | TEL AVIV www.elitetraveler.com 2 HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV Don’t miss out on the wealth of attractions, adventures and experiences on offer in ‘The Miami of the Middle East’ el Aviv is arguably the most unique ‘Habuah’ (‘The Bubble’), for its carefree Central Tel Aviv’s striking early 20th T city in Israel and one that fascinates, and fun-loving atmosphere, in which century Bauhaus architecture, dubbed bewilders and mesmerizes visitors. the difficult politics of the region rarely ‘the White City’, is not instantly Built a mere century ago on inhospitable intrudes and art, fashion, nightlife and attractive, but has made the city a World sand dunes, the city has risen to become beach fun prevail. This relaxed, open vibe Heritage Site, and its golden beaches, a thriving economic hub, and a center has seen Tel Aviv named ‘the gay capital lapped by the clear azure Mediterranean, of scientific, technological and artistic of the Middle East’ by Out Magazine, are beautiful places for beautiful people. -

Spousal Abuse Among Immigrants from Ethiopia in Israel

LEA KACEN Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Spousal Abuse Among Immigrants From Ethiopia in Israel This ethnographic study obtains first-hand infor- ‘‘domestic violence’’ in his native Amharic. My mation on spousal abuse from Ethiopian immi- informer replied that there is no such term in their grants in Israel. Data include 23 interviews with language. ‘‘Then how do you describe situations male and female immigrants of various ages and in which a husband beats or insult his wife’’? I 10 professionals who worked with this commu- asked. He answered, ‘‘There is no reason to speak nity as well as observations and documents. The about it.’’ The conversation aroused my curiosity, findings, verified by participants, show that dur- as language is a means used by cultural groups to ing cultural transition, the immigrants’ code of transmit knowledge and shape social norms honor, traditional conflict-solving institutions, (Green, 1995). I asked myself whether there and family role distribution disintegrate. This was no need for the concept because violence situation, exacerbated by economic distress, toward women was nonexistent in Ethiopia, or proved conducive to women’s abuse. Lack of perhaps because there is another term with a sim- cultural sensitivity displayed by social services ilar meaning, or was it that the phenomenon is an actually encouraged women to behave abusively accepted, self-evident norm that need not be dis- toward their husbands and destroy their fami- cussed judgmentally as it is in Western cultures. lies. Discussion focuses on communication fail- Something else troubled me as well. If there is ures in spousal-abuse discourse between no term for domestic violence in Amharic, how immigrants from Ethiopia and absorbing soci- do immigrants from Ethiopia understand this ety, originating in differences in values, behav- concept as used in Israeli society to describe neg- ior, social representations, and insensitive ative situations of violence between husbands culture theories. -

The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann (Pdf)

6/28/2020 The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann » Mosaic THE TRUTH OF THE CAPTURE OF ADOLF EICHMANN https://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/history-ideas/2020/06/the-truth-of-the-capture-of-adolf-eichmann/ Sixty years ago, the infamous Nazi official was abducted in Argentina and brought to Israel. What really happened, what did Hollywood make up, and why? June 1, 2020 | Martin Kramer About the author: Martin Kramer teaches Middle Eastern history and served as founding president at Shalem College in Jerusalem, and is the Koret distinguished fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Listen to this essay: Adolf Eichmann’s Argentinian ID, under the alias Ricardo Klement, found on him the night of his abduction. Yad Vashem. THE MOSAIC MONTHLY ESSAY • EPISODE 2 June: The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann 1x 00:00|60:58 Sixty years ago last month, on the evening of May 23, 1960, the Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion made a brief but dramatic announcement to a hastily-summoned session of the Knesset in Jerusalem: A short time ago, Israeli security services found one of the greatest of the Nazi war criminals, Adolf Eichmann, who was responsible, together with the Nazi leaders, for what they called “the final solution” of the Jewish question, that is, the extermination of six million of the Jews of Europe. Eichmann is already under arrest in Israel and will shortly be placed on trial in Israel under the terms of the law for the trial of Nazis and their collaborators. In the cabinet meeting immediately preceding this announcement, Ben-Gurion’s ministers had expressed their astonishment and curiosity. -

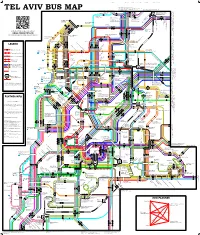

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq.