Greenwich Bay: an Ecological History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9. Ocean Deoxygenation: Impacts on Ecosystem Services and People Hannah R

9. Ocean deoxygenation: Impacts on ecosystem services and people Hannah R. Bassett, Alexandra Stote, Edward H. Allison Ocean deoxygenation: Impacts on ecosystem 9 services and people Hannah R. Bassett1, Alexandra Stote1, Edward H. Allison1,2 1 School of Marine and Environmental Affairs, University of Washington, Seattle, USA 2 Worldfish, Penang, Malaysia Summary • Effects of ocean deoxygenation on people remain understudied and inherently challenging to assess. Few studies address the topic and those that do generally include more readily quantified economic losses associated with ocean deoxygenation, exclude non-use and existence value as well as cultural services, and focus on relatively small, bounded systems in capitalized regions. Despite the lack of extensive research on the topic, current knowledge based in both the natural and social sciences, as well as the humanities, can offer useful insights into what can be expected from continued ocean deoxygenation in terms of generalized impact pathways. • People receive benefits from ocean ecosystem services in the form of well-being (assets, health, good social relations, security, agency). Ecosystem services are translated to human well-being via social mediation, such that differences in levels of power and vulnerability determine how different social groups will experience hazards created by continued ocean deoxygenation. Despite not knowing the precise mechanisms of ocean deoxygenation-driven biophysical change, established social mechanisms suggest that ocean deoxygenation will exacerbate existing social inequities. • Reductions in dissolved oxygen (DO) are generally expected to disrupt ecosystem functioning and degrade habitats, placing new challenges and costs on existing systems for ocean resource use. Coral reefs, wetlands and marshes, and fish and crustaceans are relatively more susceptible to negative effects of ocean deoxygenation. -

Prudence Island Narragansett Bay Research Reserve

Last Updated 1/20/07 Prudence Island Narragansett Bay Research Reserve Background Prudence Island is located in the geographic center of Narragansett Bay. The island is approximately 7 miles long and 1 mile across at its widest point. Located at the south end of the island is the Narragansett Bay Research Reserve’s Lab & Learning Center. The Center contains educational exhibits, a public meeting area, library, and research labs for staff and visiting scientists. The Reserve manages approximately 60% of Prudence; the largest components are at the north and south ends of Prudence Island. The vegetation on Prudence reflects the extensive farming that took place in the area until the early 1900s. After the fields were abandoned, woody plants gradually replaced the herbaceous species. The uplands are now covered with a dense shrub growth of bayberry, blueberry, arrowwood, and shadbush interspersed with red cedar, red maple, black cherry, pitch pine and oak. Green briar and Asiatic bittersweet cover much of the island as well. Prudence Island also supports one of the most dense white-tailed deer herds in New England . Raccoons, squirrels, Eastern red fox, Eastern cottontail rabbits, mink, and white-footed mice are plentiful. The large, salt marshes at the north end of Prudence are used as feeding areas by a number of large wading birds such as great and little blue herons, snowy and great egrets, black-crowned night herons, green-backed herons and glossy ibis. Between September and May, Prudence Island is also used as a haul-out site for harbor seals. History of Prudence Island Before colonial times, Prudence and the surrounding islands were under the control of the Narragansett Native Americans. -

Patience Island Narragansett Bay Research Reserve

Last Updated 1/20/07 Patience Island Narragansett Bay Research Reserve Background This 207-acre island lies to the west of northern Prudence Island. At their closest, the two islands are only 900 feet apart. The Patience Island is dominated by tall shrubs interspersed with red cedar and black cherry. Common shrubs include bayberry, highbush blueberry, and shadbush. Much of the island is also covered by brier, Asiatic bittersweet and poison ivy. A deciduous forest is gradually replacing the shrub habitat in some parts of the island. The small salt marsh on the southeastern shore provides habitat for seablite, a plant species common in other areas of the country, but rare in Rhode Island. The upland area of Patience Island supports a variety of wildlife including white-tailed deer, red fox, and Eastern cottontail rabbits. Coastal areas are used extensively by migrant and wintering waterfowl species such as horned grebes, greater scaup, black ducks and scoters. Quahogs are abundant in the sandy sediment. There is no ferry service available to this island. Visitors are welcome but you must provide your own transportation. Be aware that there is a high population of ticks, the trails may be overgrown, and camping is not permitted. History of Patience Island Historically, the Patience Island Farm covered an area of approximately 200 acres, nearly the entire island, and was a working farm as early as the mid-seventeenth century. The farm buildings were burned by the British during the Revolutionary War. After the war, the buildings were rebuilt and the farm remained in operation until the early twentieth century. -

The History and Future of Narragansett Bay

The History and Future of Narragansett Bay Capers Jones Universal Publishers Boca Raton, Florida USA • 2006 The History and Future of Narragansett Bay Copyright © 2006 Capers Jones All rights reserved. Universal Publishers Boca Raton , Florida USA • 2006 ISBN: 1-58112-911-4 Universal-Publishers.com Table of Contents Preface ...............................................................................................................................ix Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................... xiii Introduction..................................................................................................................... 15 Chapter 1 Geological Origins of Narragansett Bay.................................................................... 17 Defining Narragansett Bay ........................................................................................ 22 The Islands of Narragansett Bay............................................................................... 23 Earthquakes & Sea Level Changes of Narragansett Bay....................................... 24 Hurricanes & Nor’easters beside Narragansett Bay .............................................. 25 Meteorology of Hurricanes........................................................................................ 26 Meteorology of Nor’easters ....................................................................................... 27 Summary of Bay History........................................................................................... -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

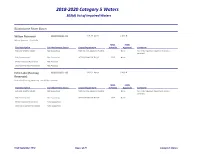

2018-2020 Category 5 Waters 303(D) List of Impaired Waters

2018-2020 Category 5 Waters 303(d) List of Impaired Waters Blackstone River Basin Wilson Reservoir RI0001002L-01 109.31 Acres CLASS B Wilson Reservoir. Burrillville TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Not Assessed Secondary Contact Recreation Not Assessed Echo Lake (Pascoag RI0001002L-03 349.07 Acres CLASS B Reservoir) Echo Lake (Pascoag Reservoir). Burrillville, Glocester TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Secondary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Draft September 2020 Page 1 of 79 Category 5 Waters Blackstone River Basin Smith & Sayles Reservoir RI0001002L-07 172.74 Acres CLASS B Smith & Sayles Reservoir. Glocester TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Secondary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Slatersville Reservoir RI0001002L-09 218.87 Acres CLASS B Slatersville Reservoir. Burrillville, North Smithfield TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting COPPER 2026 None Not Supporting LEAD 2026 None Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. -

RI DEM/Water Resources

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Water Resources WATER QUALITY REGULATIONS July 2006 AUTHORITY: These regulations are adopted in accordance with Chapter 42-35 pursuant to Chapters 46-12 and 42-17.1 of the Rhode Island General Laws of 1956, as amended STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Water Resources WATER QUALITY REGULATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS RULE 1. PURPOSE............................................................................................................ 1 RULE 2. LEGAL AUTHORITY ........................................................................................ 1 RULE 3. SUPERSEDED RULES ...................................................................................... 1 RULE 4. LIBERAL APPLICATION ................................................................................. 1 RULE 5. SEVERABILITY................................................................................................. 1 RULE 6. APPLICATION OF THESE REGULATIONS .................................................. 2 RULE 7. DEFINITIONS....................................................................................................... 2 RULE 8. SURFACE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS............................................... 10 RULE 9. EFFECT OF ACTIVITIES ON WATER QUALITY STANDARDS .............. 23 RULE 10. PROCEDURE FOR DETERMINING ADDITIONAL REQUIREMENTS FOR EFFLUENT LIMITATIONS, TREATMENT AND PRETREATMENT........... 24 RULE 11. PROHIBITED -

City of Newport Comprehensive Harbor Management Plan

Updated 1/13/10 hk Version 4.4 City of Newport Comprehensive Harbor Management Plan The Newport Waterfront Commission Prepared by the Harbor Management Plan Committee (A subcommittee of the Newport Waterfront Commission) Version 1 “November 2001” -Is the original HMP as presented by the HMP Committee Version 2 “January 2003” -Is the original HMP after review by the Newport . Waterfront Commission with the inclusion of their Appendix K - Additions/Subtractions/Corrections and first CRMC Recommended Additions/Subtractions/Corrections (inclusion of App. K not 100% complete) -This copy adopted by the Newport City Council -This copy received first “Consistency” review by CRMC Version 3.0 “April 2005” -This copy is being reworked for clerical errors, discrepancies, and responses to CRMC‟s review 3.1 -Proofreading – done through page 100 (NG) - Inclusion of NWC Appendix K – completely done (NG) -Inclusion of CRMC comments at Appendix K- only “Boardwalks” not done (NG) 3.2 -Work in progress per CRMC‟s “Consistency . Determination Checklist” : From 10/03/05 meeting with K. Cute : From 12/13/05 meeting with K. Cute 3.3 -Updated Approx. J. – Hurricane Preparedness as recommend by K. Cute (HK Feb 06) 1/27/07 3.4 - Made changes from 3.3 : -Comments and suggestions from Kevin Cute -Corrects a few format errors -This version is eliminates correction notations -1 Dec 07 Hank Kniskern 3.5 -2 March 08 revisions made by Hank Kniskern and suggested Kevin Cute of CRMC. Full concurrence. -Only appendix charts and DEM water quality need update. Added Natural -

CHAPTER 4. Ecological Geography of the NBNERR

CHAPTER 4. Ecological Geography of the NBNERR CHAPTER 4. Ecological Geography of the NBNERR Kenneth B. Raposa 23 An Ecological Profile of the Narragansett Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve Figure 4.1. Geographic setting of the NBNERR, including the extent of the 4,818 km2 (1,853-square-mile) Narragan- sett Bay watershed. GIS data sources courtesy of RIGIS (www.edc.uri.edu/rigis/) and Massachusetts GIS (www.mass. gov/mgis/massgis.htm). 24 CHAPTER 4. Ecological Geography of the NBNERR Ecological Geography of the NBNERR Geographic Setting Program in 2001. Annual weather patterns on Pru- dence Island are similar to those on the mainland, Prudence Island is located roughly in at least when considering air temperature, wind the center of Narragansett Bay, R.I., bounded by speed, and barometric pressure (Figure 4.3). 41o34.71’N and 41o40.02’N, and 71o18.16’W and Using recent data collected from the 71o21.24’W. Metropolitan Providence lies 14.4 NBNERR weather station, some annual patterns kilometers (km) (9 miles) to the north and the city are clear. For example, air temperature, relative of Newport lies 6.4 km (4 miles) to the south of humidity, and the amount of photosynthetically Prudence (Fig 4.1). Because of its central location, active radiation (PAR) all clearly peak during the Prudence Island is affected by numerous water summer months (Fig. 4.3). The total amount of masses in Narragansett Bay including nutrient-rich precipitation is generally highest during spring and freshwaters fl owing downstream from the Provi- fall, but this pattern is not as strong as the former dence and Taunton rivers and oceanic tidal water parameters based on these limited data. -

180 Potowomut River Basin

180 POTOWOMUT RIVER BASIN 01117000 HUNT RIVER NEAR EAST GREENWICH, RI LOCATION.--Lat 41°38’28", long 71°26’45", Washington County, Hydrologic Unit 01090004, on right bank 45 ft upstream from Old Forge Dam in North Kingstown, 1.5 mi south of East Greenwich, and 2.5 mi upstream from mouth. DRAINAGE AREA.--22.9 mi2. PERIOD OF RECORD.--Discharge: August 1940 to current year. Prior to October 1977, published as "Potowomut River." Water-quality records: Water years 1977–81. REVISED RECORDS.--WSP 1621: 1957–58; 1995. GAGE.--Water-stage recorder. Datum of gage is 5.42 ft above sea level. REMARKS.--Records good. Flow affected by diversions for supply of East Greenwich, North Kingstown, Warwick, and Quonset Point (formerly U.S. Naval establishments). AVERAGE DISCHARGE.--62 years, 46.9 ft3/s. EXTREMES FOR PERIOD OF RECORD.--Maximum discharge, 1,020 ft3/s, June 6, 1982, gage height, 3.73 ft, from rating curve extended above 440 ft3/s; maximum gage height of 6.78 ft, Aug. 31, 1954 (backwater from hurricane tidal wave); no flow at times in water years 1948, 1960, 1971, 1975–77, 1983, 1986–87, caused by closing of gate at Old Forge Dam. EXTREMES OUTSIDE PERIOD OF RECORD.--Maximum stage since at least 1915, about 8.5 ft Sept. 21, 1938 (backwater from hurricane tidal wave). EXTREMES FOR CURRENT YEAR.--Maximum discharge, 836 ft3/s, Mar. 22, gage height, 3.43 ft; minimum, 6.0 ft3/s, Oct. 30, Sept. 20. DISCHARGE, CUBIC FEET PER SECOND, WATER YEAR OCTOBER 2000 TO SEPTEMBER 2001 DAILY MEAN VALUES DAY OCT NOV DEC JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP 1 13 7.7 -

Dam Safety Program

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND 2009 Annual Report to the Governor on the Activities of the DAM SAFETY PROGRAM Overtopping earthen embankment of Creamer Dam (No. 742), Tiverton Department of Environmental Management Prepared by the Office of Compliance and Inspection TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORY OF RHODE ISLAND’S DAM SAFETY PROGRAM....................................................................3 STATUTES................................................................................................................................................3 GOVERNOR’S TASK FORCE ON DAM SAFETY AND MAINTENANCE .................................................3 DAM SAFETY REGULATIONS .................................................................................................................4 DAM CLASSIFICATIONS..........................................................................................................................5 INSPECTION PROGRAM ............................................................................................................................7 ACTIVITIES IN 2009.....................................................................................................................................8 UNSAFE DAMS.........................................................................................................................................8 INSPECTIONS ........................................................................................................................................10 High Hazard Dam Inspections .............................................................................................................10 -

State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations Department of Environmental Management Division of Fish and Wildlife Division O

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT DIVISION OF FISH AND WILDLIFE DIVISION OF LAW ENFORCEMENT Rhode Island Marine Fisheries Regulations SHELLFISH October 23, 2014 AUTHORITY: Title 20, Chapters 42-17.1, 42-17.6, and 42-17.7, and in accordance with Chapter 42-35- 18(b)(5), Administrative Procedures Act of the Rhode Island General Laws of 1956, as amended. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. PURPOSE ....................................................................................................... 3 2. AUTHORITY .................................................................................................... 3 3. APPLICATION ................................................................................................. 3 4. SEVERABILTY ................................................................................................ 3 5. SUPERSEDED RULES AND REGULATIONS ................................................ 3 6. DEFINTIONS .................................................................................................. 3 7. LICENSE REQUIRED .................................................................................... 7 8. GENERAL PROVISIONS ............................................................................... 8 9. EQUIPMENT PROVISIONS AND HARVEST METHODS .............................. 9 10. MINIMIM SIZES ............................................................................................ 12 11. SEASONS ...................................................................................................