The Effects of Fast Food Advertisements on Young

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Youth Group Procedures 2014-2015 Youth Group Sales Business Hours: 1-800-YOUTH-15 Monday Thru Friday 8:30Am to 5:00Pm Est

Youth Group Procedures 2014-2015 Youth Group Sales Business Hours: 1-800-YOUTH-15 Monday thru Friday 8:30am to 5:00pm est www.UniversalOrlandoYouth.com Making and Confirming Reservations • Complete the Youth Ticket Order Form and email the completed form to: [email protected] or fax to 407-224-5954 • Your order form must be accompanied by a written request on school/organization letterhead that includes contact person name and signature. • Completed forms must be received two weeks prior to visit date. • Ticket Reservations will provide you with a confirmation number and invoice via email within 5 business days To check the status of your order or to make any changes to your order please call 407-363-8182 Payment Send Payments to: Universal Orlando Attn: Youth Markets B110-2 Universal Orlando 1000 Universal Studios Plaza Orlando, FL 32819 • Advance Payment (preferred): Tickets paid in advance (4 weeks before visit date) are eligible to be sent via Fed Ex Credit card or company/organization check payments are accepted Credit card authorization form must be completed for each credit card purchase and faxed to 407-224-5954 • Unacceptable Forms of Payment Personal Checks Purchase Order/Payment Voucher Third Party Checks Counter Checks or altered checks Group Sales Window (Ticket Pick-Up) • Tickets can be paid and picked up at either • Universal Studios Florida® Group Sales window (between 8am and 4pm), 7 days a week. • Islands of Adventure ® Group Sales window (between 8am and 2pm) , 7 days a week. • Please be prepared with your confirmation number and a valid photo ID of the pick up person indicated on the youth ticket order form. -

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm. -

NIGERIA E Abuja

NIGERIA e Abuja Laoos International Livestock Centre for Africa ILCA-MP/NG-2066/92 Index to livestock literature on NIGERIA Compiledby Sirak Teklu January 1992 Library and Documentation Services International Livestock Centre for Africa P 0 Box 5689, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia CONTENTS Foreword Bibliographic index v Agriculture 1 Research 1 Geography 3 History 8 Education, extension and advisory work Legislation 8 Economics 10 11 Farm organisation and management 25 Development aims, policies and programmes 34 Rural sociology 36 Distribution and marketing 45 Plant production 50 Meteorology and climatology 59 Soil biology 61 Soil chemistry and physics 63 Soil classification and genesis 66 Soil surveying and mapping 67 Soil fertility, fertilizers 67 Soil cultivation and cropping systems 71 Soil erosion and reclamation 77 Plant breeding 77 Plant ecology 79 Plant physiology and biochemistry 81 Plant taxonomy and geography 82 Protection ofplants and stored products 83 Pests of plants 84 Plant diseases 85 Weeds 86 Protection of stored products of plant and animal origin 87 Forestry production 87 Animal production 88 Animal breeding 113 Animal ecology 123 Animal untrition 125 Feed processing 149 Index to livestock literature on Nigeria Sirak Teklu Feed composition 149 Animal physiology and biochemistry 152 Animal taxonomy and geography 156 Veterinary science and hygiene 157 Pests of animals 162 Aurnal diseases 179 Miscellaneous disorders of animals 202 Fisheries production 203 Farm equipment 203 Natural resources 207 Energy resources 208 Water resources and management 208 Land resources 209 Food processing 209 Food composition 210 Auxiliary disciplines 210 Mathematics and statistics 211 Documentation 211 Subject index 213 Author index 237 List of acronyms and abbreviations 277 literature on Nigeria iv Index to livestock FOREWORD ILCA's documentation and information retrieval services cater to the needs ofAfrican livestock researchers. -

EC MOZAMBIQUE JOINT ANNUAL REPORT on 2007

JAR 2007 - OPERATIONAL REVIEW 2008 EC ─ MOZAMBIQUE JOINT ANNUAL REPORT on 2007 For the Operational Review 2008 1 Chapter 1. Executive Summary The present document is the Joint Annual Report corresponding to implementation year 2007 that the Government of Mozambique and the European Commission have agreed on in 2008, as stipulated in the Cotonou Agreement, Annex IV, Article 5. This report analyses for the year the situation in the country; describes an overview of past and current EC cooperation in Mozambique; makes an assessment on policy coherence issues; identifies actions foreseen in the 10th EDF in accordance with the priority actions of EU- Africa Action Plan agreed in December 2007 and describes dialogue in the country with the NAO and the Non State Actors. It also presents an update of the existing general donor coordination and harmonization framework, and the main conclusions on the implementation of the 9th EDF CSP. The performance of the EC cooperation can be assessed in terms of financial absorption of the available envelope; sectoral and macro-economic performance in the sectors of intervention in relation to agreed targets aligned on the PARPA II objectives and quality of dialogue. In Mozambique for the period under consideration, those three elements can be considered as globally positive. However, improvements can be made in some specific areas. The evaluation of the current CSP (9th EDF) found that EC development cooperation in Mozambique is of high quality. The effectiveness of the EC Delegation as a partner of government supporting national poverty reduction policies has improved significantly during the period 2001-2007. -

Youth Programs

YOUTH PROGRAMS DINING CARD The Youth Programs Universal Dining Card is the perfect way to pre-pay your meals for great food at SEVERAL dining locations throughout Universal Orlando’s Theme Parks and Universal CityWalk™. QUICK SERVICE QUICK SERVICE LOCATIONS SAMPLE OPTIONS SAMPLE OPTIONS • Cheeseburger Combo served with • Bacon Cheeseburger Combo served fries and a small milkshake with fries and a small milkshake MEL’S DRIVE-IN • Grilled Chicken Sandwich Combo • Chicken Tenders Combo served served with fries and a small milkshake THE with fries and a small milkshake BURGER DIGS™ • Chicken Fingers Combo with cheese • Garden Burger Combo with cheese served with fries and a small milkshake served with fries and a small milkshake • Chicken Parmesan Combo served with spaghetti, a garlic breadstick and a side salad • Fried Chicken Combo served with mashed potatoes & gravy, corn on the cob and • Fettuccine Alfredo with Chicken Combo served LOUIE’S ITALIAN CIRCUS a side salad with a garlic breadstick and a side salad MCGURKUS CAFE RESTAURANT ™ • Chicken Sandwich served with fries and • Jumbo Slice Pizza Combo (Cheese, Pepperoni, STOO-PENDOUS a slice of apple pie Vegetable or Supreme) served with a garlic breadstick and a side salad • Chicken Caesar Salad • Fish & Chips • Toad in the Hole: popular dish of English • Fish & Chips sausage baked into a Yorkshire pudding • Chicken and Ribs Platter served with corn THREE LEAKY • Specialty Chicken Sandwich: grilled chicken ™ on the cob and roast potatoes ™ BROOMSTICKS CAULDRON breast, apple butter mayo, -

How It Works

The Universal Dining Plan offers you the utmost in savings and convenience. Now when you book your Universal Orlando® Resort vacation, you can purchase your meals and snacks in advance! Make the most of your time and enjoy family meals together at some of Universal Orlando’s most popular dining establishments. HOW IT WORKS Each day of the Universal Dining Plan entitles you to enjoy: • One TABLE SERVICE MEAL CONSIstING OF ONE EACH: When you purchase your vacation package and include the dining plan, you’ll receive a Entrée, chef-selected Dining Plan Dessert, & Non-Alcoholic Beverage ticket to be exchanged at Universal Orlando® Resort for a Universal Dining Plan card. • One quick SerVICE MEAL CONSIstING OF ONE EACH: You can pick up your Universal Dining Plan card at: Entrée & Non-Alcoholic Beverage • One SnaCK (such as a popcorn, ice cream, frozen beverage) • The Universal Ticket Center Desk at any Universal Orlando On-Site Hotel From food carts or quick service locations • The Dining Reservation Cart at either theme park or Universal CityWalk® • One BEVERAGE (non-alcoholic) • Guest Services at Universal Studios® or Universal’s Islands of Adventure® theme parks From food carts or quick service locations UNIVERSAL STUDIOS® UNIVERSAL’S ISLANDS OF ADVENTURE® UNIVERSAL CITYWALK® JUST LOOK FOR Lombard’s Seafood Grille L D Mythos Restaurant® L D Bob Marley - SM Finnegan’s Bar & Grill L D Confisco Grille® L D A Tribute to Freedom L D THIS SYMBOL ERVICE Jimmy Buffett’s S Margaritaville L D The Universal Dining Plan card is valid at OVER 100 dining locations throughout Red Oven Pizza Bakery℠ L D Universal Orlando’s theme parks and the Universal CityWalk® dining and ABLE T Antojitos Authentic Mexican Food D entertainment complex. -

DINNER MENU We Do Not Serve Fast Food

DINNER MENU We do not serve fast food. We serve good food as fast as we can. We make every plate to order. During busy times please have patience as your food may take a while to cook because we want it to be right. Grab a beverage, eat some chips and salsa and sit back and relax as we prepare your lunch, FARM FRESH SALADS brunch or dinner. Ole! Doug Allen, Owner Our delicious salads are made from hydroponic lettuce from locally owned Vet Veggies in Springdale. CHEESE CURDS Deep fried cheese STARTERS curds served with a side of our famous JOSE HOUSE SALAD Fresh and locally honey jalapeño mustard. $7.99 grown salad mix with tomatoes, green AVOCADO SALSA VERDE Our green onions, topped with guacamole and tomatillo and avocado salsa made WINGS Choose from boneless or bone- cheddar cheese. $9.49 fresh daily! $5.49 in. Jumbo wings drenched in delicious TACO SALAD Choose ground beef or FRESH GUACAMOLE Made fresh Hot Chipotle, Sweet BBQ sauce, Sweet Teriyaki or Mango Habanero. grilled chicken. Fresh and locally grown daily. $6.99 salad mix with tomatoes, black olives, ORIGINAL CON QUESO 8 oz. of the 6 wings $9.99, 10 wings $14.49. green onions, cheddar cheese and yellow stuff! $6.49 Add fresh cut fries $2.99 fresh guacamole. $10.49 QUESO BLANCO 8 oz. of the white TAMALES Our own homemade Pork FAJITA SALAD Grilled chicken or steak. stuff! $6.49 Tamales served steaming hot! Each Fresh and locally grown salad mix with $1.99, 1/2 Dozen $9.99, Dozen $14.99 bell peppers, caramelized onions, sour TRIPLE DIPPER Original queso, queso cream, fresh guacamole, pico de gallo, blanco and fresh guacamole. -

Fast Food and Childhood Obesity: Evidence from the UK

Fast Food and Childhood Obesity: Evidence from the UK Nicolás Libuy David Church George Ploubidis Emla Fitzsimons Excess weight in childhood and adolescence, by gender Girls Boys 0.4 0.4 0.35 0.35 0.3 0.3 0.25 0.25 0.2 0.2 0.15 0.15 0.1 0.1 0.05 0.05 0 0 age 3 age 5 age 7 age 11 age 14 age 3 age 5 age 7 age 11 age 14 Fast foods § Fast food outlets – incl. chip shops, burger bars and pizza places – account for more than a quarter (26%) of all eateries in England § 34% increase in fast food outlets from 2010 to 2018 in the UK § England’s poorest areas have 5 times more fast food outlets than the most affluent Research Question: does proximity to fast food restaurants affect childhood obesity rates? Challenge - associations between the two may reflect socioeconomic deprivation rather than the presence of fast food outlets Most papers based on cross-sectional data, or v local/small scale studies - must be interpreted cautiously … Research Question: does proximity to fast food restaurants affect childhood obesity rates? § Longitudinal, nationally representative data combined with highly granular geographic data provide unique opportunity to provide causal evidence for effective policy Data 1. Very detailed geo data on availability of fast food outlets across Great Britain: § OS ‘Points of Interest’ - 4 million+ commercial and public (non-residential) organisations - over 600 categories including fast food, supermarkets, green food stores etc. (2005 -) § OS ‘MasterMap’ - including road networks, building polygons, aerial photography and building heights (enabling 3D analysis) datasets (1997 -) 2. -

Mintel Reports Brochure

Burger and Chicken Restaurants - UK - September 2018 The above prices are correct at the time of publication, but are subject to Report Price: £1995.00 | $2693.85 | €2245.17 change due to currency fluctuations. “The biggest threat to the popularity of burger and chicken is the trend of consumers cutting back on eating meat. This is being driven by Younger Millennials who have either adopted a full-time vegan lifestyle or are simply eating more plant-based dishes. Operators now need to tackle this issue by offering consumers more varied choice, including vegan burgers.” – Trish Caddy, Foodservice Analyst This report looks at the following areas: BUY THIS • A meaty issue REPORT NOW • A sweet problem • Just how price-conscious are Millennials? VISIT: Much of the growth in the burger and chicken restaurants market has been driven by brands pushing store.mintel.com digital innovation and developing new takeaway and home delivery options. Meanwhile, sit-down restaurant chains have become destination businesses through offering healthier options, a higher quality of food, and a greater customer experience. CALL: EMEA The biggest threat to the popularity of burgers and chicken is the trend of consumers cutting back on +44 (0) 20 7606 4533 eating meat. Meanwhile, the frugal mentality continues to be deeply ingrained, which is likely to have some impact on discretionary spending on eating and drinking out-of-home. Brazil The forecast population growth of 5-14-year-olds over the next five years bodes well, given that 0800 095 9094 parents of under-16s are most likely to visit a burger or chicken outlet/restaurant on a regular basis. -

Exploring Customer Satisfaction with the Healthier Food Options Available at Fast-Food Outlets in South Africa

Exploring customer satisfaction with the healthier food options available at fast-food outlets in South Africa by Melanie Gopaul submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Master of Commerce in the subject of Business Management at the University of South Africa Supervisor: Prof. M.C. Cant Co-supervisor: Mr R. Machado December 2013 Student Number: 45366128 DECLARATION I declare that “Exploring customer satisfaction with the healthier food options available at fast-food outlets in South Africa”, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Commerce in the subject of Business Management with specialisation in Marketing at the University of South Africa (UNISA), is my own work and that all sources utilised within this research study have been acknowledged by means of complete references. ........................................................ Melanie Gopaul December 2013 - ii - DEDICATION To my parents, Sharen and Christopher Gopaul, who have always inspired and encouraged me to pursue my dreams – thank you for all the unconditional love, guidance and support that you have given me throughout my studies. - iii - ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to take this opportunity to express my sincere appreciation and gratitude to the following individuals who have been instrumental in the completion of this study: My supervisors, Prof. M.C. Cant and Mr R. Machado, for all their support, patience and excellent guidance. They have continuously encouraged and motivated me throughout this research study. Without them, this dissertation would not have been completed. I simply could not have wished for better supervisors. To my family, for always supporting and encouraging me with their best wishes. -

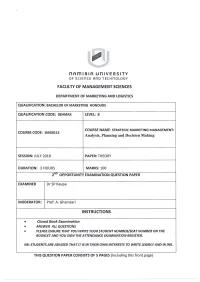

STRATEGIC MARKETING MANAGEMENT: COURSE CODE: Smg811ss Analysis, Planning and Decision Making

5 NAMIBIA UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY FACULTY OF MANAGEMENTSCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF MARKETING AND LOGISTICS QUALIFICATION: BACHELOR OF MARKETING HONOURS QUALIFICATION CODE: O8HMAR LEVEL: 8 COURSE NAME: STRATEGIC MARKETING MANAGEMENT: COURSE CODE: SMG811Ss Analysis, Planning and Decision Making SESSION: JULY 2018 PAPER: THEORY DURATION: 3 HOURS MARKS: 100 2™° OPPORTUNITY EXAMINATION QUESTION PAPER EXAMINER Dr SP Kaupa MODERATOR: Prof. A. Ghamsari INSTRUCTIONS ° Closed Book Examination e ANSWER ALL QUESTIONS e PLEASE ENSURE THAT YOU WRITE YOUR STUDENT NUMBER/SEAT NUMBERON THE BOOKLETAND YOU SIGN THE ATTENDANCE EXAMINATION REGISTER. NB: STUDENTS ARE ADVISED THATIT IS IN THEIR OWN INTERESTS TO WRITE LEGIBLY AND IN INK. THIS QUESTION PAPER CONSISTS OF 5 PAGES(Including this front page) READ THE ARTICLE BELOW AND ANSWERTHE QUESTIONS THAT FOLLOW: Real business madereal good - The story behind Steers Steers is one of the most well-known and successful quick-service restaurant brands in South Africa, with a noteworthy presence in a highly competitive fast food market. But where doestheir story begin? Their popularity and success centres on providing a range of flame grilled and value- for-money hamburgers to the consumer, while offering prospective franchisees the opportunity to be part of a lucrative franchise through its holding company, Famous Brands. Wheredoesthe story of Steers start? The history of the company revolves around the Halamandaris family, whose family members are still part of the executive team today, with extensive experience in the food and franchising industries. Steers founder, George Halamandaris had a vision to create a successful family run business and the idea for Steers originated while he was on holiday in the United States where he came across innovative food industry concepts and ideas. -

Recommendations and Conclusions from December 2019 Meeting

RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS CERF ADVISORY GROUP MEETING 5-6 DECEMBER 2019 1. The CERF Advisory Group was established by General Assembly resolution 60/124 to advise the Secretary-General, through the Under-Secretary-General (USG) for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator (ERC), on the use and impact of the fund. The second meeting of the Group in 2019 was held in New York on 5 and 6 December and was chaired by Alison Milton (Ireland). The ERC Mark Lowcock participated in two of the meeting sessions. 2. In the first session of the meeting, the Chair, the Director of the Humanitarian Financing and Resource Mobilization Division (HFRMD), Lisa Carty and the Chief of the Pooled Fund Management Branch (PFMB), Ms. Lisa Doughten welcomed five new members to the Group, including Abdul Hannan, Bangladesh, Honorary Advisor, All-Party Parliamentary Group of the Bangladesh National Parliament; Thomas Zahneisen, Germany, Director for Humanitarian Assistance, German Federal Foreign Office; Marriët Schuurman, Netherlands, Director of the Stabilisation and Humanitarian Aid Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands; Yngvild Berggrav, Norway, Policy Director, Section for Humanitarian Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Noralyn Jubaira-Baja, Philippines, Assistant Secretary, Office of United Nations and International Organizations, Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs; and Saud H. al- Shamsi, UAE, Deputy Permanent Representative, United Arab Emirates Mission to the United Nations and Amanda Magambo, Uganda, Head of Civilian Component Uganda Rapid Deployment Capability Centre (not present). The Chair presented the meeting agenda and summarized recommendations and conclusions from the Group’s meeting in June 2019. 3. The Chief of PFMB briefed on the use of the Fund during 2019.