Audience Structure and the Failure of Institutional Entrepreneurship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Post-Industrial Engineering: Computer Science and the Organization of White-Collar Work, 1945-1975 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4s3388sm Author Mamo, Andrew Benedict Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Post-Industrial Engineering: Computer Science and the Organization of White-Collar Work, 1945-1975 by Andrew Benedict Mamo A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Cathryn Carson, Chair Professor David Hollinger Professor David Winickoff Spring 2011 Post-Industrial Engineering: Computer Science and the Organization of White-Collar Work, 1945-1975 © 2011 by Andrew Benedict Mamo Abstract Post-Industrial Engineering: Computer Science and the Organization of White-Collar Work, 1945-1975 by Andrew Benedict Mamo Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Cathryn Carson, Chair The development of computing after the Second World War involved a fundamental reassessment of information, communication, knowledge — and work. No merely technical project, it was prompted in part by the challenges of industrial automation and the shift toward white-collar work in mid-century America. This dissertation therefore seeks out the connections between technical research projects and organization-theory analyses of industrial management in the Cold War years. Rather than positing either a model of technological determinism or one of social construction, it gives a more nuanced description by treating the dynamics as one of constant social and technological co-evolution. -

Machines Who Think

Machines Who Think FrontMatter.pmd 1 1/30/2004, 12:15 PM Other books by the author: Familiar Relations (novel) Working to the End (novel) The Fifth Generation (with Edward A. Feigenbaum) The Universal Machine The Rise of the Expert Company (with Edward A. Feigenbaum and H. Penny Nii) Aaron’s Code The Futures of Women (with Nancy Ramsey) FrontMatter.pmd 2 1/30/2004, 12:15 PM Machines Who Think A Personal Inquiry into the History and Prospects of Artificial Intelligence Pamela McCorduck A K Peters, Ltd. Natick, Massachusetts FrontMatter.pmd 3 1/30/2004, 12:15 PM Editorial, Sales, and Customer Service Office A K Peters, Ltd. 63 South Avenue Natick, MA 01760 www.akpeters.com Copyright © 2004 by A K Peters, Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. “Artificial Intelligence”. Copyright (c) 1993, 1967, 1963 by Adrienne Rich, from COLLECTED EARLY POEMS: 1950-1970 by Adrienne Rich. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McCorduck, Pamela, 1940- Machines who think : a personal inquiry into the history and prospects of artificial intelligence / Pamela McCorduck.–2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-56881-205-1 1. Artificial intelligence–History. I. Title. Q335.M23 2003 006.3’09–dc21 2003051791 Printed in Canada 08 07 06 05 04 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 FrontMatter.pmd 4 1/30/2004, 12:43 PM To W.J.M., whose energetic curiosity was always a delight and, at the last, a wonder. -

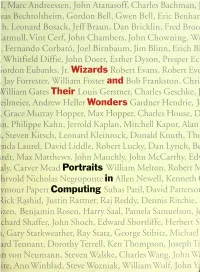

Wizards and Their Wonders: Portraits in Computing

. Atanasoff, 1, Marc Andreessen, John Charles Bachman, J eas Bechtolsheim, Gordon Bell, Gwen Bell, Eric Benhar :h, Leonard Bosack, Jeff Braun, Dan Bricklin, Fred Broo ]atmull, Vint Cerf, John Chambers, John Chowning, W< Fernando Corbato, Joel Birnbaum, Jim Blinn, Erich Bl , Whitfield Diffie, John Doerr, Esther Dyson, Presper Ec iordon Eubanks, Jr. Wizards Robert Evans, Robert Eve , Jay Forrester, William Foster and Bob Frankston, Chri William Gates Their Louis Gerstner, Charles Geschke, J eilmeier, Andrew Heller Wonders Gardner Hendrie, J , Grace Murray Hopper, Max Hopper, Charles House, D in, Philippe Kahn, Jerrold Kaplan, Mitchell Kapor, Alan i, Steven Kirsch, Leonard Kleinrock, Donald Knuth, The *nda Laurel, David Liddle, Robert Lucky, Dan Lynch, B^ irdt, Max Matthews, John Mauchly, John McCarthy, Ed^ aly, Carver Mead Portraits William Melton, Robert JV hrvold Nicholas Negroponte in Allen Newell, Kenneth < ymour Papert Computing Suhas Patil, David Pattersoi Rick Rashid, Justin Rattner, Raj Reddy, Dennis Ritchie, izen, Benjamin Rosen, Harry Saal, Pamela Samuelson, J( chard Shaffer, John Shoch, Edward Shortliffe, Herbert S 1, Gary Starkweather, Ray Stata, George Stibitz, Michael ardTennant, Dorothy Terrell, Ken Thompson, Joseph Tr in von Neumann, Steven Walske, Charles Wang, John W ite, Ann Winblad, Steve Wozniak, William Wulf, John Yc Wizards and Their Wonders: Portraits in Computing Wizards and Their Wonders: Portraits in Computing is a tribute by The Computer Museum and the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) to the many people who made the computer come alive in this century. It is unabashedly American in slant: the people in this book were either born in the United States or have done their major work there. -

1956 and the Origins of Artificial Intelligence Computing

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Building the Second Mind: 1956 and the Origins of Artificial Intelligence Computing Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/88q1j6z3 ISBN 9781476357638 Author Skinner, Rebecca Elizabeth Publication Date 2012-05-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Building the Second Mind: 1956 and the Origins of Artificial Intelligence Computing Rebecca E. Skinner copyright 2012 by Rebecca E. Skinner ISBN 978-0-9894543-1-5 Building the Second Mind: 1956 and the Origins of Artificial Intelligence Computing Chapter .5. Preface Chapter 1. Introduction Chapter 2. The Ether of Ideas in the Thirties and the War Years Chapter 3. The New World and the New Generation in the Forties Chapter 4. The Practice of Physical Automata Chapter 5. Von Neumann, Turing, and Abstract Automata Chapter 6. Chess, Checkers, and Games Chapter 7. The Impasse at End of Cybernetic Interlude Chapter 8. Newell, Shaw, and Simon at the Rand Corporation Chapter 9. The Declaration of AI at the Dartmouth Conference Chapter 10. The Inexorable Path of Newell and Simon Chapter 11. McCarthy and Minsky begin Research at MIT Chapter 12. AI’s Detractors Before its Time Chapter 13. Conclusion: Another Pregnant Pause Chapter 14. Acknowledgements Chapter 15. Bibliography Chapter 16. Endnotes Chapter .5. Preface Introduction Building the Second Mind: 1956 and the Origins of Artificial Intelligence Computing is a history of the origins of AI. AI, the field that seeks to do things that would be considered intelligent if a human being did them, is a universal of human thought, developed over centuries. -

Edmund C. Berkeley As a Popularizer and an Educator of Computers and Symbolic Logic*

Edmund C. Berkeley as a Popularizer and an Educator of Computers and Symbolic Logic* Mai Sugimoto** Abstract This paper explores how Edmund C. Berkeley tried to instruct and popularize high - speed computers in the 1940s and 1950s and how Berkeley emphasized the connection between computers and symbolic logic. Berkeley strengthened his conviction in the significance of symbolic logic and Boolean algebra before his graduation from Harvard University and maintained this conviction for more than 30 years. Berkeley published books and articles, including Giant Brains, and sold electrical toy kits by which young boys could learn electrical circuits and their logical implications. The target audience of Berkeley covered wide range of people including those who were not making computers but were interested in using them, that is, amateur adult technology enthusiasts who enjoyed tinkering with technology or reading about science and technology, and young students. In these projects Berkeley used Shannon's paper of 1938, “A symbolic analysis of relay and switching circuits” as a theoretical basis of his conviction. Design of these kits was fine-tuned by Claude E. Shannon. Key words: Edmund C. Berkeley, symbolic logic, computer, Claude E. Shannon, Gian^ Brains 1・ Introduction This paper describes how Edmund C. Berkeley, since the 1940s and in a career span ning over twenty years, aspired to popularize and educate the public about the connection between symbolic logic and the structure of computing machinery. Berkeley was one of the founders and