Using-Rizq-For-Justice -A-Muslim-Response-To-The-Uyghur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Uyghur Genocide

EARNING YOUR TRUST, EVERY DAY. 08.14.21 VOLUME 36 NUMBER 15 “AN INDUSTRY EXISTS BECAUSE THERE IS A MARKET FOR IT.” —THE GROWING SERMON-PREP INDUSTRY, P. 38 P. INDUSTRY, SERMON-PREP GROWING —THE IT.” FOR MARKET A IS THERE BECAUSE EXISTS INDUSTRY “AN THE UYGHUR GENOCIDE P.44 v36 15 COVER+TOC.indd 1 7/27/21 10:57 AM WHAT IS DONE FOR GOD’S GLORY WILL ENDURE FOREVER. RIGHT NOW COUNTS FOREVER LEARN HOW TO LIVE ALL OF LIFE IN LIGHT OF ETERNITY TODAY. LIGONIER.ORG/LEARN v36 15 COVER+TOC.indd 2 7/27/21 12:00 PM FEATURES 08.14.21 VOLUME 36 NUMBER 15 50 LIFE AND NEW LIFE Ultrasound technology is a powerful tool against the culture of death—but it has its limits by Leah Savas 38 44 58 SERMONS TO GO ERASING THE UYGHURS CHRONICLING THE PRO-LIFE Plagiarism controversies bring attention Testimonies and research at a United MOVEMENT to a question pastors face when Kingdom tribunal paint a harrowing WORLD’s coverage of the battle for the preparing material for the pulpit: picture of China’s intentions to assimilate unborn highlights the highs and lows of a How much borrowing is too much? the ethnic group by force movement with often unexpected allies by Jamie Dean by June Cheng by Leah Savas PHOTO BY LEE LOVE/GENESIS 08.14.21 WORLD v36 15 COVER+TOC.indd 1 7/28/21 8:47 AM DEPARTMENTS 08.14.21 VOLUME 36 NUMBER 15 5 MAILBAG 6 NOTES FROM THE CEO 65 Bowe Becker swims in the 4x100 freestyle relay final during the Tokyo Olympics. -

Chapter Ii Uniqlo Company Profile and the Network in China

CHAPTER II UNIQLO COMPANY PROFILE AND THE NETWORK IN CHINA In this chapter the author will focus on the discussion of the company profile of UNIQLO as a research subject which is one of the world's leading fast fashion companies. The author wants to show how UNIQLO stands and becomes a company that is expanding globally throughout the world. The author will also explain the network of UNIQLO in China. A. UNIQLO Company History and Profile After World War II ended, precisely in 1949, was the beginning of UNIQLO establishment. At that time the company was founded by Hitoshi Yanai who is the father of the current managing director Tadashi Yanai opened a men's clothing store named Ogori Shoji in Ube City, Yamaguchi Prefecture. In 1984 precisely when Tadashi Yanai was an adult, he founded a shop that sells casual clothing under the name Unique Clothing Warehouse in Hiroshima City.30 The name "UNIQLO" itself arises from the combination of the words "Unique Clothing". The main aim of the UNIQLO company is to inspire the world by casual dress. In taking the name UNIQLO, the company has the brand philosophy "Made for All" as the company's slogan. In 1991 Tadashi Yanai changed the name of his father's company "Ogori Shōji" to "Fast Retailing". 30 Staff abyad apparel pro. (2019, September 3). Sejarah Tentang Uniqlo Dan Perkembangannya Di Indonesia. Retrieved From Abyad Apparel Pro: http://abyadscreenprinting.com/sejarah-uniqlo-dan- perkembangannya/ 18 2.1The First UNIQLO Store Before the 1990s, UNIQLO was not a product known to the wider community, Japanese people tended to see well-known brands and of course that could elevate their prestige. -

Download the Covid Fashion Report

E H T COVID FASHION REPORT A 2020 SPECIAL EDITION OF THE ETHICAL FASHION REPORT THE COVID FASHION REPORT A 2020 SPECIAL EDITION OF THE ETHICAL FASHION REPORT Date: October 2020 Australian Research Team: Peter Keegan, Chantelle Mayo, Bonnie Graham, Alexandra Turner New Zealand Research Team: Annie Newton-Jones, Claire Gray Report Design: Susanne Geppert Infographics: Susanne Geppert, Matthew Huckel Communications: Samara Linehan Behind the Barcode is a project of Baptist World Aid Australia. New Zealand headquartered companies researched in partnership with Tearfund New Zealand. www.behindthebarcode.org.au Front cover photo: KB Mpofu, ILO via Flickr CONTENTS PART ONE PART TWO PART THREE The COVID Challenge COVID Fashion Actions & Commitments Recommendations The 2020 Special Edition .......................5 1: Support Workers’ Wages by Industry Action ....................56 .... COVID Fashion Commitments ................7 Honouring Supplier Commitments 19 Consumer Action.................57 Industry Response to COVID-19 ..............8 2: Identify and Support the Workers at Greatest Risk .......... 26 COVID-19 and Garment Workers ...........10 COVID-19 and Consumers .................... 11 3: Listen to the Voices and Experience of Workers ............. 32 COVID-19 and Fashion Companies ........13 Appendices 4: Ensure Workers’ Rights Methodology .....................................14 and Safety are Respected ............... 39 Fashion Company-Brand Company Fashion Tiers .......................17 Reference List 59 5: Collaborate with Others Endnotes 64 to Protect Vulnerable Workers ......... 46 About Baptist World Aid 6: Build Back Better for Workers Australia 66 and the World ............................... 50 Acknowledgements 67 Part One THE COVID CHALLENGE THE 2020 SPECIAL EDITION 2020 has been a year like no other. COVID-19 has swept across the planet, sparking subsequent health, economic, and humanitarian crises. -

IPAC Q&A: Backbench Business Debate on Uyghur Genocide

Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China Q&A: Backbench Business debate on Uyghur Genocide Motion “That this House believes that Uyghurs and other ethnic and religious minorities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region are suffering Crimes Against Humanity and Genocide.” And calls upon the Government to act to fulfil their obligations under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide and all relevant instruments of international law to bring it to an end. (Nusrat Ghani MP) Details Thursday 22nd April 2021, Chamber Context The publishing of two independent legal analyses has added to mounting evidence suggesting that the gross human rights abuses being perpetrated against the Uyghurs and other ethnic and religious minorities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China (XUAR) constitute Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. What is the evidence that a Genocide is taking place against Uyghurs? Two major independent analyses have investigated reports of alleged genocide in the Xinjiang region: ● A formal legal opinion published by Essex Court Chambers in London, which concludes that there is a “very credible case” that the Chinese government is carrying out the crime of Genocide against the Uyghur people. ● A report from the Newlines Institute for Strategy and Policy, conducted by over 30 independent global experts, which finds that the Chinese state is in breach of every act prohibited in Article II of the Genocide Convention. Both reports conclude there is sufficient evidence that the prohibited acts specified within the Genocide Convention and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court have been breached with respect to the Uyghurs, namely: 1. -

Correspondence with Uniqlo

Rt Hon Tom Tugendhat MP Rt Hon Nusrat Ghani MP Rt Hon Darren Jones MP Chair, Foreign Affairs Committee Business, Energy and Chair, Business, Energy and House of Commons Industrial Strategy Committee Industrial Strategy Committee London SW1A 0AA House of Commons House of Commons London SW1A 0AA London SW1A 0AA 23 November 2020 Dear Mr Tugendhat, Ms Ghani and Mr Jones, Thank you for your letter dated 9 November 2020 regarding UNIQLO supply chain which reportedly includes materials and labour sourced from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China. UNIQLO appreciate your enquiry as we take matters of human rights and ethical responsibilities seriously. We have worked closely with the relevant sections of our business including our parent company Fast Retailing based in Japan to provide detailed responses to your questions, as follows: 1. What is the nature and extent of your company’s operations in Xinjiang? UNIQLO does not own or directly operate any factories as part of its business. Additionally, no UNIQLO product is manufactured in the Xinjiang region by any of our production partners, and none of our production partners subcontract to fabric mills or spinning mills in the region. 2. What specific raw materials arriving in UK markets are sourced from Xinjiang? UNIQLO sources sustainable cotton*1, and this includes cotton originating in China. By definition, sustainable cotton is that which ensures human rights and good working environments, in accordance with international standards. Sustainable cotton forbids the use of both forced labour and child labour at farms. *1 Sustainable cotton refers to Better Cotton*2 sources; cotton sourced from the United States or Australia, recycled cotton*3; organic cotton*4; Fair Trade cotton; and Cotton made in Africa (CmiA). -

Uyghur Concentration Camp Survivor Testimonies

7- 13 June 2021 Weekly Journal of Press New Horrors: Uyghur Concentration Camp Survivor Testimonies CJ Werleman, June 10 Two dozen Uyghur concentration camp survivors, relatives of detainees and former Chinese guards gave testimony to the Uyghur Tribunal over four days, from June 4 to 7. Herewith a summary of the more sho- cking testimonies: Abduweli Ayup I was born in Kashgar city, China, in 1973. I am currently residing in Tur- key. I was detained by the local Chinese State Security Police from August 19th, 2013 until November 20th, 2014. The reason was because I was promoting, online, the linguistic rights of Uyghur people and in the process of opening They asked me to take off my whole clothes and two kindergartens in the Uyghur mot- they asked me to bow. Just like a dog, dog style. her tongue in Urumqi and Kashgar. Then the sexual abuse happened. At first, they threatened me to life imp- Read more of his testimony here: https:// risonment. And then they used an ele- uyghurtribunal.com/wp-content/uploa- ctric stick. They shocked my right arm ds/2021/06/04-1710-JUN-21-UTFW-013-Abduwe- and once in the armpit. This is in the li-Ayup-English-1.pdf interrogation room. And then they ac- cused me of being a spy for the CIA and Sayragul Sauytbay for instigating separatism and inciting I was told that I would be teaching detainees at the people to break Chinese language po- education centre. My first impression of the centre licy. was that it was a scary fascist camp. -

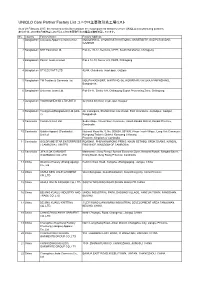

UNIQLO Core Partner Factory List ユニクロ主要取引先工場リスト

UNIQLO Core Partner Factory List ユニクロ主要取引先工場リスト As of 28 February 2017, the factories in this list constitute the major garment factories of core UNIQLO manufacturing partners. 本リストは、2017年2月末時点におけるユニクロ主要取引先の縫製工場を掲載しています。 No. Country Factory Name Factory Address 1 Bangladesh Colossus Apparel Limited unit 2 MOGORKHAL, CHOWRASTA NATIONAL UNIVERSITY, GAZIPUR SADAR, GAZIPUR 2 Bangladesh NHT Fashions Ltd. Plot no. 20-22, Sector-5, CEPZ, South Halishahar, Chittagong 3 Bangladesh Pacific Jeans Limited Plot # 14-19, Sector # 5, CEPZ, Chittagong 4 Bangladesh STYLECRAFT LTD 42/44, Chandona, Joydebpur, Gazipur 5 Bangladesh TM Textiles & Garments Ltd. MOUZA-KASHORE, WARD NO.-06, HOBIRBARI,VALUKA,MYMENSHING, Bangladesh. 6 Bangladesh Universal Jeans Ltd. Plot 09-11, Sector 6/A, Chittagong Export Processing Zone, Chittagong 7 Bangladesh YOUNGONES BD LTD UNIT-II 42 (3rd & 4th floor) Joydevpur, Gazipur 8 Bangladesh Youngones(Bangladesh) Ltd.(Unit- 24, Laxmipura, Shohid chan mia sharak, East Chandona, Joydebpur, Gazipur, 2) Bangladesh 9 Cambodia Cambo Unisoll Ltd. Seda village, Vihear Sour Commune, Ksach Kandal District, Kandal Province, Cambodia 10 Cambodia Golden Apparel (Cambodia) National Road No. 5, No. 005634, 001895, Phsar Trach Village, Long Vek Commune, Limited Kompong Tralarch District, Kompong Chhnang Province, Kingdom of Cambodia. 11 Cambodia GOLDFAME STAR ENTERPRISES ROAD#21, PHUM KAMPONG PRING, KHUM SETHBO, SROK SAANG, KANDAL ( CAMBODIA ) LIMITED PROVINCE, KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA 12 Cambodia JIFA S.OK GARMENT Manhattan ( Svay Rieng ) Special Economic Zone, National Road#, Sangkat Bavet, (CAMBODIA) CO.,LTD Krong Bavet, Svay Rieng Province, Cambodia 13 China Okamoto Hosiery (Zhangjiagang) Renmin West Road, Yangshe, Zhangjiagang, Jiangsu, China Co., Ltd 14 China ANHUI NEW JIALE GARMENT WenChangtown, XuanZhouDistrict, XuanCheng City, Anhui Province CO.,LTD 15 China ANHUI XINLIN FASHION CO.,LTD. -

GREAT CLOTHES CAN CHANGE OUR WORLD Is a Global Company That Operates Multiple Fashion Brands Including UNIQLO, GU, and Theory

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Year ended 31 August 2018 GREAT CLOTHES CAN CHANGE OUR WORLD is a global company that operates multiple fashion brands including UNIQLO, GU, and Theory. The world’s third largest manufacturer and retailer of private-label apparel, Fast Retailing offers high-quality, reasonably priced clothing by managing everything from procurement, design, and production to retail sales. UNIQLO, our pillar brand, generates approximately ¥1.76 trillion in sales from 2,068 stores in 21 countries and regions (FY2018). UNIQLO, with its LifeWear concept of ultimate everyday comfort, differentiates itself by offering unique products such as sweaters made from superior-quality cashmere, supima cotton T-shirts, and ranges incorporating original HEATTECH and Ultra Light Down technologies. The Group’s main sources of UNIQLO-driven growth are moving beyond Japan to Greater China (Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan) and Southeast Asia. Our fun, low-priced fashion brand GU has generated sales of approximately ¥210 billion, primarily in Japan. We expect to grow the GU brand in Greater China and South Korea going forward. Fast Retailing is making progress on its Ariake Project, which aims to transform the apparel retail industry into a new digital consumer retail industry. We are working to build a supply chain that uses advanced information technology to create seamless links between Fast Retailing and its partner factories, warehouses, and stores worldwide. This transformation will minimize the environmental impact of our business, create a manufacturing environment that upholds human rights, and ensure highly responsible procurement. Fast Retailing strives to harness the power of clothing to enrich the lives of people around the world, and create a more sustainable society. -

Performance Analysis of China's Fast Fashion Clothing Market Based on SCP Model

Open Journal of Business and Management, 2019, 7, 106-115 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojbm ISSN Online: 2329-3292 ISSN Print: 2329-3284 Performance Analysis of China’s Fast Fashion Clothing Market Based on SCP Model Lu Ge1, Xuran Sun1, Chenggang Li2* 1Department of Business Administration, Fashion Brand Management, Business School of BIFT, Beijing, China 2Department of Network Economy, Electronic Business, Network Marketing, Management Innovation, Business School of BIFT, Beijing, China How to cite this paper: Ge, L., Sun, X.R. Abstract and Li, C.G. (2019) Performance Analysis of China’s Fast Fashion Clothing Market China’s fast fashion clothing market is dominated by Uniqlo, ZARA and H & Based on SCP Model. Open Journal of Busi- M, supplemented by other fast fashion clothing brands. This paper uses SCP ness and Management, 7, 106-115. paradigm to analyze the fast fashion brands in China’s clothing market. By https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2019.71007 dividing the market structure of China’s fast fashion clothing, it is concluded Received: November 15, 2018 that the market structure of China’s fast fashion clothing is oligopoly III, and Accepted: December 16, 2018 the cost oriented price behavior of enterprises in the oligopoly market struc- Published: December 19, 2018 ture is analyzed. In order to analyze the market performance of China’s fast Copyright © 2019 by authors and fashion clothing market, digital non-price behavior and organizational ad- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. justment behavior of increasing the number of stores are used to analyze the This work is licensed under the Creative market performance of China’s fast fashion clothing market. -

Download Article (PDF)

RECENT PUBLICATIONS ON SYRIAC TOPICS: 2018* SEBASTIAN P. BROCK, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD GRIGORY KESSEL, AUSTRIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER SERGEY MINOV, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD Books Acharya, F., Psalmic Odes from Apostolic Times: An Indian Monk’s Meditation (Bengaluru: ATC Publishers, 2018). Adelman, S., After Saturday Comes Sunday (Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press, 2018). Alobaidi, T., and Dweik, B., Language Contact and the Syriac Language of the Assyrians in Iraq (Saarbrücken, Germany: Lambert Academic Publishing, 2018). Andrade, N.J., The Journey of Christianity to India in Late Antiquity: Networks and the Movement of Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018). Aravackal, R., The Mystery of the Triple Gradated Church: A Theological Analysis of the Kṯāḇā d-Massqāṯā (Book of Steps) with Particular Reference to the Writing of Aphrahat and John the Solitary (Oriental Institute of Religious Studies India Publications 437; Kottayam, India: Oriental Institute of Religious Studies, 2018). Aydin, G. (ed.), Syriac Hymnal According to the Rite of the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch (Teaneck, New Jersey: Beth Antioch Press / Syriac Music Institute, 2018). Bacall, J., Chaldean Iraqi American Association of Michigan (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2018). * The list of publications is based on the online Comprehensive Bibliography on Syriac Christianity, supported by the Center for the Study of Christianity at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (http://www.csc.org.il/db/db.aspx?db=SB). Suggested additions and corrections can be sent to: [email protected] 235 236 Bibliographies Barry, S.C., Syriac Medicine and Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq’s Arabic Translation of the Hippocratic Aphorisms (Journal of Semitic Studies Supplement 39; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018). -

Celebrating Our Second Store in Illinois! 5 Woodfield Mall, Schaumburg, IL 60173 Photo Shown: UNIQLO Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL This Is Lifewear

Celebrating our second store in Illinois! 5 Woodfield Mall, Schaumburg, IL 60173 Photo shown: UNIQLO Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL This Is LifeWear Who you are, what you believe in: that’s what you wear every day. And that is what we make clothing for. Welcome to a new way of apparel. Apparel that comes from our Japanese values of simplicity, quality and longevity. Designed to be of the time and for the time. Made with such modern elegance that it becomes the building blocks of your style. A perfect shirt that is always being made more perfect. The simplest design hiding the most thoughtful and modern details. The best in fit and fabric made to be affordable and accessible to all. Clothing that we are constantly innovating, bringing more warmth, more lightness, better design, and better comfort to your life. It never stops evolving because your life never stops changing. Simple apparel with a not-so-simple purpose: to make your life better. Uniqlo LifeWear. Simple made better. Extra Fine Merino The luxurious texture and quality you’ll know MEN as soon as you touch it. Known worldwide as the Extra Fine Merino best in merino wool. Woven for warmth. V-Neck Sweater WOMEN $39.90 Extra Fine Merino Crew Neck Sweater $29.90 WOMEN 3D Extra Fine Merino Ribbed Turtleneck Long-Sleeve Dress $59.90 Made with 100% natural extra fine merino wool. Premium smoothness at first touch. Supremely soft and highly breathable, Made with ultra-fine fibers of just 19.5 microns for supreme softness and luster. Extra Fine Merino is a premium Luxurious Extra wool fabric that is also used in high-end suits. -

Woolworths Holdings Limited 2014 Integrated Report

WOOLWORTHS HOLDINGS LIMITED 2014 INTEGRATED REPORT WHILE OUR STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES ARE AIMED AT DRIVING GROWTH AND STAKEHOLDER VALUE, OUR GOOD BUSINESS JOURNEY ENSURES THAT WHAT WE DO IS RIGHT, BOTH SOCIALLY AND ENVIRONMENTALLY. CONTENTS 2014 HIGHLIGHTS ON A 52:52 WEEK BASIS 04 Our Integrated Report 60 Our Strategy ADJUSTED ADJUSTED RETURN ON EQUITY GROUP TURNOVER UP PROFIT BEFORE TAX UP DECREASED FROM FROM 49.5% TO 05 Our suite of reports 63 Build stronger, more profitable 05 Approval and assurance customer relationships % % % of our reports 66 Be a leading fashion retailer in 14.4 20.1 46.7 the southern hemisphere 74 Become a big food business 06 The WHL Group 78 Become an omni-channel business 80 Expand into Africa HEADLINE EARNINGS ADJUSTED HEADLINE TOTAL DIVIDEND 08 Woolworths Holdings Limited 82 Simple, convenient and rewarding PER SHARE UP EARNINGS PER SHARE UP FOR THE YEAR 10 Southern hemisphere retailer financial services 12 Our vision and values 86 Drive synergies and efficiencies % % 14 Key indicators 90 Embed the Good Business Journey 9.0 17.1 251.5 16 Strategic focus at a glance throughout our business TO 365.2 CENTS PER SHARE TO 398.0 CENTS PER SHARE CENTS PER SHARE 20 Our business model 22 Our business model and the six capitals 96 Our Governance 26 Our industry trends 32 Our stakeholders 98 Directors AVERAGE NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES NUMBER OF LOCATIONS BBBEE CONTRIBUTOR STATUS 100 Key executives 34 Our Performance 102 Governance report 111 Remuneration report 31 200 1 162 LEVEL 3 36 Our Chairman’s report 42 Our Chief Executive