Some Notes on the Equation of Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions

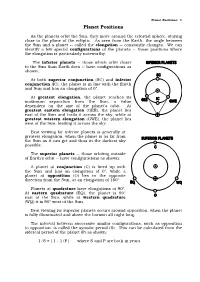

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions As the planets orbit the Sun, they move around the celestial sphere, staying close to the plane of the ecliptic. As seen from the Earth, the angle between the Sun and a planet -- called the elongation -- constantly changes. We can identify a few special configurations of the planets -- those positions where the elongation is particularly noteworthy. The inferior planets -- those which orbit closer INFERIOR PLANETS to the Sun than Earth does -- have configurations as shown: SC At both superior conjunction (SC) and inferior conjunction (IC), the planet is in line with the Earth and Sun and has an elongation of 0°. At greatest elongation, the planet reaches its IC maximum separation from the Sun, a value GEE GWE dependent on the size of the planet's orbit. At greatest eastern elongation (GEE), the planet lies east of the Sun and trails it across the sky, while at greatest western elongation (GWE), the planet lies west of the Sun, leading it across the sky. Best viewing for inferior planets is generally at greatest elongation, when the planet is as far from SUPERIOR PLANETS the Sun as it can get and thus in the darkest sky possible. C The superior planets -- those orbiting outside of Earth's orbit -- have configurations as shown: A planet at conjunction (C) is lined up with the Sun and has an elongation of 0°, while a planet at opposition (O) lies in the opposite direction from the Sun, at an elongation of 180°. EQ WQ Planets at quadrature have elongations of 90°. -

Captain Vancouver, Longitude Errors, 1792

Context: Captain Vancouver, longitude errors, 1792 Citation: Doe N.A., Captain Vancouver’s longitudes, 1792, Journal of Navigation, 48(3), pp.374-5, September 1995. Copyright restrictions: Please refer to Journal of Navigation for reproduction permission. Errors and omissions: None. Later references: None. Date posted: September 28, 2008. Author: Nick Doe, 1787 El Verano Drive, Gabriola, BC, Canada V0R 1X6 Phone: 250-247-7858, FAX: 250-247-7859 E-mail: [email protected] Captain Vancouver's Longitudes – 1792 Nicholas A. Doe (White Rock, B.C., Canada) 1. Introduction. Captain George Vancouver's survey of the North Pacific coast of America has been characterized as being among the most distinguished work of its kind ever done. For three summers, he and his men worked from dawn to dusk, exploring the many inlets of the coastal mountains, any one of which, according to the theoretical geographers of the time, might have provided a long-sought-for passage to the Atlantic Ocean. Vancouver returned to England in poor health,1 but with the help of his brother John, he managed to complete his charts and most of the book describing his voyage before he died in 1798.2 He was not popular with the British Establishment, and after his death, all of his notes and personal papers were lost, as were the logs and journals of several of his officers. Vancouver's voyage came at an interesting time of transition in the technology for determining longitude at sea.3 Even though he had died sixteen years earlier, John Harrison's long struggle to convince the Board of Longitude that marine chronometers were the answer was not quite over. -

Sun Tool Options

Sun Study Tools Sophomore Architecture Studio: Lighting Lecture 1: • Introduction to Daylight (part 1) • Survey of the Color Spectrum • Making Light • Controlling Light Lecture 2: • Daylight (part 2) • Design Tools to study Solar Design • Architectural Applications Lecture 3: • Light in Architecture • Lighting Design Strategies Sun Tool Options 1. Paper and Pencil 2. Build a Model 3. Use a Computer The first step to any of these options is to define…. Where is the site? 1 2 Sun Study Tools North Latitude and Longitude South Longitude Latitude Longitude Sun Study Tools North America Latitude 3 United States e ud tit La Sun Study Tools New York 72w 44n 42n Site Location The site location is specified by a latitude l and a longitude L. Latitudes and longitudes may be found in any standard atlas or almanac. Chart shows the latitudes and longitudes of some North American cities. Conventions used in expressing latitudes are: Positive = northern hemisphere Negative = southern hemisphere Conventions used in expressing longitudes are: Positive = west of prime meridian (Greenwich, United Kingdom) Latitude and Longitude of Some North American Cities Negative = east of prime meridian 4 Sun Study Tools Solar Path Suns Position The position of the sun is specified by the solar altitude and solar azimuth and is a function of site latitude, solar time, and solar declination. 5 Sun Study Tools Suns Position The rotation of the earth about its axis, as well as its revolution about the sun, produces an apparent motion of the sun with respect to any point on the altitude earth's surface. The position of the sun with respect to such a point is expressed in terms of two angles: azimuth The sun's position in terms of solar altitude (a ) and azimuth (a ) solar azimuth, which is the t s with respect to the cardinal points of the compass. -

Equatorial and Cartesian Coordinates • Consider the Unit Sphere (“Unit”: I.E

Coordinate Transforms Equatorial and Cartesian Coordinates • Consider the unit sphere (“unit”: i.e. declination the distance from the center of the (δ) sphere to its surface is r = 1) • Then the equatorial coordinates Equator can be transformed into Cartesian coordinates: right ascension (α) – x = cos(α) cos(δ) – y = sin(α) cos(δ) z x – z = sin(δ) y • It can be much easier to use Cartesian coordinates for some manipulations of geometry in the sky Equatorial and Cartesian Coordinates • Consider the unit sphere (“unit”: i.e. the distance y x = Rcosα from the center of the y = Rsinα α R sphere to its surface is r = 1) x Right • Then the equatorial Ascension (α) coordinates can be transformed into Cartesian coordinates: declination (δ) – x = cos(α)cos(δ) z r = 1 – y = sin(α)cos(δ) δ R = rcosδ R – z = sin(δ) z = rsinδ Precession • Because the Earth is not a perfect sphere, it wobbles as it spins around its axis • This effect is known as precession • The equatorial coordinate system relies on the idea that the Earth rotates such that only Right Ascension, and not declination, is a time-dependent coordinate The effects of Precession • Currently, the star Polaris is the North Star (it lies roughly above the Earth’s North Pole at δ = 90oN) • But, over the course of about 26,000 years a variety of different points in the sky will truly be at δ = 90oN • The declination coordinate is time-dependent albeit on very long timescales • A precise astronomical coordinate system must account for this effect Equatorial coordinates and equinoxes • To account -

Leap Second - Wikipedia

Leap second - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leap_second A leap second is a one-second adjustment that is occasionally applied to civil time Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) to keep it close to the mean solar time at Greenwich, in spite of the Earth's rotation slowdown and irregularities. UTC was introduced on 1972 January 1st, initially with a 10 second lag behind International Atomic Time (TAI). Since that date, 27 leap seconds have been inserted, the most recent on December 31, 2016 at 23:59:60 UTC, so in 2018, UTC lags behind TAI by an offset of 37 seconds.[1] The UTC time standard, which is widely used for international timekeeping and as the reference for civil time in most countries, uses the international system (SI) definition of the second. The UTC second Screenshot of the UTC clock from time.gov has been calibrated with atomic clock on the duration of the Earth's mean day of the astronomical year (https://time.gov/) during the leap second on 1900. Because the rotation of the Earth has since further slowed down, the duration of today's mean December 31, 2016. In the USA, the leap second solar day is longer (by roughly 0.001 seconds) than 24 SI hours (86,400 SI seconds). UTC would step took place at 19:00 local time on the East Coast, ahead of solar time and need adjustment even if the Earth's rotation remained constant in the future. at 16:00 local time on the West Coast, and at Therefore, if the UTC day were defined as precisely 86,400 SI seconds, the UTC time-of-day would 14:00 local time in Hawaii. -

COORDINATE TIME in the VICINITY of the EARTH D. W. Allan' and N

COORDINATE TIME IN THE VICINITY OF THE EARTH D. W. Allan’ and N. Ashby’ 1. Time and Frequency Division, National Bureau of Standards Boulder, Colorado 80303 2. Department of Physics, Campus Box 390 University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado 80309 ABSTRACT. Atomic clock accuracies continue to improve rapidly, requir- ing the inclusion of general relativity for unambiguous time and fre- quency clock comparisons. Atomic clocks are now placed on space vehi- cles and there are many new applications of time and frequency metrology. This paper addresses theoretical and practical limitations in the accuracy of atomic clock comparisons arising from relativity, and demonstrates that accuracies of time and frequency comparison can approach a few picoseconds and a few parts in respectively. 1. INTRODUCTION Recent experience has shown that the accuracy of atomic clocks has improved by about an order of magnitude every seven years. It has therefore been necessary to include relativistic effects in the reali- zation of state-of-the-art time and frequency comparisons for at least the last decade. There is a growing need for agreement about proce- dures for incorporating relativistic effects in all disciplines which use modern time and frequency metrology techniques. The areas of need include sophisticated communication and navigation systems and funda- mental areas of research such as geodesy and radio astrometry. Significant progress has recently been made in arriving at defini- tions €or coordinate time that are practical, and in experimental veri- fication of the self-consistency of these procedures. International Atomic Time (TAI) and Universal Coordinated Time (UTC) have been defin- ed as coordinate time scales to assist in the unambiguous comparison of time and frequency in the vicinity of the Earth. -

Equation of Time — Problem in Astronomy M

This paper was awarded in the II International Competition (1993/94) "First Step to Nobel Prize in Physics" and published in the competition proceedings (Acta Phys. Pol. A 88 Supplement, S-49 (1995)). The paper is reproduced here due to kind agreement of the Editorial Board of "Acta Physica Polonica A". EQUATION OF TIME | PROBLEM IN ASTRONOMY M. Muller¨ Gymnasium M¨unchenstein, Grellingerstrasse 5, 4142 M¨unchenstein, Switzerland Abstract The apparent solar motion is not uniform and the length of a solar day is not constant throughout a year. The difference between apparent solar time and mean (regular) solar time is called the equation of time. Two well-known features of our solar system lie at the basis of the periodic irregularities in the solar motion. The angular velocity of the earth relative to the sun varies periodically in the course of a year. The plane of the orbit of the earth is inclined with respect to the equatorial plane. Therefore, the angular velocity of the relative motion has to be projected from the ecliptic onto the equatorial plane before incorporating it into the measurement of time. The math- ematical expression of the projection factor for ecliptic angular velocities yields an oscillating function with two periods per year. The difference between the extreme values of the equation of time is about half an hour. The response of the equation of time to a variation of its key parameters is analyzed. In order to visualize factors contributing to the equation of time a model has been constructed which accounts for the elliptical orbit of the earth, the periodically changing angular velocity, and the inclined axis of the earth. -

Obliquity Variability of a Potentially Habitable Early Venus

ASTROBIOLOGY Volume 16, Number 7, 2016 Research Articles ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/ast.2015.1427 Obliquity Variability of a Potentially Habitable Early Venus Jason W. Barnes,1 Billy Quarles,2,3 Jack J. Lissauer,2 John Chambers,4 and Matthew M. Hedman1 Abstract Venus currently rotates slowly, with its spin controlled by solid-body and atmospheric thermal tides. However, conditions may have been far different 4 billion years ago, when the Sun was fainter and most of the carbon within Venus could have been in solid form, implying a low-mass atmosphere. We investigate how the obliquity would have varied for a hypothetical rapidly rotating Early Venus. The obliquity variation structure of an ensemble of hypothetical Early Venuses is simpler than that Earth would have if it lacked its large moon (Lissauer et al., 2012), having just one primary chaotic regime at high prograde obliquities. We note an unexpected long-term variability of up to –7° for retrograde Venuses. Low-obliquity Venuses show very low total obliquity variability over billion-year timescales—comparable to that of the real Moon-influenced Earth. Key Words: Planets and satellites—Venus. Astrobiology 16, 487–499. 1. Introduction Perhaps paradoxically, large-amplitude obliquity varia- tions can also act to favor a planet’s overall habitability. he obliquity C—defined as the angle between a plan- Low values of obliquity can initiate polar glaciations that Tet’s rotational angular momentum and its orbital angular can, in the right conditions, expand equatorward to en- momentum—is a fundamental dynamical property of a pla- velop an entire planet like the ill-fated ice-planet Hoth in net. -

Activity 3 How Do Earth's Orbital Variations Affect Climate?

CS_Ch12_ClimateChange 3/1/2005 4:56 PM Page 761 Activity 3 How Do Earth’s Orbital Variations Affect Climate? Activity 3 How Do Earth’s Orbital Variations Affect Climate? Goals Think about It In this activity you will: When it is winter in New York, it is summer in Australia. • Understand that Earth has an axial tilt of about 23 1/2°. • Why are the seasons reversed in the Northern and • Use a globe to model the Southern Hemispheres? seasons on Earth. • Investigate and understand What do you think? Write your thoughts in your EarthComm the cause of the seasons in notebook. Be prepared to discuss your responses with your small relation to the axial tilt of group and the class. the Earth. • Understand that the shape of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun is an ellipse and that this shape influences climate. • Understand that insolation to the Earth varies as the inverse square of the distance to the Sun. 761 Coordinated Science for the 21st Century CS_Ch12_ClimateChange 3/1/2005 4:56 PM Page 762 Climate Change Investigate Part A: What Causes the Seasons? Now, mark off 10° increments An Experiment on Paper starting from the Equator and going to the poles. You should have eight 1. In your notebook, draw a circle about marks between the Equator and pole 10 cm in diameter in the center of your for each quadrant of the Earth. Use a page. This circle represents the Earth. straight edge to draw black lines that Add the Earth’s axis of rotation, the connect the marks opposite one Equator, and lines of latitude, as another on the circle, making lines shown in the diagram and described that are parallel to the Equator. -

Lecture 6: Where Is the Sun?

4.430 Daylighting Massachusetts Institute of Technology Christoph Reinhart Department of Architecture 4.430 Where is the sun? Building Technology Program Goals for This Week Where is the sun? Designing Static Shading Systems MIT 4.430 Daylighting, Instructor C Reinhart 1 1 MISC Meeting on group projects Reduce HDR image size via pfilt –x 800 –y 550 filne_name_large.pic > filename_small>.pic Note: pfilt is a Radiance program. You can find further info on pfilt by googeling: “pfilt Radiance” MIT 4.430 Daylighting, Instructor C Reinhart 2 2 Daylight Factor Hand Calculation Mean Daylight Factor according to Lynes Reinhart & LoVerso, Lighting Research & Technology (2010) Move into the building, design the facade openings, room dimensions and depth of the daylit area. Determine the required glazing area using the Lynes formula. A glazing = required glazing area A total = overall interior surface area (not floor area!) R mean = area-weighted mean surface reflectance vis = visual transmittance of glazing units = sun angle 3 ‘Validation’ of Daylight Factor Formula Reinhart & LoVerso, Lighting Research & Technology (2010) Graph of mean daylighting factor according to Lynes formula v. Radiance removed due to copyright restrictions. Source: Figure 5 in Reinhart, C. F., and V. R. M. LoVerso. "A Rules of Thumb Based Design Sequence for Diffuse Daylight." Lighting Research and Technology 42, no. 1 (2010): 7-32. Comparison to Radiance simulations for 2304 spaces. Quality control for simulations. LEED 2.2 Glazing Factor Formula Graph of mean daylighting factor according to LEED 2.2 v. Radiance removed due to copyright restrictions. Source: Figure 11 in Reinhart, C. F., and V. -

Section 2 How Do Earth's Orbital Variations Affect Global Climate?

Chapter 6 Global Climate Change Section 2 Ho w Do Earth’s Orbital Variations Affect Global Climate? What Do You See? Learning Outcomes In this section, you will Learning• GoalsText Outcomes Think About It In this section, you will When it is winter in New York, it is summer in Australia. • Understandthat Earth has an • Why are the seasons reversed in the Northern and axial tilt of about 23.5°. Southern Hemispheres? • Usea globe to model the seasons on Earth. Record your ideas about this question in your Geo log. Be • Investigateand understand the prepared to discuss your responses with your small group cause of the seasons in relation and the class. to the axial tilt of Earth. • Understandthat the shape of Investigate Earth’s orbit around the Sun is an ellipse, and that this shape This Investigate has five parts. In each part, you will explore influences climate. different factors that cause Earth’s seasons. • Understandthat insolation Part A: What Causes the Seasons? An Investigation on Paper to Earth varies as the inverse square of the distance to 1. Create a model of Earth by completing the following. the Sun. a) In your log, draw a circle about 10 cm in diameter in the center of your page. This circle represents Earth. 650 EarthComm EC_Natl_SE_C6.indd 650 7/13/11 9:31:54 AM Section 2 How Do Earth’s Orbital Variations Affect Global Climate? b) Add Earth’s axis of rotation, plane • Now, mark off 10° increments of orbit, the equator, and lines of starting from the equator and going latitude, as shown in the diagram, to the poles. -

Using the SFA Star Charts and Understanding the Equatorial Coordinate System

Using the SFA Star Charts and Understanding the Equatorial Coordinate System SFA Star Charts created by Dan Bruton of Stephen F. Austin State University Notes written by Don Carona of Texas A&M University Last Updated: August 17, 2020 The SFA Star Charts are four separate charts. Chart 1 is for the north celestial region and chart 4 is for the south celestial region. These notes refer to the equatorial charts, which are charts 2 & 3 combined to form one long chart. The star charts are based on the Equatorial Coordinate System, which consists of right ascension (RA), declination (DEC) and hour angle (HA). From the northern hemisphere, the equatorial charts can be used when facing south, east or west. At the bottom of the chart, you’ll notice a series of twenty-four numbers followed by the letter “h”, representing “hours”. These hour marks are right ascension (RA), which is the equivalent of celestial longitude. The same point on the 360 degree celestial sphere passes overhead every 24 hours, making each hour of right ascension equal to 1/24th of a circle, or 15 degrees. Each degree of sky, therefore, moves past a stationary point in four minutes. Each hour of right ascension moves past a stationary point in one hour. Every tick mark between the hour marks on the equatorial charts is equal to 5 minutes. Right ascension is noted in ( h ) hours, ( m ) minutes, and ( s ) seconds. The bright star, Antares, in the constellation Scorpius. is located at RA 16h 29m 30s. At the left and right edges of the chart, you will find numbers marked in degrees (°) and being either positive (+) or negative(-).