Design and Prototype of a Freshwater Ice Thickness Measuring Device

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numerical Modelling of Snow and Ice Thicknesses in Lake Vanajavesi, Finland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk SERIES A brought to you by CORE DYNAMIC METEOROLOGY provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto AND OCEANOGRAPHY PUBLISHED BY THE INTERNATIONAL METEOROLOGICAL INSTITUTE IN STOCKHOLM Numerical modelling of snow and ice thicknesses in Lake Vanajavesi, Finland By YU YANG1,2*, MATTI LEPPA¨ RANTA2 ,BINCHENG3,1 and ZHIJUN LI1, 1State Key Laboratory of Coastal and Offshore Engineering, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian 116024, China; 2Department of Physics, University of Helsinki, PO Box 48, FI-00014 Helsinki, Finland; 3Finnish Meteorological Institute, PO Box 503, FI-00101, Helsinki, Finland (Manuscript received 27 March 2011; in final form 7 January 2012) ABSTRACT Snow and ice thermodynamics was simulated applying a one-dimensional model for an individual ice season 2008Á2009 and for the climatological normal period 1971Á2000. Meteorological data were used as the model input. The novel model features were advanced treatment of superimposed ice and turbulent heat fluxes, coupling of snow and ice layers and snow modelled from precipitation. The simulated snow, snowÁice and ice thickness showed good agreement with observations for 2008Á2009. Modelled ice climatology was also reasonable, with 0.5 cm d1 growth in DecemberÁMarch and 2 cm d1 melting in April. Tuned heat flux from waterto ice was 0.5 W m 2. The diurnal weather cycle gave significant impact on ice thickness in spring. Ice climatology was highly sensitive to snow conditions. Surface temperature showed strong dependency on thickness of thin ice (B0.5 m), supporting the feasibility of thermal remote sensing and showing the importance of lake ice in numerical weather prediction. -

Cold Shock Response in Mammalian Cells

J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. (1999) 1(2): 243-255. Cold Shock ResponseJMMB in Mammalian Symposium Cells 243 Cold Shock Response in Mammalian Cells Jun Fujita* Less is known about the cold shock responses. In microorganisms, cold stress induces the synthesis of Department of Clinical Molecular Biology, several cold-shock proteins (Jones and Inouye, 1994). A Faculty of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan variety of plant genes are known to be induced by cold stress, and are thought to be involved in the stress tolerance of the plant (Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, 1996; Abstract Hughes et al., 1999). The response to cold stress in mammals, however, has attracted little attention except in Compared to bacteria and plants, the cold shock a few areas such as adaptive thermogenesis, cold response has attracted little attention in mammals tolerance, and storage of cells and organs. Recently, except in some areas such as adaptive thermogenesis, hypothermia is gaining popularity in emergency clinics as cold tolerance, storage of cells and organs, and a novel therapeutic modality for brain damages. In addition, recently, treatment of brain damage and protein low temperature cultivation has been dicussed as a method production. At the cellular level, some responses of to improve heterologous protein production in mammalian mammalian cells are similar to microorganisms; cold cells (Giard et al., 1982). stress changes the lipid composition of cellular Adaptive thermogenesis refers to a component of membranes, and suppresses the rate of protein energy expenditure, which is separable from physical synthesis and cell proliferation. Although previous activity. It can be elevated in response to changing studies have mostly dealt with temperatures below environmental conditions, most notably cold exposure and 20°C, mild hypothermia (32°C) can change the cell’s overfeeding. -

ADDENDUM SHEET America's Boating Course

ADDENDUM SHEET SM America’s Boating Course - 2001 Edition Homeland Security Measures Boaters must be aware of rules and guidelines regarding homeland security measures. The following are steps that boaters should take to protect our country and are a direct result of the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001. Keep your distance from all military vessels, cruise lines, or commercial shipping: • All vessels must proceed at a no-wake speed when within a Protection Zone (which extends 500 yards around U.S. naval vessels). • Non-military vessels are not allowed to enter within 100 yards of a U.S. naval vessel, whether underway or moored, unless authorized by an official patrol. The patrol may be either Coast Guard or Navy. • Violating the Naval Vessel Protection Zone is a felony offense, punishable by up to six years imprisonment and / or up to $250,000 in fines. Observe and avoid all security zones. Avoid commercial port operation areas. Avoid restricted areas near: • Dams • Naval ship yards • Power plants • Dry docks Do not stop or anchor beneath bridges or in channels. Keep your boat locked when not using it, including while at temporary docks, such as yacht clubs, restaurants, marinas, shopping, etc. When storing your boat disable the engine. If on a trailer, immobilize it so it cannot be moved. Keep a sharp eye out for anything that looks peculiar or out of the ordinary, and report it to the Coast Guard, port or marine security. When boating within a foreign country make certain that you check-in with the foreign country’s Customs Service upon entering the country and with the USA Customs Service and/or Immigration and Naturalization Service upon returning. -

Autonomic Conflict: a Different Way to Die During Cold Water Immersion

J Physiol 590.14 (2012) pp 3219–3230 3219 TOPICAL REVIEW ‘Autonomic conflict’: a different way to die during cold water immersion? Michael J. Shattock1 and Michael J. Tipton2 1Cardiovascular Division, King’s College London, London, UK 2Extreme Environments Laboratory, Department of Sports and Exercise Science, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK Abstract Cold water submersion can induce a high incidence of cardiac arrhythmias in healthy volunteers. Submersion and the release of breath holding can activate two powerful and antagonistic responses: the ‘cold shock response’ and the ‘diving response’.The former involves the activation of a sympathetically driven tachycardia while the latter promotes a parasympathetically mediated bradycardia. We propose that the strong and simultaneous activation of the two limbs of the autonomic nervous system (‘autonomic conflict’) may account for these arrhythmias and may, in some vulnerable individuals, be responsible for deaths that have previously wrongly been ascribed to drowning or hypothermia. In this review, we consider the evidence supporting this claim and also hypothesise that other environmental triggers may induce autonomic conflict and this may be more widely responsible for sudden death in individuals with other predisposing conditions. (Received 6 February 2012; accepted after revision 27 April 2012; first published online 30 April 2012) Corresponding author M. Shattock: Cardiovascular Division, King’s College London, The Rayne Institute, Lambeth Wing, St Thomas’ Hospital, London SE1 7EH, UK. Email: [email protected] Introduction: do all drowning victims drown? on average, we lose about one child a week. Historically, death in cold water was generally ascribed to hypothermia; In most countries of the world, immersion represents the more recently, description of the initial ‘cold shock’ second most common cause of accidental death in children response (Tipton, 1989b) to immersion and other factors and the third in adults (Bierens et al. -

2Growth, Structure and Properties of Sea

Growth, Structure and Properties 2 of Sea Ice Chris Petrich and Hajo Eicken 2.1 Introduction The substantial reduction in summer Arctic sea ice extent observed in 2007 and 2008 and its potential ecological and geopolitical impacts generated a lot of attention by the media and the general public. The remote-sensing data documenting such recent changes in ice coverage are collected at coarse spatial scales (Chapter 6) and typically cannot resolve details fi ner than about 10 km in lateral extent. However, many of the processes that make sea ice such an important aspect of the polar oceans occur at much smaller scales, ranging from the submillimetre to the metre scale. An understanding of how large-scale behaviour of sea ice monitored by satellite relates to and depends on the processes driving ice growth and decay requires an understanding of the evolution of ice structure and properties at these fi ner scales, and is the subject of this chapter. As demonstrated by many chapters in this book, the macroscopic properties of sea ice are often of most interest in studies of the interaction between sea ice and its environment. They are defi ned as the continuum properties averaged over a specifi c volume (Representative Elementary Volume) or mass of sea ice. The macroscopic properties are determined by the microscopic structure of the ice, i.e. the distribution, size and morphology of ice crystals and inclusions. The challenge is to see both the forest, i.e. the role of sea ice in the environment, and the trees, i.e. the way in which the constituents of sea ice control key properties and processes. -

Adaptation of the Cold Shock Response and Cooling Rates On

International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education Volume 9 | Number 2 Article 6 5-1-2015 Adaptation of the Cold Shock Response and Cooling Rates on Swimming Following Repeated Cold Water Immersions in a Group of Children Aged 10 – 12 years Flora Bird Queen's Hospital, [email protected] Jim House University of Portsmouth Michael J. Tipton University of Portsmouth Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ijare Recommended Citation Bird, Flora; House, Jim; and Tipton, Michael J. (2015) "Adaptation of the Cold Shock Response and Cooling Rates on Swimming Following Repeated Cold Water Immersions in a Group of Children Aged 10 – 12 years," International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education: Vol. 9: No. 2, Article 6. Available at: http://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ijare/vol9/iss2/6 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Bird et al.: Adaptation of the Cold Shock Response and Cooling Rates on Swimmi International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, 2015, 9, 149 -161 http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/ijare.2014-0081 © 2015 Human Kinetics, Inc. ORIGINAL RESEARCH Adaptation of the Cold Shock Response and Cooling Rates on Swimming Following Repeated Cold Water Immersions in a Group of Children Aged 10–12 Years Flora Bird Queen’s Hospital James R. House and Michael J. Tipton University of Portsmouth Habituation of the cold shock response and adaptation in deep body cooling with prolonged cold water immersion is well documented in adults. -

Chronology, Stable Isotopes, and Glaciochemistry of Perennial Ice in Strickler Cavern, Idaho, USA

Investigation of perennial ice in Strickler Cavern, Idaho, USA Chronology, stable isotopes, and glaciochemistry of perennial ice in Strickler Cavern, Idaho, USA Jeffrey S. Munroe†, Samuel S. O’Keefe, and Andrew L. Gorin Geology Department, Middlebury College, Middlebury, Vermont 05753, USA ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION in successive layers of cave ice can provide a record of past changes in atmospheric circula- Cave ice is an understudied component The past several decades have witnessed a tion (Kern et al., 2011a). Alternating intervals of of the cryosphere that offers potentially sig- massive increase in research attention focused ice accumulation and ablation provide evidence nificant paleoclimate information for mid- on the cryosphere. Work that began in Antarc- of fluctuations in winter snowfall and summer latitude locations. This study investigated tica during the first International Geophysi- temperature over time (e.g., Luetscher et al., a recently discovered cave ice deposit in cal Year in the late 1950s (e.g., Summerhayes, 2005; Stoffel et al., 2009), and changes in cave Strickler Cavern, located in the Lost River 2008), increasingly collaborative efforts to ex- ice mass balances observed through long-term Range of Idaho, United States. Field and tract long ice cores from Antarctica (e.g., Jouzel monitoring have been linked to weather patterns laboratory analyses were combined to de- et al., 2007; Petit et al., 1999) and Greenland (Schöner et al., 2011; Colucci et al., 2016). Pol- termine the origin of the ice, to limit its age, (e.g., Grootes et al., 1993), satellite-based moni- len and other botanical evidence incorporated in to measure and interpret the stable isotope toring of glaciers (e.g., Wahr et al., 2000) and the ice can provide information about changes compositions (O and H) of the ice, and to sea-ice extent (e.g., Serreze et al., 2007), field in surface environments (Feurdean et al., 2011). -

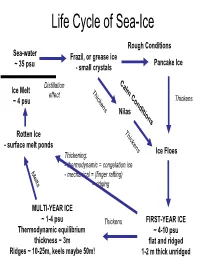

Life Cycle of Sea-Ice

Life Cycle of Sea-Ice Rough Conditions Sea-water Frazil, or grease ice Pancake Ice ~ 35 psu - small crystals C Distillation a Ice Melt T lm effect hi C ~ 4 psu ck o Thickens ens nd Nilas itio ns T hi Rotten Ice c - surface melt ponds kens Ice Floes Thickening: - thermodynamic = congelation ice M e - mechanical = (finger rafting) l ts = ridging MULTI-YEAR ICE ~ 1-4 psu Thickens FIRST-YEAR ICE Thermodynamic equilibrium ~ 4-10 psu thickness ~ 3m flat and ridged Ridges ~ 10-25m, keels maybe 50m! 1-2 m thick unridged Internal Structure of Sea Ice Brine Channels within the ice (~width of human hair) Brine rejected from ice (4-10psu), away from surface, but concentrates in brine channels long crystals as congelation ice (small volume but VERY HIGH SALINITIES) (frozen on from below) -6 deg C -10 deg C -21 deg C 100psu 145psu 216psu Pictures from AWI Brine Volume and Salinity From Thomas and Dieckmann 2002, Science .... adapted from papers by Hajo Eichen Impacts of Sea-ice on the Ocean ICE FORMATION and PRESENCE Wind - brine rejection - Ocean-Atmos momentum barrier - Ocean-Atmos heat barrier - ice edge processes (e.g. upwelling) - keel stirring (i.e. mixing, but < wind) Ocean 10psu MELTING ICE Fresh 35psu - stratification (fresher water) (cf. distillation as ice moves from formation region) Saltier - transport of sediment, etc S increases START FREEZE MELT Impacts of Sea-ice on the Atmosphere ICE PRESENCE - albedo change - Ocean-Atmos momentum barrier - Ocean-Atmos heat barrier Water Sky Sea Smoke Heat balance S=Shortwave radiation from sun (reflects off clouds and surface) albedo= how much radiation reflects from surface albedo of ice ~ 0.8 albedo of water ~ 0.04 (if sun overhead) L=Longwave radiation (from surface and clouds) F=Heat flux from Ocean M=Melt (snow and ice) From N. -

Frazil Ice Formation in the Polar Oceans

Frazil Ice Formation in the Polar Oceans Nikhil Vibhakar Radia Department of Earth Sciences, UCL A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: D. L. Feltham August, 2013 1 I, Nikhil Vibhakar Radia, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. SIGNED 2 Abstract Areas of open ocean within the sea ice cover, known as leads and polynyas, expose ocean water directly to the cold atmosphere. In winter, these are regions of high sea ice production, and they play an important role in the mass balance of sea ice and the salt budget of the ocean. Sea ice formation is a complex process that starts with frazil ice crys- tal formation in supercooled waters, which grow and precipitate to the ocean surface to form grease ice, which eventually consolidates and turns into a layer of solid sea ice. This thesis looks at all three phases, concentrating on the first. Frazil ice comprises millimetre- sized crystals of ice that form in supercooled, turbulent water. They initially form through a process of seeding, and then grow and multiply through secondary nucleation, which is where smaller crystals break off from larger ones to create new nucleii for further growth. The increase in volume of frazil ice will continue to occur until there is no longer super- cooling in the water. The crystals eventually precipitate to the surface and pile up to form grease ice. The presence of grease ice at the ocean surface dampens the effects of waves and turbulence, which allows them to consolidate into a solid layer of ice. -

A Quantitative Proteomics Investigation of Cold Adaptation in the Marine Bacterium, Sphingopyxis Alaskensis

A quantitative proteomics investigation of cold adaptation in the marine bacterium, Sphingopyxis alaskensis Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) Lily L. J. Ting School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences University of New South Wales January 2010 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ‘I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). I have either used no substantial portions of copyright material in my thesis or I have obtained permission to use copyright material; where permission has not been granted I have applied/will apply for a partial restriction of the digital copy of my thesis or dissertation.' Signed ……………………………………………........................... 21st April, 2010 Date ……………………………………………........................... AUTHENTICITY STATEMENT ‘I certify that the Library deposit digital copy is a direct equivalent of the final officially approved version of my thesis. No emendation of content has occurred and if there are any minor variations in formatting, they are the result of the conversion to digital format.’ Signed ……………………………………………........................... 21st April, 2010 Date …………………………………………….......................... -

Anchor Ice and Bottom-Freezing in High-Latitude Marine Sedimentary Environments: Observations from the Alaskan Beaufort Sea

ANCHOR ICE AND BOTTOM-FREEZING IN HIGH-LATITUDE MARINE SEDIMENTARY ENVIRONMENTS: OBSERVATIONS FROM THE ALASKAN BEAUFORT SEA by Erk Reimnitz, E. W. Kempema, and P. W. Barnes U.S. Geological Survey Menlo Park, California 94025 Final Report Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program Research Unit 205 1986 257 This report has also been published as U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 86-298. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study was funded in part by the Minerals Management Service, Department of the Interior, through interagency agreement with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Department of Commerce, as part of the Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program. We thank D. A. Cacchione for his thoughtful review of the manuscript. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . ...259 INTRODUCTION . 263 REGIONAL SETTING . ...264 INDIRECT EVIDENCE FOR ANCHOR ICE IN THE BEAUFORT SEA . ...266 DIVER OBSERVATIONS OF ANCHOR ICE AND ICE-BONDED SEDIMENTS . ...271 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION . ...274 REFERENCES CITED . ...278 INTRODUCTION As early as 1705 sailors observed that rivers sometimes begin to freeze from the bottom (Barnes, 1928; Piotrovich, 1956). Anchor ice has been observed also in lakes and the sea (Zubov, 1945; Dayton, et al., 1969; Foulds and Wigle, 1977; Martin, 1981; Tsang, 1982). The growth of anchor ice implies interactions between ice and the sub- strate, and a marked change in the sedimentary environment. However, while the literature contains numerous observations that imply sediment transport, no studies have been conducted on the effects of anchor ice growth on sediment dynamics and bedforms. Underwater ice is the general term for ice formed in the supercooled water column. -

Optical Properties of the Ice Cover on Vendyurskoe Lake, Russian Karelia (1995–2012)

Annals of Glaciology 54(62) 2013 doi: 10.3189/2013AoG62A179 121 Optical properties of the ice cover on Vendyurskoe lake, Russian Karelia (1995–2012) G. ZDOROVENNOVA, R. ZDOROVENNOV, N. PALSHIN, A. TERZHEVIK Northern Water Problems Institute, Karelian Scientific Centre, Russian Academy of Sciences, Petrozavodsk, Russia E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Solar radiation penetrating the ice is one of the most important factors that determine the functioning of lake ecosystem in late winter. Parameterization of the attenuation of solar radiation in the snow-ice sheet is an essential tool in the study of the light regime of ice-covered lakes. The optical properties of the snow-ice sheet in Vendyurskoe lake, northwestern Russia, are investigated on the basis of long-term field observations (1995–2012). The four-layer approach (snow, white ice, slush and congelation ice) is used to study the attenuation of the downwelling planar irradiance in the snow-ice sheet. The bulk attenuation coefficients for four layers (18.8 m–1 for snow, 6 m–1 for white ice, 3.5 m–1 for slush and 2.1 m–1 for congelation ice) are calculated by the quasi-Newton method. A comparison of observed and calculated values of the irradiance beneath the ice shows that the determined coefficients adequately describe the attenuation of the downwelling irradiance by snow-ice cover. INTRODUCTION during intense melting have been studied insufficiently Ice and snow cover not only prevents gas exchange, but also because of the difficulty of carrying out in situ measurements insulates water bodies from the thermodynamic effect of the on weakened ice.