1 Introduction 2 a Proposed Theory and Method for the Incorporation of Comic Books As Primary Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Did They Go

BRITISH ‘BABY BOOMER’ NOSTALGIA Compiled by David Challinor Saluting AA Men Cream on Milk The Children’s Newspaper Shaving in Barbers Time Guns Foot X-Ray Machines in Shoe Shops Pea Shooters Pushers-up Same Day Post Passing Bells Subscription Libraries Boxing Kangaroos Dunces Caps Home-made Fireworks Aluminium Nameplate Machines at Stations German Bands Breton Onion Sellers Romany Caravans Ceiling Clocks Paint Boxes Electric Shock Therapy Bona Fide Travellers Bird – Nesting Apache Dancing Audiphones Aunt Sallies John Bull Puncture Repair Outfits & Printing sets Office Boys White Sugar Mice Camp Coffee Crystal Radio Sets Gas Mantles Guineas Boys Shouting the News Life Preservers Liquorice Imps/ Sherbet Pipes and Dabs Lobby Lud Cigarette Cards Driving Cattle through Towns Tripe Shops Continuous Performance School Ink, Inkwells and Ink Monitors Paper Chases Skipping Seasonal Children’s Games (conkers, marbles) Muffin Men Gob-stoppers Rag and Bone Men (goldfishes for junk) Beetle Drives Card Indexes in Libraries Change Receptacles on Overhead Wire Pulleys Reins on Toddlers Silver Cigarette Cases ‘Fly-proof’ Metal Grilles on Meat-safes Sticky Fly Paper DDT Memory Men (Leslie Welch) Kewpie Dolls Cigarette Holders Bells to Call the Chambermaid in hotel rooms Children’s Gardens Music Halls Pierrots/Black and White Minstrels School Milk Empire Day Pork Butchers Polite Children Blackberrying Laxative Chocolate Tuck Shops Ticking Clocks Flying Boats Rubber Bathing Caps Train Spotting Buying Pickles by the Basin Motor Cycle Sidecars Milk Churns Errand -

Fudge the Elf

1 Fudge The Elf Ken Reid The Laura Maguire collection Published October 2019 All Rights Reserved Sometime in the late nineteen nineties, my daughter Laura, started collecting Fudge books, the creation of the highly individual Ken Reid. The books, the daily strip in 'The Manchester Evening News, had been a part of my childhood. Laura and her brother Adam avidly read the few dog eared volumes I had managed to retain over the years. In 2004 I created a 'Fudge The Elf' website. This brought in many contacts, collectors, individuals trying to find copies of the books, Ken's Son, the illustrator and colourist John Ridgeway, et al. For various reasons I have decided to take the existing website off-line. The PDF faithfully reflects the entire contents of the original website. Should you wish to get in touch with me: [email protected] Best Regards, Peter Maguire, Brussels 2019 2 CONTENTS 4. Ken Reid (1919–1987) 5. Why This Website - Introduction 2004 6. Adventures of Fudge 8. Frolics With Fudge 10. Fudge's Trip To The Moon 12. Fudge And The Dragon 14. Fudge In Bubbleville 16. Fudge In Toffee Town 18. Fudge Turns Detective Savoy Books Editions 20. Fudge And The Dragon 22. Fudge In Bubbleville The Brockhampton Press Ltd 24. The Adventures Of Dilly Duckling Collectors 25. Arthur Gilbert 35. Peter Hansen 36. Anne Wilikinson 37. Les Speakman Colourist And Illustrator 38. John Ridgeway Appendix 39. Ken Reid-The Comic Genius 3 Ken Reid (1919–1987) Ken Reid enjoyed a career as a children's illustrator for more than forty years. -

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 Less Doctor Who Except for 1975

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 less Doctor Who except for 1975 Annual aa TITLE, EXCLUDING “THE”, c=circa where no © displayed, some dates internal only Annual 2000AD Annual 1978 b3 Annual 2000AD Annual 1984 b3 Annual-type Abba Gift Book © 1977 LR4 Annual ABC Children’s Hour Annual no.1 dj LR7w Annual Action Annual 1979 b3 Annual Action Annual 1981 b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 LR5 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 2, (1 for repair of other) b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Sir Lancelot circa 1958, probably no.1 b3 Annual TVT A-Team Annual 1986 LR4 Annual Australasian Boy’s Annual 1914 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual 1912 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual c/1930 plane over ship dj not matching? LR Annual Australian Girl’s Annual 16? Hockey stick cvr LR Annual-type Australian Wonder Book ©1935 b3 Annual TVT B.J. and the Bear © 1981 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1985 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1986 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1981 LR5 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1964 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1971 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1981 b3 Annual Beano Book 1983 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1985 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1987 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1976 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1977 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1982 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1987 LR4 Annual TVT Ben Casey Annual © 1963 yellow Sp LR4 Annual Beryl the Peril 1977 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual Beryl the Peril 1988 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual TVT Beverly Hills 90210 Official Annual 1993 LR4 Annual TVT Bionic -

'Taste of the Towns' Fundraiser Benefits Marching Band

Sam’son says “Call my Dad” Mortgage rates have fallen, don’t wait! Have high PMI payments? Maybe an FHA loan? Call Ron for help 508-892-8988! Face-To-Face Mortgage Co. MA Mortgage Ronald F. A local man (DPHS 1982) and company owner since 2000 broker number LaPrade Call 508-892-8988 • Email [email protected] NMLS #1241 DP INVADERS No Cost to tryout! BASEBALL/SOFTBALL TRAVEL TEAMS Tryouts being held at DOUBLE PLAY SPORTS! TRYOUTS SUNDAY NOVEMBER 9 • 11-1 Softball ASA Baseball AAU 10U -16U U10-U13 If you have any questions please feel free to email address below. 190 MAIN STREET • CHERRY VALLEY MA 01611 • 508-892-8900 www.doubleplaysportsfitness.com • email: [email protected] Mailed free to requesting homes in East Brookfield, West Brookfield, North Brookfield, Brookfield, Leicester and Spencer Vol. XXXV, No. 43 PROUD MEDIA SPONSOR OF RELAY FOR LIFE OF THE GREATER SOUTHBRIDGE AREA! COMPLIMENTARY HOME DELIVERY ONLINE: WWW.SPENCERNEWLEADER.COM Friday, October 31, 2014 THIS WEEK’S QUOTE ‘Taste of the Towns’ fundraiser “Real success is finding your lifework in the benefits marching band work that you love.” David COMMUNITY EVENT CONTINUES TRADITION OF SUPPORT McCullough BY KEVIN FLANDERS in fundraising, offering a variety NEWS STAFF WRITER of delicious foods. All proceeds SPENCER — Guests got a support the DPHS Marching INSIDE true “Taste of the Towns” last Panther Band, which recently Saturday, Oct. 25, at David took home three stars from an Obituaries ...........B Sect Prouty High School, as the annu- impressive showing at a state al event drew a strong lineup of competition. -

THE STOR Y Rarjer

THE STORy rArJER JAl\.LARY 1954 COLLECTOR No. 51 :: Vol. 3 6th Chri,tma' J,,ue, The Magner, i'o. 305, December 13, 191 "l From the Editor's NOTEBOOK HAVE Volume I, the first 26 name pictured in The Srory Paper issues, of the early Harms Collet!or No. 48, but the same I worth weekly paper for publisher, Rrett), a "large num· women, Forger-Me-Nor, which ber" of S11rpris�s, Plucks, Union was founded, I judge - for the Jacks, Marwls, and True Blues cover-pages are missing-late in were offereJ at one shilling for 1891. In No. 12, issued probably 48, post free to any address. Un in January 1892, there is mention like Forgec-Me-Nors in 1892, these of a letter from a member of papers must have been consi The Forget-Me-Not Club. ln the dered of little value in 1901. words of the Editress (as she What a difference today! calls herself): IF The Amalgamated Press A member of the Clul> tt•rites IO had issued our favorite papers inform me rha1 she inserted an ad in volumes, after the manner of vertisement in E x change and Mart, Chums in its earlier years, there offering Rider Haggard's "Jess" and would doubtless he a more Longfellow's poems for a copy of plentiful supply of Magnets and No. 1 of Forget-Me-Not, l>ut she Gems and the rest today. They did not receive an offer. This speaks did not even make any great 1'0lumes for 1he value of the earl: prndicc of providing covers for numbers of Forger-Me-Not. -

Layout 1 (Page 1)

Mailed free to requesting homes in East Brookfield, West Brookfield, North Brookfield, Brookfield, Leicester and Spencer Vol. 32, No. 41 COMPLIMENTARY HOME DELIVERY, 75 CENTS ON NEWSSTANDS ONLINE: WWW.SPENCERNEWLEADER.COM ‘Experience is the name so many people give to their mistakes.’ Friday, October 10, 2008 ‘From a Tiger to a Cougar’ THROWING A HELPING HAND KUSTIGIAN READIES FOR NEW POST BY DAVID DORE NEW LEADER STAFF WRITER From where he sat last week at Douglas High School, Brett Kustigian was a little over an hour away from the towns of Warren and West Brookfield. In his mind, though, he was on the shores of Lake Wickaboag, remem- bering the summers his family spent there — and looking forward to the fish he might catch with his young sons. Kustigian’s twin loves of “playing with my kids and fishing” were appar- ent the moment someone walks into the principal’s office. Behind his desk, along with some of the degrees he has David Dore photo earned in his 34 years, were numer- ous photographs of him and his two New Quaboag Regional School District Superintendent Brett Kustigian sits in his office at Douglas High School last week. Turn To KUSTIGIAN, page 17 Spencer Town Meeting Thursday Alana Melanson photo SPENDING, BYLAW CHANGES ON WARRANT WEST BROOKFIELD — Rebecca Webber instructs tour Tyler Boutiette, 21, of BY DAVID DORE will still face a vote. der truck for the Fire Department Millbury, on how to “raise the walls” of the clay piece he is throwing for the NEW LEADER STAFF WRITER The 22-article session will begin at 7 (pending a vote at the Nov. -

Take a Running Jump! Your Sport Gags Inside

! ISSUE 379 – NOVEMBER 2005! AUTUMN 2005 The Jester ABRIDGED TAKE A RUNNING JUMP! YOUR SPORT GAGS INSIDE TECHNOPHILES BYTE BACK / THE CARTOONIST BOUNCERS “Whaddya mean it looks nothing like you?” PAUL BAKER PROFILES HIS FAVOURITE CARICATURISTS THE MARVEL OF BLAZERMAN / BILL RITCHIE ON FILM FUN STEVE WAY Q&A / CHAIRMAN ON, ER, SHEDS AND ONIONS The Newsletter of the Cartoonists’ Club of Great Britain THE JESTER ISSUE 379 – NOVEMBER 2005 CCGB ONLINE: WWW.CCGB.ORG.UK The Jester News Issue 379 - November 2005 Excellence in 2003. He recently Published 11 times a year became the official artist for the arts by The Cartoonists’ Club materials maker Edding UK. of Great Britain St. Just The CCGB Committee the ticket Chairman: Terry Christien 020–8892 3621 From Roger Penwill: Just back [email protected] from another excellent weekend at the Secretary: Richard Tomes St. Just festival. Once again the 0121–706 7652 exhibitions were extensive and [email protected] excellent. Among them was a superb BOSC exhibition and one of the Treasurer: Jill Kearney innovative semi-3D work of Mougey. 020–8590 8942 The food was better than before and wine was good and plentiful. Sue Les Barton: 01895–236 732 Burleigh had made it there at the end [email protected] of Toontrek and by the time we Clive Collins: 01702–557 205 By George, he’s arrived, she was fully immersed in the whole St. Just experience. [email protected] on the telly St. Just is now the biggest and best in Neil Dishington: 020–8505 0134 the world, having grown from a very [email protected] CLUB member George Williams small start (there were just five Ian Ellery: 01424–718 209 was featured on The Paul O’Grady cartoonists at the 2nd festival). -

THE FUNNIES of AUGUST: AMERICAN EDITORIAL CARTOONS in the OPENING MONTHS of the SPANISH CIVIL WAR by Wesley Moore HONORS THESIS

THE FUNNIES OF AUGUST: AMERICAN EDITORIAL CARTOONS IN THE OPENING MONTHS OF THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR by Wesley Moore HONORS THESIS Submitted to Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors College May 2020 Thesis Supervisor: Louie Dean Valencia-García Second Reader: Joshua Paddison ABSTRACT This thesis studies American editorial cartoons depicting the Spanish Civil War of 1936. The other goal of this thesis is to create an exhibit display case in the Taylor-Murphy building showing select comics from the research for casual audiences. I chose comics specifically because the opinions of newspaper political cartoons appeal or market to a wide portion of the public, making them a compelling source to study the popular opinion and media of the time. The comics came from the pages of the New York Times, Chicago Daily Tribune, and Washington Post and from the months of July, August, and September 1936. The newspapers were chosen for their status as major publications, their name recognition to modern exhibit viewers, and to limit the scope of the project. Cartoons were researched from these publications in the time frame of July 17th, the beginning of the military coup, to September 30th. The end of the date range was chosen to limit the scope of the project and to focus on this specific historical moment at the onset of the war. Few studies have been completed on the American cartoons that portrayed the Spanish Civil War, so this project is helping to fill that void. Some of the trends noticeable in these months were a set of common visual clichés, simplification of the conflict, rejection of both sides of the Civil War, and an association of the political left in Spain with Roosevelt and the New Deal. -

Colle1ctors' Digest

S PRY PAPER COLLE 1CTORS' DIGEST VOL. 46 No. 551 NOVEMBER 1992 BETTY AGAINST THE SNOBSI 8M u TIH Fri ... d atie ,..,,.,,d I'' II\ thi• IHllt.) - • ..a.... - No, 3, Vol . I ,) PU81. I SH£0 £VER Y TUESDAY, [Wnk End•nll f'~b,.,&ry l&th, 191 1, ONCORPORATING NORMAN SHAW) ROBIN OSBORNE, 84 BELVEDERE ROAD, LONDON SE 19 2HZ PHONE (BETWEEN 11 A.M . • 10 P.M.) 081-771 0541 Hi People, Varied selection of goodies on offer this month:- J. Many loose issues of TRIUMPH in basically very good condition (some staple rust) £3. each. 2. Round volume of TRIUMPH Jan-June 1938 £80. 3. GEM . bound volumes· all unifonn · 581. 620 (29/3 · 27.12.19) £110 621 . 646 (Jan· June 1920) £ 80 647 • 672 (July · Dec 1920) £ 80 4. 2 Volumes of MAGNET uniformly bound:- October 1938 - March 1939 £ 60 April 1939 - September 1939 £ 60 (or the pair for £100) 5. SWIFT - Vol. 7, Nos.1-53 & Vol. 5 Nos.l-52, both bound in single volumes £50 each. Many loose issues also available at £1 each - please enquire. 6. ROBIN - Vol.5, Nos. 1-52, bound in one volume £30. Many loose issues available of this title and other pre-school papers like PLA YHOUR, BIMBO, PIPPIN etc. at 50p each (substantial discounts for quantity), please enquire. 7. EAGLE - many issues of this popular paper. including some complete unbound volumes at the following rates: Vol. 1-10, £2 each, and Vol. 11 and subsequent at £1 each. Please advise requirements. 8. 2000 A.D. -

European Journal of American Studies, 8-1 | 2013 What’S the Matter with Benjamin O

European journal of American studies 8-1 | 2013 Spring 2013 What’s the matter with Benjamin O. Flower? Populism, antimonopoly politics and the “paranoid style” at the turn of the century Jean-Louis Marin-Lamellet Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/10086 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.10086 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Jean-Louis Marin-Lamellet, “What’s the matter with Benjamin O. Flower?”, European journal of American studies [Online], 8-1 | 2013, Online since 06 September 2013, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/ejas/10086 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.10086 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License What’s the matter with Benjamin O. Flower? 1 What’s the matter with Benjamin O. Flower? Populism, antimonopoly politics and the “paranoid style” at the turn of the century Jean-Louis Marin-Lamellet 1 As an editor of several magazines and a publisher, Boston reformer Benjamin Orange Flower (1858-1918, figure 1) publicized and advocated many Progressive and radical causes of his times: Populism, woman suffrage, direct legislation, public ownership of utilities, public works for the unemployed, railroad regulation and temperance to name but a few examples.1 In the 1910s, he denounced the “medical monopolies” that wanted to crush alternative medicine. At the end of his life, he also edited a widely-circulated anti-Catholic newspaper, The Menace. Flower exemplified “how men of this era thought in strange theoretical combinations” and opened the pages of his magazines to all the unorthodox ideas of his times, thus acquiring the reputation of a “radical crank.”2 He believed that his editorial policy should illustrate the American spirit of freedom; the intense intellectual activity would then be conducive to reforms.3 European journal of American studies, 8-1 | 2013 What’s the matter with Benjamin O. -

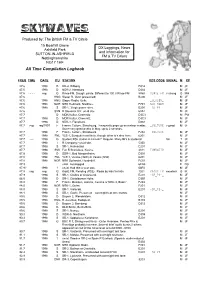

All Time Compilation Logbook by Date/Time

SKYWAVES Produced by: The British FM & TV Circle 15 Boarhill Grove DX Loggings, News Ashfield Park and Information for SUTTON-IN-ASHFIELD FM & TV DXers Nottinghamshire NG17 1HF All Time Compilation Logbook FREQ TIME DATE ITU STATION RDS CODE SIGNAL M RP 87.6 1998 D BR-4, Dillberg. D314 M JF 87.6 1998 D NDR-2, Hamburg. D382 M JF 87.6 - - - - reg G Rinse FM, Slough. pirate. Different to 100.3 Rinse FM 8760 RINSE_FM v strong GMH 87.6 HNG Slager R, Gyor (presumed) B206 M JF 87.6 1998 HNG Slager Radio, Gyšr. _SLAGER_ MJF 87.6 1998 NOR NRK Hedmark, Nordhue. F701 NRK_HEDM MJF 87.6 1998 S SR-1, 3 high power sites. E201 -SR_P1-_ MJF 87.6 SVN R Slovenia 202, un-id site. 63A2 M JF 87.7 D MDR Kultur, Chemnitz D3C3 M PW 87.7 1998 D MDR Kultur, Chemnitz. D3C3 M JF 87.7 1998 D NDR-4, Flensburg. D384 M JF 87.7 reg reg/1997 F France Culture, Strasbourg. Frequently pops up on meteor scatter. _CULTURE v good M JF Some very good peaks in May, up to 2 seconds. 87.7 1998 F France Culture, Strasbourg. F202 _CULTURE MJF 87.7 1998 FNL YLE-1, Eurajoki most likely, though other txÕs also here. 6201 M JF 87.7 ---- 1998 G Student RSL station in Lincoln? Regular. Many ID's & students! fair T JF 87.7 1998 I R Company? un-id site. 5350 M JF 87.7 1998 S SR-1, Halmastad. E201 M JF 87.7 1998 SVK Fun R Bratislava, Kosice. -

An Annual Treat!

Scottish Memories An annual treat! Young people might be more interested in the virtual worlds of their video games these days, and many toys and comics have been long forgotten, but there’s one stocking-filler stalwart that remains a popular present for young and old – the annual oday millions of annuals are has passed, whereas an annual with purchased each Christmas, a non-Xmas themed cover is likely covering subjects as varied to sell into January and February. as Dr Who, Blue Peter Some of the covers extended from the T and the Brownies, with front to the rear cover and are very youngsters thrilled to receive a fun, appealing to the eye – Beano from the hardback book that is intended to be mid 1950s spring to mind.’ enjoyed throughout the coming year. Inside the annuals, readers were, Take a look at most kids’ bookshelves and still are, treated to a mix of longer and you’ll no doubt see the uniform stories, jokes, puzzles, and, perhaps spines of a favourite annual… if only most importantly to today’s annual we older, supposedly wiser folk had kept collectors, wonderful, bright artwork, our Broons, Beano and Buster annuals bringing together the readers’ favourite from all those years ago, we could be sat characters and subjects in one title. on a goldmine. According to collector- Perhaps you remember receiving turned-comic-and-annual-auctioneer Phil copies of the Rupert Bear annual each Shrimpton, many old annuals are now year, with the beautifully drawn strips worth hundreds of pounds. ‘The first giving the reader the choice of enjoying Broons and Oor Wullie annuals from a quick version or a more in-depth story.