The Films of Julian Schnabel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joan Quinn Captured

Opening ReceptiOn: june 28, 7pm–10pm AdmissiOn is fRee Joan Quinn Captured Curated by Laura Whitcomb and organized by Brand Library Art Galleries panel discussions, talks and film screenings have been scheduled in conjunction with this gallery exhibition. Programs are free and are by reservation only. Tickets may be Joan Quinn Captured reserved at www.glendalearts.org. Join us for the opening reception on Saturday, June 28th, 7:00pm – 10:00pm. 6/28 EmErging LandscapE: 7/17 WarhoL/basquiat/quinn Los angeles 5:00pm film Jean Michel Basquiat: The exhibition ‘Joan Quinn Captured’ will 2:00pm panel Modern Art in Los Angeles: The Radiant Child showcase what is perhaps the largest portrait ‘Cool School’ Oral History Ed Moses 6:30pm panel Warhol & Basquiat: collection by contemporary artists in the world, 3:00PM film LA Suggested by the Art The Magazine of the 80s, Joan including such luminaries as Jean-Michel of Ed Ruscha Quinn’s work for Interview, the Basquiat, Shepard Fairey, Frank Gehry, Manipulator & Stuff Magazine; Robert Graham, David Hockney, Ed Ruscha, 4:30PM panel Los Angeles and the Contemporary Art Dawn Special Speaker Matthew Rolston Beatrice Wood and photographers Robert 7:00pm film Andy Warhol: Mapplethorpe, Helmut Newton, Matthew Rolston and Arthur A Documentary Film Tress. For the first time, this portrait collection will be exhibited in 7/3 EtErnaL rEturn collaboration with renowned works of the artists encouraging a 5:00pm film Beatrice Wood: Mama of Dada dialogue between the portraits and specific artist movements. The 7/24 don bachardy exhibition will also portray the world Joan Agajanian Quinn captured 6:30pm film Duggie Fields’ Jangled 6:00pm film Chris & Don: A Love Story as editor for her close friend Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, 7:00pm talk Guest Artist Duggie Fields 7:30pm film Memories of Berlin: along with contributions to some of the most important fanzines of 8:00pm film The Great Wen the 1980’s that are proof of her role as a critical taste maker of her The Twilight of Weimar Culture time. -

By Jennet Conant

he Man Shot Director Oliver Stone turns7 his obsession with all that is shameful and unresolved in American history to the mysteries of the Kennedy assassination By Jennet Conant When Pauline Kael, the legendary critic for The New Yorker, announced her retirement last year, she listed as one of her reasons for leaving that she couldn't hear to watch another Oliver Stone film. She hadn't even seen The Doors yet. Ending a twenty-three—year career rates as a mild reaction compared to the effect two or three hours alone in a dark room with an Oliver Stone film has had on some folks: The Turks reviled him for what they perceived to be the negative stereotypes in Mid- night Express. Chinese-Americans organized nation- wide protests and boycotts over the racism in Year of the Dragon. And the Cubans put out the unwelcome mat in Miami due to the sadism in Scarface. And those were just his screenplays. His early directorial efforts were no more popular-1981's The Hand was a low-budget horror pic about a severed mitt with murderous tendencies that one critic found so offensive, he immediately hailed Stone as the Antichrist of moviemaking. Ten years, six movies and three Oscars later, Oliver Stone with costner, whose casting as fin Garrison has fueled skepticism about JFK. Stone is still the auteur everyone loves to hate. No matter Pfeifer, "011ie's very much the sensitive brute." that Platoon and Born on the Fourth of July made Vietnam It's almost spooky how much Stone recalls Brando's Waterfront, all raw vets cry and put the country on the couch for some collec- beefy, brooding longshoreman in On the tive-guilt therapy. -

Stroboscopic: Andy Warhol and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2014 Stroboscopic: Andy Warhol and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Custom Citation H. King, "Stroboscopic: Andy Warhol and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable," Criticism 56.3 (Fall 2014): 457-479. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/72 For more information, please contact [email protected]. King 6/15/15 Page 1 of 30 Stroboscopic:+Andy+Warhol+and+the+Exploding+Plastic+Inevitable+ by+Homay+King,+Associate+Professor,+Department+of+History+of+Art,+Bryn+Mawr+College+ Published+in+Criticism+56.3+(Fall+2014)+ <insert+fig+1+near+here>+ + Pops+and+Flashes+ At+least+half+a+dozen+distinct+sources+of+illumination+are+discernible+in+Warhol’s+The+ Velvet+Underground+in+Boston+(1967),+a+film+that+documents+a+relatively+late+incarnation+of+ Andy+Warhol’s+Exploding+Plastic+Inevitable,+a+multimedia+extravaganza+and+landmark+of+ the+expanded+cinema+movement+featuring+live+music+by+the+Velvet+Underground+and+an+ elaborate+projected+light+show.+Shot+at+a+performance+at+the+Boston+Tea+Party+in+May+of+ 1967,+with+synch+sound,+the+33\minute+color+film+combines+long+shots+of+the+Velvet+ -

100 Cans by Andy Warhol

Art Masterpiece: 100 Cans by Andy Warhol Oil on canvas 72 x 52 inches (182.9 x 132.1 cm) Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery Keywords: Pop Art, Repetition, Complimentary Colors Activity: 100 Can Collective Class Mural Grade: 5th – 6th Meet the Artist • Born Andrew Warhol in 1928 near Pittsburgh, Pa. to Slovak immigrants. His father died in a construction accident when Andy was 13 years old. • He is known as an American painter, film-maker, publisher and major figure in the pop art movement. • Warhol was a sickly child, his mom would give him a Hershey bar for every coloring book page he finished. He excelled in art and won a scholarship to college. • After college, he moved to New York City and became a magazine illustrator – became known for his drawings of shoes. His mother lived with him – they had no hot water, the bathtub was in the kitchen and had up to 20 cats living with them. Warhol ate tomato soup every day for lunch. Chandler Unified School District Art Masterpiece • In the 1960’s, he started to make paintings of famous American products such as soup cans, coke bottles, dollar signs & celebrity portraits. He became known as the Prince of Pop – he brought art to the masses by making art out of daily life. • Warhol began to use a photographic silk-screen process to produce paintings and prints. The technique appealed to him because of the potential for repeating clean, hard-edged shapes with bright colors. • Andy wanted to remove the difference between fine art and the commercial arts used for magazine illustrations, comic books, record albums or ad campaigns. -

Andy Warhol Exhibit American Fare Summer Sets

NYC ® Monthly JULY 2015 JULY 2015 JULY NYC MONTHLY.COM VOL. 5 NO.7 VOL. AMERICAN FARE AMERICAN CUISINE AT ITS FINEST SUMMER SETS HEADLINING ACTS YOU CAN'T MISS ANDY WARHOL EXHIBIT AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART B:13.125” T:12.875” C M Y K S:12.75” The Next Big Thing Is Here lated. Appearance of device may vary. B:9.3125” S:8.9375” T:9.0625” The world’s frst dual-curved smartphone display Available now. Learn more at Samsung.com/GS6 ©2015 Samsung Electronics America, Inc. and Galaxy S are trademarks of Co., Ltd. Screen images simu FS:6.3125” FS:6.3125” F:6.4375” F:6.4375” 304653rga03_HmptMnthy TL Project Title: US - GS6_2015_S5053 Job Number: S5053 Executive Creative Director: None E.C.D. C.D. A.C.D A.D. C.W. Creative Director: None Client: SAMSUNG Bleed: 13.125” x 9.3125” Associate Creative Director: None Media: MAGAZINE Trim 1: 12.875” x 9.0625” Art Director: None Photographer: None Trim 2: None Copywriter: None Art Buyer: None STUDIO PRODUCTION IA PRODUCER ACCOUNT EX. ART BUYER Illustrator: None Live: 12.75” x 8.9375” Print Production: None Insertion Date: None Gutter: 0.125” Studio Manager: None Account Executive: None Traffic: None Publications/Delivery Company: Hamptons Monthly FILE IS BUILT AT: 100% THIS PRINT-OUT IS NOT FOR COLOR. 350 West 39th Street New York, NY 10018 212.946.4000 Round: 1 Version: C PACIFIC DIGITAL IMAGE • 333 Broadway, San Francisco CA 94133 • 415.274.7234 • www.pacdigital.com Filename:304653rga03_HmptMnthy.pdf_wf02 Operator:SpoolServer Time:13:37:40 Colors:Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black Date:15-05-06 NOTE TO RECIPIENT: This file is processed using a Prinergy Workflow System with an Adobe Postscript Level 3 RIP. -

Exploring Films About Ethical Leadership: Can Lessons Be Learned?

EXPLORING FILMS ABOUT ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: CAN LESSONS BE LEARNED? By Richard J. Stillman II University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center Public Administration and Management Volume Eleven, Number 3, pp. 103-305 2006 104 DEDICATED TO THOSE ETHICAL LEADERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE 9/11 TERROIST ATTACKS — MAY THEIR HEORISM BE REMEMBERED 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 106 Advancing Our Understanding of Ethical Leadership through Films 108 Notes on Selecting Films about Ethical Leadership 142 Index by Subject 301 106 PREFACE In his preface to James M cG regor B urns‘ Pulitzer–prizewinning book, Leadership (1978), the author w rote that ―… an im m ense reservoir of data and analysis and theories have developed,‖ but ―w e have no school of leadership.‖ R ather, ―… scholars have worked in separate disciplines and sub-disciplines in pursuit of different and often related questions and problem s.‖ (p.3) B urns argued that the tim e w as ripe to draw together this vast accumulation of research and analysis from humanities and social sciences in order to arrive at a conceptual synthesis, even an intellectual breakthrough for understanding of this critically important subject. Of course, that was the aim of his magisterial scholarly work, and while unquestionably impressive, his tome turned out to be by no means the last word on the topic. Indeed over the intervening quarter century, quite to the contrary, we witnessed a continuously increasing outpouring of specialized political science, historical, philosophical, psychological, and other disciplinary studies with clearly ―no school of leadership‖with a single unifying theory emerging. -

Jean-Michel Basquiat – Gift of the Elegant Clochard

Jean-Michel Basquiat – Gift of the Elegant Clochard KAT BALKOSKI “I’d rather have a Jean-Michel [Basquiat] than a Cy Twombly. I do not live in the classical city. My neighborhood is unsafe. Also, I want my home to look like a pile of junk to burglars.”1 So joked René Ricard in his groundbreaking piece on Jean-Michel Basquiat for Artforum, “The Radiant Child,” in 1981. This kind of characterization of Basquiat’s art as “junk” and Ricard’s later description of the young artist having the affected “elegance of the clochard who lights up a megot with his pinkie raised” helped set the stage for the art world’s problematic fascination with Basquiat as the “true voice of the ghetto.”2 “Famous Moon King,” (fig. 1)—oil and acrylic on canvas, 180 x 261 cm—was painted at the height of Basquiat’s short career, in1984/85. It demonstrates a sophistication of the visual vocabulary and idiosyncratic graffiti style Basquiat was already developing in 1981. The work makes use of heterogeneous representational styles: three darkly filled-in figures with brightly outlined visible innards seem to float above a chaotic background of interpenetrative vignettes of line-drawn faces, body parts, stick figures, words and symbols. There is a logic of accumulation and appropriation to this work, consistent with the medium of graffiti, Diaspora culture, and the hoarding practices of the homeless and dispossessed. Familiarity with Basquiat’s biography is fundamental to the interpretation of his work, which is as much about the elaboration of an aesthetic identity within a worn out cultural vocabulary as it is “about” anything else. -

Warhol, Andy (As Filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol

Warhol, Andy (as filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol. by David Ehrenstein Image appears under the Creative Commons Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Courtesy Jack Mitchell. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com As a painter Andy Warhol (the name he assumed after moving to New York as a young man) has been compared to everyone from Salvador Dalí to Norman Rockwell. But when it comes to his role as a filmmaker he is generally remembered either for a single film--Sleep (1963)--or for works that he did not actually direct. Born into a blue-collar family in Forest City, Pennsylvania on August 6, 1928, Andrew Warhola, Jr. attended art school at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh. He moved to New York in 1949, where he changed his name to Andy Warhol and became an international icon of Pop Art. Between 1963 and 1967 Warhol turned out a dizzying number and variety of films involving many different collaborators, but after a 1968 attempt on his life, he retired from active duty behind the camera, becoming a producer/ "presenter" of films, almost all of which were written and directed by Paul Morrissey. Morrissey's Flesh (1968), Trash (1970), and Heat (1972) are estimable works. And Bad (1977), the sole opus of Warhol's lover Jed Johnson, is not bad either. But none of these films can compare to the Warhol films that preceded them, particularly My Hustler (1965), an unprecedented slice of urban gay life; Beauty #2 (1965), the best of the films featuring Edie Sedgwick; The Chelsea Girls (1966), the only experimental film to gain widespread theatrical release; and **** (Four Stars) (1967), the 25-hour long culmination of Warhol's career as a filmmaker. -

Album Review of the Velvet Underground & Nico

Album Review of The Velvet Underground & Nico – Artifacts Journal - University of Mi... Page 1 of 4 University of Missouri A Journal of Undergraduate Writing Album Review of The Velvet Underground & Nico Sam Jennings Sam Jennings started attending the University of Missouri in 2012 and is currently pursuing a bachelor of music performance in guitar. He writes in his spare time and fronts a local Columbia rock band, “The Rollups”. He is thankful to Dr. Michael J. Budds for encouraging him and his submission to this journal. He wrote this paper as one part of a multi-paper project in Historical Studies in Jazz and Popular Music, taught by Dr. Michael J. Budds. They were expected to choose a musician (before 1970) and review a full-length LP by that artist; he felt particularly inclined to make the case for a set of truly bizarre, radical artists who have been historically misunderstood and misaligned. When The Velvet Underground & Nico was released in March of 1967, it was to a public that hardly cared and a critical establishment that could not make heads or tails of it. Its sales were dismal, due in part to legal troubles, and MGM’s bungled attempts at promoting the record. The Velvet Underground’s seedy, druggy music defiantly reflected an urban attitude even closer to the beatniks than Bob Dylan and even more devoted to rock n’ roll primitivism than The Rolling Stones or The Who. Nevertheless, the recording had no place in a landscape soon to be dominated by San Francisco psychedelics and high- concept British pop. -

Exhibiting Warhols's Screen Tests

1 EXHIBITING WARHOL’S SCREEN TESTS Ian Walker The work of Andy Warhol seems nighwell ubiquitous now, and its continuing relevance and pivotal position in recent culture remains indisputable. Towards the end of 2014, Warhol’s work could be found in two very different shows in Britain. Tate Liverpool staged Transmitting Andy Warhol, which, through a mix of paintings, films, drawings, prints and photographs, sought to explore ‘Warhol’s role in establishing new processes for the dissemination of art’.1 While, at Modern Art Oxford, Jeremy Deller curated the exhibition Love is Enough, bringing together the work of William Morris and Andy Warhol to idiosyncratic but striking effect.2 On a less grand scale was the screening, also at Modern Art Oxford over the week of December 2-7, of a programme of Warhol’s Screen Tests. They were shown in the ‘Project Space’ as part of a programme entitled Straight to Camera: Performance for Film.3 As the title suggests, this featured work by a number of artists in which a performance was directly addressed to the camera and recorded in unrelenting detail. The Screen Tests which Warhol shot in 1964-66 were the earliest works in the programme and stood, as it were, as a starting point for this way of working. Fig 1: Cover of Callie Angell, Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests, 2006 2 How they were made is by now the stuff of legend. A 16mm Bolex camera was set up in a corner of the Factory and the portraits made as the participants dropped by or were invited to sit. -

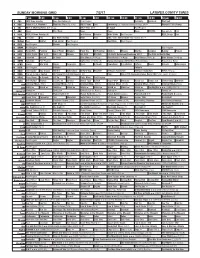

Sunday Morning Grid 7/2/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/2/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Celebrity Hot Seat PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Swimming U.S. National Championships. (N) Å Women’s PGA Champ. 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News XTERRA Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid 2017 U.S. Senior Open Final Round. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap 2017 The Path to Wealth-May 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho (N) Duro pero seguro (1978) María Elena Velasco. Recuerda y Gana 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Película Película 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog WordGirl Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow NOVA (TVG) Å 52 KVEA Hoy en la Copa Confed Un Nuevo Día Edición Especial (N) Copa Copa FIFA Confederaciones Rusia 2017 Chile contra Alemania. -

Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, No

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Peter R. Kalb, review of Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11870. Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation Curated by: Liz Munsell, The Lorraine and Alan Bressler Curator of Contemporary Art, and Greg Tate Exhibition schedule: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, October 18, 2020–July 25, 2021 Exhibition catalogue: Liz Munsell and Greg Tate, eds., Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, exh. cat. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2020. 199 pp.; 134 color illus. Cloth: $50.00 (ISBN: 9780878468713) Reviewed by: Peter R. Kalb, Cynthia L. and Theodore S. Berenson Chair of Contemporary Art, Department of Fine Arts, Brandeis University It may be argued that no artist has carried more weight for the art world’s reckoning with racial politics than Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988). In the 1980s and 1990s, his work was enlisted to reflect on the Black experience and art history; in the 2000 and 2010s his work diversified, often single-handedly, galleries, museums, and art history surveys. Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation attempts to share in these tasks. Basquiat’s artwork first appeared in lower Manhattan in exhibitions that poet and critic Rene Ricard explained, “made us accustomed to looking at art in a group, so much so that an exhibit of an individual’s work seems almost antisocial.”1 The earliest efforts to historicize the East Village art world shared this spirit of sociability.