New Avian Records Along the Elevational Gradient of Mt. Wilhelm, Papua New Guinea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papua New Guinea Huon Peninsula Extension 26Th June to 1St July 2018 (6 Days) Trip Report

Papua New Guinea Huon Peninsula Extension 26th June to 1st July 2018 (6 days) Trip Report Pesquet’s Parrots by Sue Wright Tour Leader: Adam Walleyn Rockjumper Birding Tours View more tours to Papua New Guinea Trip Report – RBL Papua New Guinea - Huon Peninsula Extension I 2018 2 Tour Summary This was our inaugural Huon Peninsula Extension. Most of the group started out with a quick flight from Moresby into Nadzab Airport. Upon arrival, we drove to our comfortable hotel on the outskirts of Lae City. After getting settled in, we set off on a short but very productive bird walk around the hotel’s expansive grounds. The best thing about the walk was how confiding the birds were –they are clearly not hunted much around here! Red-cheeked Parrot, Coconut Lorikeet, Orange-bellied Fruit Dove, Torresian Imperial Pigeon, White-bellied Cuckooshrike, Yellow-faced Myna, and Singing Starling all vied for our attention right in the parking lot. As we took a short wander, we added Hooded Butcherbird, New Guinea Friarbird and look-alike Brown Oriole, and Black and Olive-backed Sunbirds to our growing tally. A Buff-faced Pygmy Parrot zipped overhead providing just a quick view, but the highlight of the walk was clearly the Palm Cockatoo that sat out feeding contentedly on fruits – admittedly a bit of a surprise to find this species so close to a major urban centre! We were relieved when Sue had arrived and Pinon’s Imperial Pigeon by Markus Lilje joined us for dinner to complete the group! The real adventure began early the next morning, with a drive back to the airport where we were to board our flight into the Huon. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

The Avifauna of Mt. Karimui, Chimbu Province, Papua New Guinea, Including Evidence for Long-Term Population Dynamics in Undisturbed Tropical Forest

Ben Freeman & Alexandra M. Class Freeman 30 Bull. B.O.C. 2014 134(1) The avifauna of Mt. Karimui, Chimbu Province, Papua New Guinea, including evidence for long-term population dynamics in undisturbed tropical forest Ben Freeman & Alexandra M. Class Freeman Received 27 July 2013 Summary.—We conducted ornithological feld work on Mt. Karimui and in the surrounding lowlands in 2011–12, a site frst surveyed for birds by J. Diamond in 1965. We report range extensions, elevational records and notes on poorly known species observed during our work. We also present a list with elevational distributions for the 271 species recorded in the Karimui region. Finally, we detail possible changes in species abundance and distribution that have occurred between Diamond’s feld work and our own. Most prominently, we suggest that Bicolored Mouse-warbler Crateroscelis nigrorufa might recently have colonised Mt. Karimui’s north-western ridge, a rare example of distributional change in an avian population inhabiting intact tropical forests. The island of New Guinea harbours a diverse, largely endemic avifauna (Beehler et al. 1986). However, ornithological studies are hampered by difculties of access, safety and cost. Consequently, many of its endemic birds remain poorly known, and feld workers continue to describe new taxa (Prat 2000, Beehler et al. 2007), report large range extensions (Freeman et al. 2013) and elucidate natural history (Dumbacher et al. 1992). Of necessity, avifaunal studies are usually based on short-term feld work. As a result, population dynamics are poorly known and limited to comparisons of diferent surveys or diferences noticeable over short timescales (Diamond 1971, Mack & Wright 1996). -

Papua New Guinea Huon Peninsula Extension I 25Th to 30Th June 2019 (6 Days) Trip Report

Papua New Guinea Huon Peninsula Extension I 25th to 30th June 2019 (6 days) Trip Report Huon Astrapia by Holger Teichmann Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Adam Walleyn Rockjumper Birding Tours www.rockjumperbirding.com Trip Report – RBL Papua New Guinea Huon Extension I 2019 2 Tour in Detail Our group met up in Port Moresby for the late morning flight to Lae’s Nadzab airport. Upon arrival, we transferred to our comfortable hotel on the outskirts of Lae city. A walk around the expansive grounds turned up some 23 species to get our lists well underway, including Orange-bellied and Pink-spotted Fruit Dove (the latter of the distinct and range-restricted plumbeicollis race), Torresian Imperial Pigeon, Eclectus Parrot, and Yellow-faced Myna, not to mention perhaps 1,000 Spectacled Flying Foxes creating quite the sight and sound! Early the next morning we were back at Nadzab airport, where a quick scan of the airfield produced some Horsfield’s Bush Larks and also excellent looks at a male Papuan Harrier that did a close flyby being bombarded by numerous Masked Lapwings! We were soon boarding our charter flight Pink-spotted Fruit Doves by Holger Teichmann over the rugged Huon mountains, although we quickly entered dense clouds and could see nothing of these impressive mountains. After some half an hour of flying through thick cloud on the plane’s GPS track, we suddenly descended and made an uphill landing at Kabwum airstrip! Our land cruiser was there, waiting for us, and after loading bags and ourselves onboard we made the bumpy drive up many switchbacks to reach the high ridge above Kabwum. -

Sericornis, Acanthizidae)

GENETIC AND MORPHOLOGICAL DIFFERENTIATION AND PHYLOGENY IN THE AUSTRALO-PAPUAN SCRUBWRENS (SERICORNIS, ACANTHIZIDAE) LESLIE CHRISTIDIS,1'2 RICHARD $CHODDE,l AND PETER R. BAVERSTOCK 3 •Divisionof Wildlifeand Ecology, CSIRO, P.O. Box84, Lyneham,Australian Capital Territory 2605, Australia, 2Departmentof EvolutionaryBiology, Research School of BiologicalSciences, AustralianNational University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601, Australia, and 3EvolutionaryBiology Unit, SouthAustralian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia ASS•CRACr.--Theinterrelationships of 13 of the 14 speciescurrently recognized in the Australo-Papuan oscinine scrubwrens, Sericornis,were assessedby protein electrophoresis, screening44 presumptivelo.ci. Consensus among analysesindicated that Sericorniscomprises two primary lineagesof hithertounassociated species: S. beccarii with S.magnirostris, S.nouhuysi and the S. perspicillatusgroup; and S. papuensisand S. keriwith S. spiloderaand the S. frontalis group. Both lineages are shared by Australia and New Guinea. Patternsof latitudinal and altitudinal allopatry and sequencesof introgressiveintergradation are concordantwith these groupings,but many featuresof external morphologyare not. Apparent homologiesin face, wing and tail markings, used formerly as the principal criteria for grouping species,are particularly at variance and are interpreted either as coinherited ancestraltraits or homo- plasies. Distribution patternssuggest that both primary lineageswere first split vicariantly between -

Bob Ake with Logistics Arranged by the Papua Bird Club ( Founded by Kris Tindige and His Wife Shita (Maria)

WEST PAPUA August 2008 This trip was organized by Bob Ake with logistics arranged by the Papua Bird Club (www.papuabirdclub.com), founded by Kris Tindige and his wife Shita (Maria). Kris, who had also served as the major bird guide for trips to this area, died one year ago. Shita ably took care of all the very complicated arrangements and with the help of Untu, a childhood friend of Kris, managed to guide us during the trip. In such a difficult country as Indonesia it is extremely important to have someone that knows exactly how to handle local tribes as well as military officers and the other people who grant the all-important permits. Shita’s former occupation as a lawyer and her background in West Papua allowed her to smooth the way, solving most problems before they occurred. The logistics were handled without incident. We were guided to locations for most of the trophy birds, but we missed some of the skulkers and harder-to-get birds. The use of tape playback would have improved this aspect. Local guides were used in the Arfaks (Zeth Wongger) and at Nimbokrang (Jamil) which was a plus, although lack of spoken English slowed our getting onto the birds during the trip. A good laser pointer would improve the communication. That said, we can certainly recommend Papua Bird Club as an organizer for any tour in West Papua, Sulawesi, and Halmahera, not only for the professionalism and very reasonable prices, but also for their intentions. Shita’s and Untu’s determination to do whatever possible to save the remaining forests and birds in West Papua is reason enough, but adding to this their strong involvement in helping the local people with food, education and knowledge about nature makes supporting them compelling. -

Ultimate Papua New Guinea Ii

The fantastic Forest Bittern showed memorably well at Varirata during this tour! (JM) ULTIMATE PAPUA NEW GUINEA II 25 AUGUST – 11 / 15 SEPTEMBER 2019 LEADER: JULIEN MAZENAUER Our second Ultimate Papua New Guinea tour in 2019, including New Britain, was an immense success and provided us with fantastic sightings throughout. A total of 19 Birds-of-paradise (BoPs), one of the most striking and extraordinairy bird families in the world, were seen. The most amazing one must have been the male Blue BoP, admired through the scope near Kumul lodge. A few females were seen previously at Rondon Ridge, but this male was just too much. Several males King-of-Saxony BoP – seen displaying – ranked high in our most memorable moments of the tour, especially walk-away views of a male obtained at Rondon Ridge. Along the Ketu River, we were able to observe the full display and mating of another cosmis species, Twelve-wired BoP. Despite the closing of Ambua, we obtained good views of a calling male Black Sicklebill, sighted along a new road close to Tabubil. Brown Sicklebill males were seen even better and for as long as we wanted, uttering their machine-gun like calls through the forest. The adult male Stephanie’s Astrapia at Rondon Ridge will never be forgotten, showing his incredible glossy green head colours. At Kumul, Ribbon-tailed Astrapia, one of the most striking BoP, amazed us down to a few meters thanks to a feeder especially created for birdwatchers. Additionally, great views of the small and incredible King BoP delighted us near Kiunga, as well as males Magnificent BoPs below Kumul. -

Download Full Text (Pdf)

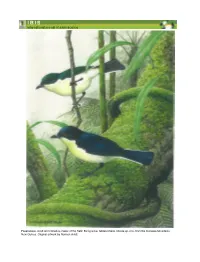

FRONTISPIECE. Adult and immature males of the Satin Berrypecker Melanocharis citreola sp. nov. from the Kumawa Mountains, New Guinea. Original artwork by Norman Arlott. Ibis (2021) doi: 10.1111/ibi.12981 A new, undescribed species of Melanocharis berrypecker from western New Guinea and the evolutionary history of the family Melanocharitidae BORJA MILA, *1 JADE BRUXAUX,2,3 GUILLERMO FRIIS,1 KATERINA SAM,4,5 HIDAYAT ASHARI6 & CHRISTOPHE THEBAUD 2 1National Museum of Natural Sciences, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), Madrid, 28006, Spain 2Laboratoire Evolution et Diversite Biologique, UMR 5174 CNRS-IRD, Universite Paul Sabatier, Toulouse, France 3Department of Ecology and Environmental Science, UPSC, Umea University, Umea, Sweden 4Biology Centre of Czech Academy of Sciences, Institute of Entomology, Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic 5Faculty of Sciences, University of South Bohemia, Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic 6Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), Cibinong, Indonesia Western New Guinea remains one of the last biologically underexplored regions of the world, and much remains to be learned regarding the diversity and evolutionary history of its fauna and flora. During a recent ornithological expedition to the Kumawa Moun- tains in West Papua, we encountered an undescribed species of Melanocharis berrypecker (Melanocharitidae) in cloud forest at an elevation of 1200 m asl. Its main characteristics are iridescent blue-black upperparts, satin-white underparts washed lemon yellow, and white outer edges to the external rectrices. Initially thought to represent a close relative of the Mid-mountain Berrypecker Melanocharis longicauda based on elevation and plu- mage colour traits, a complete phylogenetic analysis of the genus based on full mitogen- omes and genome-wide nuclear data revealed that the new species, which we name Satin Berrypecker Melanocharis citreola sp. -

![6(9): 72. Note: [Fife Bay]. 2. Baak, Connie;](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1352/6-9-72-note-fife-bay-2-baak-connie-1721352.webp)

6(9): 72. Note: [Fife Bay]. 2. Baak, Connie;

1 Bibliography 1. B., Jane. The First Crocodile. The Papuan villager. 1934; 6(9): 72. Note: [Fife Bay]. 2. Baak, Connie; Bakker, Mary; Meij, Dick van der, Editors. Tales from a Concave World: Liber Amicorum Bert Voorhoeve. Leiden: Leiden University, Department of Languages and Cultures of South-East Asia and Oceania, Projects Division; 1995. xx, 601 pp. 3. Baal, J. van. Algemene sociaal-culturele beschouwingen. In: Klein, Ir W. C., Editor. Nieuw Guinea: de ontwikkeling op economisch, sociaal een cultureel gebied, in Nederlands en Australisch Nieuw Guinea. 's-Gravenhage: Staatsdrukkerij- en uitgeverijbedrijf; 1953; I: 230-258. Note: [admin: general NG]. 4. Baal, J. van. The Cult of the Bullroarer in Australia and Southern New Guinea. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 1963; 119: 201-214 + Plates I-II. Note: [admin: Marind-anim; from lit: Kiwai, Keraki, Orokolo]. 5. Baal, J. van. De bevolking van Zuid-Nieuw-Guinea onder Nederlandsch Bestuur: 36 Jaren. Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 1939; 79: 309-414 + 3 Foldout Tables + Foldout Map. Note: [admin: Marind]. 6. Baal, J. van. De bevolking van Zuid-Nieuw-Guinea: De Papoea's van Zuid-Nieuw-Guinea onder Europeesch Bestuur. Tijdschrift "Nieuw-Guinea". 1941; 5-6: 174-192 + Foldout Map, 193-216; 48-68, 71-94. Note: [admin: south coast IJ]. 7. Baal, J. van. De mythe als geschiedbron: Een kanttekening bij Dr. Kamma's "Spontane acculturatie op Nieuw-Guinea". De Heerbaan. 1961; 14: 129-130. Note: [admin: Biak]. 8. Baal, J. van. Dema: Description and Analysis of Marind-anim Culture (South New Guinea). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff; 1966. -

Biodiversity Assessment of the PNG LNG Upstream Project Area, Southern Highlands and Hela Provinces, Papua New Guinea

Biodiversity assessment of the PNG LNG Upstream Project Area, Southern Highlands and Hela Provinces, Papua New Guinea Edited by Stephen Richards ISBN: 978-0-646-98050-8 (PDF version) Suggested citation: Richards, S.J. (Editor) 2017. Biodiversity Assessment of the PNG LNG Upstream Project Area, Southern Highlands and Hela Provinces, Papua New Guinea. ExxonMobil PNG Limited. Port Moresby. © 2017 ExxonMobil PNG Cover image: Formerly considered a bird-of-paradise, the Crested Satinbird (Cnemophilus macgregorii) is now known to belong to a small family of birds that occurs only in New Guinea’s central cordillera. Not previously reported from the PNG LNG Project Area, an isolated population of this restricted range species was found in the higher elevation forests at the western end of Hides Ridge. This bird was banded and released as part of the bird survey. PNG LNG is operated by a subsidiary of ExxonMobil in co-venture with: Biodiversity Assessment of the PNG LNG Upstream Project Area, Southern Highlands and Hela Provinces, Papua New Guinea Stephen Richards (Editor) TABLE OF CONTENTS Participants ...........................................................................................................................................................................................i Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................................................i Acronyms and Abbreviations ...........................................................................................................................................................ii -

Papua New Guinea 2015

Field Guides Tour Report Papua New Guinea 2015 Jun 28, 2015 to Jul 16, 2015 Jay VanderGaast For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. There's nothing like a bright red parrot to brighten up a bush! This Papuan Lorikeet (which the field guide splits as Stella's Lorikeet) made multiple visits to a Schefflera plant just off the Kumul Lodge balcony. Photo by participant Greg Griffith. This year's was one of the most unusual Niugini trips I've had, in a way that I don't expect to be repeated anytime soon: for the first time ever, we didn't once have to bird in the rain! In fact, we had pretty clear and sunny conditions through most of the tour, with even perpetually foggy, misty Tabubil providing blue skies and sunshine for most of our stay there. As a result, we had some of the best viewing conditions I've ever experienced on this tour, even if some bird activity was suppressed by the gorgeous weather. Add in the fact that the local airlines performed well, and this was a pretty darned good run of this often challenging trip. Despite the good weather, the total number of species we saw was remarkably similar to the total we find in years with more typical weather. But even if it didn't increase the bird list, it sure did make for more pleasant birding conditions, and resulted in some fine views of several birds that have been troublesome in the past. -

Download PNG Adventurous Training Guide by Reg Yates

The PNG Adventurous Training Guide 2017 By Reg Yates RFD [email protected] Melbourne, February 2017 “Time spent on reconnaissance is seldom wasted” “Planning & Preparation Prevents Poor Performance” This Guide provides outline military or colonial history notes on the following, 8 day - 10 day activities; it does not contain sketch maps, photos or images; readers should consult the various books listed (though some are out of print, or very expensive) and the survey maps suggested; there is no index. Subject to Reg Yates‟ copyright as author this Guide may be circulated free to anyone wanting to read and learn more about Australians in Papua & New Guinea since the First World War. Bougainville; including Porton Plantation, Slater‟s Knoll, Torokina and Panguna‟s abandoned mine. Shaggy Ridge; including Nadzab, Lae War Cemetery and Kaiapit. Huon Peninsula including Finschafen, Scarlet Beach and Sattelberg; “Fear Drive My Feet” by the late Peter Ryan, MM, MID; Mt Saruwaged and Kitamoto‟s IJA escape route; Wau-Salamaua including the Black Cat and Skin Diwai tracks; Bulldog-Wau Army Road and the Bulldog Track; Rabaul- Bita Paka and AE-1; Lark Force and Tol Plantation; the IJA underground hospital Mt Wilhelm; with local guides Walindi Plantation, as a base for battlefield survey tours to Cape Gloucester, Willaumez Peninsula and Awul/Uvol; reconnaissance for caving in the Nakanai mountains; and scuba-diving and snorkelling; Sepik River; Houna Mission to Angoram paddling a dugout canoe; Wewak and Dagua by 4WD; White-water rafting on the Watut River; Mt Victoria trek; Karius & Champion‟s 1926-1928 crossing of the Fly River-Sepik River headwaters; Hindenburg Range.