This Chapter Explores Competitive Street Dance Crew Choreography in Relation to Interdisciplinary Theoretical Frameworks Regarding Virtuosity and Excess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8550/list-of-animated-films-and-matched-comparisons-posted-as-supplied-by-author-8550.webp)

List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]

Appendix : List of animated films and matched comparisons [posted as supplied by author] Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date Snow White and the G 1937 Saratoga ‘Passed’ Stella Dallas G Seven Dwarfs Pinocchio G 1940 The Great Dictator G The Grapes of Wrath unrated Bambi G 1942 Mrs. Miniver G Yankee Doodle Dandy G Cinderella G 1950 Sunset Blvd. unrated All About Eve PG Peter Pan G 1953 The Robe unrated From Here to Eternity PG Lady and the Tramp G 1955 Mister Roberts unrated Rebel Without a Cause PG-13 Sleeping Beauty G 1959 Imitation of Life unrated Suddenly Last Summer unrated 101 Dalmatians G 1961 West Side Story unrated King of Kings PG-13 The Jungle Book G 1967 The Graduate G Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner unrated The Little Mermaid G 1989 Driving Miss Daisy PG Parenthood PG-13 Beauty and the Beast G 1991 Fried Green Tomatoes PG-13 Sleeping with the Enemy R Aladdin G 1992 The Bodyguard R A Few Good Men R The Lion King G 1994 Forrest Gump PG-13 Pulp Fiction R Pocahontas G 1995 While You Were PG Bridges of Madison County PG-13 Sleeping The Hunchback of Notre G 1996 Jerry Maguire R A Time to Kill R Dame Hercules G 1997 Titanic PG-13 As Good as it Gets PG-13 Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date A Bug’s Life G 1998 Patch Adams PG-13 The Truman Show PG Mulan G 1998 You’ve Got Mail PG Shakespeare in Love R The Prince of Egypt PG 1998 Stepmom PG-13 City of Angels PG-13 Tarzan G 1999 The Sixth Sense PG-13 The Green Mile R Dinosaur PG 2000 What Lies Beneath PG-13 Erin Brockovich R Monsters, -

Dondraico Johnson Resume

Dondraico Johnson choreographer selected credits contact: (818) 509-0121 FILM The Conjuring 3 (September 2020) Choreographer Dir. Michael Chaves /Warner Bros. Pictures Ghostbusters Choreographer Dir. Paul Feig /Sony Dirty Grandpa Choreographer Dir. Dan Mazer /Lionsgate Step Up 5 Choreographer Dir. Trish Sie /Summit The Infamous Choreographer Dir. Anthony Hemmingway Mike and Dave Need Wedding Dates Asst. Choreographer Dir. Jake Szymanski The Ridiculous Six Asst. Choreographer Dir. Frank Coraci /Netflix Jack & Jill Asst. Choreographer Columbia /Dir. Dennis Dugan /Chor. Jamal Sims Footloose Asst. Choreographer Dir. Craig Brewer /Chor. Jamal Sims Big Mommas: Like Father, Like Son Asst. Choreographer Dir. John Whitesell /Chor. Jamal Sims Michael Jackson’s This Is It Asst. Choreographer Dir. Kenny Oretega /Sony Pictures TELEVISION 2019 BET Awards – Lil Nas X Co-Choreographer BET Raven’s Home Choreographer Disney Channel E! Funny Dance Show Choreographer E! TALES Choreographer Dir. Erica Watson Unsolved Choreographer Universal Cable Productions American Crime Story: Versace Choreographer 20th Century Fox TV American Crime Story: The People v. OJ Choreographer 20th Century Fox TV Underground Choreographer Dir. Anthony Hemmingway RuPaul’s Drag Race (Season 7) Choreographer World of Wonder Forte Forte Forte Assoc. Choreographer Ballandi Multimedia Disney Parks Christmas Day 2010 - Sean Kingston Choreographer ABC /Harborlight Entertainment Disney Parks Christmas Day 2009 - The Jonas Brothers Choreographer ABC /Harborlight Entertainment 2010 Teen Choice Awards - Cast of Step Up 3D Asst. Choreographer FOX /Chor. Jamal Sims Jimmy Fallon w/Cast of Step Up 3D Asst. Choreographer NBC /Chor. Jamal Sims 2010 Much Music Video Awards - Miley Cyrus Choreographer CTV Global Media Univision Miami - Cast of Step Up 3D Asst. -

Mia Michaels Concerts/Tours/Events

Mia Michaels Concerts/Tours/Events: Celine Dion "A New Day" / Choreographer Caesars' Palace / Las Vegas Caesars' Palace Las Vegas / 2002-2007 Celine Dion "Taking Chances" Choreographer World Tour / 2005 Cirque De Soleil "Delirium" Choreographer So You Think You Can Dance Contributing Choreographer Tour Madonna "Drowned" World Contributing Choreographer Tour / 2001 Anna Vissi Greek Superstar Director / Choreographer Live Shows in Athens / 2004- 2008 Prince Promotional Tour / Choreographer 2001 Eurovision Angelica / 2005 Director / Choreographer Mia Michaels Raw New York Founder, Director and City Choreographer Les Ballet Jazz De Montreal / Commissioned Original Work Commissioned Original Work Giordano Jazz Dance Chicago Commissioned Original Work / Commissioned Original Work Oslo Dance International / Commissioned Original Work Commissioned Original Work Joffrey Ballet 2 New York City Guest Choreographer International Dance Festival Guest Choreographer Amsterdam Kirov Academy Washington Guest Choreographer DC Jazz Theater of Amsterdam / Commissioned Original Work Commissioned Original Work Miami Movement Dance Founder, Director, and Company Choreographer Harvard Keynote Speaker Harvard in Arts Reflection Program (HARP) Teaching: Joffrey Ballet School Artistic Director| Jazz & Contemporary Theatre: NY Spectacular / Radio City Choreographer Music Hall starring The Rockettes Finding Neverland Choreographer Lunt-Fontaine Theater / 2015 Hello Dolly! w/ Tovah Choreographer Papermill Playhouse / 2005 Feldshuh West Side Story Choreographer Arkansas -

Vinh Bui Sag-Core

VINH BUI SAG-CORE Television Country Music Awards 2019 DJ/Dancer Dick Clark "Carrie Underwood" Productions/CBS Fake Off season 2 Dancer/ Director Tru TV Glee Dancer Nick Woodlee So You Think You Can Dance Dancer Mixd Elements America's Best Dance Crew Mix'd Elements Dancer MTV Season 7 Queen Latifah Show Dancer iLuminate Teen Nick Halo Awards iLuminate Dancer Kevin Wilson Contact Victoria Secret Fashion Show Spice Girls Back Up CBS The Movement Talent Dancer Agency (323) 462-5300 America's Got Talent Dancer Mix'd Elements Simon Cowell Attributes Guasup?! Spanish TV Madrid iLuminate Dancer Miral Height 5'5" All That Skate 2010 Champions Breakdancer NBC Weight 130 lbs ITQ Japanese TV SHOW iLuminate Dancer Miral Gender Male Spice Girls "Children In Need" Spice Girls Back Up BBC Hair Black Dancer Hair Length Short A.S.A.P. Dancer TFC Channel Eyes Brown MR Philippines Contributing TFC Channel Choreographer Sizes Coat 36 Film Coat Length REGULAR Spice Girls Reunion World Tour Dancer Documentary Sleeve 32 Commercial Waist 30 BMW Featured Background Litza Bixler Inseam 30 Dancer Shoe 7.5 Cisco "Sparks" DJ Dir: Neck 15.5 Fiat 500x 2016 DJ Dir: Ken Alridge Mountain Dew Dancer Dir: Paul Powers Skol Beer "Viva Las Vegas" Principal Dancer Delirio Films Sprite "Face Off" Principal DJ Rob Pritts Disney XD Promo "Kickin It" Principal Stunt Ninja Jeremey Fels LG "Tracfone" Principal DJ Filip Tellander B- Reel Films Mc Donalds "Karaoke" Principal Dancer Don Rase Bully Pictures Beeline Vietnam Lead MC rapper Tony Petrossian Telecom"Malibu" RockHard Charter -

SUMMIT ENTERTAINMENT in Associazione Con OFFSPRING ENTERTAINMENT

Medusa Film presenta una produzione SUMMIT ENTERTAINMENT in associazione con OFFSPRING ENTERTAINMENT STEP UP Channing Tatum, Jenna Dewan Mario, Drew Sidora e Rachel Griffiths un film di ANNE FLETCHER prodotto da Patrick Wachsberger, Erik Feig, Adam Shankman, Jennifer Gibgot distribuzione www.medusa.it IL CAST Tyler Gage CHUNNING TATUM Nora Clark JENNA DEWAN Mac Carter DAMAINE RADCLIFF Skinny Carter DE’SHAWN WASHINGTON Miles Darby MARIO Lucy Avila DREW SIDORA Direttrice Gordon RACHEL GRIFFITHS Brett Dolan JOSH HENDERSEN Andrew TIM LACATENA Camille ALYSON STONER Omar HEAVY D Mamma di Nora/Katherine Clark DEIRDRE LOVEJOY 2 I REALIZZATORI Regia ANNE FLETCHER Sceneggiatura DUANE ADLER MELISSA ROSENBERG Produttori PATRICK WACHSBERGER ERIK FEIG ADAM SHANKMAN JENNIFER GIBGOT Produttori esecutivi BOB HAYWARD DAVID GARRETT JOHN H. STARKE Direttore della fotografia MICHAEL SERESIN Scenografo SHEPHERD FRANKEL Montaggio NANCY RICHARDSON Costumi ALIX HESTER Compositore AARON ZIGMAN Supervisore alle musiche BUCK DAMON Uscita 26 gennaio 2007 Nazionalità U.S.A. Durata 100 minuti 3 SINOSSI Lui è un ribelle spavaldo proveniente dalla parte degradata di Baltimora; lei una ballerina privilegiata di una scuola d’elite di arti dello spettacolo. I loro mondi non potrebbero essere più diversi ma quando i loro destini entrano in collisione, tra di loro volano scintille che accendono una favola esilarante alimentata dall’ hip- hop facendo realizzare un sogno improbabile grazie all’unica chance esistente. Con un interessante cast di giovani nuovi talenti del grande schermo, STEP UP è una storia realistica di trascendenza guidata da musica e danza. Tyler Gage (CHANNING TATUM) è cresciuto trascorrendo la propria vita sulle strade dure della città e sa che è improbabile che ce la possa mai fare ad andarsene. -

February 12 – 16, 2016

February 12 – 16, 2016 danceFilms.org | Filmlinc.org ta b l e o F CONTENTS DA N C E O N CAMERA F E S T I VA L Inaugurated in 1971, and co-presented with Dance Films Association and the Film Society of Lincoln Center since 1996 (now celebrating the 20th anniversary of this esteemed partnership), the annual festival is the most anticipated and widely attended dance film event in New York City. Each year artists, filmmakers and hundreds of film lovers come together to experience the latest in groundbreaking, thought-provoking, and mesmerizing cinema. This year’s festival celebrates everything from ballet and contemporary dance to the high-flying world of trapeze. ta b l e o F CONTENTS about dance Films association 4 Welcome 6 about dance on camera Festival 8 dance in Focus aWards 11 g a l l e ry e x h i b i t 13 Free events 14 special events 16 opening and closing programs 18 main slate 20 Full schedule 26 s h o r t s p r o g r a m s 32 cover: Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers in Kinetic Molpai, ca. 1935 courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow Dance festival archives this Page: The Dance Goodbye ron steinman back cover: Feelings are Facts: The Life of Yvonne Rainer courtesy estate of warner JePson ABOUT DANCE dance Films association dance Films association and dance on camera board oF directors Festival staFF Greg Vander Veer Nancy Allison Donna Rubin Interim Executive Director President Virginia Brooks Liz Wolff Co-Curator Dance on Camera Festival Paul Galando Brian Cummings Joanna Ney Co-Curator Dance on Camera Festival Vice President and Chair of Ron -

Mean Girls? the Influence of Gender Portrayals in Teen Movies on Emerging Adults' Gender-Based Attitudes and Beliefs

MEAN GIRLS? THE INFLUENCE OF GENDER PORTRAYALS IN TEEN MOVIES ON EMERGING ADULTS' GENDER-BASED ATTITUDES AND BELIEFS By Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz and Dana E. Mastro This two-part exploratory study utilized a social cognitive theory frame- work in documenting gender portrayals in teen movies and investigating the influence of exposure to these images on gender-based beließ about friendships, social aggression, and roles of women in society. First, a con- tent analysis of gender portrayals in teen movies was conducted, reveal- ing that female characters are more likely to be portrayed as socially aggressive than male characters. Second, college students were surveyed about their teen movie-viewing habits, gender-related beliefs, and atti- tudes. Findings suggest that viewing teen movies is associated with neg- ative stereotypes about female friendships and gender roles. Research examining the effects of media exposure demonstrates that media consumption has a measurable influence on people's per- ceptions of the real world, and, regardless of the accuracy of these per- ceptions, they are used to help guide subsequent attitudes, judgments, and actions. For example, these results have been yielded for view- ing media representations of race,' the mentally ill,^ and the elderly.^ Past research additionally indicates that watching televised gender portrayals has an effect on individuals' real-world gender-based atti- tudes, beliefs, and behaviors."* Based on this research, and the tenets of social cognitive theory, it would be expected that consumption of teen movies would have an analogous influence on audience members' gen- der-based attitudes and beliefs. Despite the popularity of teen movies, the influence of such films on emerging adults has not been examined. -

Motion Picture

Moving Images Prepared by Bobby Bothmann RDA Moving Images by Robert L. Bothmann is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Created 2 February 2013 Modified 11 November 2014 https://link.mnsu.edu/rda-video Scope Step-through view of the movie Hairspray from 2007 Generally in RDA rule order Uses MARC 21 examples Describing Manifestations & Items Follows RDA Chapters 2, 3, 4 Describing Works and Expressions Follows RDA Chapters 6, 7 Recording Attributes of Person & Corporate Body Uses RDA Chapters 9, 11, 18 Covers relator terms only Recording Relationships Follows RDA Chapters 24, 25, 26 2 Resources Olson, Nancy B., Robert L. Bothmann, and Jessica J. Schomberg. Cataloging of Audiovisual Materials and Other Special Materials: A Manual Based on AACR2 and MARC 21. Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited, 2008. [Short citation: CAVM] Online Audiovisual Catalogers, Inc. Cataloging Policy Committee. Streaming Media Best Practices Task Force. Best Practices for Cataloging Streaming Media. No place : OLAC CAPC, 2009. http://olacinc.org/drupal/capc_files/streamingmedia.pdf Online Audiovisual Catalogers, Inc. Cataloging Policy Committee. DVD Cataloging Guide Update Task Force. Guide to Cataloging DVD and Blu-ray Discs Using AACR2r and MARC 21. 2008 Update. No place: OLAC CAPC, 2008. http://olacinc.org/drupal/capc_files/DVD_guide_final.pdf Pan-Canadian Working Group on Cataloguing with RDA. “Workflow: Video recording (DVD) RDA.” In RDA Toolkit | Tools| Workflows |Global Workflows. 3 Preferred Source 4 5 Title Proper 2.3.2.1 RDA CORE the chief name of a resource (i.e., the title normally used when citing the resource). 245 10 $a Hairspray Capitalization is institutional and cataloger’s choice Describing Manifestations 6 Note on the Title Proper 2.17.2.3 RDA Make a note on the source from which the title proper is taken if it is a source other than: a) the title page, .. -

WORK IT 18.8.10 Alison Peck

WORK IT Written by Alison Peck 8.10.18 STX Entertainment Alloy Entertainment AK Worldwide Prods FADE IN: OVER CREDITS: CLOSE UP of DANCERS’ FEET as they STOMP the pavement while an upbeat, hip hop BANGER picks up. Rhythmically, fast. Bursting with style. Now we see other FEET on a STAGE. They SPIN, they SLIDE, they STOMP in unison. Mesmerizing. And then, BOOM. Girl’s feet-- A pair of plain white Keds move down a hallway. Passing by much cooler kicks belonging to much cooler people. We’re in-- INT. HIGH SCHOOL HALLWAY - DAY The feet move across the dirty floor, passing backpacks, lockers. And we PULL BACK TO REVEAL-- The lovely face of QUINN ACKERMAN, 18, the one wearing those Keds. Big glasses, vintage baggy Stanford sweater. Her vibe is intense-phD-student-working-on-her-dissertation. Out-of- place in high school. A modern Brat Pack Molly Ringwald, a post-Millennial Annie Hall. The most interesting person here, but no one knows it yet. SOME DUDE is horse-playing, doesn’t see Quinn, and BODY-SLAMS into her. She SMASHES into the lockers, FALLS to the floor, GROANS-- “what the fuck?” QUINN Come on, man! SOME DUDE Eat my dick, Einstein! QUINN I’d have to find it first! As she collects her fallen books, ANOTHER STUDENT shoots a look in her direction. QUINN (CONT’D) I know, I know. I shouldn’t emasculate... Though then again, why’s it my responsibility as a woman to protect a man’s fragile masculinity-- 2. ANOTHER STUDENT --You’re blocking my shit. -

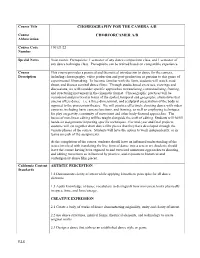

Choreography for the Camera AB

Course Title CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA A/B Course CHORFORCAMER A/B Abbreviation Course Code 190121/22 Number Special Notes Year course. Prerequisite: 1 semester of any dance composition class, and 1 semester of any dance technique class. Prerequisite can be waived based-on comparable experience. Course This course provides a practical and theoretical introduction to dance for the camera, Description including choreography, video production and post-production as pertains to this genre of experimental filmmaking. To become familiar with the form, students will watch, read about, and discuss seminal dance films. Through studio-based exercises, viewings and discussions, we will consider specific approaches to translating, contextualizing, framing, and structuring movement in the cinematic format. Choreographic practices will be considered and practiced in terms of the spatial, temporal and geographic alternatives that cinema offers dance – i.e. a three-dimensional, and sculptural presentation of the body as opposed to the proscenium theatre. We will practice effectively shooting dance with video cameras, including basic camera functions, and framing, as well as employing techniques for play on gravity, continuity of movement and other body-focused approaches. The basics of non-linear editing will be taught alongside the craft of editing. Students will fulfill hands-on assignments imparting specific techniques. For mid-year and final projects, students will cut together short dance film pieces that they have developed through the various phases of the course. Students will have the option to work independently, or in teams on each of the assignments. At the completion of the course, students should have an informed understanding of the issues involved with translating the live form of dance into a screen art. -

HYPE-34-Genesis.Pdf

Exclusive benefits for Students and NSFs FREE Campus/Camp Calls Unlimited SMS Incoming Calls Data Bundle Visit www.singtel.com/youth for details. Copyright © 2012 SingTel Mobile Singapore Pte. Ltd. (CRN : 201012456C) and Telecom Equipment Pte. Ltd. (CRN: 198904636G). Standard SingTel Mobile terms and conditions apply. WHERE TO FIND HYPE COMPLIMENTARY COPIES OF HYPE ARE AVAILABLE AT THE FOLLOWING PLACES Timbre @ The Arts House Island Creamery Swirl Art 1 Old Parliament Lane #01-04 11 King Albert Park #01-02 417 River Valley Road Timbre @ The Substation Serene Centre #01-03 1 Liang Seah Street #01-13/14 45 Armenian Street Holland Village Shopping Mall #01-02 Timbre @ Old School The Reckless Shop 11A Mount Sophia #01-05 Sogurt Orchard Central #02-08/09 617 Bukit Timah Road VivoCity #02-201 Cold Rock Blk 87 Marine Parade Central #01-503 24A Lorong Mambong DEPRESSION 313 Somerset #02-50 Leftfoot Orchard Cineleisure #03-05A 2 Bayfront Avenue #B1-60 Far East Plaza #04-108 Millenia Walk Parco #P2-21 Orchard Cineleisure #02-07A BooksActually The Cathay #01-19 Beer Market No. 9 Yong Siak Street, Tiong Bahru 3B River Valley Road #01-17/02-02 Once Upon a Milkshake St Games Cafe 32 Maxwell Road #01-08 Strictly Pancakes The Cathay #04-18 120 Pasir Ris Central #01-09 44A Prinsep Street Frolick Victoria Jomo Ice Cream Chefs Lot One #B1-23 9 Haji Lane Ocean Park Building, #01-06 Hougang Mall #B1-K11 47 Haji Lane 12 Jalan Kuras (Upper Thomson) 4 Kensington Park Road Tampines 1 #B1-32 VOL.TA Marble Slab 241 Holland Avenue #01-02 The Cathay #02-09 Iluma -

Waacking Is a Style of Dance That Came up in the 70'S, Coming Directly from the Funk & Disco Era

Waacking is a style of dance that came up in the 70's, coming directly from the Funk & Disco era. It was born in gay clubs, but through television show, it became popular. Waacking is now starting to resurface and it's popularity is starting to grow. This dance allows you to create a personal style; doesn't matter whether it be sexy, feminine or aggressive, as long as you express yourself and let yourself go to the music. Movements of the performers were so creative. This style is often wrongly considered a style oh house dance. Disco music was the perfect vehicle for this style, with its driving rhythms and hard beats. In the early 1970s in Los Angeles, dancer Lamont Peterson was one of the first to start using his arms and body to the music. Dancer such Mickey Lord, Tyrone Proctor and Blinky fine tuned the arms movements, by making the arms and hands go fast to the driving disco beat. At the time waacking was primarily a gay black and latino dance. Many people mistakenly believe that waacking came from Locking becouse some movements are very similar. the gay community is soley responsible for the creation of this style. Waacking and Lockinghave some similarities but they are different dances. Waacking is the original name; Punking is a name set forth by non gay community that mixed in movements from Locking. The Name originated from Tyrone Proctor and Jeffrey Daniel's. Garbo in another name given to the dance. The difference between Waacking and Voguins is the first became popular in the 1970's on the West Coast.