CONTENTS E V Theme: Revival a N G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Is a Complete Transcript of the Oral History Interview with Mary Goforth Moynan (CN 189, T3) for the Billy Graham Center Archives

This is a complete transcript of the oral history interview with Mary Goforth Moynan (CN 189, T3) for the Billy Graham Center Archives. No spoken words which were recorded are omitted. In a very few cases, the transcribers could not understand what was said, in which case [unclear] was inserted. Also, grunts and verbal hesitations such as “ah” or “um” are usually omitted. Readers of this transcript should remember that this is a transcript of spoken English, which follows a different rhythm and even rule than written English. Three dots indicate an interruption or break in the train of thought within the sentence of the speaker. Four dots indicate what the transcriber believes to be the end of an incomplete sentence. ( ) Word in parentheses are asides made by the speaker. [ ] Words in brackets are comments made by the transcriber. This transcript was created by Kate Baisley, Janyce H. Nasgowitz, and Paul Ericksen and was completed in April 2000. Please note: This oral history interview expresses the personal memories and opinions of the interviewee and does not necessarily represent the views or policies of the Billy Graham Center Archives or Wheaton College. © 2017. The Billy Graham Center Archives. All rights reserved. This transcript may be reused with the following publication credit: Used by permission of the Billy Graham Center Archives, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL. BGC Archives CN 189, T3 Transcript - Page 2 Collection 189, T3. Oral history interview with Mary Goforth Moynan by Robert Van Gorder (and for a later portion of the recording by an unidentified woman, perhaps Van Gorder=s wife), recorded between March and June 1980. -

The Highlands Grapevine

During the month of May we were asked to pray for the nations of Asia and the theme of our prayers was that “God would send out workers to gather in His harvest”. I found this lovely poem written by a man who had a dream. It is based on the story in Matt. 21:18-20 when Jesus looked for fruit on the fig tree and found nothing but leaves. The time of the harvest was ended, And the summer of life was gone, When in from the fields came the reapers, Called home by the dip of the sun; I saw them each bearing a burden Of toilsomely ingathered sheaves; They brought them in love to the Master, But I could bring nothing but leaves. The years that He gave I had wasted, Nor thought I how soon they would fly, While others toiled for the harvest, I carelessly let them slip by; I idled about without purpose, Nor cared I, but now how it grieves; While others brought fruit to their Master, I found I had nothing but leaves. Then soon from my dream I was wakened, And sad was my heart, for I knew That though my life’s day was not over, Ere long I should bid it adieu. I started in shame and in sorrow, I turned from the sin that deceives; Henceforth I must toil for the Saviour Or maybe bring nothing but leaves. (by Jack Selfridge) On the Sunday after Easter, Pete told us all about ‘Doubting Thomas’. I found myself wondering what happened to Thomas. -

Alappuzha Alleppey the Heart of Backwaters

Alappuzha Alleppey The Heart of Backwaters STD Code +91 477 Major Railway Stations Alappuzha Cherthala Chengannur Mavilikkara Kayamkulam Closest Airport Cochin International Airport 7 The wind slowly wafts through the rolling paddy fields, swaying palm fronds to the vast, sedate backwaters. Life has a slow pace in the almost magical village life of Alappuzha. The greenery that stretches as far as eyes can reach, the winding canals, enthralling backwaters, pristine nature makes Alappuzha a dream come true for the casual and serious traveller. The name Alappuzha is derived from Aal Even from the early periods of celebrated historic importance of Alappuzha District. (Sea)+ puzhai (River-mouth). The district ‘Sangam’ age, Kuttanad, known as the Christianity had a foothold in this of Alappuzha (Aleppey) was formed in the rice bowl of Kerala, with its paddy fields, district, even from the 1st century AD. The 17th August, 1957, carving regions out of small streams and canals with lush green church located at Kokkamangalam was the erstwhile Quilon (Kollam) and Kotta- coconut palms, was well known. The one of the seven churches founded by St. yam districts, spreading in 1414sq.km. The name Kuttanad is ascribed to the early Thomas, one of the twelve disciples of district headquarters is at Alappuzha. Cheras who were called the Kuttavans. Jesus Christ. It is generally believed that Alappuzha, the backwater heartland dis- Literary works like “Unnuneeli Sandesam”, he landed at Maliankara in Muziris Port, trict of Kerala, exudes all the bewitching one of the oldest literary works of Kerala, later came to be known as Cranganore charm that Kerala has. -

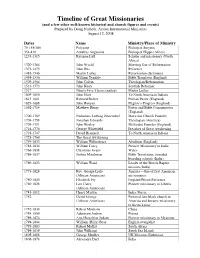

Timeline of Great Missionaries

Timeline of Great Missionaries (and a few other well-known historical and church figures and events) Prepared by Doug Nichols, Action International Ministries August 12, 2008 Dates Name Ministry/Place of Ministry 70-155/160 Polycarp Bishop of Smyrna 354-430 Aurelius Augustine Bishop of Hippo (Africa) 1235-1315 Raymon Lull Scholar and missionary (North Africa) 1320-1384 John Wyclif Morning Star of Reformation 1373-1475 John Hus Reformer 1483-1546 Martin Luther Reformation (Germany) 1494-1536 William Tyndale Bible Translator (England) 1509-1564 John Calvin Theologian/Reformation 1513-1573 John Knox Scottish Reformer 1517 Ninety-Five Theses (nailed) Martin Luther 1605-1690 John Eliot To North American Indians 1615-1691 Richard Baxter Puritan Pastor (England) 1628-1688 John Bunyan Pilgrim’s Progress (England) 1662-1714 Matthew Henry Pastor and Bible Commentator (England) 1700-1769 Nicholaus Ludwig Zinzendorf Moravian Church Founder 1703-1758 Jonathan Edwards Theologian (America) 1703-1791 John Wesley Methodist Founder (England) 1714-1770 George Whitefield Preacher of Great Awakening 1718-1747 David Brainerd To North American Indians 1725-1760 The Great Awakening 1759-1833 William Wilberforce Abolition (England) 1761-1834 William Carey Pioneer Missionary to India 1766-1838 Christmas Evans Wales 1768-1837 Joshua Marshman Bible Translation, founded boarding schools (India) 1769-1823 William Ward Leader of the British Baptist mission (India) 1773-1828 Rev. George Liele Jamaica – One of first American (African American) missionaries 1780-1845 -

The Bible in the Life and Work of Prominent Missionaries of the Far

This material has been provided by Asbury Theological Seminary in good faith of following ethical procedures in its production and end use. The Copyright law of the united States (title 17, United States code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyright material. Under certain condition specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to finish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specific conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. By using this material, you are consenting to abide by this copyright policy. Any duplication, reproduction, or modification of this material without express written consent from Asbury Theological Seminary and/or the original publisher is prohibited. Contact B.L. Fisher Library Asbury Theological Seminary 204 N. Lexington Ave. Wilmore, KY 40390 B.L. Fisher Library’s Digital Content place.asburyseminary.edu Asbury Theological Seminary 205 North Lexington Avenue 800.2ASBURY Wilmore, Kentucky 40390 asburyseminary.edu THE BIBLE IN Tm LIFE AND WORK OP PROMINENT MISSIONARIES OP THR PAR EAST A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Asbury Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Divinity by Jerry V. Cols ten December 1955 A THESIS Submitted to Dr. -

Electronic Kits for Aided Schools

No of school_ finance_ revenue_ no_of_divisi no_of_stude school_name code Type_Name District_name ons_9 nts_9 Electronic Kits 34001 S F A HSS Arthunkal Aided Alappuzha 7 317 3 34003 St Augustine HS Mararikulam Aided Alappuzha 2 81 1 34004 St Augustine HSS Aroor Aided Alappuzha 7 263 3 34008 HF HSS Kattoor Aided Alappuzha 4 167 2 34009 HSS Kandamangalam Aided Alappuzha 5 190 3 34010 St George HS Thankey Aided Alappuzha 3 111 2 34011 VHSS Kanichukulangara Aided Alappuzha 5 189 3 34012 Girl`s HS Kanichukulangara Aided Alappuzha 3 102 2 34015 St Mathew`s HS Kannankara Aided Alappuzha 2 90 1 34016 ABVHSS Muhamma Aided Alappuzha 5 208 3 34017 ECEK Union HS Kuthiathode Aided Alappuzha 3 108 2 34020 NSS HSS Panavally Aided Alappuzha 4 174 2 34021 VJHSS Naduvath Nagar Aided Alappuzha 10 416 4 34025 St Mary`s Girl`s HS Cherthala Aided Alappuzha 6 344 3 34026 SMSJ HS Thycattuserry Aided Alappuzha 1 29 1 34027 PSHS Pallippuram Aided Alappuzha 1 29 1 34028 TD HSS Thuravoor Aided Alappuzha 9 369 4 34029 St Sebastian HS Pallithode Aided Alappuzha 3 149 2 34030 St Michel`s HS Kavil Aided Alappuzha 4 138 2 34034 SNHSS Sreekandeswram Aided Alappuzha 8 336 4 34035 St Theresas HS Manappuram Aided Alappuzha 3 143 2 34037 St.Raphael's H S Ezhupunna Aided Alappuzha 6 231 3 34038 Holy Family HSS Muttom Aided Alappuzha 5 270 3 34041 SCS HS Valamangalam Aided Alappuzha 2 91 1 34042 ST Antony`s HS Kokkamangalam Aided Alappuzha 2 85 1 34046 MTHS Muhamma Aided Alappuzha 5 211 3 No of school_ finance_ revenue_ no_of_divisi no_of_stude school_name code Type_Name District_name ons_9 nts_9 Electronic Kits 34047 SN Trust HSS SN Puram Aided Alappuzha 4 157 2 35001 S D V B H S S Alappuzha Aided Alappuzha 4 145 2 35002 St. -

A Brief Survey of Missions

2 A Brief Survey of Missions A BRIEF SURVEY OF MISSIONS Examining the Founding, Extension, and Continuing Work of Telling the Good News, Nurturing Converts, and Planting Churches Rev. Morris McDonald, D.D. Field Representative of the Presbyterian Missionary Union an agency of the Bible Presbyterian Church, USA P O Box 160070 Nashville, TN, 37216 Email: [email protected] Ph: 615-228-4465 Far Eastern Bible College Press Singapore, 1999 3 A Brief Survey of Missions © 1999 by Morris McDonald Photos and certain quotations from 18th and 19th century missionaries taken from JERUSALEM TO IRIAN JAYA by Ruth Tucker, copyright 1983, the Zondervan Corporation. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House, Grand Rapids, MI Published by Far Eastern Bible College Press 9A Gilstead Road, Singapore 309063 Republic of Singapore ISBN: 981-04-1458-7 Cover Design by Charles Seet. 4 A Brief Survey of Missions Preface This brief yet comprehensive survey of Missions, from the day sin came into the world to its whirling now head on into the Third Millennium is a text book prepared specially by Dr Morris McDonald for Far Eastern Bible College. It is used for instruction of her students at the annual Vacation Bible College, 1999. Dr Morris McDonald, being the Director of the Presbyterian Missionary Union of the Bible Presbyterian Church, USA, is well qualified to write this book. It serves also as a ready handbook to pastors, teachers and missionaries, and all who have an interest in missions. May the reading of this book by the general Christian public stir up both old and young, man and woman, to play some part in hastening the preaching of the Gospel to the ends of the earth before the return of our Saviour (Matthew 24:14) Even so, come Lord Jesus Timothy Tow O Zion, Haste O Zion, haste, thy mission high fulfilling, to tell to all the world that God is Light; that He who made all nations is not willing one soul should perish, lost in shades of night. -

The New Missionary Force Mission from the Majority World

Vol. 11 No. 3 September–December 2016 The New Missionary Force Mission from the Majority World MCI(P)181/03/20161 Contents Mission Round Table Vol. 11 No. 3 September–December 2016 03 Editorial – Walter McConnell 04 Partnering with the Majority World in the Global Paradigm – Eldon Porter 10 The Challenge and Opportunity of Urban Ministry in China – H. P. 21 Indigenous Mission Movements in China – Steve Z. 33 Partnership with the Global Church: Implications for the Global East – An Interview with Patrick Fung 36 With Bethel in Manchuria – Leslie T. Lyall Cover Photo: The cover photos illustrate just how international mission has become. The first photo shows OMF members at the Central Thailand Field Conference in 1958. Contrast this with the second photo taken at a recent OMF Field Conference held in Thailand and it becomes clear how global OMF has become. Five continents and more than seventeen countries were represented. Nations included Australia, Brazil, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, South Africa, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, The Netherlands, The Philippines, Uruguay, UK, and USA. Also noticeable is an increasing number of ethnic Asians joining from non-Asian countries. Archive photo source: The Millions (March 1958): 27. Photo Credits: Donations: Download: WEA p. 3, Walter McConnell If you would like to contribute to the work PDF versions of Mission Round Table can be of Mission Round Table, donations can be downloaded from www.omf.org/mrt. made to OMF International and earmarked for “Mission Round Table project.” The editorial content of Mission Round Table reflects the opinions of the various authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the views of OMF International (IHQ) Ltd. -

Kerala History Timeline

Kerala History Timeline AD 1805 Death of Pazhassi Raja 52 St. Thomas Mission to Kerala 1809 Kundara Proclamation of Velu Thampi 68 Jews migrated to Kerala. 1809 Velu Thampi commits suicide. 630 Huang Tsang in Kerala. 1812 Kurichiya revolt against the British. 788 Birth of Sankaracharya. 1831 First census taken in Travancore 820 Death of Sankaracharya. 1834 English education started by 825 Beginning of Malayalam Era. Swatithirunal in Travancore. 851 Sulaiman in Kerala. 1847 Rajyasamacharam the first newspaper 1292 Italiyan Traveller Marcopolo reached in Malayalam, published. Kerala. 1855 Birth of Sree Narayana Guru. 1295 Kozhikode city was established 1865 Pandarappatta Proclamation 1342-1347 African traveller Ibanbatuta reached 1891 The first Legislative Assembly in Kerala. Travancore formed. Malayali Memorial 1440 Nicholo Conti in Kerala. 1895-96 Ezhava Memorial 1498 Vascoda Gama reaches Calicut. 1904 Sreemulam Praja Sabha was established. 1504 War of Cranganore (Kodungallor) be- 1920 Gandhiji's first visit to Kerala. tween Cochin and Kozhikode. 1920-21 Malabar Rebellion. 1505 First Portuguese Viceroy De Almeda 1921 First All Kerala Congress Political reached Kochi. Meeting was held at Ottapalam, under 1510 War between the Portuguese and the the leadership of T. Prakasam. Zamorin at Kozhikode. 1924 Vaikom Satyagraha 1573 Printing Press started functioning in 1928 Death of Sree Narayana Guru. Kochi and Vypinkotta. 1930 Salt Satyagraha 1599 Udayamperoor Sunahadhos. 1931 Guruvayur Satyagraha 1616 Captain Keeling reached Kerala. 1932 Nivarthana Agitation 1663 Capture of Kochi by the Dutch. 1934 Split in the congress. Rise of the Leftists 1694 Thalassery Factory established. and Rightists. 1695 Anjengo (Anchu Thengu) Factory 1935 Sri P. Krishna Pillai and Sri. -

"By My Spirit"

"BY MY SPIRIT" BY THE REV. JONATHAN GOFORTH, D.D. MARSHALL, MORGAN & SCOTT, LTD. l..oNDON AND EDINBURGH Printed in Great Britain by Hunt, Barnard & Co., Ltd~, London and Aylesbury, PREFACE A MISSIONARY of the Canadian Presbyterian Church, Dr. Jonathan Goforth, has, for a long period of years, been stationed in Manchuria, China, and during his ministry there has been wonderfully used of God, not only in declaring the incomparable message of a Saviour's redeeming love, but also in the inauguration of Revival movements which have brought rich and abiding blessing upon the Church and its members. For a number of years p1essure has been brought to bear upon him to write an account of his Revival experiences in the hope that these might have a message for the whole Church of Christ and point the way to that spiritual quicken ing of which it is so much in need . But while realising the importance of making known to all the world the great things which the Lord has done for His people· in China, Dr. Goforth has felt that the preaching of the Gospel had first claim upon his time, and to that urgent task he devoted himself with a zeal and an energy that left no opportunity for other pursuits. Recently, 1'owever, a change of circumstances gave to him the opening for which he had been waiting. Laid aside from preaching for several months, and having his youngest son, Frederick, with him on a visit, he PREFACE dictated to him the substance of this volume, and thus at last the thrilling record of the mighty move ments of the Holy Spirit has been prepared for press. -

A Study on Personal Finance of the Coir-Workers at Cherthala- with Special Reference to Their Savings and Investments

A STUDY ON PERSONAL FINANCE OF THE COIR-WORKERS AT CHERTHALA- WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THEIR SAVINGS AND INVESTMENTS Report of the Minor Research Project Submitted to the UGC- SWRO- Bangalore By Dr. Jacob Thomas Associate Professor and Head Department of Commerce CMS College Kottayam Kerala- 686001 October 2015 DECLARATION I Dr. Jacob Thomas, Associate Professor and Head, Department of Commerce, CMS College Kottayam, Kerala, 686001, hereby declare that the research report titled ‘A Study on Personal Finance of the Coir-workers at Cherthala- with Special Reference to their Savings and Investmenst, is the record of my bonafide work done under the Minor Project Scheme of the UGC. I also declare that any report with the similar title has not been submitted by myself for the award of any degree, diploma or similar title or report for complying with the requirements of any Project sponsored by the UGC or other similar statutory organizations. Signature Kottayam 30-10-2015 Dr. Jacob Thomas Chapter I Introduction and Design of the Study The traditional industrial sector comprising bell metal craft, cashew-processing, coir manufacturing and handloom weaving, is generally perceived as ‘the access around which the rural economy of Kerala gets rotated’, obviously, the policy-makers during the post independent period, with a slew of perfectly matching strategic measures, had attempted to ascend the sector as an ‘employment-reservoir’, targeting the individuals and households who domiciled in villages or hamlets of Kerala. Overwhelmingly, the key factor for the sustainable growth of the traditional industry is the skill and the craftsmanship of the workers who have been associated with this source of bread-winning since their childhood itself. -

District Wise IT@School Master District School Code School Name Thiruvananthapuram 42006 Govt

District wise IT@School Master District School Code School Name Thiruvananthapuram 42006 Govt. Model HSS For Boys Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42007 Govt V H S S Alamcode Thiruvananthapuram 42008 Govt H S S For Girls Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42010 Navabharath E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42011 Govt. H S S Elampa Thiruvananthapuram 42012 Sr.Elizabeth Joel C S I E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42013 S C V B H S Chirayinkeezhu Thiruvananthapuram 42014 S S V G H S S Chirayinkeezhu Thiruvananthapuram 42015 P N M G H S S Koonthalloor Thiruvananthapuram 42021 Govt H S Avanavancheri Thiruvananthapuram 42023 Govt H S S Kavalayoor Thiruvananthapuram 42035 Govt V H S S Njekkad Thiruvananthapuram 42051 Govt H S S Venjaramood Thiruvananthapuram 42070 Janatha H S S Thempammood Thiruvananthapuram 42072 Govt. H S S Azhoor Thiruvananthapuram 42077 S S M E M H S Mudapuram Thiruvananthapuram 42078 Vidhyadhiraja E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42301 L M S L P S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42302 Govt. L P S Keezhattingal Thiruvananthapuram 42303 Govt. L P S Andoor Thiruvananthapuram 42304 Govt. L P S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42305 Govt. L P S Melattingal Thiruvananthapuram 42306 Govt. L P S Melkadakkavur Thiruvananthapuram 42307 Govt.L P S Elampa Thiruvananthapuram 42308 Govt. L P S Alamcode Thiruvananthapuram 42309 Govt. L P S Madathuvathukkal Thiruvananthapuram 42310 P T M L P S Kumpalathumpara Thiruvananthapuram 42311 Govt. L P S Njekkad Thiruvananthapuram 42312 Govt. L P S Mullaramcode Thiruvananthapuram 42313 Govt. L P S Ottoor Thiruvananthapuram 42314 R M L P S Mananakku Thiruvananthapuram 42315 A M L P S Perumkulam Thiruvananthapuram 42316 Govt.