What Predicts Submissive Fantasies for Women? by Alison Anne Ziegler a Dissertation Submitted in Part

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Sadomasochism: Taxonomies and Language

Nicole Eitmann On Sadomasochism: Taxonomies and Language Governments try to regulate sadomasochistic activities (S/M). Curiously, though, no common definition of S/M exists and there is a dearth of statistically valid social science research on who engages in S/M or how participants define the practice. This makes it hard to answer even the most basic questions shaping state laws and policies with respect to S/M. This paper begins to develop a richer definition of sadomasochistic activities based on the reported common practices of those engaging in S/M. The larger question it asks, though, is why so little effort has been made by social scientists in general and sex researchers in particular to understand the practice and those who participate in it. As many social sci- entists correctly observe, sadomasochism has its “basis in the culture of the larger society.”1 Rethinking sadomasochism in this way may shed some light on the present age. A DEFINITIONAL QUAGMIRE In Montana, sadomasochistic abuse includes the depiction of a per- son clad in undergarments or in a revealing or bizarre costume.2 In Illinois, it is illegal to distribute or sell obscene material—defined in part as “sado- masochistic sexual acts, whether normal or perverted, actual or simu- lated.”3 The lack of a clear definition of what constitutes S/M is one major difficulty in developing appropriate policies with respect to S/M activities. Clearly, S/M means different things to different people, and there is a wide range of possible S/M activities—from light spanking or -

Age and Sexual Consent

Per Se or Power? Age and Sexual Consent Joseph J. Fischel* ABSTRACT: Legal theorists, liberal philosophers, and feminist scholars have written extensively on questions surrounding consent and sexual consent, with particular attention paid to the sorts of conditions that validate or vitiate consent, and to whether or not consent is an adequate metric to determine ethical and legal conduct. So too, many have written on the historical construction of childhood, and how this concept has influenced contemporary legal culture and more broadly informed civil society and its social divisions. Far less has been written, however, on a potent point of contact between these two fields: age of consent laws governing sexual activity. Partially on account of this under-theorization, such statutes are often taken for granted as reflecting rather than creating distinctions between adults and youth, between consensual competency and incapacity, and between the time for innocence and the time for sex. In this Article, I argue for relatively modest reforms to contemporary age of consent statutes but propose a theoretic reconstruction of the principles that inform them. After briefly historicizing age of consent statutes in the United States (Part I), I assert that the concept of sexual autonomy ought to govern legal regulations concerning age, age difference, and sexual activity (Part II). A commitment to sexual autonomy portends a lowered age of sexual consent, decriminalization of sex between minors, heightened legal supervision focusing on age difference and relations of dependence, more robust standards of consent for sex between minors and between minors and adults, and greater attention to the ways concerns about age, age difference, and sex both reflect and displace more normatively apt questions around gender, gendered power and submission, and queer sexuality (Part III). -

Themes of SM Expression Charles Moser and Peggy J

3 Themes of SM Expression Charles Moser and Peggy J. Kleinplatz SM (also known as BDSM, i.e. Bondage and Discipline, Dominance and Submission and Sadism and Masochism) is a term used to describe a variety of sexual behaviours that have an implicit or explicit power differential as a significant aspect of the erotic interaction. Of course there are other sexual interactions or behaviours that have an implicit power differential, but that power differential is not generally eroticized in non-SM interactions. Sex partners may even disagree if a particular interaction or relationship constitutes SM, each seeing it from a different perspective. The boundaries between SM and non-SM interactions are not always clear, which is why self-definition is crucial for understanding SM phenomena. Colloquially the set of SM inclinations has been referred to deris- ively as an interest in ‘whips and chains’, but is much more complex and varied than suggested by that description. Practitioners use both numerous academic terms and jargon (e.g. S/M, B/D, WIITWD [i.e. what it is that we do], D/s, Bondage, Leather, Kink) to refer to these interests. They have been labelled controversially in the psychiatric liter- ature with diagnostic labels such as paraphilia, sadomasochism, sexual sadism, sexual masochism and fetishism. There is no evidence that the descriptions in the psychiatric literature resemble the individuals who self-identify as SM participants or that SM participants understand the implications of adopting the psychiatric terms as self-descriptors. Judging from the proliferation of SM themes in sexually explicit media, references in mainstream books, film and the news media, as well as academic studies and support groups, it is reasonable to conclude that SM is an important sexual interest for a significant number of indi- viduals. -

ON INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION and SEXUALIZED VIOLENCE in COLLEGE WOMEN Marina Leigh Costanzo

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Graduate School Professional Papers 2018 ON INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION AND SEXUALIZED VIOLENCE IN COLLEGE WOMEN Marina Leigh Costanzo Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Recommended Citation Costanzo, Marina Leigh, "ON INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION AND SEXUALIZED VIOLENCE IN COLLEGE WOMEN" (2018). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11264. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11264 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION AND SEXUALIZED VIOLENCE IN COLLEGE WOMEN By MARINA LEIGH COSTANZO B.A., University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 2010 M.A., University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, CO, 2013 Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in Clinical Psychology The University of Montana Missoula, MT August 2018 Approved by: Scott Whittenburg, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Christine Fiore, Chair Psychology Laura Kirsch Psychology Jennifer Robohm Psychology Gyda Swaney Psychology Sara Hayden Communication Studies INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION AND SEXUALIZED VIOLENCE ii Costanzo, Marina, PhD, Summer 2018 Clinical Psychology Abstract Chairperson: Christine Fiore Sexualized violence on college campuses has recently entered the media spotlight. One in five women are sexually assaulted during college and over 90% of these women know their attackers (Black et al., 2011; Cleere & Lynn, 2013). -

Structural Sexism and Health in the United States by Patricia A. Homan

Structural Sexism and Health in the United States by Patricia A. Homan Department of Sociology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Linda K. George, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Scott M. Lynch, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Jen’nan G. Read ___________________________ Laura S. Richman ___________________________ Tyson H. Brown Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Sociology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Structural Sexism and Health in the United States by Patricia A. Homan Department of Sociology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Linda K. George, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Scott M. Lynch, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Jen’nan G. Read ___________________________ Laura S. Richman ___________________________ Tyson H. Brown An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Sociology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Patricia A. Homan 2018 Abstract In this dissertation, I seek to begin building a new line of health inequality research that parallels the emerging structural racism literature by developing theory and measurement for the new concept of structural sexism and examining its relationship to health. Consistent with contemporary theories of gender as a multilevel social system, I conceptualize and measure structural sexism as systematic gender inequality in power and resources at the macro-level (U.S. state), meso-level (marital dyad), and micro-level (individual). Through a series of quantitative analyses, I examine how various measures of structural sexism affect the health of men, women, and infants in the U.S. -

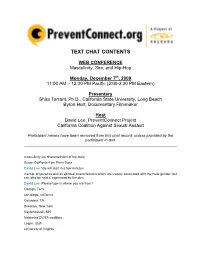

Text Chat Contents

TEXT CHAT CONTENTS WEB CONFERENCE Masculinity, Sex, and Hip-Hop Monday, December 7th, 2009 11:00 AM – 12:30 PM Pacific (2:00-3:30 PM Eastern) Presenters Shira Tarrant, Ph.D., California State University, Long Beach Byron Hurt, Documentary Filmmaker Host David Lee, PreventConnect Project California Coalition Against Sexual Assault Participant names have been removed from this chat record, unless provided by the participant in text. masculinity are characteristics of the male Susan DelPonte from Penn State David Lee: We will start in a few minutes mental, physical as well as spiritual characteristics which are usually associated with the male gender, but can also be held & expressed by females David Lee: Please type in where you are from? Georgia Tech san diego, california Columbia, TN Brooklyn, New York Naytahwaush, MN Nebraska DV/SA coalition Logan, Utah University of Virginia Text Chat Contents Fargo, ND Virginia Beach, VA Humboldt County, CA Austin, TX Atlanta Georgia Spirit Lake, Iowa Humboldt and Del Norte Counties Fairfax Virginia Jennifer Thomas, Atlanta Georgia Twin Cities, MN Harrisonburg, VA Tampa, FL Durango, CO David Lee: And what organization are you with? Grand Forks, ND Fayetteville, Arkansas and Jacquie Marroquin from Haven Women's Center of Stanislaus Marsha Landrith: Lakeview, Oregon Norfolk, VA DOVE Program Human Services Inc Crisis Center of Tampa Bay Nancy Boyle: Rape & Abuse Crisis Center, Fargo ND Patti Torchia, Springfield, IL Rape and Abuse Crisis Center, Fargo, ND North Coast Rape Crisis Team, Humboldt/Del Norte CA Local health department CAPSA Domestic violence/rape advocacy organization United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD Patricia Maarhuis & Ginny Hauser: WSU Pullman WA GA Commission on Family Violence Sexual Assault Services Org. -

Sexual Fantasy and Masturbation Among Asexual Individuals: an In-Depth Exploration

Arch Sex Behav (2017) 46:311–328 DOI 10.1007/s10508-016-0870-8 SPECIAL SECTION: THE PUZZLE OF SEXUAL ORIENTATION Sexual Fantasy and Masturbation Among Asexual Individuals: An In-Depth Exploration 1 1 2 Morag A. Yule • Lori A. Brotto • Boris B. Gorzalka Received: 4 January 2016 / Revised: 8 August 2016 / Accepted: 20 September 2016 / Published online: 23 November 2016 Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2016 Abstract Human asexuality is generally defined as a lack of pants(bothmenandwomen)wereequallylikelytofantasizeabout sexual attraction. We used online questionnaires to investigate topics such as fetishes and BDSM. reasons for masturbation, and explored and compared the con- tentsofsexualfantasiesofasexualindividuals(identifiedusing Keywords Asexuality Á Sexual orientation Á Masturbation Á the Asexual Identification Scale) with those of sexual individ- Sexual fantasy uals. A total of 351 asexual participants (292 women, 59 men) and 388sexualparticipants(221women,167men)participated.Asex- ual women were significantly less likely to masturbate than sexual Introduction women, sexual men, and asexual men. Asexual women were less likely to report masturbating for sexual pleasure or fun than their Although the definition of asexuality varies somewhat, the gen- sexualcounterparts, and asexualmen were less likely to reportmas- erallyaccepteddefinitionisthedefinitionforwardedbythelargest turbating forsexualpleasure than sexualmen. Both asexualwomen online web-community of asexual individuals (Asexuality Visi- andmen weresignificantlymorelikelythansexualwomenand -

Asexuality: Sexual Orientation, Paraphilia, Sexual Dysfunction, Or None of the Above?

Arch Sex Behav DOI 10.1007/s10508-016-0802-7 TARGET ARTICLE Asexuality: Sexual Orientation, Paraphilia, Sexual Dysfunction, or None of the Above? 1 2 Lori A. Brotto • Morag Yule Received: 30 December 2015 / Revised: 15 June 2016 / Accepted: 27 June 2016 Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2016 Abstract Although lack of sexual attraction was first quantified Introduction by Kinsey, large-scale and systematic research on the preva- lence and correlates of asexuality has only emerged over the Prior to 2004, asexuality was a term that was largely reserved past decade. Several theories have been posited to account for for describing the reproductive patterns of single-celled organ- thenatureofasexuality.Thegoalofthisreviewwastoconsider isms.Sincethen,however,empiricalresearchonthetopicof the evidence for whether asexuality is best classified as a psy- human asexuality—often defined as a lack of sexual attraction— chiatric syndrome (or a symptom of one), a sexual dysfunction, or has grown. Estimates from large-scale national probabil- a paraphilia. Based on the available science, we believe there is not ity studies of British residents suggest that approximately 0.4 % sufficient evidence to support the categorization of asexuality as a (Aicken,Mercer,&Cassel,2013;Bogaert,2013)to1%(Bogaert, psychiatric condition (or symptom of one) or as a disorder of 2004, 2013; Poston & Baumle, 2010) of the adult human popu- sexual desire. There is some evidence that a subset of self-iden- lation report never feeling sexually attracted to anyone, with rates tified asexuals have a paraphilia. We also considered evidence closer to 2 % for high school students from New Zealand supporting the classification of asexuality as a unique sexual orien- (Lucassen et al., 2011),andupto3.3%ofFinnishwomen tation. -

High Risk Sexual Offenders: the Association Between Sexual Paraphilias, Sexual Fantasy, and Psychopathy

HIGH RISK SEXUAL OFFENDERS: THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN SEXUAL PARAPHILIAS, SEXUAL FANTASY, AND PSYCHOPATHY by TABATHA FREIMUTH B.Sc., Okanagan University College, 2002 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In THE COLLEGE OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Interdisciplinary Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Okanagan) March 2008 © Tabatha Freimuth, BSc, January 2008 ABSTRACT High risk offenders are a complex and heterogeneous group of offenders about whom researchers, clinicians, and society still know relatively little. In response to the paucity of information that is specifically applicable to high risk offenders, the present study examined RCMP Integrated Sexual Predator Intelligence Network (ISPIN) data to investigate the relationship between sexual paraphilias, sexual fantasy, and psychopathy among 139 of the highest risk sexual offenders in British Columbia. The sample included 41 child molesters, 42 rapists, 18 rapist/molesters, 30 mixed offenders, and 6 “other” sexual offenders. The majority of offenders in this sample were diagnosed with one primary paraphilia (67%). Data analysis revealed significant differences between offender types for criminal history variables including past sexual and nonsexual convictions, number of victims, and age of offending onset. For example, offenders who victimized children (i.e., exclusive child molesters & rapist/molesters) had a greater number of past sexual convictions than did offenders who victimized adults exclusively. Further, there were significant differences between offender types for paraphilia diagnoses, sexual fantasy themes, and levels of psychopathy. For example, exclusive child molesters were significantly more likely to receive a paraphilia diagnosis, were more likely to report having sexual fantasies, and had lower Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R) scores than other offender types. -

Mindfulness in Sexual Activity, Sexual Satisfaction and Erotic Fantasies in a Non-Clinical Sample

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Mindfulness in Sexual Activity, Sexual Satisfaction and Erotic Fantasies in a Non-Clinical Sample Laura C. Sánchez-Sánchez 1 , María Fernanda Valderrama Rodríguez 2 , José Manuel García-Montes 2 , Cristina Petisco-Rodríguez 3,* and Rubén Fernández-García 4 1 Department of Evolutionary and Educational Psychology, Faculty of Science Education and Sport, University of Granada, Calle Santander, Nº 1, 52071 Melilla, Spain; [email protected] 2 Department of Psychology, University of Almería, Carretera Sacramento S/N, La Cañada de San Urbano, 04120 Almería, Spain; [email protected] (M.F.V.R.); [email protected] (J.M.G.-M.) 3 Faculty of Education, Pontifical University of Salamanca, Calle Henry Collet, 52-70, 37007 Salamanca, Spain 4 Department of Nursing, Physiotherapy and Medicine, University of Almería, Carretera Sacramento S/N, La Cañada de San Urbano, 04120 Almería, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-923125027 Abstract: The goal of this study is to better understand the relation between the practice of Mindful- ness and the sexual activity, sexual satisfaction and erotic fantasies of Spanish-speaking participants. This research focuses on the comparison between people who practice Mindfulness versus naïve people, and explores the practice of Mindfulness and its relation with the following variables about sexuality: body awareness and bodily dissociation, personal sexual satisfaction, partner and relationship-related satisfaction, -

In the Company of Men: Male Dominance and Sexual Harassment

IN THE COMPANY OF MEN The Northeastern Series on Gender, Crime, and Law edited by Claire Renzetti, St. Joseph’s University Battered Women in the Courtroom: The Power of Judicial Responses James Ptacek Divided Passions: Public Opinions on Abortion and the Death Penalty Kimberly J. Cook Emotional Trials: The Moral Dilemmas of Women Criminal Defense Attorneys Cynthia Siemsen Gender and Community Policing: Walking the Talk Susan L. Miller Harsh Punishment: International Experiences of Women’s Imprisonment edited by Sandy Cook and Susanne Davies Listening to Olivia: Violence, Poverty, and Prostitution Jody Raphael No Safe Haven: Stories of Women in Prison Lori B. Girshick Saving Bernice: Battered Women, Welfare, and Poverty Jody Raphael Understanding Domestic Homicide Neil Websdale Woman-to-Woman Sexual Violence: Does She Call It Rape? Lori B. Girshick IN THE COMPANY OF MEN Male Dominance and Sexual Harassment Edited by James E. Gruber and Phoebe Morgan Northeastern University Press Northeastern University Press Copyright by James E. Gruber and Phoebe Morgan All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data In the company of men : male dominance and sexual harassment / edited by James E. Gruber and Phoebe Morgan. p. cm. — (The Northeastern series on gender, crime, and law) --- (cl : alk. paper)— --- (pa : alk. paper) . -

Autonomy and Community in Feminist Legal Thought Susan G

Golden Gate University Law Review Volume 22 Article 2 Issue 3 Women's Law Forum January 1992 Autonomy and Community in Feminist Legal Thought Susan G. Kupfer Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/ggulrev Part of the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Susan G. Kupfer, Autonomy and Community in Feminist Legal Thought, 22 Golden Gate U. L. Rev. (1992). http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/ggulrev/vol22/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Golden Gate University Law Review by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kupfer: Feminist Legal Thought AUTONOMY AND COMMUNITY IN FEMINIST LEGAL THOUGHT SUSAN G. KUPFER* In discussing the rights of woman, we are to consider, first, what belongs to her as an individual, in a world of her own, the arbiter of her own destiny, ... on a solitary island .... The strongest reason for giving... her the most enlarged freedom of thought and action .. .is the solitude and personal responsibility of her own individual life. -Elizabeth Cady Stanton, 18921 [W]omen have always had to wrestle with the knowledge that individualism's presti gious models of authoritative subjectivity have refused female identification. Fem inism, as an ideology, took shape in the con text of the great bourgeois and democratic revolutionary tradition. It thus owes much to the male-formulated ideology of individ ualism, as it does to the special experiences of women who have been excluded from the benefits of individualism.