Bulletin1001931smit.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEATURE TYPES Revised 2/2001 Alcove

THE CROW CANYON ARCHAEOLOGICAL CENTER FEATURE TYPES Revised 2/2001 alcove. A small auxiliary chamber in a wall, usually found in pit structures; they often adjoin the east wall of the main chamber and are substantially larger than apertures and niches. aperture. A generic term for a wall opening that cannot be defined more specifically. architectural petroglyph (not on bedrock). A petroglyph in a standing masonry wall.A piece of wall fall with a petroglyph on it should be sent in as an artifact if size permits. ashpit. A pit used primarily as a receptacle for ash removed from a hearth or firepit. In a pit structure, the ash pit is commonly oval or rectangular and is located south of the hearth or firepit. bedrock feature. A feature constructed into bedrock that does not fit any of the other feature types listed here. bell-shaped cist. A large pit whose greatest diameter is substantially larger than the diameter of its opening.A storage function is implied, but the feature may not contain any stored materials, in which case the shape of the pit is sufficient for assigning this feature type. bench surface. The surface of a wide ledge in a pit structure or kiva that usually extends around at least three-fourths of the circumference of the structure and is often divided by pilasters.The southern recess surface is also considered a bench surface segment; each bench surface segment must be recorded as a separate feature. bin: not further specified. An above-ground compartment formed by walling off a portion of a structure or courtyard other than a corner. -

Museum of New Mexico

MUSEUM OF NEW MEXICO OFFICE OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE MOGOLLON HIGHLANDS: SETTLEMENT SYSTEMS AND ADAPTATIONS edited by Yvonne R. Oakes and Dorothy A. Zamora VOLUME 6. SYNTHESIS AND CONCLUSIONS Yvonne R. Oakes Submitted by Timothy D. Maxwell Principal Investigator ARCHAEOLOGY NOTES 232 SANTA FE 1999 NEW MEXICO TABLE OF CONTENTS Figures............................................................................iii Tables............................................................................. iv VOLUME 6. SYNTHESIS AND CONCLUSIONS ARCHITECTURAL VARIATION IN MOGOLLON STRUCTURES .......................... 1 Structural Variation through Time ................................................ 1 Communal Structures......................................................... 19 CHANGING SETTLEMENT PATTERNS IN THE MOGOLLON HIGHLANDS ................ 27 Research Orientation .......................................................... 27 Methodology ................................................................ 27 Examination of Settlement Patterns .............................................. 29 Population Movements ........................................................ 35 Conclusions................................................................. 41 REGIONAL ABANDONMENT PROCESSES IN THE MOGOLLON HIGHLANDS ............ 43 Background for Studying Abandonment Processes .................................. 43 Causes of Regional Abandonment ............................................... 44 Abandonment Patterns in the Mogollon Highlands -

Native Sons and Daughters Program Manual

NATIVE SONS AND DAUGHTERS PROGRAMS® PROGRAM MANUAL National Longhouse, Ltd. National Longhouse, Ltd. 4141 Rockside Road Suite 150 Independence, OH 44131-2594 Copyright © 2007, 2014 National Longhouse, Ltd. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this manual may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, now known or hereafter invented, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, xerography, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written consent of National Longhouse, Ltd. Printed in the United States of America EDITORS: Edition 1 - Barry Yamaji National Longhouse, Native Sons And Daughters Programs, Native Dads And Sons, Native Moms And Sons, Native Moms And Daughters are registered trademarks of National Longhouse, Ltd. Native Dads And Daughters, Native Sons And Daughters, NS&D Pathfinders are servicemarks of National Longhouse TABLE of CONTENTS FOREWORD xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 Why NATIVE SONS AND DAUGHTERS® Programs? 2 What Are NATIVE SONS AND DAUGHTERS® Programs? 4 Program Format History 4 Program Overview 10 CHAPTER 2: ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES 15 Organizational Levels 16 Administrative Levels 17 National Longhouse, Ltd. 18 Regional Advisory Lodge 21 Local Longhouse 22 Nations 24 Tribes 25 CHAPTER 3: THE TRIBE 29 Preparing for a Tribe Meeting 30 Tribe Meetings 32 iii Table of Contents A Sample Tribe Meeting Procedure 34 Sample Closing Prayers 36 Tips for a Successful Meeting 37 The Parents' Meeting 38 CHAPTER 4: AWARDS, PATCHES, PROGRAM -

Lockdown in Lincoln, Part II

Lockdown in Lincoln, Part II Safety and Security in La Placita Social Studies Lesson Plan Grades 4, 5 & 7 NM Standards: Strand: History • I-A – Describe how contemporary and SWBATD comprehension of the purpose of the historical people and historic Lincoln torreon by explaining how it served as events influenced NM a defensive structure. communities and regions. • I-A1.- Identify Materials: important issues, ! computer with PowerPoint presentation events and ! projector individuals from New ! white board or screen Mexico pre-history to the present. Day 2~ Anticipatory Set: Strand: Geography: • II-A – Describe how Questions: contemporary and • “Did anyone’s house get invaded by aliens last historical people and night? If your house had been invaded by aliens, events influenced where would you have gone? New Mexico Now imagine you didn’t have a house, in fact, there • communities and were no houses or buildings around. Did you see regions. any natural features in your environment where II-E – Describe how you could have hidden from the aliens?” • economic, political, cultural and social Discussion: processes interact to shape patterns of ! Ask “if aliens did suddenly show up, what might we human populations speculate brought them here?” (Our planet’s and their resources such as water, food, minerals.) interdependence, ! Discuss how we might feel about these creatures cooperation and coming into our world and the fear that they might conflict. take the things that we need to survive. ! Explain how it is a human instinct to want to protect our basic survival necessities. Sometimes a culture will invade another culture to acquire things that aren’t necessities, such as gold or other precious metals. -

Excavations at the Green Lizard Site, Pp. 69-77

Excavations at the Green Liza_rd Site . Edgar K. Huber and William D. Lipe Introduction than Sand Canyon Pueblo, or was abandoned before the end of occupation at the larger site, does comparison of he Green Lizard site (5MT3901) is a small, Pueblo III artifacts and ecofacts from the two sites provide evidence T habitation site located in the middle reaches of Sand that may help us understand the shift from a dispersed to Canyon, approximately 1 km down canyon from Sand an aggregated settlement pattern and/or the eventual aban Canyon Pueblo (Figure 1.3). In the summers of 1987 and donment of the Sand Canyon locality? 1988, intensive excavation was carried out in the western In planning for the Green Lizard excavations, we de half of the site. A kiva, an adjacent masonry· roomblock, cided to excavate a full kiva suite (kiva and associated and the floors of several jacal structures were excavated; surface rooms) to obtain a data set fully comparable to those the midden lying to the south of these features was sampled being produced by the intensive excavations of kiva suites with test pits (Figure 6~ 1). at Sand Canyon Pueblo (Bradley, this volume; see also The Green Lizard site Was first recorded by Craw Adams 1985a; Bradley 1986, 1987, 1988a, 1990; Kleidon Canyon Center researchers in 1984 (Adams 1985a). The and Bradley 1989). layout of the site is essentially two adjacent Prudden units (Prudden 1903, 1914, 1918). It consists of two kivas, Environmental Setting approximately 20 more or less contiguous, masonry-walled surface rooms, and an extensive and reJatively deep midden The Green Lizard site is located within Sand Canyon on a deposit located to the south of the structures (Figure 6.1). -

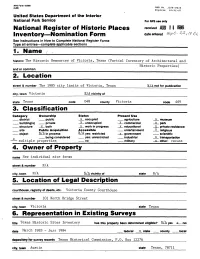

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form 1. Name

NFS Form 10-900 (3-82) 0MB Wo. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NFS use only National Register of Historic Places received AUG I I Inventory Nomination Form date entered [ri <5( See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections__________________________ 1. Name ________________________ historic The Historic Resources of Victoria, Texas (Partial Inventory of Architectural and Historic Properties) and or common____________________•__________________________ 2. Location street & number The 1985 city limits of Victoria, Texas N/A not for publication city, town Victoria N/A vicinity of state Texas code 048 county Victoria code 469 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture x museum building(s) private x unoccupied x commercial x park structure x both X work in progress x educational x private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment x religious object N/A in process N/A yes: restricted x government scientific being considered .. yes: unrestricted __ industrial x transportation multiple properties __ "no military x other: vacant 4. Owner off Property name See individual site forms street & number N/A city, town N/A I/A vicinity of state N/A 5. Location off Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Victoria County Courthouse street & number 101 North Bridge Street city, town Victoria state Texas 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Texas Historic Sites Inventory has this property been determined eligible? N/A yes z_ no date March 1983 - June 1984 federal x state county local depository for survey records Texas Historical Commission, P.O. -

Museum of New Mexico

MUSEUM OF NEW MEXICO OFFICE OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES A DATA RECOVERY PLAN FOR LA 9075, ALONG NM 53, CIBOLA COUNTY, NEW MEXICO Stephen C. Lentz Submitted by Yvonne R. Oakes Principal Investigator ARCHAEOLOGY NOTES 270 SANTA FE 2000 NEW MEXICO ADMINISTRATIVE SUMMARY The Archaeological Site Stabilization and Preservation Project (ASSAPP), Office of Archaeological Studies, Museum of New Mexico, conducted a site evaluation of LA 9075 (the La Vega site), a large multicomponent site along NM 53 in Cibola County, New Mexico, on private lands and highway right-of-way. The New Mexico State Highway and Transportation Department (NMSHTD) proposes to stabilize areas within the boundaries of the site and within the NMSHTD right-of-way that have been or may be affected by erosion. The Office of Archaeological Studies has been working under contract with the NMSHTD to identify endangered archaeological sites within highway rights-of-way. Subsequent to shoulder construction and improvement by the NMSHTD, additional cultural resources were exposed within the Museum’s project area. The OAS/ASSAPP program identified five major areas within the highway right-of-way at LA 9075 where cultural resources are threatened by erosion. These areas have been targeted for stabilization. In conjunction with the NMSHTD, District 6, the OAS proposes to conduct a data recovery program on the affected areas prior to stabilization efforts. NMSHTD Project No. TPE-7700 (14), CN 9163 MNM Project No. 41.596 (Archaeological Site Stabilization and Protection Project) Submitted in fulfillment of Joint Powers Agreement J0089-95 between the New Mexico State Highway and Transportation Department and the Office of Archaeological Studies, Museum of New Mexico. -

Navajo National Monument

UNITLDS1A1LS DLPAKTMLN1 OK 1 ML INI 1-.RIOR FOR NFS USE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Navajo National Monument AND/OR COMMON Navajo National Monument LOCATION STREET & NUMBER .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Kayenta Arizona 3;4 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Arizona AZ Coconino; Navajo oo5; 017 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X-DISTRICT X.PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE ^.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X_PARK _STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS __OBJECT _IN PROCESS X.YES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT X-SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER AGENCY National Park Service REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS (HmpplicMe) SOUthW6St STREET & NUMBER P.O. Box 728 CITY. TOWN STATE Santa Fe New Mexico VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC Coconino County Courthouse; Navajo County Courthouse STREET* NUMBER 121 E. Birch; Government Complex CITY. TOWN STATE Flagstaff; Hoi brook Arizona REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE No archaeological surveys have been done DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAt- DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X-EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED LORIGINALSITE _GOOD ' XRUINS X_ALTERED _MOV£D DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSEO DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The present appearance of the major ruins 1s close to the original, except for some fallen walls and roofs and some reconstruction and stabilization 1n the twentieth century. -

GLOSSARY of ARCHITECTURAL TERMS Revised 2/2001 Abutment

THE CROW CANYON ARCHAEOLOGICAL CENTER GLOSSARY OF ARCHITECTURAL TERMS Revised 2/2001 abutment. An intersection of walls where the stones of the two walls do not overlap or intermix; the end of one wall is built against the face of the other. basal stones. The lowest stones in the continuous face of a wall (Figure 3). cell wall. An above-ground wall constructed to block in an above-ground kiva; these walls usually form a square or rectangle, and the kiva is constructed within them.The kiva may have a separate upper lining wall, or the upper portion of the cell wall may also serve as the kiva’s upper lining wall. chinking. Small stones or sherds in the mortar joints of a masonry wall (Figure 3). tabular: relatively thin and flat, as in a piece of stone spall: a flake of stone chunk: an irregular piece of stone that is not tabular or a spall closing material. Vegetal material used in roof construction; it rests on the beams and/or shakes and is beneath the mud, daub, or loose dirt layer. courses. Horizontal rows of building stones exposed on the face of a wall. coursing. The degree of consistency with which masonry courses are laid. coursed-patterned: a fully coursed wall in which the stones have been sorted by size and/or shape; this technique produces a repeated pattern that has a decorative effect fully coursed: stones are laid in distinct rows and tend to overlap the joints of the adjacent courses, virtually eliminating running joints (Figure 3); the courses tend to be uniform in thickness semicoursed: stones are laid in somewhat distinct rows but lack consistency; stone sizes tend to be more uniform than in uncoursed walls, and running joints are less common uncoursed: stones are placed without forming distinct rows; stone sizes usually vary considerably and running joints are common cross section. -

Assessing Defensibility of Plaza-Oriented Villages in the Salinas Pueblo Province, New Mexico Daniel Mark Sumner James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current Honors College Spring 2014 Conflict on the mesa: Assessing defensibility of plaza-oriented villages in the Salinas Pueblo Province, New Mexico Daniel Mark Sumner James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019 Recommended Citation Sumner, Daniel Mark, "Conflict on the mesa: Assessing defensibility of plaza-oriented villages in the Salinas Pueblo Province, New Mexico" (2014). Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current. 486. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019/486 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Conflict on the Mesa: Assessing Defensibility of Plaza- Oriented Villages in the Salinas Pueblo Province, New Mexico _______________________ A Project Presented to the Faculty of the Undergraduate College of Arts and Letters James Madison University _______________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science _______________________ by Daniel Mark Sumner May 2012 Accepted by the faculty of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, James Madison University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science. FACULTY COMMITTEE: HONORS PROGRAM APPROVAL: Project Advisor: Julie Solometo, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Anthropology Barry Falk, Ph.D., Director, Honors Program Reader: Matthew Chamberlin, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Interdisciplinary Liberal Studies Reader: Anthony Hartshorn, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Geology & Environmental Science Dedication To my family whom I love very much: My mother, Susan; my sister, Sydney; my father, Mark; and my grandparents, Robert Stancil and Nancy Sumner. -

Historic Context & Survey Report

City of San Diego Old San Diego Community Plan Area Historic Resources Reconnaissance Survey: Historic Context & Survey Report Prepared for: City of San Diego City Planning & Community Investment Department 202 C Street, MS 5A San Diego, CA 92101 Prepared by: Galvin Preservation Associates Inc. 1611 S. Pacific Coast Hwy., Suite 104 Redondo Beach, CA 90277 310.792.2690 * 310.792.2696 (fax) DRAFT Historic Context Statement Introduction The Old San Diego Community Plan Area encompasses approximately 285 acres of relatively flat land that is bounded on the north by Interstate 8 (I-8) and Mission Valley, the west by Interstate 5 (I-5), and on south and east by the Mission Hills/Uptown hillsides. Old San Diego consists of single and multi-family uses (approximately 711 residents), and an abundant variety of tourist-oriented commercial uses (restaurant and drinking establishments, boutiques and specialty shops, jewelry stores, art stores and galleries, crafts shops, and museums). A sizeable portion of Old San Diego consists of dedicated parkland; including Old Town San Diego State Park, Presidio Park (City), Heritage Park (County), and numerous public parking facilities. There are approximately 26 designated historical sites in the Old San Diego Community Planning Area, including one historic district. Other existing public landholdings include the recently constructed Caltrans administrative and operational facility on Taylor Street. Old San Diego is also the location of a major rail transit station, primarily accommodating light rail service -

Fragments of History Compiled by Richard Field Richard W

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Transcriptions & Other Documents Special Collections Department 7-24-2012 Fragments of History compiled by Richard Field Richard W. Field El Paso County Historical Society Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.utep.edu/transcript Comments: Richard Field compiled historical features from El Paso newspapers and arranged them by the years that they describe. Recommended Citation Field, Richard W., "Fragments of History compiled by Richard Field" (2012). Transcriptions & Other Documents. Paper 2. http://digitalcommons.utep.edu/transcript/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections Department at DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transcriptions & Other Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lone Star Locals -- Vol. VI - No. 1 Wednesday, October 12, 1881 Mrs. W.W. Mills, wife of the deputy U.S. Marshal, is among the latest acquisitions to El Paso society. A San Antonio theatrical troupe is speaking of a visit to El Paso. If they are first class let them come; they will make money. The music box at the Texas News Co.’s store is attracting much attention. It is a very fine in- strument and well worth listening to. Mrs. J. Calisher left on Monday’s train for a short stay at Hudson’s Hot Springs, N.M., where he goes to enjoy the benefit of the baths having suffered a great deal of late with rheumatism. Now that the plaza is being cleaned up, it would not be a bad idea to clear away John Woods’ old blacksmith shop and the stables connected with it.