Why London Never Became an Imperial Capital Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Admiralty Arch, Commissioned

RAFAEL SERRANO Beyond Indulgence THE MAN WHO BOUGHT THE ARCH commissioned We produced a video of how the building will look once restored and by Edward VII in why we would be better than the other bidders. We explained how Admiralty Arch, memory of his mother, Queen Victoria, and designed by Sir Aston the new hotel will look within London and how it would compete Webb, is an architectural feat and one of the most iconic buildings against other iconic hotels in the capital. in London. Finally, we presented our record of accountability and track record. It is the gateway between Buckingham Palace and Trafalgar Square, but few of those driving through the arch come to appreciate its We assembled a team that has sterling experience and track record: harmony and elegance for the simple reason that they see very little Blair Associates Architecture, who have several landmark hotels in of it. Londoners also take it for granted to the extent that they simply London to their credit and Sir Robert McAlpine, as well as lighting, drive through without giving it further thought. design and security experts. We demonstrated we are able to put a lot of effort in the restoration of public spaces, in conservation and This is all set to change within the next two years and the man who sustainability. has taken on the challenge is financier-turned-developer Rafael I have learned two things from my investment banking days: Serrano. 1. The importance of team work. When JP Morgan was first founded When the UK coalition government resolved to introduce more they attracted the best talent available. -

Never in the Field of Urban Geology Have So Many Granites Been Looked At

Urban Geology in London No. 22 Never in the field of urban geology have so many granites been looked at by so few! A stroll along the Victoria Embankment from Charing Cross to Westminster & Blackfriars Bridge Ruth Siddall & Di Clements This walk starts outside Charing Cross station and then turns down Villier’s Street to the Thames Embankment. The walker then must take a choice (or retrace their steps). One may either follow the Embankment east along the River Thames to Blackfriars Bridge, taking in Victoria Embankment Gardens and Cleopatra’s Needle on the way. Alternative, one may turn westwards towards Westminster and take in the RAF Memorial and the new Battle of Britain Memorial. A variety of London transport options can be picked up at the mainline and underground stations at either ends of the walk. The inspiration for this walk is a field trip that Di Clements led, on behalf of the Geologists’ Association, for the Department of Energy & Climate Change (DECC) on 18th September 2014 (Clements pers. comm.). Although the main focus of this walk is the embankment, we will also encounter a number of buildings and monument en route. As ever, information on architects and architecture is gleaned from Pevsner (Bradley & Pevsner, 1999; 2003) unless otherwise cited. By far and away, the main rock we will encounter on this walk is granite. Granite comes in many varieties, but always has the same basic composition, being composed of the major rock forming minerals, quartz, orthoclase and plagioclase feldspar and mica, either the variety muscovite or biotite or both. -

The London Gazette, Maech 22, 1901

THE LONDON GAZETTE, MAECH 22, 1901. 2041 Purchase, acquisition, laying out, planting and (e) Removal of certain gates, bars, or other improvement of parks, gardens, and open spaces. obstructions in streets. Fencing, drainage, buildings, entrance gates, (f) Expenditure in connection with historical bandstands, shelters, gymnasiums, boats, appli- buildings. ances, and conveniences of various kinds in Purchases of property, compensation, and parks and open spaces, formation and improve- works, rehousing of persons displaced, and other ment of lakes and ponds, and providing accommo- incidental expenditure under the London County dation for bathing, river-walls and embankments Council (Improvements) Act, 18P9. viz.:— and water supply. (a) Holborn to Strand, new street. Contributions towards purchase, acquisition, (b) Southampton-row widening. laying out and improvement of opeu spaces, (c) Wandsworth-road, Lambeth, widening. gardens and recreation grounds. (d) High-street, Kensington, widening. Purchase of propertj-, compensation, and (e) Cat and Mutton Bridge, Shoreditch, works in connection with the tunnel authorised reconstruction. by the Thames Tunnel (Blackwall) Acts, 1887 (f) OH Gravel-lane Bridge, St. George's-in- and 1888, including formation of approaches the-East, j econstruction. and provisions for rehousing persons displaced. Construction of railway sidings at Hortou Purchase of property, compensation, and con- including the exchange and purchase of lands, struction of subways, authorized by the Thames plant, and stock. Tunnel (Greenwich to Millwall) Act, 1897, and Purchase of land (the " Brickfield"), Lime- the Thames Tunnel (Rotherhithe and Ratcliff) house, for open space. Act, 1900. Purchases of property, compensation, and Schemes and contributions to schemes, acquisi- works, and other incidental expenditure under tion of lands, erection of dwellings, and other the London County Council (Improvements) Act, expenditure under the Housing of the Working 1900, viz. -

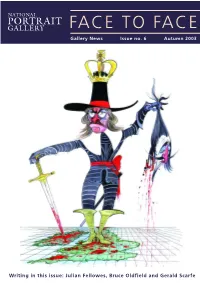

FACE to FACE Gallery News Issue No

P FACE TO FACE Gallery News Issue no. 6 Autumn 2003 Writing in this issue: Julian Fellowes, Bruce Oldfield and Gerald Scarfe FROM THE DIRECTOR The autumn exhibition Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits offers an unusual opportunity to see fascinating images of those who usually remain invisible. The exhibition offers intriguing stories of the particular individuals at the centre of great houses, colleges or business institutions and reveals the admiration and affection that caused the commissioning of a portrait or photograph. We are also celebrating the completion of the new scheme for Trafalgar Square with the young people’s education project and exhibition, Circling the Square, which features photographs that record the moments when the Square has acted as a touchstone in history – politicians, activists, philosophers and film stars have all been photographed in the Square. Photographic portraits also feature in the DJs display in the Bookshop Gallery, the Terry O’Neill display in the Balcony Gallery and the Schweppes Photographic Portrait Prize launched in November in the Porter Gallery. Gerald Scarfe’s rather particular view of the men and women selected for the Portrait Gallery is published at the end of September. Heroes & Villains, is a light hearted and occasionally outrageous view of those who have made history, from Elizabeth I and Oliver Cromwell to Delia Smith and George Best. The Gallery is very grateful for the support of all of its Patrons and Members – please do encourage others to become Members and enjoy an association with us, or consider becoming a Patron, giving significant extra help to the Gallery’s work and joining a special circle of supporters. -

The London Gazette, November 26, 1872

5702 THE LONDON GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 26, 1872, In Parliament.—Session 1873- ' 8. To amend and enlarge some of the powers Charing-cross and Victoria Embankment and provisions of (among other Acts) ".The Approach. Metropolis Management Act, 1855," " The (Power to Metropolitan Board of Works to Metropolis Management Amendment Act, 1856," Construct Street from Charing-cross to Vic- " The Metropolis Management Amendment Act, toria Embankment j Extension of Coal and 1862," "The Thames Embankment and Metro- Wine Duties; Borrowing of Money, and other polls Improvement (Loans) Act, 1864," "The Powers; Amendment of Acts.) Thames Embankment and Metropolis Improve- OTICE is hereby given that the Metro- ment (Loans) Act, 1868," "The Metropolitan N politan Board of Works (who are in this Board of Works (Loans) Acts, 1869 to 1871," nqtice referred to as "the Board") intend to and of the several London Coal and Wine Duties apply to Parliament in the ensuing Session for Continuance Acts. leave to bring in a Bill to confer upon them the 9. To incorporate with the Bill the necessary following or some of the following among other provisions of " The Lands Clauses Consolidation powers (that is to say) :— Acts, 1845, 1860, and 1869," to vary and extin- 1. To make wholly in the parish of St. guish all rights and privileges which would inter- Martin-in-the-Fields, in the county of Middlesex, fere with the objects of the Bill, and to confer a new street to commence at Charing-cross at or upon the Board all such other rights, powers, and near Northumberland House, passing through privileges as may be necessary or expedient in that house and the premises connected therewith, carrying out the objects of the Bill. -

The London Gazette, November 24, 1865. 5843

THE LONDON GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 24, 1865. 5843 :; s. .from -Duke-street to Saint James's-park with M. A widening and improvement of Millbank- access for foot passengers from Charles-street street on the western side thereof, from Great /• -.to Saint James.;8-park ; College-street to Wood-street; ,7 .B.:.A;new street, from Charles-street to Great N. A widening and improvement of Great -: _ George-street, commencing two hundred and College-stret on the southern side thereof^ : -ninety feet, or thereabouts, eastwards from from Little College-street to Abingdon-street the centre of Duke*street. measured along and the acquisition of all the property; Charles-street, and terminating two hundred bounded northwardly by Great College- and seventy feet or. thereabouts from the street, southwardly by Woodrstreet, east-: .: , centre of Delahay-street, measured, in* an ward by Millbank-street, and westwardiy by .easterly direction along Great George-street, Little College-street; ; .. j all in the parish of Saint Margaret, Westr 0. An embankment on the left bank of the . •. minster ; • River Thames, .in the parishes of Saint E...A new street, from Parliament-street to Margaret and Saint John the Evangelist^ Duke-street, commencing by a junction with . Westminster, or one of them, being a con- : . Parliament-street at a point two hundred tinuation in a southerly direction of the * . feet, or thereabouts, measured in a northerly present embankment, in connection with.the direction along Parliament-street from the Houses of Parliament for a distance of five" . south-western corner thereof; and terminat- hundred fuet or thereabouts, measured along :- ing in Duke-street at a point one. -

State Opening of Parliament State Opening of Parliament 1

State Opening of Parliament State Opening of Parliament 1 The State Opening of Parliament marks the Start of Parliament’s year start of the parliamentary year and the Queen’s The Queen’s Speech, delivered at State Opening, is the public Speech sets out the government’s agenda. statement of the government’s legislative programme for Parliament’s next working year. State Opening is the only regular occasion when the three constituent parts of Parliament that have to give their assent to new laws – the Sovereign, the House of Lords and the House of Commons – meet. The Speech is written by the government and read out in the House of Lords. Parliamentary year Queen’s Speech A ‘parliament’ runs from one general Members of both Houses and guests election to the next (five years). It is including judges, ambassadors and high broken up into sessions which run for commissioners gather in the Lords about a year – the ‘parliamentary year’. chamber for the speech. Many wear national or ceremonial dress.The Lord State Opening takes place on the first Chancellor gives the speech to the day of a new session. The Queen’s Queen who reads it out from the Speech marks the formal start to the Throne (right and see diagram on year. Neither House can conduct any page 4). business until after it has been read. Setting the agenda The speech is central to the State Contents Opening ceremony because it sets out the government’s legislative agenda Start of Parliament’s year 1 for the year. The final words, ‘Other Buckingham Palace to the House of Lords 2 measures will be laid before you’, give How it happens 4 the government flexibility to introduce Back to work 5 other bills (draft laws). -

Victoria Embankment Foreshore Hoarding Commission

Victoria Embankment Foreshore Hoarding Commission 1 Introduction ‘The Thames Wunderkammer: Tales from Victoria Embankment in Two Parts’, 2017, by Simon Roberts, commissioned by Tideway This is a temporary commission located on the Thames Tideway Tunnel construction site hoardings at Victoria Embankment, 2017-19. Responding to the rich heritage of the Victoria Embankment, Simon Roberts has created a metaphorical ‘cabinet of curiosities’ along two 25- metre foreshore hoardings. Roberts describes his approach as an ‘aesthetic excavation of the area’, creating an artwork that reflects the literal and metaphorical layering of the landscape, in which objects from the past and present are juxtaposed to evoke new meanings. Monumental statues are placed alongside items that are more ordinary; diverse elements, both man-made and natural, co-exist in new ways. All these components symbolise the landscape’s complex history, culture, geology, and development. Credits Artist: Simon Roberts Images: details from ‘The Thames Wunderkammer: Tales from Victoria Embankment in Two Parts’ © Simon Roberts, 2017. Archival images: © Copyright Museum of London; Courtesy the Trustees of the British Museum; Wellcome Library, London; © Imperial War Museums (COM 548); Courtesy the Parliamentary Archives, London. Special thanks due to Luke Brown, Demian Gozzelino (Simon Roberts Studio); staff at the Museum of London, British Museum, Houses of Parliament, Parliamentary Archives, Parliamentary Art Collection, Wellcome Trust, and Thames21; and Flowers Gallery London. 1 About the Artist Simon Roberts (b.1974) is a British photographic artist whose work deals with our relationship to landscape and notions of identity and belonging. He predominantly takes large format photographs with great technical precision, frequently from elevated positions. -

Secret Side of London Scavenger Hunt

Secret Side of London Scavenger Hunt What better way to celebrate The Senior Section Spectacular than by exploring one of the greatest cities in the world! London is full of interesting places, monuments and fascinating museums, many of which are undiscovered by visitors to our capital city. This scavenger hunt is all about exploring a side to London you might never have seen before… (all these places are free to visit!) There are 100 Quests - how many can you complete and how many points can you earn? You will need to plan your own route – it will not be possible to complete all the challenges set in one day, but the idea is to choose parts of London you want to explore and complete as many quests as possible. Read through the whole resource before starting out, as there are many quests to choose from and bonus points to earn… Have a great day! The Secret Side of London Scavenger Hunt resource was put together by a team of Senior Section leaders in Hampshire North to celebrate The Senior Section Spectacular in 2016. As a county, we used this resource as part of a centenary event with teams of Senior Section from across the county all taking part on the same day. We hope this resource might inspire other similar events or maybe just as a way to explore London on a unit day trip…its up to you! If you would like a badge to mark taking part in this challenge, you can order a Hampshire North County badge designed by members of The Senior Section to celebrate the centenary (see photo below). -

In and Around Buckingham Palace

MY BABA’s In and Around BuckinghamBy Nanny Anita Palace There are so many wonderful things to do in St. James’s Directions: and Green Park that are not included in this trail, so feel free to use this a base in which This trail starts on Buckingham you can go off and explore the Palace Road by the Royal Mews surrounding area. and finishes at the other end of The Mall by Admiralty Arch. • Start at the Royal Mews located on Buckingham Palace Road; if you do go in for a visit then you will exit further along Buckingham Palace Road. Either way, continue down the road until you come to Buckingham Palace. • Head into St. James’s Park and follow The Mall down to Admiralty Arch. • Walking down The Mall there are St. James’s Palace and The Mall Galleries on your left. • Towards the end of the Mall, on the right, is The Household Cavalry Museum. If you are planning to be there in time to see the changing of the guards, be aware that it will become extremely busy and the whole process takes around 45 minutes. For more fun things to do visit the My Baba blog at www.mybaba.com or tweet your trail @ mybabatweets INFORMATION For Attractions ATTRACTION OPENING TIMES COST February, March, November Adult 8.75 Royal Mews 10am-4pm Under 17s 5.40 April-October Under 5s free 10am-5pm Open during the sum- Adult 19.75 mer only: check their Buckingham Under 17s 11.25 website for details. Palace Under 5s free Adults 3.00 Daily 10am-5pm Mall Galleries Under 18s free April-October Adults 7.00 10am-6pm Household Calvary Child 5.00 November-March Museum Under 5s free 10am-5pm N.B Security into these attractions is very tight and you will be subject to airport style checks. -

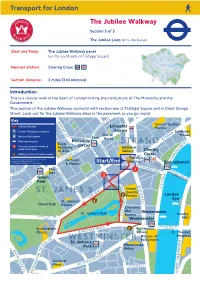

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park. -

London and Its Main Drainage, 1847-1865: a Study of One Aspect of the Public Health Movement in Victorian England

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 6-1-1971 London and its main drainage, 1847-1865: A study of one aspect of the public health movement in Victorian England Lester J. Palmquist University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Palmquist, Lester J., "London and its main drainage, 1847-1865: A study of one aspect of the public health movement in Victorian England" (1971). Student Work. 395. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/395 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LONDON .ML' ITS MAIN DRAINAGE, 1847-1865: A STUDY OF ONE ASPECT OP TEE PUBLIC HEALTH MOVEMENT IN VICTORIAN ENGLAND A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska at Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Lester J. Palmquist June 1971 UMI Number: EP73033 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI EP73033 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC.