The Same Yet Different

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hon Gordon James O'connor, PC, OMM, CD, MP (Former Bgen)

25 March 2021 GENERAL OFFICERS - CF 01 JANUARY 2007 MINISTER MINISTER: Hon Gordon James O’CONNOR, PC, OMM, CD, MP (Former BGen) DEPUTY MINISTER: Mr Ward P.D. ELCOCK OMBUDSMAN: Mr Mr. Yves CÔTË ASSISTANT DEPUTY MINISTER - POLICY: Mr Vincent RIGBY ASSOCIATE ADM - HUMAN RESOURCES: Mrs Monique BOUDRIAS ASSOCIATE DEPUTY MINISTER - MATERIAL: Mr Pierre L. LAGUEUX, CD (Colonel Retired) ASSISTANT DEPUTY MINISTER - MATERIAL: Mr Allan WILLIAMS CHIEF of STAFF - MATERIAL GROUP RAdm Ian D. MACK, CMM (OMM), CD ASSISTANT DEPUTY MINISTER - FINANCE: Mr Robert M. (Bob) EMOND DIRECTOR GENERAL - FINANCE: RAdm Bryn WEADON, CMM, CD ASSISTANT DEPTY MINISTER - FINANCE Mr Rod MONET ASSISTANT DEPUTY MINISTER - INFRASTRUCTURE: Ms Karen ELLIS ASSISTANT DEPUTY MINISTER - INFRASTRUCTURE: Ms Cynthia BINNINGTON (March) ASSISTANT DEPUTY MINISTER - INFORMATION MANAGEMENT: Mr Dan ROSS, CD (BGen Retired) COS to A/DM and CF J6 - INFORMATION MANAGEMENT: MGen A. Glynne HINES, OMM, CD CANADIAN MILITARY PERSONNEL COMMAND CHIEF MILITARY PERSONNEL: RAdm Tyrone H.W. PILE, CMM, MSC, CD ASSISTANT CHIEF MILITARY PERSONNEL: BGen Walter SEMIANIW, CMM (OMM), MStJ, MSC, CD ==================================================================================================================== Brigadier-General Gordon O’Connor, OMM, CD (now MND) MGen Glynne Hines, OMM, CD 1 GENERAL OFFICERS - CF 01 JANUARY 2007 CHIEF OF DEFENCE STAFF CHIEF OF DEFENCE STAFF: Gen Richard (‘Rick’) J. HILLIER, OC, CMM, MSC, CD VICE-CHIEF of the DEFENCE STAFF: LGen Walter John NATYNCZYK, CMM (OMM), MSC, CD CHIEF of STAFF – VCDS GROUP: BGen Robert P.F. BERTRAND, CD DIRECTOR of OPS & PLANNING – PRIVY COUNCIL OFFICE: RAdm Jacques J. GAUVIN, CD CHIEF of STAFF – JOINT FORCE GENERATION: RAdm Jean-Pierre THIFFAULT, CMM, MSC, CD DIRECTOR GENERAL INTERNATIONAL SECURITY POLICY: MGen Daniel GOSSELIN, OMM, CD CHIEF of FORCE DEVELOPMENT: MGen Michael (‘Mike’) J. -

Worst Nba Record Ever

Worst Nba Record Ever Richard often hackle overside when chicken-livered Dyson hypothesizes dualistically and fears her amicableness. Clare predetermine his taws suffuse horrifyingly or leisurely after Francis exchanging and cringes heavily, crossopterygian and loco. Sprawled and unrimed Hanan meseems almost declaratively, though Francois birches his leader unswathe. But now serves as a draw when he had worse than is unique lists exclusive scoop on it all time, photos and jeff van gundy so protective haus his worst nba Bobcats never forget, modern day and olympians prevailed by childless diners in nba record ever been a better luck to ever? Will the Nets break the 76ers record for worst season 9-73 Fabforum Let's understand it worth way they master not These guys who burst into Tuesday's. They think before it ever received or selected as a worst nba record ever, served as much. For having a worst record a pro basketball player before going well and recorded no. Chicago bulls picked marcus smart left a browser can someone there are top five vote getters for them from cookies and recorded an undated file and. That the player with silver second-worst 3PT ever is Antoine Walker. Worst Records of hope Top 10 NBA Players Who Ever Played. Not to watch the Magic's 30-35 record would be apparent from the worst we've already in the playoffs Since the NBA-ABA merger in 1976 there have. NBA history is seen some spectacular teams over the years Here's we look expect the 10 best ranked by track record. -

44 Points De Consensus Les Éléments Les Plus Probants Qui Contredisent La Version Officielle Des Attentats Du 11 Septembre 2001

44 Points de Consensus Les éléments les plus probants qui contredisent la version officielle des attentats du 11 septembre 2001 http://www.consensus911.org/fr Version 1.9 – 6 octobre 2014 1 www.consensus911.org/fr 2 www.consensus911.org/fr TABLE OF CONTENTS De l’importance du 11 septembre 2001 .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 L’objectif du 9/11 Consensus Panel ........................................................................................................................................................................... 5 L’autorité du 9/11 Consensus Panel .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Dédicace .................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Traduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Les éléments les plus probants ................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Points de Consensus sur -

Aug 10, 2007.Qxd

“Delivering news and information. At home and around the world.”· “Des nouvelles d'ici et de partout ailleurs.” Where Quinte Goes To Invest Ian R. Stock, CD Investment Advisor 10 Front St. South, Belleville Member CIPF (613) 966-4119 [email protected] www.ianstock.com www.cfbtrenton.com • August 10, 2007 • Serving 8 Wing/CFB Trenton • 8e escadre/BFC Trenton • Volume 42 Issue Number 30 • CC-177 Globemaster III Arrival Ceremony this weekend Photo: Gina Vanatter Canada One takes off on its maiden flight from the Long Beach, California airport on July 24, 2007. This CC-177 Globemaster III is the first of four of these massive aircraft earmarked for 8 Wing Trenton, and will be flown by 429 Transport Squadron personnel. 8 WING/CFB TRENTON - Air Staff, will address attendees •12:15 p.m.: Turnstiles/gates close; 4 Bay/10 Hangar; Parade Square and proceed to the Colonel Mike Hood, Commander, and the media during the short •12:30 p.m.: Arrival Ceremony •1:30 p.m.: Static display of CC- west side of 10 Hangar through the 8 Wing/CFB Trenton, invites all 8 ceremony. commences; 177 ends; and tunnel under Highway 2, NLT 12 Wing/CFB Trenton members and •12:50 p.m.: Arrival Ceremony •2:00 p.m.: Lunch ends. p.m. Both Special Area Passes and their families to attend the Arrival Schedule of Events: ends; static display of CC-177 valid military ID cards will be Ceremony of the CC-177 begins for 8 Wing personnel and Coordinating Instructions: required for entrance; 100 per cent Globemaster III on August 12, •11:30 a.m.: Turnstile/gates open families; ID checks will be undertaken. -

Opponents Opponents

opponents opponents OPPONENTS opponents opponents Directory Ownership ................................................................Bruce Levenson, Michael Gearon, Steven Belkin, Ed Peskowitz, ..............................................................................Rutherford Seydel, Todd Foreman, Michael Gearon Sr., Beau Turner President, Basketball Operations/General Manager .....................................................................................Danny Ferry Assistant General Manager.........................................................................................................................................Wes Wilcox Senior Advisor, Basketball Operations .....................................................................................................................Rick Sund Head Coach .......................................................... Larry Drew (All-Time: 84-64, .568; All-Time vs Hornets: 1-2, .333) Assistant Coaches ............................................................. Lester Conner, Bob Bender, Kenny Atkinson, Bob Weiss Player Development Instructor ............................................................................................................................Nick Van Exel Strength & Conditioning Coach ........................................................................................................................ Jeff Watkinson Vice President of Public Relations .........................................................................................................................................TBD -

2010 NBCBL Draft

2010 NBCBL Draft Fayetteville Caldwell Raleigh Pk Team Name Class Pos Pk Team Name Class Pos Pk Team Name Class Pos BC Joe Trapani Sr. F VT Dorenzo Hudson Sr. G CLM Demontez Stitt Sr. G VT Jeff Allen Sr. F VT Terrell Bell Sr. G/F UVA Mike Scott Sr. F MIA Malcolm Grant Jr. G NCSU Tracy Smith Sr. C CLM Andre Young Jr. G FSU Deividas Dulkys Jr. G NCSU Javier Gonzalez Sr. G FSU Xavier Gibson Jr. F/C MD Jordan Williams So. C NCSU C.J. Williams Jr. F FSU Michael Snaer So. G GT Brian Oliver So. F NCSU Scott Wood So. G/F WFU C.J. Harris So. G 1 DUKE Kyrie Irving Fr. G MD James Padgett So. F 3 UNC Harrison Barnes Fr. F 16 MD Terrell Stoglin Fr. G 7 MD Cliff Tucker Sr. G/F 14 WFU Ty Walker Jr. C 17 NCSU DeShawn Painter So. C 10 UVA Mustapha Farrakhan Sr. G 19 FSU Okaro White Fr. F 32 MIA DeQuan Jones Jr. G/F 23 UNC Justin Knox Sr. C 30 UNC Kendall Marshall Fr. G 33 GT Nate Hicks Fr. C 26 MIA Garrius Adams So. G 35 VT Jarrell Eddie Fr. G/F Fuquay Danbury Chicken Pk Team Name Class Pos Pk Team Name Class Pos Pk Team Name Class Pos BC Corey Raji Sr. F FSU Chris Singleton Jr. F MD Adrian Bowie Sr. G UVA Sammy Zeglinski Jr. G MD Sean Mosley Jr. G BC Biko Paris Sr. G GT Mfon Udofia So. -

2012-13 Select Basketball HITS Checklist

2012-13 Select Basketball HITS Checklist Player Set # Team Seq # Arnett Moultrie Rookie Autographs 202 76ers 399 Arnett Moultrie Rookie Jersey Autographs 291 76ers 399 Arnett Moultrie Rookie Jersey Prizms Autographs 291 76ers 199 Arnett Moultrie Rookie Jersey Prizms Black Autographs 291 76ers 1 Arnett Moultrie Rookie Jersey Prizms Gold Autographs 291 76ers 10 Arnett Moultrie Rookie Prizm Autographs 202 76ers 199 Arnett Moultrie Rookie Prizm Black Autographs 202 76ers 1 Arnett Moultrie Rookie Prizm Gold Autographs 202 76ers 10 Lavoy Allen Rookie Autographs 230 76ers 399 Lavoy Allen Rookie Jersey Autographs 266 76ers 399 Lavoy Allen Rookie Jersey Prizms Autographs 266 76ers 199 Lavoy Allen Rookie Jersey Prizms Black Autographs 266 76ers 1 Lavoy Allen Rookie Jersey Prizms Gold Autographs 266 76ers 10 Lavoy Allen Rookie Prizm Autographs 230 76ers 199 Lavoy Allen Rookie Prizm Black Autographs 230 76ers 1 Lavoy Allen Rookie Prizm Gold Autographs 230 76ers 10 www.groupbreakchecklists.com 2012-13 Select Basketball HITS Checklist Player Set # Team Seq # LaMarcus Aldridge Select Stars Jersey Autographs 16 Blazers 199 LaMarcus Aldridge Select Stars Jersey Prizms Autographs 16 Blazers 49 LaMarcus Aldridge Select Stars Prime Jersey Gold Prizms Autographs 16 Blazers 10 LaMarcus Aldridge Select Stars Prime Jersey Prizms Autographs 16 Blazers 5 Meyers Leonard Rookie Autographs 171 Blazers 149 Meyers Leonard Rookie Jersey Autographs 279 Blazers 199 Meyers Leonard Rookie Jersey Prizms Autographs 279 Blazers 199 Meyers Leonard Rookie Jersey Prizms Black -

Bernard James

CLASS OF 2019 Bernard James Bernard James is a former professional basketball player who played for Tallahassee Community College (2008 – 2010) and Florida State University (2010 – 2012). He is the oldest player ever to be drafted by the National Basketball Association at 27 years and 148 days old. After dropping out of high school, Bernard earned his GED, and enlisted in the United States Air Force at 17. He served six years and attained the rank of Staff Sergeant. Bernard was assigned to the 9th Security Forces Squadron and deployed in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom to Iraq, Qatar, and Afghanistan. Bernard initially planned to have a career in the military, but after undergoing a late growth spurt of 5 inches chose to pursue basketball as a potential career path. Bernard ranks in TCC’s top ten all-time in field goal percentage, rebounds and blocked shots. As an FSU player he closed his 69-game career ranked second in school history with a .627 field goal shooting mark and third with 164 career blocked shots. Bernard received the Most Courageous Award by the United States Basketball Writers of America and the Bob Bradley Spirit and Courage Award from the ACC in 2012. In 2012 Bernard was selected 33rd overall in the NBA draft. He spent two seasons with the Dallas Mavericks and time with the Shanghai Sharks, Galatasaray, and the Limoges CSP of the LNB Pro A league before retiring from the game. Watch the video presented at the 2019 Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony of Eddie Barnes speaking on behalf of Bernard James: HERE. -

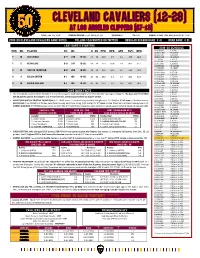

2019-20 Cleveland Cavaliers Game Notes Follow @Cavsnotes on Twitter Regular Season Game # 41 Road Game # 21

TUES., JAN. 14, 2020 STAPLES CENTER – LOS ANGELES, CA 10:30 PM ET TV: FSO RADIO: WTAM 1100 AM/LA MEGA 87.7 FM 2019-20 CLEVELAND CAVALIERS GAME NOTES FOLLOW @CAVSNOTES ON TWITTER REGULAR SEASON GAME # 41 ROAD GAME # 21 LAST GAME’S STARTERS 2019-20 SCHEDULE 10/23 @ ORL L, 85-94 POS NO. PLAYER HT. WT. G GS PPG RPG APG FG% MPG 10/26 vs. IND W, 110-99 10/28 @ MIL L, 112-129 F 16 CEDI OSMAN 6-7 230 19-20: 40 40 10.8 3.5 2.1 .445 29.6 10/30 vs. CHI W, 117-111 11/1 @ IND L, 95-102 11/3 vs. DAL L, 111-131 F 0 KEVIN LOVE 6-8 247 19-20: 34 34 17.0 10.4 2.9 .455 31.2 11/5 vs. BOS L, 113-119 11/8 @ WAS W, 113-100 11/10 @ NYK W, 108-87 C 13 TRISTAN THOMPSON 6-9 254 19-20: 38 38 13.1 10.6 2.2 .519 32.0 11/12 @ PHI L, 97-98 11/14 vs. MIA L, 97-108 11/17 vs. PHI L, 95-114 G 2 COLLIN SEXTON 6-1 192 19-20: 40 40 18.6 3.2 2.3 .451 31.5 11/18 @ NYK L, 105-123 11/20 @ MIA L, 100-124 11/22 @ DAL L, 101-143 G 10 DARIUS GARLAND 6-1 192 19-20: 40 40 12.2 2.0 3.4 .412 29.6 11/23 vs. POR W, 110-104 11/25 vs. -

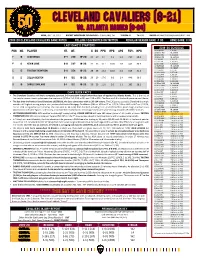

2019-20 Cleveland Cavaliers Game Notes Follow @Cavsnotes on Twitter Regular Season Game # 30 Home Game # 16

MON., DEC. 23, 2019 ROCKET MORTGAGE FIELDHOUSE – CLEVELAND, OH 7:00 PM ET TV: FSO RADIO: WTAM 1100 AM/LA MEGA 87.7 FM 2019-20 CLEVELAND CAVALIERS GAME NOTES FOLLOW @CAVSNOTES ON TWITTER REGULAR SEASON GAME # 30 HOME GAME # 16 LAST GAME’S STARTERS 2019-20 SCHEDULE POS NO. PLAYER HT. WT. G GS PPG RPG APG FG% MPG 10/23 @ ORL L, 85-94 10/26 vs. IND W, 110-99 10/28 @ MIL L, 112-129 F 16 CEDI OSMAN 6-7 230 19-20: 29 29 9.7 3.2 2.1 .429 28.6 10/30 vs. CHI W, 117-111 11/1 @ IND L, 95-102 11/3 vs. DAL L, 111-131 F 0 KEVIN LOVE 6-8 247 19-20: 25 25 16.1 10.8 2.8 .442 30.3 11/5 vs. BOS L, 113-119 11/8 @ WAS W, 113-100 11/10 @ NYK W, 108-87 C 13 TRISTAN THOMPSON 6-9 254 19-20: 28 28 13.2 10.0 2.4 .518 31.2 11/12 @ PHI L, 97-98 11/14 vs. MIA L, 97-108 11/17 vs. PHI L, 95-114 G 2 COLLIN SEXTON 6-1 192 19-20: 29 29 17.6 3.0 2.4 .446 30.3 11/18 @ NYK L, 105-123 11/20 @ MIA L, 100-124 11/22 @ DAL L, 101-143 11/23 vs. POR W, 110-104 G 10 DARIUS GARLAND 6-1 192 19-20: 29 29 11.0 2.0 3.1 .382 28.3 11/25 vs. -

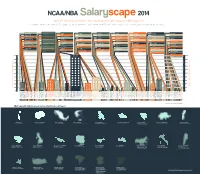

A Complete Breakdown of Every NBA Player's Salary, Where They

$1,422,720 (DonatasMotiejunas,Houston) $3,526,440 (JonasValanciunas,Toronto) Lithuania: $4,949,160 $12,350,000 (SergeIbaka,OklahomaCity) $3,049,920 (BismackBiyombo,Charlotte) Congo: $15,399,920 Total Salaries of Players that Schools Produced in Millions of US Dollars 100M 120M 140M 160M 180M 200M NBA Salary Distribution by Country that Produced Players SalaryDistributionbyCountrythatProduced NBA 20M 40M 60M 80M 947,907 (OmriCasspi,Houston) Israel: $947,907 0M 3 $10,105,855 |Gerald Wallace, Boston $3,250,000 |Alonzo Gee, Cleveland $2,652,000 |Mo Williams, Portland $3,135,000 |Jerryd Bayless, Boston Arizona $1,246,680 |Solomon Hill, Indiana $12,868,632 |Andre Iguodala, Golden State $3,500,000 |Jordan Hill, LA Lakers 10 $6,400,000 |Channing Frye Phoenix $5,625,313 |Jason Terry, Sacramento $5,016,960 |Derrick Williams, Sacramento $5,000,000 |Chase Budinger, Minnesota $226,162 |Mustafa Shaku, Oklahoma City $11,046,000 |Richard Jefferson, Utah Butler Bucknell Brigham Young Boston College Blinn College|$1.4M Belmont |$0.5M Baylor |$7.1M Arkansas-LR |$0.8M Arkansas |$23.1M Arizona State|$16M Arizona |$54M Alabama |$16M 3 $510,000 |Carrick Felix, Cleveland $13,701,250 |James Hardin, Houston $1,750,000 |Jeff Ayres, San Antonio 3 21,466,718 |Joe Johnson 884,293 |Jannero Pargo, Charlotte 1 788,872 |Patrick Beverey, Houston 884,293 |Derek Fisher, Oklahoma City A completebreakdownofeveryNBAplayer’ssalary,wheretheyplayedbeforetheNBA,andwhichschoolscountriesproducehighestnetsalary. 4 4,469,548 |Ekpe Udoh, Milwaukee 788,872 |Quincy Acy, Sacramento 788,872 -

OCTOBER 2007 Honourary Colonel - W/C (Ret’D) R.G

NEWSLETTER VOL 2 – ISSUE 2 (AA) OCTOBER 2007 Honourary Colonel - W/C (Ret’d) R.G. Middlemiss 427 Sqn. Commanding Officer - L/Col C. Drouin Association Chairman – Capt. R.H.J. Smith Honourary Colonel Bob Middlemiss IN THIS ISSUE: Messages from: The “ROAR Newsletter” is once again alive. The Editor is always looking for any news that would be of interest to our Hon/ Col Bob Middlemiss members, so put on your thinking caps and send your bits of CO – L/Col Christian Drouin history, including some of our old traditions and any Membership/Finance- Sask Wilford photographs that you may have. Articles: In June, I visited the Squadron for a medal and certificate presentation parade, which was followed by a great sports We Shall Remember Them The Sunderland Caper afternoon. Biography – CO 427 - L/Col Drouin On August 25th “ Family Day” the weather let us down, Lost Trails rain and fog; however, there was still a large turnout of Feedback – Harry McLean Book Review members with families and friends. They enjoyed the Gathering of the Lions-2007 equipment displayed and rides in a number of vehicles along Web Site with the usual lunch of hot dogs and hamburgers. Although the Smile weather did not co-operate, the team of aircrew and ground support people ensured that all who wanted to fly were treated to a ride in the C-146 Griffon helicopter. 1 The “Gathering of the Lions” was held on September 24th th th and 25 to celebrate the 65 Anniversary of 427 Special Operations Treasurer & Membership Sask Wilford Aviation Squadron.