Sarus Crane 'Triplets'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds of Bharatpur – Check List

BIRDS OF BHARATPUR – CHECK LIST Family PHASIANIDAE: Pheasants, Partridges, Quail Check List BLACK FRANCOLIN GREY FRANCOLIN COMMON QUAIL RAIN QUAIL JUNGLE BUSH QUAIL YELLOW-LEGGED BUTTON QUAIL BARRED BUTTON QUAIL PAINTED SPURFOWL INDIAN PEAFOWL Family ANATIDAE: Ducks, Geese, Swans GREATER WHITE-FRONTED GOOSE GREYLAG GOOSE BAR-HEADED GOOSE LWSSER WHISTLING-DUCK RUDDY SHELDUCK COMMON SHELDUCK COMB DUCK COTTON PYGMY GOOSE MARBLED DUCK GADWALL FALCATED DUCK EURASIAN WIGEON MALLARD SPOT-BILLED DUCK COMMON TEAL GARGANEY NORTHERN PINTAIL NORTHERN SHOVELER RED-CRESTED POCHARD COMMON POCHARD FERRUGINOUS POCHARD TUFTED DUCK BAIKAL TEAL GREATER SCAUP BAER’S POCHARD Family PICIDAE: Woodpeckers EURASIAN WRYNECK BROWN-CAPPED PYGMY WOODPECKER YELLOW-CROWNED WOODPECKER BLACK-RUMPED FLAMBACK Family CAPITONIDAE: Barbets BROWN-HEADED BARBET COPPERSMITH BARBET Family UPUPIDAE: Hoopoes COMMON HOOPOE Family BUCEROTIDAE: Hornbills INDAIN GREY HORNBILL Family CORACIIDAE: Rollers or Blue Jays EUROPEAN ROLLER INDIAN ROLLER Family ALCEDINIDAE: Kingfisher COMMON KINGFISHER STORK-BILLED KINGFISHER WHITE-THROATED KINGFISHER BLACK-CAPPED KINGFISHER PIED KINGFISHER Family MEROPIDAE: Bee-eaters GREEN BEE-EATER BLUE-CHEEKED BEE-EATER BLUE-TAILED BEE-EATER Family CUCULIDAE: Cuckoos, Crow-pheasants PIED CUCKOO CHESTNUT-WINGED CUCKOO COMMON HAWK CUCKOO INDIAN CUCKOO EURASIAN CUCKOO GREY-BELLIED CUCKOO PLAINTIVE CUCKOO DRONGO CUCKOO ASIAN KOEL SIRKEER MALKOHA GREATER COUCAL LESSER COUCAL Family PSITTACIDAS: Parrots ROSE-RINGED PARAKEET PLUM-HEADED PARKEET Family APODIDAE: -

Sustainable Conservation and Management of Indian Sarus Crane (Grus Antigone Antigone) in and Around Alwara Lake of District Kaushambi (U.P.), India

ISSN:150 2394-1391 Indian Journal of Biology Volume 5 Number 2, July - December 2018 Original Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21088/ijb.2394.1391.5218.7 Sustainable Conservation and Management of Indian Sarus crane (Grus antigone antigone) in and around Alwara Lake of District Kaushambi (U.P.), India Ashok Kumar Verma1, Shri Prakash2 Abstract The Indian Sarus crane, Grus antigone antigone is the only resident breeding crane of Indian subcontinent that has been declared as ‘State Bird’ by the Government of Uttar Pradesh. This is one of the most graceful, monogamous, non-migratory and tallest flying bird of the world that pair for lifelong and famous for marital fidelity. Population of this graceful bird now come in vulnerable situation due to the shrinking of wetlands at an alarming speed in the country. Present survey is aimed to study the population of sarus crane in the year 2017 in and around the Alwara Lake of district Kaushambi (Uttar Pradesh) India and their comparison to sarus crane population recorded from 2012 to 2016 in the same study area. This comparison reflects an increasing population trend of the said bird in the area studied. It has been observed that the prevailing ecological conditions of the lake, crane friendly behaviour of the local residents and awareness efforts of the authors have positive correlation in the sustainable conservation and increasing population trends of this vulnerable bird. Keywords: Alwara Lake; Conservation; Population Census; Sarus Crane; Increasing Trend. Introduction Author’s Affiliation: 1Head, Department of Zoology, Govt. P.G. College, Saidabad, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh 221508, India. -

Recommended Band Size List Page 1

Jun 00 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme - Recommended Band Size List Page 1 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme Recommended Band Size List - Birds of Australia and its Territories Number 24 - May 2000 This list contains all extant bird species which have been recorded for Australia and its Territories, including Antarctica, Norfolk Island, Christmas Island and Cocos and Keeling Islands, with their respective RAOU numbers and band sizes as recommended by the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme. The list is in two parts: Part 1 is in taxonomic order, based on information in "The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories" (1994) by Leslie Christidis and Walter E. Boles, RAOU Monograph 2, RAOU, Melbourne, for non-passerines; and “The Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines” (1999) by R. Schodde and I.J. Mason, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, for passerines. Part 2 is in alphabetic order of common names. The lists include sub-species where these are listed on the Census of Australian Vertebrate Species (CAVS version 8.1, 1994). CHOOSING THE CORRECT BAND Selecting the appropriate band to use combines several factors, including the species to be banded, variability within the species, growth characteristics of the species, and band design. The following list recommends band sizes and metals based on reports from banders, compiled over the life of the ABBBS. For most species, the recommended sizes have been used on substantial numbers of birds. For some species, relatively few individuals have been banded and the size is listed with a question mark. In still other species, too few birds have been banded to justify a size recommendation and none is made. -

Conservation Measures for the Siberian Crane

CMS Technical Series Publication No. 1 Conservation Measures for the Siberian Crane Convention on Migratory Species Published by: UNEP/CMS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany Recommended citation: UNEP/CMS. ed.(1999). Conservation Measures for the Siberian Crane. CMS Technical Series Publication No.1, UNEP/CMS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany. Cover photograph: Siberian Crane (Grus leucogeranus) in snow. © Sietre / BIOS, Paris © UNEP/CMS, 1999 (copyright of individual contributions remains with the authors). Reproduction of this publication, except the cover photograph, for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorized without permission from the copyright holder, provided the source is cited and the copyright holder receives a copy of the reproduced material. Reproduction of the text for resale or other commercial purposes, or of the cover photograph, is prohibited without prior permission of the copyright holder. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP/CMS, nor are they an official record. The designation of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP/CMS concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, nor concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries. Copies of this publication are available from the UNEP/CMS Secretariat, United Nations Premises in Bonn, Martin-Luther-King-Str. 8, D-53175 -

![Explorer Research Article [Tripathi Et Al., 6(3): March, 2015:4304-4316] CODEN (USA): IJPLCP ISSN: 0976-7126 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL of PHARMACY & LIFE SCIENCES (Int](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4638/explorer-research-article-tripathi-et-al-6-3-march-2015-4304-4316-coden-usa-ijplcp-issn-0976-7126-international-journal-of-pharmacy-life-sciences-int-1074638.webp)

Explorer Research Article [Tripathi Et Al., 6(3): March, 2015:4304-4316] CODEN (USA): IJPLCP ISSN: 0976-7126 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL of PHARMACY & LIFE SCIENCES (Int

Explorer Research Article [Tripathi et al., 6(3): March, 2015:4304-4316] CODEN (USA): IJPLCP ISSN: 0976-7126 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHARMACY & LIFE SCIENCES (Int. J. of Pharm. Life Sci.) Study on Bird Diversity of Chuhiya Forest, District Rewa, Madhya Pradesh, India Praneeta Tripathi1*, Amit Tiwari2, Shivesh Pratap Singh1 and Shirish Agnihotri3 1, Department of Zoology, Govt. P.G. College, Satna, (MP) - India 2, Department of Zoology, Govt. T.R.S. College, Rewa, (MP) - India 3, Research Officer, Fishermen Welfare and Fisheries Development Department, Bhopal, (MP) - India Abstract One hundred and twenty two species of birds belonging to 19 orders, 53 families and 101 genera were recorded at Chuhiya Forest, Rewa, Madhya Pradesh, India from all the three seasons. Out of these as per IUCN red list status 1 species is Critically Endangered, 3 each are Vulnerable and Near Threatened and rest are under Least concern category. Bird species, Gyps bengalensis, which is comes under Falconiformes order and Accipitridae family are critically endangered. The study area provide diverse habitat in the form of dense forest and agricultural land. Rose- ringed Parakeets, Alexandrine Parakeets, Common Babblers, Common Myna, Jungle Myna, Baya Weavers, House Sparrows, Paddyfield Pipit, White-throated Munia, White-bellied Drongo, House crows, Philippine Crows, Paddyfield Warbler etc. were prominent bird species of the study area, which are adapted to diversified habitat of Chuhiya Forest. Human impacts such as Installation of industrial units, cutting of trees, use of insecticides in agricultural practices are major threats to bird communities. Key-Words: Bird, Chuhiya Forest, IUCN, Endangered Introduction Birds (class-Aves) are feathered, winged, two-legged, Birds are ideal bio-indicators and useful models for warm-blooded, egg-laying vertebrates. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 74/Thursday, April 16, 2020/Notices

21262 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 74 / Thursday, April 16, 2020 / Notices acquisition were not included in the 5275 Leesburg Pike, Falls Church, VA Comment (1): We received one calculation for TDC, the TDC limit would not 22041–3803; (703) 358–2376. comment from the Western Energy have exceeded amongst other items. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Alliance, which requested that we Contact: Robert E. Mulderig, Deputy include European starling (Sturnus Assistant Secretary, Office of Public Housing What is the purpose of this notice? vulgaris) and house sparrow (Passer Investments, Office of Public and Indian Housing, Department of Housing and Urban The purpose of this notice is to domesticus) on the list of bird species Development, 451 Seventh Street SW, Room provide the public an updated list of not protected by the MBTA. 4130, Washington, DC 20410, telephone (202) ‘‘all nonnative, human-introduced bird Response: The draft list of nonnative, 402–4780. species to which the Migratory Bird human-introduced species was [FR Doc. 2020–08052 Filed 4–15–20; 8:45 am]‘ Treaty Act (16 U.S.C. 703 et seq.) does restricted to species belonging to biological families of migratory birds BILLING CODE 4210–67–P not apply,’’ as described in the MBTRA of 2004 (Division E, Title I, Sec. 143 of covered under any of the migratory bird the Consolidated Appropriations Act, treaties with Great Britain (for Canada), Mexico, Russia, or Japan. We excluded DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 2005; Pub. L. 108–447). The MBTRA states that ‘‘[a]s necessary, the Secretary species not occurring in biological Fish and Wildlife Service may update and publish the list of families included in the treaties from species exempted from protection of the the draft list. -

Sarus Crane Population Fluctuation at Various Wetlands at Bharatpur in Rajasthan State of India

Sarus Crane population fluctuation at various wetlands at Bharatpur in Rajasthan State of India Report submitted to the Society for Research in Ecology and Environment (SREE)as part of Interschool Education Programme on Wetland Conservation School Name: Rajkiya Upadhyay Varishtha Sanskrit Vidhyalaya and Rajkiya Uchcha Prathmik Vidhyalaya (City), Rajkiya Uchcha Prathmik Vidhyalaya Naveen City, Bharatpur School Guide: Shri Mukesh, Ms. Shashi Society Guide: Ms. Lata Verma and Dr. Ashok Verma Student Team: Puneet, Pankaj, Kunwar Singh, Shailaja Kumari, Priyanika, Ravi Sain, Anil, Radhakrishna, Mohit, Bhanu Sain, Shivam, Gaurav, Lokesh 2008 Contents Page Number Introduction 3 Study Area 5 Methodology 7 Results and discussion 8 Recommendations 13 References 15 ________________________________________________________________ Citation: SREE, 2008. Sarus Crane population fluctuation at various wetlands at Bharatpur in Rajasthan State of India. A Report submitted to Wetland Link International-Asia as part of Interschool Education Programme on Wetland Conservation. Pp. 10. 2 Sarus Crane (Grus antigone ) population fluctuation at various wetlands at Bharatpur in Rajasthan State of India INTRODUCTION There are six species of cranes found in India i.e. Common Crane Grus grus , Demoiselle Crane G. virgo , Siberian Crane G. leucogeranus , Hooded Crane G. monacha , Black-necked Crane G. nigricollis and Sarus Crane G. antigone . The first 4 cranes are long distance migratory birds probably coming from central asian breeding graounds. Of these, first three are winter visitors and fourth is vagrant to India. The Black-necked and Sarus Cranes are breeding cranes of India. The former is restricted to northern most part of India especially in Ladakh region while the latter is distributed widely in the country. -

Of Key Sites for the Siberian Crane and Other Waterbirds in Western/Central ASIA of Keysitesforthesiberian Crane Ndotherwterbirds in Western/Centralasi Atlas

A SI L A L A ATLAS OF KEY SITES FOR THE SIBERIAN CRANE AND OTHER WATERBIRDS IN WESTERN/CENTRAL ASIA TERBIRDS IN WESTERN/CENTR TERBIRDS IN A ND OTHER W ND OTHER A NE A N CR A IBERI S S OF KEY SITES FOR THE SITES FOR KEY S OF A ATL Citation: Ilyashenko, E.I., ed., 2010. Atlas of Key Sites for the Siberian Crane and Other Waterbirds in Western/Central Asia. International Crane Foundation, Baraboo, Wisconsin, USA. 116 p. Editor and compiler: Elena Ilyashenko Editorial Board: Crawford Prentice & Sara Gavney Moore Cartographers: Alexander Aleinikov, Mikhail Stishov English editor: Julie Oesper Layout: Elena Ilyashenko Atlas for the Siberian Crane and Other Waterbirds in Western/Central Asia ATLAS OF THE SIBERIAN CRANE SITES IN WESTERN/CENTRAL ASIA Elena I. Ilyashenko (editor) International Crane Foundation, Baraboo, Wisconsin, USA 2010 1 Atlas for the Siberian Crane and Other Waterbirds in Western/Central Asia Contents Foreword from the International Crane Foundation George Archibald ..................................... 3 Foreword from the Convention on Migratory Species Douglas Hykle........................................ 4 Introduction Elena Ilyashenko........................................................................................ 5 Western/Central Asian Flyway Breeding Grounds Russia....................................................................................................................... 9 Central Asian Flock 1. Kunovat Alexander Sorokin & Anastasia Shilina ............................................................. -

Conservation Status of Cranes

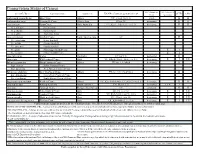

Conservation Status of Cranes IUCN Population ESA Endangered Scientific Name Common name Continent IUCN Red List Category & Criteria* CITES CMS Trend Species Act Anthropoides paradiseus Blue Crane Africa VU A2acde (ver 3.1) stable II II Anthropoides virgo Demoiselle Crane Africa, Asia LC(ver 3.1) increasing II II Grus antigone Sarus Crane Asia, Australia VU A2cde+3cde+4cde (ver 3.1) decreasing II II G. a. antigone Indian Sarus G. a. sharpii Eastern Sarus G. a. gillae Australian Sarus Grus canadensis Sandhill Crane North America, Asia LC II G. c. canadensis Lesser Sandhill G. c. tabida Greater Sandhill G. c. pratensis Florida Sandhill G. c. pulla Mississippi Sandhill Crane E I G. c. nesiotes Cuban Sandhill Crane E I Grus rubicunda Brolga Australia LC (ver 3.1) decreasing II Grus vipio White-naped Crane Asia VU A2bcde+3bcde+4bcde (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Balearica pavonina Black Crowned Crane Africa VU (ver 3.1) A4bcd decreasing II B. p. ceciliae Sudan Crowned Crane B. p. pavonina West African Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum Grey Crowned Crane Africa EN (ver. 3.1) A2acd+4acd decreasing II B. r. gibbericeps East African Crowned Crane B. r. regulorum South African Crowned Crane Bugeranus carunculatus Wattled Crane Africa VU A2acde+3cde+4acde; C1+2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing II II Grus americana Whooping Crane North America EN, D (ver 3.1) increasing E, EX I Grus grus Eurasian Crane Europe/Asia/Africa LC unknown II II Grus japonensis Red-crowned Crane Asia EN, C1 (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Grus monacha Hooded Crane Asia VU B2ab(I,ii,iii,iv,v); C1+2a(ii) decreasing E I I,II Grus nigricollis Black-necked Crane Asia VU C2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Leucogeranus leucogeranus Siberian Crane Asia CR A3bcd+4bcd (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Conservation status of species in the wild based on: The 2015 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, www.redlist.org CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) - A taxon is Critically Endangered when it is facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future. -

Balearica Pavonina L.) in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia

Scaling-up Public Education and Awareness Creations towards the Conservation of Black Crowned Crane (Balearica pavonina L.) in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia By: Dessalegn Obsi (Assistant Professor) June 8, 2017 Jimma University, Ethiopia Public capacity Building • There is ever increasing pressure on the world’s natural habitats which leads to species loss • Saving a species is not a quick or simple process - it may take several years or more of intensive management • Conservation is an interdisciplinary field and not just about the ecology that underpins our understanding of biodiversity The role of People in conservation People have different feelings about the importance of conservation b/c they value nature in d/t ways: Some people value nature for what it gives to them than in a material sense, like food, shelter, clean water and medicine which they need Others care more about less tangible things that nature provides for them , such as spiritual well-being or even a nice place to walk People may dislike some species or habitats b/c they see them as dangerous In need of protection • Species that are already threatened with extinction clearly are in more urgent need of protection than species that are still doing well. • To make decisions, conservationists first need to work out how threatened, or vulnerable, a species is. • On a global scale, the IUCN has produced the IUCN Red list1 which classifies species according to their current vulnerability to extinction. IUCN Red List Categories How does the IUCN Red List categories species by extinction risk? Species are assigned to Red List Categories based on: the rate of population decline, population size and structure, geographic range, habitat requirements and availability and threats. -

Near-Ultraviolet Light Reduced Sandhill Crane Collisions with a Power Line by 98% James F

AmericanOrnithology.org Volume XX, 2019, pp. 1–10 DOI: 10.1093/condor/duz008 RESEARCH ARTICLE Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/condor/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/condor/duz008/5476728 by University of Nebraska Kearney user on 09 May 2019 Near-ultraviolet light reduced Sandhill Crane collisions with a power line by 98% James F. Dwyer,*, Arun K. Pandey, Laura A. McHale, and Richard E. Harness EDM International, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA *Corresponding author: [email protected] Submission Date: 6 September, 2018; Editorial Acceptance Date: 25 February, 2019; Published May 6, 2019 ABSTRACT Midflight collisions with power lines impact 12 of the world’s 15 crane species, including 1 critically endangered spe- cies, 3 endangered species, and 5 vulnerable species. Power lines can be fitted with line markers to increase the visi- bility of wires to reduce collisions, but collisions can persist on marked power lines. For example, hundreds of Sandhill Cranes (Antigone canadensis) die annually in collisions with marked power lines at the Iain Nicolson Audubon Center at Rowe Sanctuary (Rowe), a major migratory stopover location near Gibbon, Nebraska. Mitigation success has been limited because most collisions occur nocturnally when line markers are least visible, even though roughly half the line markers present include glow-in-the-dark stickers. To evaluate an alternative mitigation strategy at Rowe, we used a randomized design to test collision mitigation effects of a pole-mounted near-ultraviolet light (UV-A; 380–395 nm) Avian Collision Avoidance System (ACAS) to illuminate a 258-m power line span crossing the Central Platte River. We observed 48 Sandhill Crane collisions and 217 dangerous flights of Sandhill Crane flocks during 19 nights when the ACAS was off, but just 1 collision and 39 dangerous flights during 19 nights when the ACAS was on. -

Cranes: Symbols of Survival 2013

Cranes: Symbols of Survival Ten-Year Strategic Vision for the International Crane Foundation Cranes are magnificent dancers, international travelers, and great ambassadors for conservation 2013 worldwide. What birds could be more deserving of our help and protection? Sir David Attenborough 1 Contents The International Crane Foundation . 5 Executive Summary . 6 Our Strategic Commitment . 7 The Essentials of Crane Conservation . 9 Our Mission Safeguarding Crane Populations . 10 The International Crane Foundation Securing Ecosystems, Watersheds, and Flyways . 14 works worldwide to conserve cranes and Bringing People Together . 16 the ecosystems, watersheds, and flyways on which they depend. ICF provides Improving Local Livelihoods . 18 knowledge, leadership, and inspiration to Empowering Conservation Leaders . 19 engage people in resolving threats to cranes Building Knowledge for Policy and Action . 20 and their diverse landscapes. Global Strategies for Our Future . 23 Water Security . 25 Our Vision Clean Energy . 26 The International Crane Foundation Land Stewardship . 27 commits to a future where all 15 of the Conservation on Agricultural Lands . 29 world’s crane species are secure. Through Climate Change Adaptation . 30 the charisma of cranes, people work Conservation-Friendly Livelihoods . 31 together to protect and restore wild crane populations and the landscapes they depend ICF Priority Programs . 33 on—and by doing so, find new pathways to sustain our water, land, and livelihoods. Sub-Saharan Africa . 34 East Asia . 37 South/Southeast Asia . 40 North America . 42 ICF Center for Conservation Leadership . 44 ICF: The Partner of Choice . 47 Cover: Black-necked Crane on Tibetan Plateau in China Photo by Carl-Albrecht von Treuenfels 3 The International Crane Foundation hen Ron Sauey and I met at Cornell University in 1971, we never imagined that our passion to create W a center to help cranes would evolve into what the International Crane Foundation (ICF) is today .