Hereby Granted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2012 Florida State Law Magazine

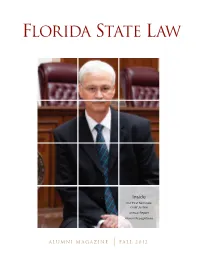

FLORIDA STATE LAW Inside Our First Seminole Chief Justice Annual Report Alumni Recognitions ALUMNI MAGAZINE FALL 2012 Message from the Dean Jobs, Alumni, Students and Admissions Players in the Jobs Market Admissions and Rankings This summer, the Wall Street The national press has highlighted the related phenomena Journal reported that we are the of the tight legal job market and rising student indebtedness. nation’s 25th best law school when it More prospective applicants are asking if a law degree is worth comes to placing our new graduates the cost, and law school applications are down significantly. in jobs that require law degrees. Just Ours have fallen by approximately 30% over the past two years. this month, Law School Transparency Moreover, our “yield” rate has gone down, meaning that fewer ranked us the nation’s 26th best law students are accepting our offers of admission. Our research school in terms of overall placement makes clear: prime competitor schools can offer far more score, and Florida’s best. Our web generous scholarship packages. To attract the top students, page includes more detailed information on our placement we must limit our enrollment and increase scholarship awards. outcomes. In short, we rank very high nationally in terms We are working with our university administration to limit of the number of students successfully placed. Although our our enrollment, which of course has financial implications average starting salary of $58,650 is less than those at the na- both for the law school and for the central university. It is tion’s most elite private law schools, so is our average student also imperative to increase our endowment in a way that will indebtedness, which is $73,113. -

Reform of the Elected Judiciary in Boss Tweed’S New York

File: 3 Lerner - Corrected from Soft Proofs.doc Created on: 10/1/2007 11:25:00 PM Last Printed: 10/7/2007 6:34:00 PM 2007] 109 FROM POPULAR CONTROL TO INDEPENDENCE: REFORM OF THE ELECTED JUDICIARY IN BOSS TWEED’S NEW YORK Renée Lettow Lerner* INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................... 111 I. THE CONSTITUTION OF 1846: POPULAR CONTROL...................... 114 II. “THE THREAT OF HOPELESS BARBARISM”: PROBLEMS WITH THE NEW YORK JUDICIARY AND LEGAL SYSTEM AFTER THE CIVIL WAR .................................................. 116 A. Judicial Elections............................................................ 118 B. Abuse of Injunctive Powers............................................. 122 C. Patronage Problems: Referees and Receivers................ 123 D. Abuse of Criminal Justice ............................................... 126 III. THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1867-68: JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE............................................................. 130 A. Participation of the Bar at the Convention..................... 131 B. Natural Law Theories: The Law as an Apolitical Science ................................... 133 C. Backlash Against the Populist Constitution of 1846....... 134 D. Desire to Lengthen Judicial Tenure................................ 138 E. Ratification of the Judiciary Article................................ 143 IV. THE BAR’S REFORM EFFORTS AFTER THE CONVENTION ............ 144 A. Railroad Scandals and the Times’ Crusade.................... 144 B. Founding -

—FOR PUBLICATION— in the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the EASTERN DISTRICT of PENNSYLVANIA THOMAS SKÖLD, Plaintiff, V

—FOR PUBLICATION— IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA THOMAS SKÖLD, Plaintiff, v. CIVIL ACTION GALDERMA LABORATORIES, L.P.; NO. 14-5280 GALDERMA LABORATORIES, INC.; and GALDERMA S.A., Defendants. OPINION I. INTRODUCTION Before the Court are Defendants Galderma Laboratories, L.P. and Galderma Laboratories, Inc.’s Motion to Dismiss and Motion to Stay Pending the Outcome of the Administrative Proceeding, Plaintiff Thomas Sköld’s Response in Opposition thereto, and Galderma L.P. and Galderma Inc.’s Reply, as well as Defendant Galderma S.A.’s Motion to Dismiss and Motion to Stay Pending the Outcome of the Administrative Proceeding, the Plaintiff’s Response in Opposition thereto, and Galderma S.A.’s Reply.1 The Court held oral argument on all pending motions on March 19, 2015. For the reasons that follow, the motion to stay shall be denied as moot, the motions to dismiss for failure to state a claim shall be granted in part, and the motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction shall be denied. 1 Galderma S.A. was served after Galderma Laboratories, L.P. and Galderma Laboratories, Inc. had filed their motion to dismiss. Galderma S.A. then filed its own motion to dismiss, incorporating the arguments contained in L.P. and Inc.’s motion to dismiss Sköld’s state-law claims and also arguing separately that this Court cannot exercise either general or specific personal jurisdiction over it. See S.A. Mot. to Dismiss at 11. Hereinafter, any reference in this Opinion to an argument made by “the Defendants” collectively will be used in the context of an argument asserted by Galderma Laboratories, L.P. -

Disentangling the Sixth Amendment

ARTICLES * DISENTANGLING THE SIXTH AMENDMENT Sanjay Chhablani** TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.............................................................................488 I. THE PATH TRAVELLED: A HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF THE COURT’S SIXTH AMENDMENT JURISPRUDENCE......................492 II. AT A CROSSROADS: THE RECENT DISENTANGLEMENT OF THE SIXTH AMENDMENT .......................................................505 A. The “All Criminal Prosecutions” Predicate....................505 B. Right of Confrontation ...................................................512 III. THE ROAD AHEAD: ENTANGLEMENTS YET TO BE UNDONE.................................................................................516 A. The “All Criminal Prosecutions” Predicate....................516 B. The Right to Compulsory Process ..................................523 C. The Right to a Public Trial .............................................528 D. The Right to a Speedy Trial............................................533 E. The Right to Confrontation............................................538 F. The Right to Assistance of Counsel ................................541 CONCLUSION.................................................................................548 APPENDIX A: FEDERAL CRIMES AT THE TIME THE SIXTH AMENDMENT WAS RATIFIED...................................................549 * © 2008 Sanjay Chhablani. All rights reserved. ** Assistant Professor, Syracuse University College of Law. I owe a debt of gratitude to Akhil Amar, David Driesen, Keith Bybee, and Gregory -

Accessibility and the Crowded Sidewalk: Micromobility’S Impact on Public Space CYNTHIA L

Accessibility and The Crowded Sidewalk: Micromobility’s Impact on Public Space CYNTHIA L. BENNETT Carnegie Mellon University, [email protected] EMILY E. ACKERMAN Univerisity of Pittsburgh, [email protected] BONNIE FAN Carnegie Mellon University, [email protected] JEFFREY P. BIGHAM Carnegie Mellon University, [email protected] PATRICK CARRINGTON Carnegie Mellon University, [email protected] SARAH E. FOX Carnegie Mellon University, [email protected] Over the past several years, micromobility devices—small-scale, networked vehicles used to travel short distances—have begun to pervade cities, bringing promises of sustainable transportation and decreased congestion. Though proponents herald their role in offering lightweight solutions to disconnected transit, smart scooters and autonomous delivery robots increasingly occupy pedestrian pathways, reanimating tensions around the right to public space. Drawing on interviews with disabled activists, government officials, and commercial representatives, we chart how devices and policies co-evolve to fulfill municipal sustainability goals, while creating obstacles for people with disabilities whose activism has long resisted inaccessible infrastructure. We reflect on efforts to redistribute space, institute tech governance, and offer accountability to those who involuntarily encounter interventions on the ground. In studying micromobility within spatial and political context, we call for the HCI community to consider how innovation transforms as it moves out from centers of development toward peripheries of design consideration. CCS CONCEPTS • Human-centered computing~Accessibility~Empirical studies in accessibility Additional Keywords and Phrases: Micromobility, Accessibility, Activism, Governance, Public space ACM Reference Format: Cynthia L. Bennett, Emily E. Ackerman, Bonnie Fan, Jeffrey P. Bigham, Patrick Carrington, and Sarah E. Fox. 2021. Accessibility and The Crowded Sidewalk: Micromobility’s Impact on Public Space. -

St. Paul's Episcopal Church Broad Street 36 03 40 N 76 36 31 W

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church Broad Street 36 03 40 N 76 36 31 W W. D. Holmes July 22, 1842 April 26, 1908 Father Harriet Holmes March 11, 1842 July 29, 1883 Mother Eligible stone In Memory of M.J. Hollowell Wife of W.H. Hollowell November 15, 1840 January 5, 1883 In Memory of Jessie Hollowell Son of W.H. Hollowell Wife ______ Hollowell In Memory of Infant son of W.H. and M.J. Hollowell Burnice McCoy April 1, 1899 January 7, 1901 Elizabeth Arnold Jackson Wife of Jacob Wool December 21, 1852 June 17, 1914 Asleep in Jesus Penelopy McCoy August 20, 1839 May 15, 1915 James McCoy August 20, 1827 April 14, 1892 Patty June McCoy June 22, 1861 August 27, 1888 Jacob Wool August 27, 1830 December 6, 1900 In Loving Remembrance of Annie B. Wool November 8, 1870 September 5, 1887 Daughter of Jacob and Elizabeth Wool A faithful Christian devoted friend, none knew her but to love her. Asleep in Jesus. Eligible ground marker Elizabeth M.W. Moore Daughter of Augustus Minten and Elizabeth Warren Moore March 3, 1878 February 28, 1936 Judge Augustus M. Moore December 17, 1841 April 24, 1902 Our father Mary E. Moore August 11, 1839 February 12, 1903 William Edward Anderson Thompson August 6, 1869 February 16, 1924 The Lord is my rock and my fortress. God is Love. Walker Anderson Thompson October 18, 1866 February 15, 1891 Erected in loving remembrance by his aunt Mary Read Anderson. John Thompson September 6, 1860 February 6, 1879 Blessed are the pure in heart for they shall see God. -

Grappling with Race: a Textual Analysis of Race Within the Wwe

GRAPPLING WITH RACE: A TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF RACE WITHIN THE WWE BY MARQUIS J. JONES A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Communication April 2019 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Ronald L. Von Burg, PhD, Advisor Jarrod Atchison, PhD, Chair Eric K. Watts, PhD ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Ron Von Burg of the Communication Graduate School at Wake Forest University. Dr. Von Burg’s office was always open whenever I needed guidance in the completion of this thesis. He consistently allowed this paper to be my own work, but steered me in the right direction whenever he thought I needed. I would also like to thank Dr. Jarrod Atchison and Dr. Eric Watts for serving as committed members of my Graduate Thesis Committee. I truly appreciate the time and energy that was devoted into helping me complete my thesis. Finally, I must express my very profound gratitude to my parents, Marcus and Erika Jones, for providing me with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout my years of sturdy and through the process of research and writing this thesis. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. Thank you. I love you both very much. Thank you again, Marquis Jones iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………..iv Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION………………………………………………Pg. 1 Chapter 2: HISTORY OF WWE……………………………………………Pg. 15 Chapter 3: RACIALIZATION IN WWE…………………………………..Pg. 25 Chapter 4: CONCLUSION………………………………………………......Pg. -

Toward a Revitalization of the Contract Clause Richard A

The University of Chicago Law Review VOLUME 51 NUMBER 3 SUMMER 1984 0 1984 by The University of Chicago Toward a Revitalization of the Contract Clause Richard A. Epsteint The protection of economic liberties under the United States Constitution has been one of the most debated issues in our consti- tutional history.' Today the general view is that constitutional pro- tection is afforded to economic liberties only in the few cases of government action so egregious and outrageous as to transgress the narrow prohibitions of substantive due process.2 The current atti- tude took its definitive shape in the great constitutional battles over the New Deal, culminating in several important cases that sustained major legislative interference with contractual and prop- erty rights.3 The occasional Supreme Court decision hints at re- newed judicial enforcement of limitations on the legislative regula- t James Parker Hall Professor of Law, University of Chicago. This paper was originally prepared for a conference on "Economic Liberties and the Constitution," organized at the University of San Diego Law School in December, 1983, under the direction of Professors Larry Alexander and Bernard Siegan. I also presented it as a workshop paper at Boston University Law School in February, 1984. I wish to thank all the participants for their valu- able comments and criticisms. I also wish to thank David Currie, Geoffrey Miller, Geoffrey Stone, and Cass Sunstein for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article. The classic work on the subject is C. BEARD, AN EcONOPEC INTERPRETATION OF THE CONsTrruTiON OF THE UNrTED STATES (1913). -

Contradictions in the Twitter Social Factory: Reflections on Kylie

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Joanna Boehnert Contradictions in the Twitter Social Factory: Reflections on Kylie Jarrett’s Chapter 2019 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/11934 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Boehnert, Joanna: Contradictions in the Twitter Social Factory: Reflections on Kylie Jarrett’s Chapter. In: Dave Chandler, Christian Fuchs (Hg.): Digital Objects, Digital Subjects: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Capitalism, Labour and Politics in the Age of Big Data. London: University of Westminster Press 2019, S. 117– 123. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/11934. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/10.16997/book29.i Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 CHAPTER 9 Contradictions in the Twitter Social Factory : Reflections on Kylie Jarrett’s Chapter Joanna Boehnert On 2 November 2017 two of New York City’s local digital news sites, The Gothamist and DNAinfom, were shut down by owner Joe Ricketts. All articles and information generated since 2009 vanished from the sites – to be archived elsewhere in less accessible format. 115 people lost their jobs. The destruction of the news companies along with the documentation of local history was in- stigated by Ricketts as an unsubtle response to an event just one week earlier: when reporters at DNAinfo and Gothamist had voted to unionise. -

Who Is the Attorney General's Client?

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\87-3\NDL305.txt unknown Seq: 1 20-APR-12 11:03 WHO IS THE ATTORNEY GENERAL’S CLIENT? William R. Dailey, CSC* Two consecutive presidential administrations have been beset with controversies surrounding decision making in the Department of Justice, frequently arising from issues relating to the war on terrorism, but generally giving rise to accusations that the work of the Department is being unduly politicized. Much recent academic commentary has been devoted to analyzing and, typically, defending various more or less robust versions of “independence” in the Department generally and in the Attorney General in particular. This Article builds from the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Co. Accounting Oversight Board, in which the Court set forth key principles relating to the role of the President in seeing to it that the laws are faithfully executed. This Article draws upon these principles to construct a model for understanding the Attorney General’s role. Focusing on the question, “Who is the Attorney General’s client?”, the Article presumes that in the most important sense the American people are the Attorney General’s client. The Article argues, however, that that client relationship is necessarily a mediated one, with the most important mediat- ing force being the elected head of the executive branch, the President. The argument invokes historical considerations, epistemic concerns, and constitutional structure. Against a trend in recent commentary defending a robustly independent model of execu- tive branch lawyering rooted in the putative ability and obligation of executive branch lawyers to alight upon a “best view” of the law thought to have binding force even over plausible alternatives, the Article defends as legitimate and necessary a greater degree of presidential direction in the setting of legal policy. -

Official Autobiography of WWE Wrestler James KAMALA Harris Online

obHQJ [Read free] Kamala Speaks (eBook Editor's Edition): Official Autobiography of WWE wrestler James KAMALA Harris Online [obHQJ.ebook] Kamala Speaks (eBook Editor's Edition): Official Autobiography of WWE wrestler James KAMALA Harris Pdf Free James Kamala Harris, Kenny Casanova DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #389856 in eBooks 2015-12-18 2015-12-18File Name: B019JJR59Q | File size: 35.Mb James Kamala Harris, Kenny Casanova : Kamala Speaks (eBook Editor's Edition): Official Autobiography of WWE wrestler James KAMALA Harris before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Kamala Speaks (eBook Editor's Edition): Official Autobiography of WWE wrestler James KAMALA Harris: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Love this bookBy Bubba EdwardsGreat read, Kamala Speaks is easily in my top 5 favorite books.If you were ever a fan of the Ugandan Giant or if he scared the crap out of you when you were a kid. You should buy this book and read it, you won't be disappointed.2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. Kamala speaks out laud!!!!By Maximo ZaldivarGreat Book!I was amazed with this book, I am so glad Kamala had the health to make time for the book, and with all the support he got from many people and fellow wrestlers.To read page by page his career through so many years and promotions, is an epic journey for any wrestling fan.I hope the WWE really comes to their senses and inducts Kamala soon in the Hall of Fame before it is too late, he deserves it more than many who are already in there, his amazing career, his professionalism and his loyalty are enough merits.5 of 5 people found the following review helpful. -

August 2014 Member Newsletter Final Draft for Online

THE PORTS AGE Vol. I, Issue I P Summer 2014 SNews from the Babe Ruth Birthplace and Sports Legends Museum The Babe Ruth Birthplace presents INSIDE THIS ISSUE “BABE RUTH: 100 YEARS” By Patrick Dickerson Home Runs. The highest 714 all-time slugging percentage. It all began on July 11, 1914 when George Herman “Babe” Ruth began his professional career with the Boston Red Sox—the career we celebrate in our newest Celebrate Babe Ruth’s 100 year exhibition, “Babe Ruth: 100 anniversary of joining Major Years.” League Baseball with the Director Mike Gibbons and interesting facts on page 3. Board Chairman John Moag opened the exhibit on June 26 in the Babe Ruth Birthplace’s first floor gallery, featuring both collection favorites and never- before-seen pieces. Babe’s 60 home run season bat returns to public display along with his 1914 Orioles’ rookie card, his catholic rosary that he carried to his death in 1948, and the original marriage certificate from his wedding to Helen Kids, look at the Kids Corner on Woodford in Ellicott City, Maryland. They bring to life both Ruth page 4 for a special the professional and Ruth the person, from his beginnings with Jack Babe Ruth puzzle. Dunn’s Baltimore Orioles to his final days battling cancer. The “Babe” loved to tell a story. Visitors to our new exhibit can hear those stories from Ruth himself through interactive historic audio recordings. Listen up as Babe shares his memories of 1914 spring training in Fayetteville and his larger-than-life slugging records. Another Ruth memory comes to life Just down the hall in our acclaimed film, “The Star-Spangled Banner in Sports,” winner of the 2013 International Sports Heritage Association Communications Award.