The Definition and Practice of Ecclesiastical Oikonomia in Byzantium During the 7Th and 8Th Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TO the HISTORICAL RECEPTION of AUGUSTINE Volume 3

THE OXFORD GUIDE TO THE HISTORICAL RECEPTION OF AUGUSTINE Volume 3 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: KARLA POLLMANN EDITOR: WILLEMIEN OTTEN CO-EDITORS: JAM ES A. ANDREWS, A I. F. X ANDER ARWE ILER, IRENA BACKUS, S l LKE-PETRA BERGJAN, JOHANN ES BRACHTENDORF, SUSAN N EL KHOLI, MARK W. ELLIOTT, SUSANNE GAT ZEME I ER, PAUL VAN GEEST, BRUCE GORDON, DAVID LAMBERT, PETERLlEB REGTS, HILDEGUND MULLER, HI LMAR PABEL,JEAN-LOUlS QUANTlN, ER IC L. SAAK, LYDIA SC H UMACHER, ARNOUD VISSER, KONRAD VOSS l NG, J ACK ZUPKO. OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1478 I ORTHODOX CHURCH (SINCE 1453) --, Et~twickltmgsgesdLiclite des Erbsiit~dendogmas seit da Rejomw Augustiniana. Studien uber Augustin us Lmd .<eille Rezeption. Festgabefor tiall, Geschichtc des Erbsundendogmas. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte Willigis Eckermmm OSA Z llll l 6o. Geburtstag (Wiirzburg 1994) des Problems vom Ursprung des Obels 4 (Munich 1972 ). 25<,> - 90. P. Guilluy, 'Peche originel', Ca tl~al icis m e 10 (1985) 1036-61. R. Schwager, Erbsu11de und Heilsd,·ama im Kontcxt von Evolution, P. Henrici, '1l1e Philosophers and Original Sin', Conm1Unio 18 (•99•) Gcntechnology zmd Apokalyptik (Miinster 1997 ). 489-901. M. Stickelbroeck, U.-s tand, Fall 1md HrbsLinde. ln der nacilaugusti M. Huftier, 'Libre arbitrc, liberte et peche chez saint Augustin', nischen Ara bis zum Begimz der Sclwlastik. Die lateinische Theologie, Recherches de tlu!ologie a11 ciwne et medievale 33 (1966) 187-281. Handbuch der Dogmengeschichte 2/3a, pt 3 (Freiburg 2007 ) . M. F. johnson, 'Augustine and Aquinas on Original Sin; in B. D. Dau C. Straw, 'Gregory I; in A. D. Fitzgerald (ed.), Augusti11e through the phinais, B. -

The Revelation of God, East and West: Contrasting Special Revelation in Western Modernity with the Ancient Christian East

Open Theology 2017; 3: 565–589 Analytic Perspectives on Method and Authority in Theology Nathan A. Jacobs* The Revelation of God, East and West: Contrasting Special Revelation in Western Modernity with the Ancient Christian East https://doi.org/10.1515/opth-2017-0043 Received August 11, 2017; accepted September 11, 2017 Abstract: The questions of whether God reveals himself; if so, how we can know a purported revelation is authentic; and how such revelations relate to the insights of reason are discussed by John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, G. W. Leibniz, and Immanuel Kant, to name a few. Yet, what these philosophers say with such consistency about revelation stands in stark contrast with the claims of the Christian East, which are equally consistent from the second century through the fourteenth century. In this essay, I will compare the modern discussion of special revelation from Thomas Hobbes through Johann Fichte with the Eastern Christian discussion from Irenaeus through Gregory Palamas. As we will see, there are noteworthy differences between the two trajectories, differences I will suggest merit careful consideration from philosophers of religion. Keywords: Religious Epistemology; Revelation; Divine Vision; Theosis; Eastern Orthodox; Locke; Hobbes; Lessing; Kant; Fichte; Irenaeus; Cappadocians; Cyril of Alexandria; Gregory Palamas The idea that God speaks to humanity, revealing things hidden or making his will known, comes under careful scrutiny in modern philosophy. The questions of whether God does reveal himself; if so, how we can know a purported revelation is authentic; and how such revelations relate to the insights of reason are discussed by John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, G. -

Logos-Sarx Christology and the Sixth-Century Miaenergism

VOX PATRUM 37 (2017) t. 67 Oleksandr KASHCHUK* LOGOS-SARX CHRISTOLOGY AND THE SIXTH-CENTURY MIAENERGISM From the early years of Christian theology to the Council of Ephesus (431) the main task for Christology was to affirm the reality of both divinity and humanity in the person of Christ. Each of the great theological centers, such as Antioch and Alexandria, was to emphasize a different aspect of Christology in defense of orthodoxy. After the Council of Nicaea (325) the adherents of consubstantial (ÐmooÚsioj) saw difficulty in defining the reality of Christ’s humanity. This question arose in the period between Nicaea and Ephesus (325- 431). Bishops and theologians stressed the unity of subject of Christ and the truth of his humanity. Although during the time from Ephesus to Chalcedon (431-451) the fullness of divinity and humanity were acknowledged by majo- rity, there arose the debate concerning the relationship between the human and divine elements within Christ on the one hand and relationship between these elements on the other. The debate passed into the question concerning the ex- pression of Christ’s two natures coexisting in one person. So the main focus of the Christological discussion in the sixth century shifted from the problem of unity and interrelation between elements in Christ to the expression of unity through activity and its consequences for the fullness of Christ’s humanity. The issue of Christ’s operation and will thus became the most prevalent ques- tions in Christology from the late sixth to the early seventh centuries. At that time there arose the Miaenergist debate concerning whether Christ had a whol- ly human as well as a wholly divine operation and volition. -

2. the Sacrament of Marriage and Its Impediments

THE SACRAMENT OF MARRIAGE AND ITS IMPEDIMENTS I. On Orthodox Marriage 1. The institution of the family is threatened today by such phenomena as secularization and moral relativism. The Orthodox Church maintains, as her fundamental and indisputable teaching, that marriage is sacred. The freely entered union of man and woman is an indispensable precondition for marriage. 2. In the Orthodox Church, marriage is considered to be the oldest institution of divine law because it was instituted simultaneously with the creation of Adam and Eve, the first human beings (Gen 2:23). Since its origin, this union not only implies the spiritual communion of a married couple—a man and a woman—but also assured the continuation of the human race. As such, the marriage of man and woman, which was blessed in Paradise, became a holy mystery, as mentioned in the New Testament where Christ performs His first sign, turning water into wine at the wedding in Cana of Galilee, and thus reveals His glory (Jn 2:11). The mystery of the indissoluble union between man and woman is an icon of the unity of Christ and the Church (Eph 5:32). 3. Thus, the Christocentric typology of the sacrament of marriage explains why a bishop or a presbyter blesses this sacred union with a special prayer. In his letter to Polycarp of Smyrna, Ignatius the God-Bearer stressed that those who enter into the communion of marriage must also have the bishop’s approval, so that their marriage may be according to God, and not after their own desire. -

Appendix I: an Extended Critique of Ecumenist Reasoning

This is a chapter from The Non-Orthodox: The Orthodox Teaching on Christians Outside of the Church. This book was originally published in 1999 by Regina Orthodox Press in Salisbury, MA (Frank Schaeffer’s publishing house). For the complete book, as well as reviews and related articles, go to http://orthodoxinfo.com/inquirers/status.aspx. (© Patrick Barnes, 1999, 2004) Appendix I: An Extended Critique of Ecumenist Reasoning Preliminary Remarks Before beginning our analysis, a few words need to be said about the term “ecumenist.” First, we Orthodox opposed to the more aberrant forms of ecumenism are not against ecumenism in its true and proper form—i.e., activities proper to the Apostolic mark of the Church (to be “sent out”), conducted in ways that do not violate Orthodox canonical guidelines. “Ecumenist” and “ecumenism” carry both positive and negative connotations which should be respectively qualified by words such as “true“ or “political“. In this book “ecumenist” is employed in its negative connotation, referring to a person “infected“ with what the Holy Fathers call the bacterium of an ecclesiological heresy. The chief symptoms of this disease are statements and activities that contradict or compromise the unity and uniqueness of the Church, and which expand Her boundaries in ways that are foreign to Her self-understanding. At an advanced stage, these symptoms often include an open espousal of various forms of the heretical Branch Theory of the Church, accompanied by an open disdain for those Faithful who stand opposed to the erosion of Holy Tradition and the Patristic mindset which so often characterizes Orthodox involvement in the ecumenical movement. -

A Study on Religious Variables Influencing GDP Growth Over Countries

Religion and Economic Development - A study on Religious variables influencing GDP growth over countries Wonsub Eum * University of California, Berkeley Thesis Advisor: Professor Jeremy Magruder April 29, 2011 * I would like to thank Professor Jeremy Magruder for his valuable advice and guidance throughout the paper. I would also like to thank Professor Roger Craine, Professor Sofia Villas-Boas, and Professor Minjung Park for their advice on this research. Any error or mistake is my own. Abstract Religion is a popular topic to be considered as one of the major factors that affect people’s lifestyles. However, religion is one of the social factors that most economists are very careful in stating a connection with economic variables. Among few researchers who are keen to find how religions influence the economic growth, Barro had several publications with individual religious activities or beliefs and Montalvo and Reynal-Querol on religious diversity. In this paper, I challenge their studies by using more recent data, and test whether their arguments hold still for different data over time. In the first part of the paper, I first write down a simple macroeconomics equation from Mankiw, Romer, and Weil (1992) that explains GDP growth with several classical variables. I test Montalvo and Reynal-Querol (2003)’s variables – religious fragmentation and religious polarization – and look at them in their continents. Also, I test whether monthly attendance, beliefs in hell/heaven influence GDP growth, which Barro and McCleary (2003) used. My results demonstrate that the results from Barro’s paper that show a significant correlation between economic growth and religious activities or beliefs may not hold constant for different time period. -

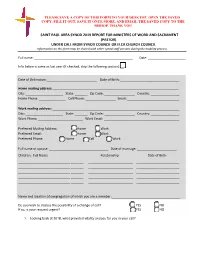

UNDER CALL from SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on This Form May Be Shared with Other Synod Staff Persons During the Mobility Process

PLEASE SAVE A COPY OF THIS FORM TO YOUR DESKTOP, OPEN THE SAVED COPY, FILL IT OUT, SAVE IT ONCE MORE, AND EMAIL THE SAVED COPY TO THE BISHOP. THANK YOU SAINT PAUL AREA SYNOD 2019 REPORT FOR MINISTERS OF WORD AND SACRAMENT (PASTOR) UNDER CALL FROM SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on this form may be shared with other synod staff persons during the mobility process Full name: _______________________________________________________ Date: _____________________ Info below is same as last year (if checked, skip the following section):__ Date of Ordination:____________________________ Date of Birth: _________________________________ Home mailing address: ______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Home Phone: _______________ Cell Phone: _________________ Email: _____________________________ Work mailing address: _______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Work Phone: _________________________ Work Email: __________________________________________ Preferred Mailing Address: Home Work Preferred Email: Home Work Preferred Phone: Home Cell Work Full name of spouse: _________________________________ Date of marriage: ______________________ Children: Full Name Relationship Date of Birth _____________________________ _______ _________________________ ________________________ _____________________________ -

The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene : Philosophical Terminology and Theological Arguments

Durham E-Theses The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene : philosophical terminology and theological arguments Metallidis, George How to cite: Metallidis, George (2003) The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene : philosophical terminology and theological arguments, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1085/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM DEPARTMENT OF THEOLOGY GEORGE METALLIDIS The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consentand information derived from it should be acknowledged. The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene: Philosophical Terminology and Theological Arguments PhD Thesis/FourthYear Supervisor: Prof. ANDREW LOUTH 0-I OCT2003 Durham 2003 The ChalcedonianChristology of St John Damascene To my Mother Despoina The ChalcedonianChristology of St John Damascene CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENT 12 INTRODUCTION 14 CHAPTER ONE TheLife of St John Damascene 1. -

Embracing Icons: the Face of Jacob on the Throne of God*

Images 2007_f13_36-54 8/13/07 5:19 PM Page 36 RACHEL NEIS University of Michigan EMBRACING ICONS: THE FACE OF JACOB ON THE THRONE OF GOD* Abstract I bend over it, embrace, kiss and fondle to it, Rachel Neis’ article treats Hekhalot Rabbati, a collection of early and my hands are upon its arms, Jewish mystical traditions, and more specifically §§ 152–169, a three times, when you speak before me “holy.” series of Qedusha hymns. These hymns are liturgical performances, As it is said: holy, holy, holy.1 the highlight of which is God’s passionate embrace of the Jacob icon Heikhalot Rabbati, § 164 on his throne as triggered by Israel’s utterance of the Qedusha. §§ 152–169 also set forth an ocular choreography such that the For over a century, scholars conceived of the relation- gazes of Israel and God are exchanged during the recitation of the ship between visuality in Judaism and Christianity Qedusha. The article set these traditions within the history of sim- in binary terms.2 Judaism was understood as a reli- ilar Jewish traditions preserved in Rabbinic literature. It will be argued that §§ 152–169 date to the early Byzantine period, reflecting gion of the word in opposition to Christianity, a Jewish interest in images of the sacred parallel to the contempo- which was seen as a deeply visual culture. For raneous Christian intensification of the cult of images and preoccupation many scholars, never the twain did meet—Jews with the nature of religious images. were always “the nation without art,” or “artless,”3 while for much of their history Christians embraced Bear witness to them 4 5 of what testimony you see of me, icons, creating visual representations of the divine. -

The Transfiguration in the Theology of Gregory Palamas And

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 2015 Deus in se et Deus pro nobis: The rT ansfiguration in the Theology of Gregory Palamas and Its Importance for Catholic Theology Cory Hayes Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Hayes, C. (2015). Deus in se et Deus pro nobis: The rT ansfiguration in the Theology of Gregory Palamas and Its Importance for Catholic Theology (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/640 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEUS IN SE ET DEUS PRO NOBIS: THE TRANSFIGURATION IN THE THEOLOGY OF GREGORY PALAMAS AND ITS IMPORTANCE FOR CATHOLIC THEOLOGY A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Cory J. Hayes May 2015 Copyright by Cory J. Hayes 2015 DEUS IN SE ET DEUS PRO NOBIS: THE TRANSFIGURATION IN THE THEOLOGY OF GREGORY PALAMAS AND ITS IMPORTANCE FOR CATHOLIC THEOLOGY By Cory J. Hayes Approved March 31, 2015 _______________________________ ______________________________ Dr. Bogdan Bucur Dr. Radu Bordeianu Associate Professor of Theology Associate Professor of Theology (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) _______________________________ Dr. Christiaan Kappes Professor of Liturgy and Patristics Saints Cyril and Methodius Byzantine Catholic Seminary (Committee Member) ________________________________ ______________________________ Dr. James Swindal Dr. -

Saint Maximus the Confessor and His Defense of Papal Primacy

Love that unites and vanishes: Saint Maximus the Confessor and his defense of papal primacy Author: Jason C. LaLonde Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:108614 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2019 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Love that Unites and Vanishes: Saint Maximus the Confessor and his Defense of Papal Primacy Thesis for the Completion of the Licentiate in Sacred Theology Boston College School of Theology and Ministry Fr. Jason C. LaLonde, S.J. Readers: Fr. Brian Dunkle, S.J., BC-STM Dr. Adrian Walker, Catholic University of America May 3, 2019 2 Introduction 3 Chapter One: Maximus’s Palestinian Provenance: Overcoming the Myth of the Greek Life 10 Chapter Two: From Monoenergism to Monotheletism: The Role of Honorius 32 Chapter Three: Maximus on Roman Primacy and his Defense of Honorius 48 Conclusion 80 Appendix – Translation of Opusculum 20 85 Bibliography 100 3 Introduction The current research project stems from my work in the course “Latin West, Greek East,” taught by Fr. Brian Dunkle, S.J., at the Boston College School of Theology and Ministry in the fall semester of 2016. For that course, I translated a letter of Saint Maximus the Confessor (580- 662) that is found among his works known collectively as the Opuscula theologica et polemica.1 My immediate interest in the text was Maximus’s treatment of the twin heresies of monoenergism and monotheletism. As I made progress -

The Development of Marian Doctrine As

INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON, OHIO in affiliation with the PONTIFICAL THEOLOGICAL FACULTY MARIANUM ROME, ITALY By: Elizabeth Marie Farley The Development of Marian Doctrine as Reflected in the Commentaries on the Wedding at Cana (John 2:1-5) by the Latin Fathers and Pastoral Theologians of the Church From the Fourth to the Seventeenth Century A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate in Sacred Theology with specialization in Marian Studies Director: Rev. Bertrand Buby, S.M. Marian Library/International Marian Research Institute University of Dayton 300 College Park Dayton, OH 45469-1390 2013 i Copyright © 2013 by Elizabeth M. Farley All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Nihil obstat: François Rossier, S.M., STD Vidimus et approbamus: Bertrand A. Buby S.M., STD – Director François Rossier, S.M., STD – Examinator Johann G. Roten S.M., PhD, STD – Examinator Thomas A. Thompson S.M., PhD – Examinator Elio M. Peretto, O.S.M. – Revisor Aristide M. Serra, O.S.M. – Revisor Daytonesis (USA), ex aedibus International Marian Research Institute, et Romae, ex aedibus Pontificiae Facultatis Theologicae Marianum, die 22 Augusti 2013. ii Dedication This Dissertation is Dedicated to: Father Bertrand Buby, S.M., The Faculty and Staff at The International Marian Research Institute, Father Jerome Young, O.S.B., Father Rory Pitstick, Joseph Sprug, Jerome Farley, my beloved husband, and All my family and friends iii Table of Contents Prėcis.................................................................................. xvii Guidelines........................................................................... xxiii Abbreviations...................................................................... xxv Chapter One: Purpose, Scope, Structure and Method 1.1 Introduction...................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose............................................................