Mozambique Country Report BTI 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm. -

NIGERIA E Abuja

NIGERIA e Abuja Laoos International Livestock Centre for Africa ILCA-MP/NG-2066/92 Index to livestock literature on NIGERIA Compiledby Sirak Teklu January 1992 Library and Documentation Services International Livestock Centre for Africa P 0 Box 5689, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia CONTENTS Foreword Bibliographic index v Agriculture 1 Research 1 Geography 3 History 8 Education, extension and advisory work Legislation 8 Economics 10 11 Farm organisation and management 25 Development aims, policies and programmes 34 Rural sociology 36 Distribution and marketing 45 Plant production 50 Meteorology and climatology 59 Soil biology 61 Soil chemistry and physics 63 Soil classification and genesis 66 Soil surveying and mapping 67 Soil fertility, fertilizers 67 Soil cultivation and cropping systems 71 Soil erosion and reclamation 77 Plant breeding 77 Plant ecology 79 Plant physiology and biochemistry 81 Plant taxonomy and geography 82 Protection ofplants and stored products 83 Pests of plants 84 Plant diseases 85 Weeds 86 Protection of stored products of plant and animal origin 87 Forestry production 87 Animal production 88 Animal breeding 113 Animal ecology 123 Animal untrition 125 Feed processing 149 Index to livestock literature on Nigeria Sirak Teklu Feed composition 149 Animal physiology and biochemistry 152 Animal taxonomy and geography 156 Veterinary science and hygiene 157 Pests of animals 162 Aurnal diseases 179 Miscellaneous disorders of animals 202 Fisheries production 203 Farm equipment 203 Natural resources 207 Energy resources 208 Water resources and management 208 Land resources 209 Food processing 209 Food composition 210 Auxiliary disciplines 210 Mathematics and statistics 211 Documentation 211 Subject index 213 Author index 237 List of acronyms and abbreviations 277 literature on Nigeria iv Index to livestock FOREWORD ILCA's documentation and information retrieval services cater to the needs ofAfrican livestock researchers. -

EC MOZAMBIQUE JOINT ANNUAL REPORT on 2007

JAR 2007 - OPERATIONAL REVIEW 2008 EC ─ MOZAMBIQUE JOINT ANNUAL REPORT on 2007 For the Operational Review 2008 1 Chapter 1. Executive Summary The present document is the Joint Annual Report corresponding to implementation year 2007 that the Government of Mozambique and the European Commission have agreed on in 2008, as stipulated in the Cotonou Agreement, Annex IV, Article 5. This report analyses for the year the situation in the country; describes an overview of past and current EC cooperation in Mozambique; makes an assessment on policy coherence issues; identifies actions foreseen in the 10th EDF in accordance with the priority actions of EU- Africa Action Plan agreed in December 2007 and describes dialogue in the country with the NAO and the Non State Actors. It also presents an update of the existing general donor coordination and harmonization framework, and the main conclusions on the implementation of the 9th EDF CSP. The performance of the EC cooperation can be assessed in terms of financial absorption of the available envelope; sectoral and macro-economic performance in the sectors of intervention in relation to agreed targets aligned on the PARPA II objectives and quality of dialogue. In Mozambique for the period under consideration, those three elements can be considered as globally positive. However, improvements can be made in some specific areas. The evaluation of the current CSP (9th EDF) found that EC development cooperation in Mozambique is of high quality. The effectiveness of the EC Delegation as a partner of government supporting national poverty reduction policies has improved significantly during the period 2001-2007. -

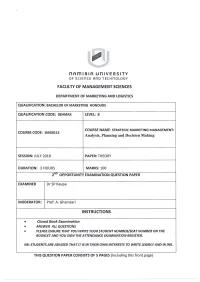

STRATEGIC MARKETING MANAGEMENT: COURSE CODE: Smg811ss Analysis, Planning and Decision Making

5 NAMIBIA UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY FACULTY OF MANAGEMENTSCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF MARKETING AND LOGISTICS QUALIFICATION: BACHELOR OF MARKETING HONOURS QUALIFICATION CODE: O8HMAR LEVEL: 8 COURSE NAME: STRATEGIC MARKETING MANAGEMENT: COURSE CODE: SMG811Ss Analysis, Planning and Decision Making SESSION: JULY 2018 PAPER: THEORY DURATION: 3 HOURS MARKS: 100 2™° OPPORTUNITY EXAMINATION QUESTION PAPER EXAMINER Dr SP Kaupa MODERATOR: Prof. A. Ghamsari INSTRUCTIONS ° Closed Book Examination e ANSWER ALL QUESTIONS e PLEASE ENSURE THAT YOU WRITE YOUR STUDENT NUMBER/SEAT NUMBERON THE BOOKLETAND YOU SIGN THE ATTENDANCE EXAMINATION REGISTER. NB: STUDENTS ARE ADVISED THATIT IS IN THEIR OWN INTERESTS TO WRITE LEGIBLY AND IN INK. THIS QUESTION PAPER CONSISTS OF 5 PAGES(Including this front page) READ THE ARTICLE BELOW AND ANSWERTHE QUESTIONS THAT FOLLOW: Real business madereal good - The story behind Steers Steers is one of the most well-known and successful quick-service restaurant brands in South Africa, with a noteworthy presence in a highly competitive fast food market. But where doestheir story begin? Their popularity and success centres on providing a range of flame grilled and value- for-money hamburgers to the consumer, while offering prospective franchisees the opportunity to be part of a lucrative franchise through its holding company, Famous Brands. Wheredoesthe story of Steers start? The history of the company revolves around the Halamandaris family, whose family members are still part of the executive team today, with extensive experience in the food and franchising industries. Steers founder, George Halamandaris had a vision to create a successful family run business and the idea for Steers originated while he was on holiday in the United States where he came across innovative food industry concepts and ideas. -

Recommendations and Conclusions from December 2019 Meeting

RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS CERF ADVISORY GROUP MEETING 5-6 DECEMBER 2019 1. The CERF Advisory Group was established by General Assembly resolution 60/124 to advise the Secretary-General, through the Under-Secretary-General (USG) for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator (ERC), on the use and impact of the fund. The second meeting of the Group in 2019 was held in New York on 5 and 6 December and was chaired by Alison Milton (Ireland). The ERC Mark Lowcock participated in two of the meeting sessions. 2. In the first session of the meeting, the Chair, the Director of the Humanitarian Financing and Resource Mobilization Division (HFRMD), Lisa Carty and the Chief of the Pooled Fund Management Branch (PFMB), Ms. Lisa Doughten welcomed five new members to the Group, including Abdul Hannan, Bangladesh, Honorary Advisor, All-Party Parliamentary Group of the Bangladesh National Parliament; Thomas Zahneisen, Germany, Director for Humanitarian Assistance, German Federal Foreign Office; Marriët Schuurman, Netherlands, Director of the Stabilisation and Humanitarian Aid Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands; Yngvild Berggrav, Norway, Policy Director, Section for Humanitarian Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Noralyn Jubaira-Baja, Philippines, Assistant Secretary, Office of United Nations and International Organizations, Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs; and Saud H. al- Shamsi, UAE, Deputy Permanent Representative, United Arab Emirates Mission to the United Nations and Amanda Magambo, Uganda, Head of Civilian Component Uganda Rapid Deployment Capability Centre (not present). The Chair presented the meeting agenda and summarized recommendations and conclusions from the Group’s meeting in June 2019. 3. The Chief of PFMB briefed on the use of the Fund during 2019. -

The Effects of Fast Food Advertisements on Young

CHILDREN’S PREFERENCES OF FAST FOOD by RCM MBOWENI - DE KLERK SHORT DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MAGISTER COMERCII in BUSINESS MANAGEMENT in the FACULTY OF MANAGEMENT at the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG Supervisor: Professor CJ JOOSTE OCTOBER 2008 ABSTRACT This study focuses on children’s preferences for fast food. In examining these preferences, the study hones in on a determination of the fast food outlet mostly preferred by children as well as an identification of the drivers, motives and reasons for the popularity of particular fast food outlets. The study also seeks to determine what the most sought after meal is and to what extent preference for a particular meal and fast food outlet are determined by the background of the child, price, the nature of the product, service levels of staff and how convenient it is to buy from the fast food outlet. The study also hones in on the influence of advertising on children’s preferences for fast food. The study makes use of a positivist (quantitative) research design. Samples were collected from four schools which composed a sample size of 301 respondents. Primary data was collected through a structured self administered questionnaire. Secondary data was collected through a literature review. Data was captured by the specialist Statistical Services Consultancy (Statscon) Department of the University of Johannesburg through the use of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Data was analysed and the findings were presented in the form of narrative reports as well as bar graphs, pie charts and cross tabulations to facilitate the ease of understanding and user friendliness. -

Proudly South African Restaurants NANDO's Is an International Casual

Proudly South African restaurants NANDO's is an international casual dining restaurant chain originating in South Africa, with a Mozambican/Portuguese theme. Founded in 1987, Nando's operates about 1,000 outlets in 30 countries. Nando's specialises in grilled chicken dishes with various peri-peri marinades. SPUR was founded by Allen Ambor (who is still the company's executive chairman) in 1967, when he opened the Golden Spur in Newlands, Cape Town. Since then, Spur has grown into an international restaurant chain with 240 South African and 29 international outlets in 2009, including restaurants Australia, Botswana, Ireland. Kenya, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, the United Arab Emirates and Zimbabwe. The company also owns the Panarotti’s pizza and pasta restaurant chain. This chain was started in 1990 and has 49 South African and 6 international outlets. In addition, the Spur Group purchased a 60% shareholding in John Dory’s Fish and Grill in 2004. John Dory's is a KwaZulu-Natal-based franchise with 22 outlets. MUGG & BEAN is a full-service, & On-The-Move restaurant, coffee-themed franchise restaurant chain originating from South Africa. The restaurant chain was founded in 1996 by Ben Filmalter after a visit to a Chicago coffee shop in the early 1990s inspired him to open a similar restaurant in South Africa. The franchise was bought by Famous Brands in 2009. As of 2015 they had 184 outlets throughout South Africa and the rest of Africa, as well as a number of overseas operations, including the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait. NEWS CAFEE is a full-service cafe-bar and cocktail franchise restaurant chain founded in South Africa. -

Potential of Meat Industry in Tanzania

POTENTIAL OF MEAT INDUSTRY IN TANZANIA Y.N.Msanga Ministry of Livestock Development and Fisheries, Tanzania P.O. Box 9152, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania 1.0 Introduction Tanzania has a large resource base of livestock that comprise of different species, breeds and types. The livestock resources include 18.8 million cattle; 13.5 million goats and 3.6 million sheep, 1.4 million pigs and 53 million poultry. Total land resource is 88.6 million hectares out of which 60 million hectares are rangelands suitable for livestock grazing, able to carry up to 20 million Livestock Units. The contribution of the livestock sector in the Gross Domestic Product is estimated at 4.7 % and contribution of livestock in the Agricultural sector is estimated at 30%. The contribution by different livestock products is 40%, 30% and 30% for beef, dairy and other stock respectively. As most of the small stocks are used for meat it adds to the fact that more than 60% of the products derived from livestock in Tanzania is meat. The contribution of livestock is not limited to its share in the total GDP but also play other important roles such as contribution to national food supply (meat, milk and eggs), and food security; acts as a source of cash income, employment and an inflation free store of value. It also provides manure and draught animal power thus contributing to sustainable agriculture. In addition, livestock play an import substitution role in the consumption of livestock products in the country. Main livestock species that are used for meat production in this country are cattle, goats, sheep, poultry, pigs and non-conventional animals. -

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles CÔTE D'ivoire

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles CÔTE D’IVOIRE by Eroarome Martin Aregheore The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The men- tion of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. All rights reserved. FAO encourages the reproduction and dissemination of material in this informa- tion product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy. © FAO 2009 3 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 5 Economic activities – agricultural sector 7 Livestock sector 8 2. SOILS AND TOPOGRAPHY 9 Soils 9 Morphology and soils of the bas-fond 10 Topography 10 3. -

Operational Review Brands Our Brands Portfolio Comprises Our Leading Brands and Our Signature Brands

LEADERSHIP COMMENTARY CONTINUED Operational review Brands Our Brands portfolio comprises our Leading brands and our Signature brands. The Leading (mainstream) brands portfolio is segmented into Quick Service, Fast Casual and Casual Dining brands. Several of our Signature (niche) brands are JV partnerships with the founders of the respective brands. Our brands are represented through a network of 2 791 franchised and 107 Company-owned restaurants in SA, the AME region and the UK. SA Salient features Leading brands Signature brands 2020 2019 2020 2019 Segment revenue (%) 80.4 83.7 19.6 16.3 Like-for-like sales growth (%) 3.5 2.9 (0.8) (0.6) Operating margin (%) 57.4 61.1 12.0 12.8 Total number of restaurants 2 290 2 244 151 158 New restaurants opened 81 125 11 32 Number of restaurants revamped 260 238 2 5 Number of restaurants closed 34 53 17 20 Leading brands portfolio: Quick Service Our Leading Quick Service brands are those that prioritise take away and delivery offerings. While these restaurants offer a limited sit-down option, their focus is on quick service. The brands in this segment are: Steers, Debonairs Pizza, Fishaways and Milky Lane. While Wakaberry and Giramundo remain part of the Leading brands’ results, they are not reported on and are in the final stages of being rationalised. The commentary which follows outlines the key developments and initiatives, awards and areas of future focus for each of our Leading brands. We have also rated the performance of each brand in the review period against our FY2020 areas of focus and targets. -

Mapping Animal Traction Suitability in Rural Mozambique

April 2016 • Research Paper 79E Exploiting the potential for expanding cropped area using animal traction in the smallholder sector in Mozambique Benedito Cunguara David Mather Tom Walker Bordalo Mouzinho Jaquelino Massingue Rafael Uaiene Benedito Cunguara and David Mather are research associate and assistant professor, respectively, Michigan State University; Tom Walker is an independent researcher; Bordalo Mouzinho is a graduate student at the University of Tokyo; Jaquelino Massingue and Rafael Uaiene are research analyst and assistant professor, respectively, Michigan State University. DIRECTORATE OF PLANNING AND INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION Research Paper Series The Directorate of Planning and International Cooperation of the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security maintains two publication series for research on food security issues. Publications under the Flash series are short (3-4 pages), carefully focused reports designated to provide timely research results on issues of great interest. Publications under the Research Paper series are designed to provide longer, more in-depth treatment of food security issues. The preparation of Flash and Research Papers, and their discussion with those who design and influence programs and policies in Mozambique, is an important step in the Directorate’s overall analyses and planning mission. Comments and suggestion from interested users on reports under each of these series help identify additional questions for consideration in later data analyses and report writing, and in the design of further research activities. Users of these reports are encouraged to submit comments and inform us of ongoing information and analysis needs. Raimundo Matule National Director Directorate of Planning and International Cooperation Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security Recommended citation: Cunguara, B., Mather, D., Walker, T., Mouzinho, B, Massingue, J., and Uaiene, R., 2016. -

Iirn ~Rn WU and SUN,,,M., (Tw +

IMUOGROW DATA NM T ,.o. WUiirn AND SUN,,,M.,~rn (tW - I EW-AAJ-28_+ hLOO-0OOO-G 204 The economics of cattle and meat marketing in Ivory Coast ,PIRIOKAL AUNSM (Is"! Staatz, Ja M. ".CORPORAT. A-iDR, S (10i) Mich. Univ. Ctr. for Research on Economic Development 6. DOCUMENT DATE (110) NUPj 07.OV PAGES (120) 8. ARC MNM (170) 1979 617p. 1V338.1762. S775 9. REFERENCE ORGANIZATION (130) Mich. 10. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES (500) 11. ABSTRACT (950) 12. DM.SCI JTORS (920) 1&roWT Ntn"Im (I") Ivory Coast Meat Cattlei Cattla marketing Supply Transportatlt n I4L IONTRAtr 1M1 f*) I CONTRACT Infrastructure Prices AID/afr-C-1169 TYM(140 Cost analysis Policies - Ag.:icultural ecoromics IT.TY1WI1 DOCOEIW (3I5 21 THE ECONOMICS OF CATTLE AND MEAT MARKETING IN IVORY COAST by John M. Staatz Research Associate Center for Research on Economic Development University of Michigan Chercheur Associ6 Centre Ivorien de Recherche Economique et Sociale Universit6 Nationale de C6te d'Ivoire 6 9 AID/afr-C-tI (1979@ 10R WORD Traditional marketing systems for agricultural products in developing nations have often been accused of driving an unnecessarily large price differential between producers and consumers to the detriment of both. Some critics claim there are too many marketing agents forcing too many intermediate transactions. Others argue that small numbers of traders collude'to exercise oligopsonistic power over producers and oligopolistic power over consumers. Marketing agents are frequently labeled as parasites who serve no useful function. Many developing nations have responded to these criticisms with strict regulation or complete take-over of agricultural marketing.